Africa hosts 17% of the world’s population, but as of last week accounts for only 2.1% of the world’s COVID-19 cases. COVID-19 has spread more slowly in most of Africa than in the rest of the world, due to a number of factors. For instance, Africa has a relatively young population, and apart from urban centres (approximately 45% of Africa’s population is urbanised), most people do not live in densely populated areas. However, of those who do, approximately 61.7% live in high-density slums. In addition, most of Africa’s elderly population live with family rather than in old age homes. African governments were also quick to follow World Health Organization (WHO) and Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) guidelines and closed their borders, and introduced full or partial lockdown and social distancing measures when no or only very few cases had been diagnosed.

Some 160 days since the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in Africa, the emerging pattern is one of resilience rather than collapse, chaos and conflict #C19ConflictMonitor

Tweet

The virus has now spread to 54 African countries and is growing exponentially. The Africa CDC has reported a 21% increase in new cases last week, as compared to the week before. These all-Africa figures, however, hide a large spectrum of diverse experiences. On the one hand, there are 37 African countries with fewer than 5 000 recorded cases. On the other end of the spectrum is South Africa, which accounts for approximately 50% of all COVID-19 cases in Africa and now has the fifth-highest number of people infected in the world. The spread of the virus is still increasing steadily, and the situation is likely to get worse before it gets better. ACCORD will continue to closely monitor these developments and their emerging impact on political stability and social cohesion.

Apart from South Africa and a handful of other countries, COVID-19 has not yet emerged as a public health emergency in Africa. However, for many countries on the continent, while the measures introduced to contain the virus may have mitigated the spread of the disease, the consequences of these same measures have had a significant negative impact on the livelihoods of people and the economy more generally. A sizeable portion of people in Africa depend on a daily income through informal labour or small-scale trading to support their families, and their livelihoods have been disrupted. Many others who work in the formal economy have been unable to return to work or have lost their jobs. In South Africa, for example, approximately three million people have lost their jobs during the lockdown period. COVID-19 containment measures are also impacting on food security. Together with climate change and, more recently, the disastrous locust infestation in East Africa, there has been a negative impact on food production.

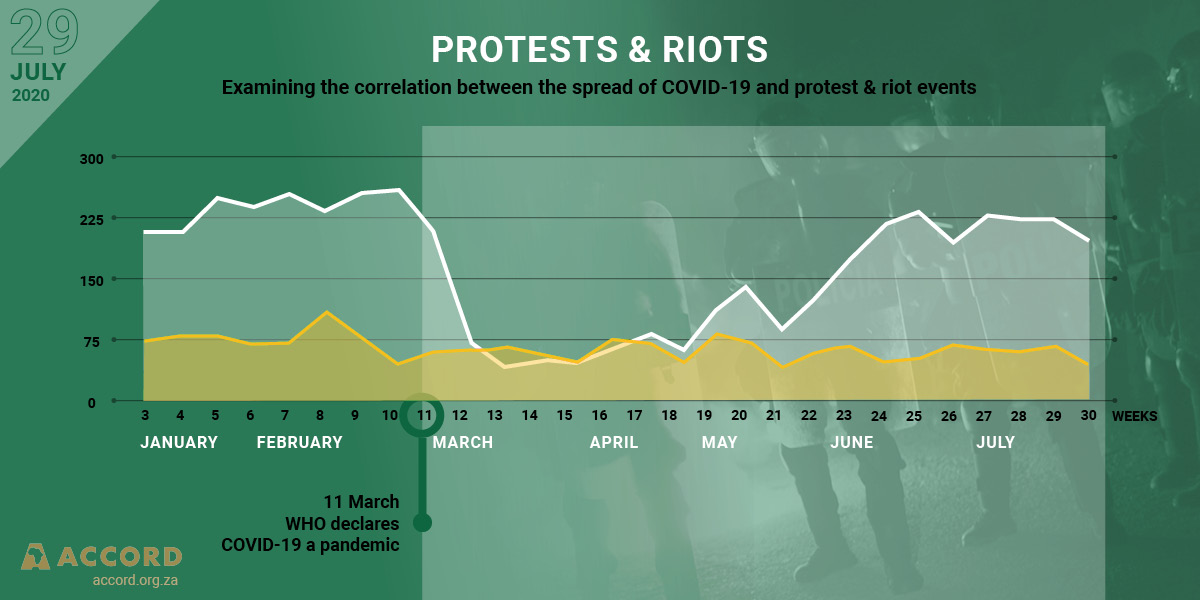

The public health emergency and related socio-economic consequences were widely anticipated to exacerbate existing vulnerabilities in societies across Africa and to contribute to an increase in social unrest and even violent conflict. We are now some 160 days into the COVID-19 crisis on the continent and these trends have not yet materialised. In fact, the lockdown measures initially resulted in a significant drop in most crimes and unrest, with domestic and gender-based violence being the exception. In the case of the latter, lockdown measures – including the closing of schools and working from home policies – have increased the risk for people who are in abusive relationships.

There has been a steady increase in public unrest as people voice their frustrations at COVID-19 containment measures and other political tensions since the first lockdown laws, but the total number of incidents has not yet reached pre-COVID-19 highs. At first, there was also an increase in arrests associated with the enforcement of the lockdown measures – which, in several cases, were enacted through emergency powers. Many countries deployed their armed forces to support the police and, in some instances, this led to the use of excessive force and other human rights abuses. In countries such as Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda, it is claimed that more people have died from security force action than from COVID-19.

The introduction of COVID-19 containment measures also posed a challenge for countries that had elections scheduled in 2020. Some postponed their elections – which, in some cases, further increased political tensions. For example, the postponement of elections in Ethiopia caused tension among opposition parties, who saw this as the ruling party “exploiting the pandemic to ensure the government’s survival”. Whilst elections went ahead in other countries, COVID-19 limited electoral campaigning and participation, which led to many of these elections being criticized.

What was also worrying was that most of the multilateral, regional and national capacities (including those in civil society) which would otherwise have been engaged in conflict prevention, mediation, peacekeeping and peacebuilding, have also been disrupted. Approximately one month into the crisis, most organisations started to adapt and develop new ways of working, but they have still been unable to do the kind of face-to-face work they were engaged in before COVID-19. At the same time, in the absence of international peacebuilders, COVID-19 has provided local peacebuilders with an opportunity to truly build and strengthen national and local capacities for peace.

Many commentators predicted that these economic and political tensions, coupled with the public health crisis, could have resulted in much more political unrest and even violent conflict than what has actually materialised over the past five months. In a few cases, stigmatisation and discrimination and heightened political tensions coupled with unrest, security force actions and deaths have been witnessed. Most countries affected by armed violent conflict before COVID-19 have not experienced a significant increase (or decrease) over the last few months. It is, of course, concerning that in such countries as the Central African Republic (CAR), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mozambique, Libya, Somalia and South Sudan, the call by the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General for a cessation of hostilities due to COVID-19 has not been followed by all the actors. However, apart from a few border tensions – mostly related to trade – Africa has not yet experienced serious interstate tensions due to, or associated with, COVID-19.

The pattern emerging out of most of Africa is one of resilience rather than conflict, due to communities and neighbours rendering support to each other; an increase in social cooperation and support provided by community organisations, women’s groups, youth organisations, faith-based organisations, the private sector and international partners; and formal relief packages in the form of social grants, tax relief, free services, etc. People, families and communities have found ways of adapting, and instead of turning to violence or other negative coping mechanisms, as many predicted, have found new ways of cooperation and mutual support in the spirit of African solidarity.

The way in which some governments, state institutions, the private sector and civil society organisations have responded to COVID-19 has built public trust and bolstered social resilience. That said, some actions have undermined trust and weakened resilience. From what we have seen over the past 15 weeks in the COVID-19 Conflict & Resilience Monitor, heavy-handed enforcement of COVID-19 containment measures and countrywide lockdown measures that don’t take into account local risk factors and the socio-economic needs of specific communities, have damaged trust and resilience. On the other hand, measures aimed at easing the impact of the containment measures – such as free services; tax relief; economic stimulus initiatives for small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs); and other social protection measures – have boosted public trust and resilience. Transparency, consultation with key stakeholders (for instance, in the corporate and education sectors) and good communication have also played important roles.

In the short term, the challenge that African civil society and governments now face is how to further strengthen and support this pattern of resilience that is emerging, in order to mitigate against the negative impact of the virus on the livelihoods of those most vulnerable, on the economy and on social cohesion more generally. In the medium term, the question is how we can use these emerging lessons in resilience to transform the way we think and organise our societies, especially when it comes to gender inequality and the role of women and the youth, our politics, our economy and our relationship with the world, including what we value in our regional and international organisations.

The ACCORD COVID-19 Conflict & Resilience Monitor editorial team: Cedric de Coning, chief editor; Senzwesihle Ngubane, Monitor manager; Marisha Ramdeen, senior programme officer and Martin Rupiya, innovation and training manager.