Madagascar was thrown into political crisis in 2009 by an unconstitutional change in leadership which replaced Marc Ravalomanana with Andry Rajoelina as head of state. Over the past four years this crisis deteriorated into a firmly-imbedded political impasse. This stalemate seemed to have eased slightly when both Ravalomanana and Rajoelina declared, in December 2012 and January 2013 respectively, that they would not stand in the May 2013 elections.2 Notwithstanding these pronouncements, however, speculation and uncertainty still persist around the implications of these statements on efforts to resolve the political impasse and whether the country will be able to finally move forward. This Policy & Practice Brief examines two key issues impeding the peace process in Madagascar: the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Roadmap, an agreement initiated and signed in September 2011 by SADC to lay the road to peace in Madagascar, and the question of elections. It discusses the implications of the recent announcements made by the two protagonists on efforts to break the impasse and provides recommendations to support Madagascar’s progress towards long-term peace and stability.

Introduction

On 17 March 2009, Marc Ravalomanana, then president of Madagascar, handed power to the highest-ranking officer in the armed forces, asking that a military directorate be set up to rule the country. The military promptly handed over the office to Andry Rajoelina, who was at that time the mayor of Antananarivo. Rajoelina had led a series of opposition protests in the capital which had culminated in Ravalomanana stepping down from office. The transfer of power was condemned by the international community as a coup d’état, as there were no provisions in the Constitution of Madagascar for an elected president to hand over power to the military, nor for the military to transfer power to a non-elected civilian. The international community thus deemed the transfer of power an illegal seizure of government by Rajoelina. Notwithstanding this, Rajoelina, acting as president, issued an arrest warrant for Ravalomanana, who then fled into self-imposed exile in South Africa.

The tensions between Ravalomanana and Rajoelina began in 2008 when Ravalomanana’s government allegedly delayed the disbursal of funds for various local government infrastructure projects in the capital, diverted investment away from the city, and in various other ways refused to facilitate cooperation between the central and municipal governments. Rajoelina’s supporters claim these efforts were intended to undermine the mayor.3 Tensions between the two politicians deepened when Ravalomanana’s government closed Viva TV, a television station owned by Rajoelina, after it aired an interview with former President Didier Ratsiraka. The government asserted that airing the interview threatened public order and security, while critics viewed the move as a sign of increasing intolerance by the Ravalomanana government of opposition-friendly media, and an effort to curtail Rajoelina’s influence. Following the closure of the television station, Rajoelina issued an ultimatum, demanding, in the interest of press freedom and democracy, that the government allow the reopening of Viva TV and other stations by 13 January 2009.4 This demand was not met and in mid-January Rajoelina initiated what grew into a wave of public anti-government demonstrations by Antananarivo residents. Rajoelina labelled Ravalomanana a dictator and called for him to leave office – which he ultimately did in March 2009.

Rajoelina and his allies established a High Transitional Authority (HTA), which became the de facto government, as well as a Military Council for National Defence (MCND) to accommodate the higher-ranking generals. On 18 March 2009, Madagascar’s High Constitutional Court officially recognised and confirmed Rajoelina as president. Rajoelina, at 34 years of age, took power with no clear agenda, no domestic or international policies, and with no way of disassembling Ravalomanana’s deep-rooted networks in Madagascar’s political, economic and religious circles. Madagascar was soon suspended from the African Union (AU)5 and SADC,6 while most of the international community refused to recognise its government.

In June 2009, a national court sentenced Ravalomanana, in absentia, to life imprisonment for giving the order that resulted in the killing of 31 protestors earlier in the year, and for his alleged abuse of office. SADC members convened an extraordinary summit later that month and nominated the former president of Mozambique, Joaquim Chissano, to lead a mediation team to Madagascar. In early August, Chissano, along with representatives of the AU, United Nations (UN) and Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), convened talks between Rajoelina, Ravalomanana, and two former Malagasy presidents, Albert Zafy and Didier Ratsiraka, in Mozambique’s capital, Maputo. A power-sharing deal was signed on 9 August 2009 between the political leaders. Key highlights of the agreement were that the principals were to have the same powers in the administration of the country, the cabinet posts were to be shared equally among the four parties in the negotiation process and Ravalomanana could return to the country unconditionally.7 This deal was short-lived, failing when Rajoelina unanimously filled all the positions in the administration with members of his own party – leaving no room for the involvement of Ravalomanana, Zafy or Ratsiraka. This deal was followed by a second and third round of talks, in Maputo and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where it was agreed that Rajoelina would remain president of the HTA, with two co-presidents and a consensus prime minister. However, despite protracted negotiations, the parties failed to agree on key cabinet posts for the transitional government, which led Rajoelina to announce in December 2009 that he was unilaterally dismissing the Maputo and Addis Ababa agreements.8

On 17 November 2010, a referendum on a new constitution was held. The official results released by the HTA were that 73% of voters were in favour of the state’s fourth constitution. Despite the political opposition and international community complaining about numerous irregularities in the process, the constitution was approved. The one major change in the document was that the age for eligibility to stand for election as president was lowered from 40 years to 35 years, allowing 38-year-old Rajoelina to stand in any upcoming elections.9

The mediation process continued into 2011, when a fourth agreement was signed on 17 September. This agreement was known as the SADC Roadmap. The previous three agreements had been largely criticised for the inclusion of the former presidents who had been rejected by the people, either through the ballot box or popular uprisings. The agreements were said to be devoid of citizens’ input and did not take into consideration the wishes, needs and aspirations of the Malagasy people. Therefore, the Roadmap was instigated without consultation with Zafy and Ratsiraka, although it did include the participation of civil society organisations in Madagascar. The Roadmap was seen as a step in the right direction for the country as it outlined the necessary steps to peace and pledged the smooth passage of the current transitional period. However, seventeen months after signing of the Roadmap, Madagascar was still at a complete standstill in terms of moving towards peace.

The SADC Roadmap: Ravalomanana’s return and the 2013 general elections

The SADC Roadmap replaced the previous three agreements and was seen as laying the foundation for a move towards elections and political stability in Madagascar. As a consequence of the Roadmap there have been several positive results achieved towards this end. These include the creation of the Transitional Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI-T) which established a timeline for elections in the country and provided for the appointment of the prime minister of consensus, Jean Omer Beriziky, and the creation of several transitional institutions in the government, including the Transitional Parliament which is comprised of the National Assembly and the Senate.

The Roadmap, however, has also created several challenges for the peace process in Madagascar. The main ones relate to Ravalomanana’s return to Madagascar and the issue of elections. The urgent need for elections is the one point which all the political stakeholders in Madagascar can agree upon, but the task of holding these elections is regarded as an almost impossible one. Any elections held should not be rushed and must be free, fair and legitimate in the eyes of citizens and the international community. The Roadmap provides some guidance in this regard. In articles 10 through to 14, it clearly outlines that a CENI-T should be established and take on the role of preparing the country for elections and conducting them. A CENI-T was established on 12 March 2012. It is comprised of 10 civil society organisations, nine political parties and two administrators and is headed by Béatrice Atallah. On 28 March 2012, the CENI-T was given 60 days to set an election date. The next day the body established an electoral calendar or a ‘plan of action’ which outlined five steps to be completed by 11 November 2012, including revising the electoral register, providing voter education and confirming funding for the election. The plan did not, however, set a date for the vote.

The Roadmap also stipulates that the CENI-T and the UN should work together in planning the elections. However, according to a report published by Charles T. Call of the International Peace Institute, ‘the UN’s role became diminished politically after the breakdown of talks, although it continued to play a role bridging the Malagasy parties and SADC after the Maputo Agreement fell apart’.10 In May 2012, the UN released a report recommending that, in the opinion of the UN, the country should delay elections until 2013, in order to prepare fully.11 Until the July 2012 negotiations in Seychelles, the head of the CENI-T, Béatrice Atallah, was firmly advocating that it was ‘technically possible to hold elections in December this year’.12 However, the CENI-T announced on 1 August 2012 that the first round of general elections would be held in May 2013. This decision illustrates a commitment by the CENI-T to meet some of the UN’s recommendations. In late September 2012, President Rajoelina called on the UN General Assembly to support Madagascar during its time of transition, showing the leadership’s understanding that it is vital to have UN cooperation in order to have successful, internationally recognised elections in the country. The role played by the UN in the electoral process could still prove to be a contentious one, mainly in relation to funding and the certification of the results. The UN has earmarked US$35 million to support the elections – provided that the HTA agrees to the UN providing technical assistance in finalising the electoral register, as well as to other steps that guarantee a free, fair and transparent electoral process.13

The Roadmap, however, does not specify who can and cannot stand in the elections. SADC’s position was that neither Ravalomanana nor Rajoelina should stand in the elections in order to decrease the potential of a contentious result which could lead to further political instability. The two other options available were that, firstly, in addition to Ravalomanana and Rajoelina not being allowed to run, neither of the former presidents, Dieder Zafy and Albert Ratsiraka, should be able to run, as having these two participate would further increase chances of an unaccepted outcome and a recurrence of unrest. A second possibility was that all four be free to stand in the elections, because restricting participation could further increase the chance of more political instability and protests from supporters. Until December 2012, no agreement over this issue had been reached. However, on 10 December 2012, Ravalomanana made a surprise announcement that he would not be contesting in the 2013 elections. This was followed by an announcement from Rajoelina in January 2013 that he too would not contest. Although encouraging, these announcements only provide a small amount of relief to a very complicated situation. They do not guarantee that peaceful and legitimate elections will take place in 2013, nor do they shed light on who will actually stand in these elections now. In order to increase the likelihood of peaceful elections, Ravalomanana has agreed to only return to Madagascar after the vote. However, it is unknown if his supporters on the ground will accept the outcome of the elections.

Ravalomanana’s decision not to contest in the vote does not mean, however, that he has been granted amnesty as per the Amnesty Law (Article 20) in the SADC Roadmap. The Amnesty Law stipulates that all Malagasy citizens in exile can return to Madagascar ‘without condition’. However, Article 45 of the Roadmap specifies that Article 20 is to be read alongside the appendix explanatory note, in which SADC provides that it cannot support impunity and thus all convictions under Malagasy law still stand. The explanatory note on Article 20, which aimed to provide an interpretation of the term ‘unconditionally’, was introduced later by the SADC Troika Organ on Politics, Defence and Security (comprised of South Africa, Mozambique and Zambia) at the insistence of Rajoelina’s government, which refused to sign the Roadmap unless it was included. Effectively, Rajoelina and his supporters were not prepared to sign a Roadmap enabling Ravalomanana’s return to Madagascar without the explanatory note. Thus the only way to have the Roadmap ratified by all necessary parties was to include it.14 The implication of the note is that if Ravalomanana was to return to Madagascar, he would be imprisoned immediately as per the sentence meted out in the 2009 trial. Furthermore, according to Article 4 of the Madagascar electoral code, a person convicted of a crime is stripped of his or her right to vote. The connotations of this article are that Ravalomanana can neither take part, nor vote, in any election held in Madagascar, given the guilty verdict he received in the 2009 trial. In order for Ravalomanana to return to Madagascar, the amnesty must be awarded in full, as per the provisions of the Roadmap. Since Ravalomanana made the announcement independently and declared that this was not the ‘nil-nil option’ SADC proposed, there are complications regarding the issue of amnesty. The nil-nil option suggests that neither Ravalomanana nor Rajoelina should stand for election. Even with Rajoelina’s recent announcement that he too will not stand in the election, it is unclear if the full nil-nil option will be used. If it is employed in full, Ravalomanana would be able to return to Madagascar, receive amnesty for his crimes and avoid facing a new trial or jail time. Furthermore, he would not have to pay the remaining taxes he owes to the country and could continue with his business interests. However, at the time of writing, it was unclear if this would take place. Without amnesty it was highly unlikely that Ravalomanana would return to Madagascar.

Another complication around Ravalomanana’s return is the issue of his unpaid taxes. Madagascar’s electoral code stipulates that all candidates must be resident in Madagascar for the six months leading up to an election, and must have paid all taxes of any kind in the preceding three years.15 Although business operations were halted four years ago when he left Madagascar, Ravalomanana’s agribusiness company, Tiko, still owes approximately US$100 million in unpaid taxes.16 However, Ravalomanana has raised questions over why he should pay these taxes when he has not been able to operate his business since he left the country.17 Although this issue had previously added to the complications around holding credible elections in Madagascar, it is less of a concern considering Ravalomanana’s announcement that he would not contest in the election. However, it does raise issues over his ability to return to the country. It increasingly appears that the only viable option that would allow Ravalomanana to return would be for him to agree to pay his taxes. However, the presence of Article 45 in the Roadmap still means that he would be imprisoned on arrival in Madagascar, whether his taxes are paid or not. The only saving grace would be if the trial was declared illegitimate. This is possible because Malagasy law dictates that a president can only be convicted by a court in Madagascar which must be specially convened for the trial. This court, however, was not in place in Madagascar when Ravalomanana was convicted and thus, he argues, the conviction was unlawful. Furthermore, Ravalomanana was charged in abstentia without his lawyer being present, further throwing the legitimacy of his trial into question. Even if Ravalomanana’s trial was declared illegitimate and the conviction thrown out, it is unknown what implications his announcement to stand down from contesting in the elections will have on the taxes he owes. If he returns to Madagascar and is granted amnesty for the crimes committed in January 2009, this does not apply to the taxes he owes and a case could still be launched against him for tax evasion, which the Amnesty Law does not cover. Thus the recent announcement does not make it any easier for Ravalomanana to return to the country.

A final concern is around the sanctions and funding for the elections. Sanctions were imposed on Madagascar in 2010 after the coup. Articles 41 and 42 of the Roadmap refer to sanctions and international financial assistance, recommending that the sanctions be lifted based on the achievement of the milestones outlined in the Roadmap. The Malagasy economy is declining at a rapid rate and the lifting of sanctions and resumption of financial aid would be highly beneficial to the population. However, sanctions will not be lifted until the Roadmap has been adhered to, when elections are held and Ravalomanana is able to return to the country. Yet, in order to hold the elections, funding is needed. The European Union (EU) originally stipulated that it would only fund the elections once the recommendations of the UN had been met and a date, in 2013, had been set. The CENI-T responded that the rest of the electoral calendar could not be completed without the necessary funding promised by the EU. In light of the announcement by the CENI-T that elections would be held in 2013, the issue of funding should be taken up again, because the initial decision to hold the elections in May 2013 is in line with the UN’s recommendations and shows that the CENI-T is willing to work with the international community. In February 2013, however, the CENI-T announced that presidential elections, which were scheduled for 8 May, would be moved to 24 July due to operational difficulties. As yet, the EU has not released any funds and the international community has not lifted sanctions. Without the funding from the EU it is unlikely that the elections will take place, and without elections taking place it is unlikely that the sanctions will be lifted. In order to support Madagascar in its bid to hold elections in 2013, SADC has pledged US$10 million to the election process and encouraged other member states to provide financial and logistical assistance to ensure a peaceful vote.

The fact that holding elections is seen as imperative by all parties involved in Madagascar is a positive move towards transforming the conflict. Nonetheless, the complexities behind instigating these elections are a major factor in the political stalemate in the country. It is encouraging that both sides are beginning to demonstrate their recognition of the importance of the vote for Madagascar. The EU plays a central role in this process due to the pledge of funding, the UN works closely with the CENI-T to legitimise the elections and SADC plays a key role in ensuring that the Roadmap is fully implemented. Even with a date set and the recent announcements, there is no assurance that this timeline will be followed through by the relevant parties, and that the elections will take place. There is also no guarantee that holding elections will address the root causes of the political instability and socio-economic decline in the country. This is where international pressure is vital. Now that a date for the elections has been set, the international community and relevant stakeholders need to ensure that this timeline is adhered to in order to ensure that legitimate elections take place, a government is chosen by the people and is instituted in the country, and that issues plaguing the nation are addressed. Otherwise the present political instability will continue.

International involvement in Madagascar: What can be done to end the impasse?

The Southern Africa Development Community

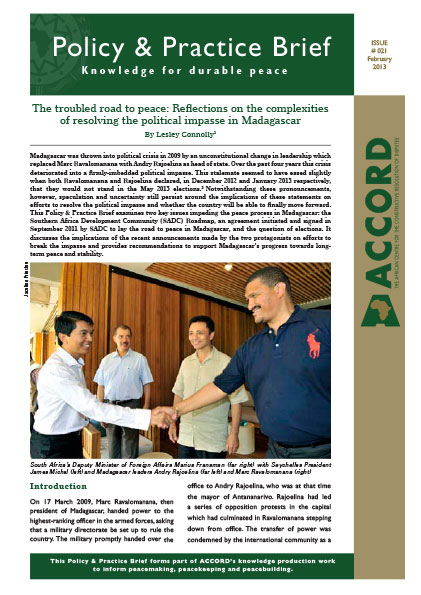

SADC has been involved in the negotiation process in Madagascar from the onset. The aim of the regional body has been to ‘bring about a solution to the crisis in Madagascar and return the country to constitutional normalcy’.18 Towards this end, SADC established a SADC Mission in Madagascar in 2012, initiated the Maputo I Peace Accord and has made efforts to remain involved in all subsequent negotiations. SADC’s engagement was strengthened by the fact that South Africa was the head of the SADC Troika Organ on Politics, Defence and Security while simultaneously hosting Ravalomanana in exile. SADC held two rounds of negotiations in Seychelles in July and August 2012 with Ravalomanana and Rajoelina, as a last attempt to reach an agreement before the SADC Summit in Maputo in late August 2012. It was announced, after these meetings, that both protagonists were committed to moving Madagascar towards a stable future,19 but that agreement on Ravalomanana’s return and who was able to run in the elections had still not been reached.

Thus far, SADC’s role has not been viewed very positively by all the parties involved in Madagascar, because of the perception that the body is pro-Ravalomanana. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, it was only in 2004 under Ravalomanana’s leadership that Madagascar became a member of SADC. Secondly, there is a view that because South Africa is hosting Ravalomanana, the organisation is pro-Ravalomanana, which has the consequence of discrediting the mediators in the eyes of both Rajoelina supporters and the current government. These two issues make it hard for SADC to conduct negotiations between the two sides, thus adding to the current impasse in the country. Furthermore, there is tension between the Francophone and Anglophone influences in Madagascar, and SADC is caught in the middle. Being a Southern Africa-based body, it is viewed as having less French influence, and more Anglo-backing, which adds to the already difficult hurdles that SADC has to tackle.

It is vital for SADC to resolve this conflict, even if it is simply through a short-term political agreement to allow elections to take place. South Africa would have liked Ravalomanana to return to Madagascar before the Troika headship was transferred to Tanzania at the August 2012 SADC Summit. This did not happen. At the summit, no decision was taken about who would stand in the elections. However, SADC did endorse the electoral calendar produced by the CENI-T and asked the transitional institutions to assist in resolving the impasse. At the December 2012 SADC Summit held in Tanzania, SADC reiterated its stance that both Ravalomanana and Rajoelina should not stand in the elections, Ravalomanana should be allowed to return unconditionally to Madagascar, and the Amnesty Law should be applied to the former leader.

Following the Summit, Ravalomanana announced his decision not to contest in the election. This was followed by Rajoelina’s own announcement, after a private meeting with SADC in January 2013, that he too would not stand in the election. These pronouncements, however, do not mean that SADC’s role is over. It is crucial now for SADC to maintain its engagement in the process of establishing stability in the country.This brief recommends that SADC continues its engagement with civil society and religious organisations, particularly the National Coalition of Civil Society Organisations (CNOSC) and the Group of Christian Churches in Madagascar (FFKM) as specified in the SADC Roadmap, in an attempt to move the country towards successful elections and the return of Ravalomanana. In addition, this brief recommends that SADC works with these local organisations to ensure that the reconciliation process begins and that the root causes of the conflict are addressed in order to increase the likelihood of long-term peace and development in the country.

The African Union

Due to past trends of unconstitutional changes of power in African countries, the AU took a very strong stance on Madagascar, condemning the coup d’état in attempts to prevent the legitimisation of leaders and governments who came into power this way. The AU suspended Madagascar from the body immediately after the coup, and a year later imposed a travel ban and diplomatic isolation on the government.20 The AU led the first three mediation processes, but has since allowed SADC to take over leadership of the negotiations and monitoring of the situation in the country. Despite stepping back, the AU was still offering full support to SADC and applying pressure on Madagascar to reform. The AU’s continued application of this pressure in terms of sanctions and withholding of membership was invaluable in adding to the international pressure on the country to change and elect a legitimate leader. This brief commends the AU for upholding its stance of not recognising leaders who come to power via coups. It is now, however, imperative for the AU to increase its advocacy among its member states to provide logistical and financial support to Madagascar. The continental body also needs to continue to support the SADC-led initiative in Madagascar in order to ensure that the country is able to hold free and fair elections and encourage a smooth transition to peace and stability.

The United Nations

The UN has been involved in the mediation process in Madagascar since the beginning of the crisis in 2009. UN Assistant Secretary-General for Political Affairs, Haile Menkerios, and UN Senior Adviser, Tiébilé Dramé, have been working with SADC and the AU. They have been strong advocates for inclusive talks as the only way out of the crisis. The UN led a field research mission to Madagascar in 2012 to evaluate concerns and progress made.21 Its report outlined recommendations for moving the country forward, including holding elections in 2013. The UN did meet with Rajoelina to encourage reform. However, it was important to make clear to Rajoelina that despite the meetings with the UN, the international community still did not recognise him as a legitimate head of state, and that elections had to take place to decide the future of the country. The UN is encouraged to maintain this policy and to continue to push for elections to take place in 2013 so that a legitimately elected president can lead the country to stability. The UN can also play an important role in encouraging member states to provide logistical and/or financial support to the country and to send independent election monitoring teams to observe the vote and provide a measure of legitimacy to this important process.

The European Union

The EU has suspended economic and humanitarian aid to Madagascar. However, the supra-regional body has remained silent about France’s continued support of the HTA.22 The EU plays an important role in terms of the elections because the body has pledged to fund them, but only if the CENI-T works with the UN and the elections are held in 2013. This brief recommends that the EU maintains this position, despite the pressure France may bring to bear against this, thus ensuring that Madagascar follows international recommendations, holds the elections in 2013, and cooperates with the UN. The simple reality is that the elections cannot take place without this funding and thus the EU holds much bargaining power in the situation.

France

France is a major player in Madagascar’s state of affairs and the country’s power and interest should not be disregarded. Madagascar, as a former French colony, is of strategic economic value to France, because of its location, minerals and other natural resources.23 When the crisis started in March 2009, France was viewed as supporting Rajoelina via the provision of financial assistance disguised as humanitarian aid, this despite the fact that the EU had suspended support to the country. This support for Rajoelina continued between 2009 and 2012.24 France’s backing of Rajoelina may also have been influenced by the fact that Ravalomanana expelled the French ambassador from Madagascar, which was the first time such an action had occurred. In addition, in August 2005 Madagascar for the first time joined SADC, which some took as indication of an intention by Ravalomanana to move away from the traditional French post-colonial influence. He was also seen as moving closer to the United States and opening up the country to Chinese and South Korean interests. These moves have been interpreted by some as the reason behind the increased tensions between Ravalomanana and France.25 However, it is difficult to know the extent to which France is involved in the conflict at present. One must take into consideration that towards the end of 2012, France transitioned from a conservative to socialist government, which could have implications for Madagascar. At the time of writing, it was unknown what stance President Hollande would take with regard to Madagascar. What was known was that, above all, the French would want to ensure stability and prevent any slide towards civil conflict, thus protecting their extensive economic and political interests.26 Thus, due to the interest and influence France has on Madagascar, this brief highlights the urgent need for actors involved in resolving the political crisis in Madagascar to work with and accommodate French interests during the process of political bargaining and reflection on the architecture of the political agreements.

Conclusion

The recent announcements by both Ravalomanana and Rajoelina that they would not contest in the 2013 elections has altered the nature of the crisis in Madagascar, without resolving the political impasse. It is still unknown whether Ravalomanana can return to Madagascar, whether he will receive amnesty, and the outcome of the case of outstanding taxes he owes the country. Furthermore, it is unknown who will now contest in the elections, the likelihood of the result being accepted by the Malagasy people, and where the funding for these elections will come from. It would seem that the path to the elections is no clearer now than it was before the announcements. Developments over the months preceding the elections are key to resolving the firmly entrenched political impasse. It is clear to both actors, and the international community, that it is imperative to end the crisis. The situation is deteriorating socio-economically and it is becoming increasingly important to bring some political stability to Madagascar in order to begin the process of rehabilitating the economy and improving the lives of the Malagasy people.

In order to overcome the impasse, one needs to consider all the issues at hand and see if a compromise can be reached. One also needs to consider the potential for future violence in the country, and how to lessen the chances of social unrest. The dynamics of the social situation on the ground are unknown, and it is hard to grasp how much support each protagonist has. Thus, the potential for violence, both pre- or post-elections, is difficult to predict. As Zartman27 points out, the key players in a mediation process have a lot of influence over what can happen, and SADC and other international actors need to utilise this power and continue to exert pressure to move the protagonists towards an agreement. However, it seems inevitable that whatever agreement is reached will only achieve a temporary peace. One cannot overlook the history of instability in Madagascar, which typically starts with public strife, which a ‘new’ leader then uses to create instability and which ultimately results in the overthrow of the existing government. This is what has happened with Ravalomanana and Rajoelina, and similarly during Ratsiraka’s and Zafy’s tenures in government. It is a curious pattern which needs to be addressed if one is to break the cycle and establish sustainable peace and stability in Madagascar.

Endnotes

- The author acknowledges the contributions of Dr Grace Maina and Senzo Ngubane towards the development of this brief. She is grateful for their invaluable comments, insights, reviews and critiques.

- South African Press Association-Agence France Presse. 2012. Ravalomanana won’t contest polls. News24.com, 12 December. Available from: <http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Ravalomanana-wont-contest-polls-20121212> [Accessed 11 January 2013]; South African Press Association-Agence France Presse. 2013. Madagascar: Rajoelina will not run for president. Mail and Guardian (online), 16 January. Available from: <http://mg.co.za/article/2013-01-16-madagascar-rojoelina-will-not-run> [Accessed 16 January 2013].

- Ploch, L. and Cook, N. 2012. Madagascar’s political crisis. Congressional Research Service Report, June 18 2012. Available from: <https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R40448.pdf> [Accessed 31 July 2012].

- Ibid.

- Powell, A. 2009. African Union suspends Madagascar. Huffington Post World, 31 March. Available from: <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/03/20/african-union-suspends-ma_n_177306.html> [Accessed 25 July 2012].

- Africa Gateway. 2009. SADC Suspends Madagascar. Africa Gateway, 31 March. Available from: <http://www.southafrica.info/africa/sadc-310309.htm> [Accessed 31 July 2012].

- Zounmenou, D. 2009. Madagascar: A triumvirate to head the transition government. Institute of Security Studies Review, 10 November. Available from: <https://www.issafrica.org/iss-today/madagascar-a-triumvirate-to-head-the-transition-government> [Accessed 20 July 2012].

- BBC World Service. 2009. Malagasy politics tops SADC agenda. BBC World Service, 20 June. Available from: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/specialreports/africa_newstimeline_june09.shtml> [Accessed 10 July 2012].

- Tendi, B-M. 2010. Madagascan referendum could deepen political crisis. The Guardian Online, 17 November. Available from: <http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/nov/17/madagascar-referendum-political-crisis > [Accessed 4 September 2012].

- Call, C. 2012. UN Mediation and the politics of transition after constitutional crises. New York, International Peace Institute. p.22.

- Madagascar Tribune. 2012. United Nations report of the electoral needs assessment mission to Madagascar, 22 April to 8 May 2012. Madagascar Tribune. Available from: <http://www.madagascar-tribune.com/IMG/pdf/Madagascar_NAM_report.pdf> [Accessed 12 August 2012].

- Alamandie. 2012. Madagascar toujours sans date de scrutinlégislatifet presidential. Alamandie, 29 May. Available from: <http://www.romandie.com/news/n/_Madagascar_toujours_sans_date_de_scrutin_legislatif_et_presidentiel52290520121828.asp> [Accessed 14 July 2012].

- Institute for Security Studies. 2012. Peace and security council report, No 40, November. Available from: <http://www.issafrica.org/uploads/Nov_12_ENG.pdf> [Accessed 12 August 2012].

- Ravalomanana, M. 2012. Call on SADC and the AU to provide effective leadership to end the political crisis in Madagascar, August 12. Available from: <http://collectif-gtt.org/file/Call_on_the_SADC_and_the_AU_to_provide_effective_leadership_end_the_political_crisis_in_Madagascar.pdf> [Accessed 5 September 2012].

- South African Press Association-Agence France-Presse. 2012. Election law could block Ravalomanana, News24, 12 July. Available from: <http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Election-law-could-block-Ravalomanana-20120711> [Accessed 15 July 2012].

- Madagascar Tribune. op cit.

- TIKO Group. 2009. Communiqué du groupe Tiko. Topmada, 8 April. Available from: <http://www.topmada.com/2009/04/communique-du-groupe-tiko/> [Accessed 12 August 2012].

- The Herald Online. 2011. Madagascar’s roadmap to peace. The Herald Online, 19 October. Available from: <http://www.herald.co.zw/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=24119:madagascars-roadmap-to-peace&catid=45:international-news&Itemid=137> [Accessed 30 June 2012].

- Khaduai, P. 2012. Madagascar: The long road to reconciliation – Madagascar’s first halting steps. AllAfrica.com, 31 July. Available from: <http://allafrica.com/stories/201207310268.html> [Accessed 1 August 2012].

- McGreal, C. 2012. African Union suspends Madagascar over ‘coup’. The Guardian, 20 March. Available from: <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/mar/20/african-union-suspends-madagascar> [Accessed 28 January 2013].

- South African Press Association-Agence France-Presse. 2011. UN warns Madagascar. News24.com, 25 September. Available from: <http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/UN-warns-Madagascar-20110925> [Accessed 28 January 2013].

- The Telegraph. 2009. Madagascar power grab denounced as coup d’etat by EU. The Telegraph, 19 March. Available from: <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/madagascar/5019402/Madagascar-power-grab-denounced-as-coup-detat-by-EU.html> [Accessed 28 January 2013].

- Cawthra, G. 2010. The role of SADC in managing political crisis and conflict: The case of Madagascar and Zimbabwe. Mozambique, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Mozambique. Available from: <http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/mosambik/07874.pdf> [Accessed 30 June 2012].

- Sixpence, P. Unpublished. Understanding the conflict in Madagascar. South Africa, ACCORD.

- Cawthra, G. op cit.

- Sixpence, P. op cit.

- Zartman, W. 2001. The timing of peace initiatives: Hurting stalemates and ripe moments. The Global Review of Ethnopolitics, 1 (1), pp.8–18.