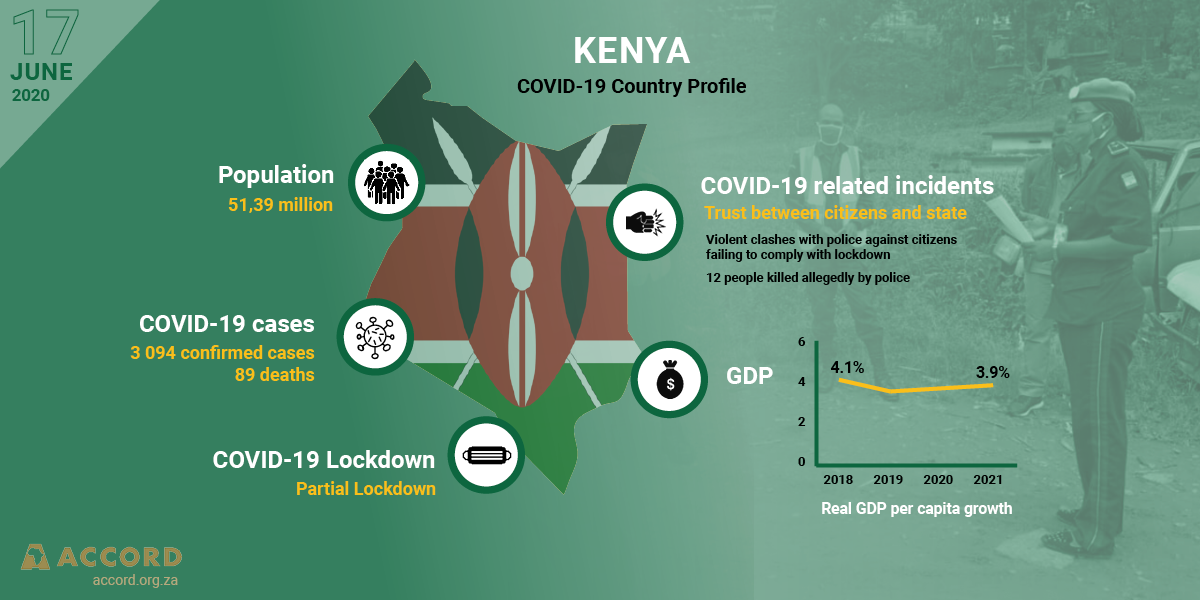

The Government of Kenya enforced a dusk-to-dawn curfew, suspended international flights and restricted movements in and out of Nairobi, Mombasa and Mandera counties, which have the highest COVID-19 cases in Kenya as of mid-June 2020. The Kenyan government is moving fast – not only to impose measures to break the chain of infection but also to ensure preparedness in the health system.

In Kenya, financial hardship due to restrictions on movement and the curfew have affected the livelihoods of many, especially those working in the informal sector. If left unaddressed, this could be a tinder box waiting to be lit.

Tweet

To ensure that the health system is not overwhelmed by the surge in the number of cases (3 826 reported cases and 104 deaths as of 15 June), the government has allocated KES5 billion to ensure that every county has a 300-bed capacity isolation centre. Furthermore, over 11 000 healthcare workers have been trained to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, with the government setting aside more funds to hire about 6 000 medics as a way of increasing capacity to fight the pandemic. While the government continues to impose various measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, citizens are expressing fear and anxiety as a result of a lack of financial security.

The economic impact of COVID-19 on livelihoods

In as much as the government has put in place strict measures to control the spread of COVID-19, citizens’ livelihoods have been adversely affected, raising existential concerns. Some of the enforced measures have led to the complete collapse of a number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMMEs), subsequently leading to significant job losses, worsening poverty and suffering. According to the Ministry of Labour, over 1 million Kenyans have lost their jobs or have been put on unpaid leave, including employees of companies such as Kenya Airways, Kenya Ports Authority (KPA), The Standard Gauge Railway, private schools, in the tourism and horticultural sectors as well as in the manufacturing industry, among others. The ministry estimates that over 2 million Kenyans will have lost their jobs by the end of June 2020. Most affected are Kenyans in the informal sector, which accounts for over 80% of employment in the country, with the majority relying on a daily income.

The government came up with economic relief packages and tax deductions, reducing value-added tax (VAT) from 16% to 14% and providing tax relief to people earning less than KES24 000 (USD240). However, the government’s economic relief packages have not trickled down to the majority of the population who have been affected by the pandemic. Many have resorted to taking loans, attempting private businesses, creating jobs online or taking early retirement. Also, with the livelihoods of many threatened, there is the possibility of increased crime in major cities, further threating peace and security in the country.

To illustrate the above challenge, Adam Burke points out that COVID-19 is already beginning to expose the fractures, prejudices and weaknesses of many marginal or conflict-affected populations. Discrimination against ethnic and racial minority groups has intensified as the virus continues to spread in Kenya. For example, there have been reports of Chinese nationals being blamed for importing the virus into the country, while the Somali population in the Eastleigh suburb of Nairobi have been accused of spreading the virus. Residents of Mombasa and Nairobi travelling to other counties for essential services have also been singled out by residents of these counties, expressing fears that the former may spread the virus locally.

COVID-19 has also seen a rise in human rights abuses. For example, since 27 March 2020, the Kenya Police Service has had the mandate of enforcing the government’s dusk-to-dawn curfew. Subsequently, videos have surfaced on social media showing police officers beating civilians on the streets as they enforced the curfew, with some of these incidents reportedly resulting in deaths. On 8 June, a group of activists, joined by a crowd of about 200 people, marched peacefully to the parliament buildings, protesting incidences of police brutality. According to the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA), 15 people have been killed by police and 31 injured since the curfew was imposed. There have also been numerous arrests of those violating curfew rules. For the poorest in the country whose livelihoods are threatened by the virus, it is counterproductive to mete out excessive force on them to effect the curfew. If anything, it increases the chances of fear and frustration, which could lead to social unrest. The president has publicly apologised to the public about police brutality against citizens during the curfew hours and promised to investigate the matter. Accordingly, police abuse during curfew hours has reduced. There have been brief incidences of social unrest in the Eastleigh area of Nairobi when a localised lockdown was imposed, but calm was quickly restored and the area has since been opened after 28 days of lockdown.

Cases of domestic and sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), especially against women and children, have also been on the rise. According to a report by UNICEF, one third of the crimes reported in Kenya since the arrival of COVID-19 have been linked to sexual violence. According to the Chief Justice of Kenya, Hon. David Maraga, the number of SGBV cases had increased by 35.8% by 20 March 2020. As an example, according to Gender Violence Recovery Centre (GVRC), a charitable trust of the Nairobi Women’s Hospital, there were 363 new SGBV reported cases in March alone, up from 290 in January, making the situation rather worrying. Gaps in SGBV response and prevention had already been key concerns for peacebuilders in Kenya prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it has exacerbated this social problem and exposed the extent to which it is prevalent.

In conclusion, financial hardship due to restrictions on movement and the curfew have affected the livelihoods of many, especially those working in the informal sector. If left unaddressed, this could be a tinder box waiting to be lit – especially for Nairobi, which is still under lockdown. So far, many poor Kenyans have found ways of surviving through small businesses and loans, but the situation is dire. The government has also eased the curfew hours to start at 9pm instead of 7pm, allowing people to work a little longer to support their livelihoods.

Elias Opongo is the director of the Centre for Research, Training and Publication (CRTPT) at Hekima University College, Nairobi. He is a peace practitioner and conflict analyst, and teaches and researches on ethics of war and peacebuilding, statebuilding and democracy, transitional justice and conflict resolution. He holds a PhD in Peace Studies from University of Bradford, UK.