- Policy & Practice Brief

The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Border Communities

This Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) discusses the implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on border communities, principally in relation to border controls by governments and trans-border activities by community members living close to the border in Zimbabwe.

Executive Summary

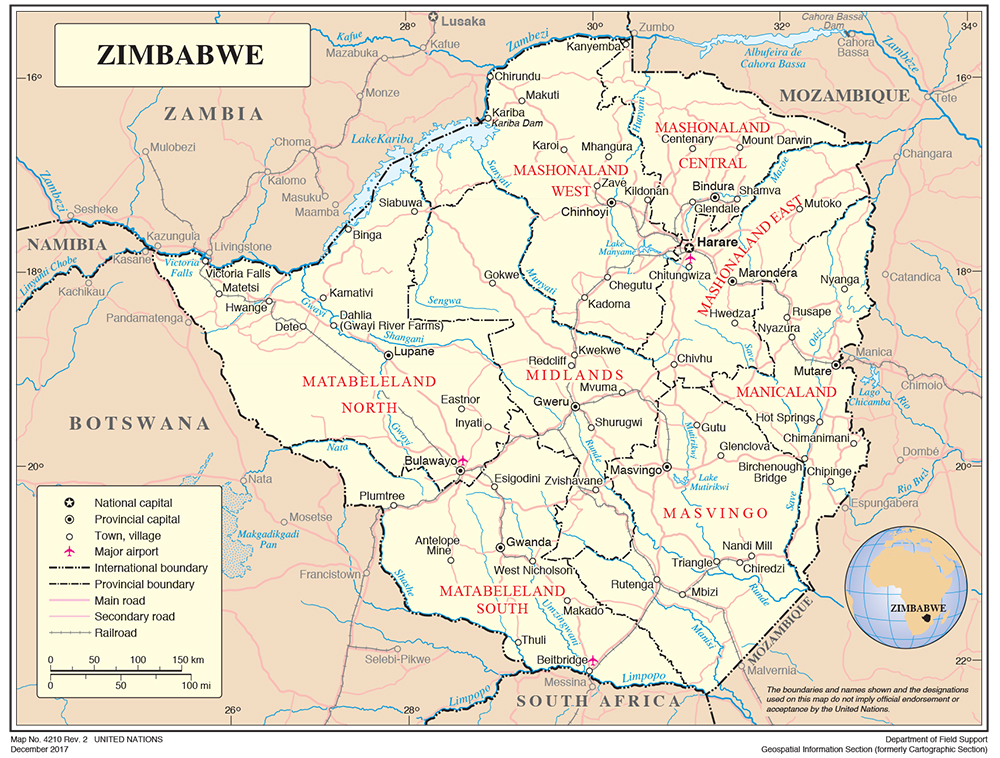

This Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) discusses the implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on border communities, principally in relation to border controls by governments and trans-border activities by community members living close to the border in Zimbabwe. This is done with a special focus on the Chipinge district to the south-east of the country, which shares the border with Mozambique. The PPB argues that the border has become the lifeline of the Chipinge communities. Therefore, with the outbreak of COVID-19, efforts to regulate the movement of people across the border have served to weaken their economic and social base, while simultaneously promoting illicit deals along the border as people try to earn a living and interact.

The brief further argues that the porous nature of the border has kept such border communities on high alert since people are increasingly using illegal entry points (bush paths), which expose them to further dangers in addition to the pandemic. This is happening amidst the lockdown instituted on 30 March 2020 in Zimbabwe and the closure of the border by the Zimbabwean and Mozambican governments. COVID-19 has increased the suffering of the communities in Chipinge. Among other problems, they are still trying to recover from the damage caused by cyclone Idai and the Mozambican Civil War, and they live in fear of earth tremors in Mozambique that often affect Chipinge. However, for some, it is still business as usual, and they are taking longer to accept the ‘new normal.’ This brief, therefore, discusses the impact of COVID-19 on some of the communities that occupy the vast area of land along the Mozambique-Zimbabwe border, from Rusitu Valley to Mahenye in Chipinge.

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has greatly affected the world, with death as its worst manifestation. It has not spared Africans, with border communities in some ways worse affected than elsewhere. The pandemic has brought a change in routine and survival strategies for communities and increased vigilance in terms of border controls. For Chipinge, this has not been the only tragedy in recent years. Some residents are still trying to come to terms with the disastrous effects of the 2019 cyclone Idai, the scare caused by recurrent earth tremors along the border with Mozambique, as well as the effects of the Mozambican Civil War on border communities in Chipinge.

The social and cultural ties that developed over the years among communities from either side of the border, lamentably, have been compromised as a result of the pandemic. Members of the border communities are now exposed to dangers, as they continue to use illegal entry points, most of which are bush paths, in order to continue with the lives they were used to before the pandemic. Criminal activities, such as the smuggling of goods, are on the rise as people try to make ends meet. This threatens the lives of the people, as there is a great danger of carrying the virus into their communities. People live in fear of contracting the deadly virus due to their proximity to the Mozambique-Zimbabwe border. This has become increasingly worrisome with cases of local transmissions on the rise in Zimbabwe.

The new requirement on the community to report border jumpers to traditional leaders and the need for traditional leaders to remain on high alert have changed the fabric of society. Some people from Mozambique have always crossed the border to Zimbabwe to provide labour on the estates along the border, and some come to conduct private trade business. This has complicated tracing and controlling those who might bring the pandemic to the community. With most of the border communities being in rural areas, little attention has been paid to the hazard that the pandemic can cause, despite the efforts being made by healthcare personnel to educate people. Social distancing, the wearing of masks, sanitising, and general hygiene have not been observed by some people, thereby exposing the communities to health risks. Some communities, such as the Tongogara Refugee Camp, are at great risk as a result of their set up.

The border

The Mozambique-Zimbabwe border, which embraces Chipinge district on one side, and Mozambican communities on the other, is a colonial establishment, like almost all borders on the African continent. While it was primarily meant to demarcate the spheres of influence of the Portuguese and the British through the 1891 Anglo-Portuguese treaty, the border has remained artificial.1 The border was intended to cut people of common origin, religion, ethnicity, language, marriage, and blood off from one another.2 The Ndau people are found on either side of the border between the two countries, and for most of them, either side of the border is home. The common Ndau language and identity has kept the people united and made movements across the borders easy, for the people are not strangers away from home. While there are restricted official ports of entry, which regulated movement as early as the colonial period, there are numerous bush paths that Africans use to cross the border and where nobody has been able to restrict their travel.3 Thus, the border has remained highly porous to this day.

Cross-border migration between Chipinge and Mozambique has long been the order of the day as people responded to economic, political and social forces in their countries. Many Mozambicans made Zimbabwe their new home during Mozambique’s civil war from 1975, when their original homes became uninhabitable. This resulted in most of them being housed as refugees at the Tongogara Refugee Camp in Chipinge, Zimbabwe, where some are still found to this day as displaced Mozambican nationals. Additionally, from colonial times, many people from Mozambique have been crossing the border into Zimbabwe, mingling with communities such as those in Chipinge, to access services at schools, clinics, and grinding mills, as well as employment in the many estates in Chipinge district. This was necessitated by low employment opportunities for Africans in Mozambique under Portuguese rule.4

The situation began to change from mid-2000, which witnessed an increased flow of people from Zimbabwe to the Mozambique side due to the economic meltdown in Zimbabwe.5 This was more common among communities such as those in Chipinge, whose people found it economical to walk to the nearest shopping centres in Mozambique, such as Maridheya, Espungabeira and Gogoi, for basic commodities.

Furthermore, the discovery of gold and diamonds in parts of Mozambique around the Chimanimani region in 2004 attracted artisanal miners, known as makorokoza, mostly from Chimanimani and Chipinge in Zimbabwe, to the goldfields in the Mt Binga area. Most of these artisanal miners have established social ties with the locals in Mozambique through marriage, kinship, and ethnicity. They are thus more readily welcomed by these communities.6 This means that migratory families have been established along the border. In the minds and lives of these communities, even today, the border does not exist at all. People move between the two countries comfortably to access various services, and for them, this is acceptable and normal.7

Cross-border movements have also been made easier as a result of there being no prohibitive physical barriers along the routes, such as large rivers, fences or insurmountable terrain. In some places along the border, the demarcations are not clearly established, to the extent that one would wonder whether one is still in Zimbabwe or Mozambique. It is mostly those who live very close to the border who are able to tell which side of the border they are on from certain features of the landscape.8 This interaction along the Chipinge-Mozambique border has created a cosmopolitan society on either side, which is only separated by a thin line on a map. What appears to be two societies, is actually one. In such border scenarios, declaring a lockdown of a country and closing its borders may not be an effective way of stopping the spread of COVID-19, as the communities remain very vulnerable. While the measures, which were mainly introduced by the Government of Zimbabwe, were adopted to safeguard public health and welfare, they have brought profound challenges for most communities in general, and border communities in particular.

The communities in Chipinge district, whose lives were and are still dependent on trans-border activities, have been greatly affected by the changes brought by the pandemic. The proximity of most of these places to the border puts them at greater risk of contracting the virus. The Chipinge border with Mozambique is dotted with communities that survive primarily through farming, but they supplement their income by trading with some communities in neighbouring Mozambique. During times of economic hardship, the border has become their lifeline. This is characteristic of communities in the most easterly part of the district, which include Rusitu, Paidamoyo, Makwaha, Ndieme, Mutsvangwa, Southdown, Tamandai, Mapungwana, Mt Selinda, Zona, Emerald, Dimire, Jersey, Gwenzi, Smalldeal, Muzite, Beaconhill, Mundanda, and some communities in the dry Savé Valley, such as Munepasi and Mahenye, among others. The current hyperinflationary environment in Zimbabwe has sent most of the people from these communities into Mozambique for basic commodities which they can no longer afford to buy in Zimbabwe. This has become the culture, with town dwellers of Chipinge not spared, since they, like many town dwellers elsewhere, struggle to maintain even a basic standard of living under the struggling economy.

The commodities most in demand from Mozambique are flour, rice, cooking oil, spaghetti, paraffin, and even fuel for vehicles. For some in the informal sector, bales of second-hand clothes are imported.9 During the summer season in Mozambique, there is an abundance of dried and fresh fish, which are commonly known in the local language as bakayawe and shereshende, respectively.10 Some locals from Chipinge carry with them items to sell in Mozambique in order to purchase the items they require.11 In the same way, communities in Mozambique along the border travel to Chipinge to buy certain basic commodities, and some come to sell items, including sweet potatoes, to locals on the Zimbabwean side in places such as Jersey and Mundanda. Others travel as far as Chipinge town for major shopping.12 Such activities, which have been prevalent over a long period of time, have established a strong cross-border socio-cultural and economic system. This has diminished the impact of the border, while at the same time allowing people to earn a living.

Photo by Gary Bembridge.

COVID-19 and the ‘new normal’

As a response to the outbreak of COVID-19, and in order to curb the sharp rise in deaths from the pandemic, many countries around the world declared lockdowns and closed their borders to foreigners. This was also the case with many African countries, with Zimbabwe and Mozambique not being exceptions. Zimbabwe closed its borders on 30 March 2020 as a move to curb the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Among other things, the lockdown ran concurrently with the closure of primary and secondary schools, as well as tertiary institutions. All non-essential local travel was restricted, and unnecessary social visits were banned. The government also suspended weddings, court hearings, and all other public gatherings.14 Similar measures were introduced in Mozambique to curb the impact of the pandemic.15

As a result of these measures, only Zimbabwean nationals could return home across the border at official points, and they would be subject to a strict 21-day quarantine period. Additionally, they were required to produce a certificate indicating that they did not have the coronavirus when coming from COVID-19 hot spots.16 These measures were intended to curb the spread of the virus through returning residents.

With COVID-19 on the scene and the borders closed and strictly monitored, crossing to the other side has become highly problematic for the communities along the Chipinge-Mozambique border. The fear of being arrested by security forces from either side of the border seems to override some people’s fear of the coronavirus. At the same time, the need to earn a living has led some to travel across the border and to ignore the fact that the virus presents a threat to their lives. There are also some people who have been misled by misconceptions about the virus, including that it affects only those living in particular areas and not those in the rural areas, where the majority of the people are living.17

The outbreak of the virus has greatly transformed the lives of some of these border communities. Trans-border activity has significantly reduced among the communities, especially through official entry points, such as the Espungabeira border post. Many have resorted to a illegally crossing the border hoping to evade the security forces from either side of the border. The bush paths, which are a traditional feature of the porous borders, have increasingly become the means to cross the border, especially for those who have failed to come to terms with the ‘new normal.’ The porous nature of the border has allowed some kind of interaction to continue between the two communities in spite of COVID-19. Some people still cross the border late at night and the early hours of the morning through the many bush paths.18 This means that some illicit deals are going on through the border despite the restrictions. Warning shots have been fired by the Zimbabwean authorities to ward off illegal smugglers of goods, especially those with bales of second-hand clothes travelling across the Mt Selinda border in Chipinge, among other border entry points.19

The estates along the border, such as Jersey, Zona, Ratelshoek and Southdown, still depend on labour from Mozambique, as they used to do during the colonial period and prior to the pandemic.20 These estates cannot do without this labour, especially considering that the work-and-learn programme, which used to assist them with labour from primary and secondary school children, is no longer operational. Under this programme, estates enrolled students in their schools, and the students would provide them with labour on the plantations as payment for their education. Since the programme stopped, labour has been obtained from local community members. This includes community members from neighbouring Mozambique who have worked on these estates for many years, and who therefore established some temporary bases around their place of work. Some have relatives that they keep in touch with across the border in Zimbabwe.21 This has produced dual homes for some people, making their movements across the border appear normal.

During the pandemic, these communities along the border have been exposed to the virus more than communities further away from the border because of the high volume of human traffic across the border. For instance, illegal gold miners circumvent those areas they know are monitored by security forces, and they are still able to reach the mining areas.22 Some artisanal miners spend weeks, if not months, in “Musanditevera”, the no man’s land around the Mozambique-Zimbabwe border, after which they return to their families in Chipinge and surrounding areas. Thus, the borders have remained ‘open’ despite the governments’ attempts to close them and the lockdowns declared by the two countries.

Our observations are that some people are crossing the border to visit their relatives, as this border separates the Ndau, a relatively homogenous group. Others are crossing the border to attend functions and ceremonies, such as funerals, since there are families living on both sides of the border. Some people from neighbouring countries, such as South Africa, do not make use of the official entry points in an effort to avoid isolation at quarantine centres in the country. These individuals use the bush paths through neighbouring Mozambique into Zimbabwe to reach their homes.23 This activity has exposed communities along the route to COVID-19. The high chance of contracting the coronavirus has also resulted in growing fear and anxiety among border communities.

With the increase in the number of local transmissions in Zimbabwe, and the difficulty in tracing them, health experts have raised concerns. They argue that most COVID-19 cases have been identified among returning residents, or they have been linked to confirmed cases.24 Health experts have also blamed the increase in local transmissions on patients with the coronavirus escaping from quarantine centres, and people entering the country illegally through porous borders.25 The Ministry of Health in Zimbabwe has reported some cases of people who died from COVID-19, but the source of infection is unknown.26 The Chipinge communities along the border are exposed to COVID-19 since there is a hive of activity in the area. This has happened amidst warnings from health experts to members of the public against harbouring border jumpers who have not been tested for the coronavirus.27

Fear for these border communities, especially with the rise of local transmissions, has resulted in some COVID-19 task forces engaging with traditional leaders to help enforce the lockdown in rural areas. They have been tasked with preventing border jumping and encouraging communities to report cases of returnees living in rural areas after entering the country illegally.28 Thus, rural communities in many parts of the country, and Chipinge in particular, have had to adjust to these new requirements. However, this is a challenge because community members may not want to report on one another to traditional leaders. This could sow seeds of distrust among community members and negatively affect the existing social fabric in rural areas.

The Tongogara Refugee Camp in Chipinge has been seriously exposed to COVID-19. This border community was created by the Government of Zimbabwe in the early 1980s to cater to displaced people as a result of civil unrest in Mozambique and other areas, such as in the Great Lakes region.29 Its close relationship with the Mozambique border, by virtue of it housing some Mozambican nationals, is a factor that must be taken into consideration. The situation for the Tongogara refugee community is very delicate considering its composition, as well as its free movement policy, which was originally put in place to assist with the integration of refugees into host communities.30 This policy allows refugees to move in and out of host communities, but as things stand, this puts them at risk of contracting the coronavirus if there happens to be an outbreak in the area.

Although measures have been put in place to isolate community members who return to the camp after visiting COVID-19 hot spots, there is still a danger of the virus being brought into the camp. Some occupants cannot resist the temptation to cross back into Mozambique to visit their relatives. The Tongogara community is also overcrowded and thus at greater risk. While the camp was designed to cater to a maximum of 3 000 people, it now houses about 14 000 people. The camp also has the largest primary and secondary schools in the country, with more than 3 600 and 2 000 students, respectively.31 The vulnerability of these people, who already face a humanitarian crisis of displacement due to wars in the region, is worrisome.

In crowded spaces like refugee camps, the potential for infectious diseases to spread rapidly is high in general, and more so for the coronavirus, as it is extremely contagious. Despite the efforts of the Ministry of Health and Child Care, together with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), it has been difficult for large communities living in such refugee camps to take precautionary measures for their safety. It is a challenge for these large groups of people to maintain social distancing. Efforts to educate people on the need to wear masks and wash their hands frequently have not always been successful. Members of the Tongogara community, as well as other concerned parties, fear the consequences of an outbreak.

However, for some, it remains business as usual, and this increases the danger, especially for border communities where there are high levels of human and other forms of traffic. Manicaland has been identified by the Government of Zimbabwe as one such high-risk zone.32 The Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) has also raised concerns over the reckless behaviour of some members of the public who continue to violate COVID-19 lockdown regulations in the country. The police have condemned some members of the public for failing to wear masks, maintain social distancing, and avoid unnecessary travel. Some people who have failed to abide by the lockdown regulations have been arrested. The police have also condemned parties taking place in people’s homes, including in some of the major urban centres, which increase the risk of spreading the coronavirus. This has resulted in the police urging people to change their attitude towards the lockdown regulations.33

While those residing in urban areas have been condemned for recklessness in the face of COVID-19, the situation is worse in rural areas. Regardless of the efforts being made by the responsible authorities to help these communities by making them aware of the dangers of the pandemic, many people still do not comply with the lockdown regulations. In rural areas, some people continue to flout the lockdown regulations, including moving about in public spaces without wearing masks, and not maintaining social distancing. Others have taken a long time to accept and begin adhering to the regulations.34 This situation is highly problematic at funerals and other gatherings where there is a very high risk of spreading the virus.

Recommendations

In order to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in borderlands such as Chipinge, the following recommendations are useful:

- Governments need to make available and increase testing centres in rural areas.

- Communities must be encouraged to abide by all existing COVID-19 protocols, such as social distancing, when attending social gatherings, including funerals.

- Local leadership structures, such as village heads, must be empowered and supported by the government to ensure communities observe existing COVID-19 protocols.

- Government must conduct frequent awareness-raising campaigns in all public places, especially ensuring that they reach the rural areas.

- Governments with shared borders must ensure full cooperation between their authorities to regulate and control the movement of people across the borders.

- Sanitisers and face masks need to be made available at no cost to the public.

- In the spirit of participatory development, organisations and government departments need to engage communities on how best they can reduce the spread of the virus. If people participate in the formulation of guidelines, the chances that they will observe the guidelines are much higher.

Conclusion

The onset of COVID-19 has had an impact on border control and trans-border activities, especially for border communities. Following the outbreak of the pandemic, governments of different countries reacted in much the same way by instituting lockdowns and the closure of borders, followed by a number of other measures. This was done to prevent the spread of the pandemic. While this had some impact generally on many communities, the border communities have been hard hit by the measures, especially those who have faced other recent tragedies, such as Chipinge.

The lockdown and the closure of the Mozambique-Zimbabwe border, firstly, created some restrictions on the communities’ activities across the border. However, trade across the border is the border communities’ lifeline, despite the negative experiences around it. With the borders closed, people have had to devise new means of making a living, but many continue to cross the border in order to survive amidst the harsh economic environment in the country. Thus, for some, crossing the border through the bush paths has remained a way to make ends meet. This resulted in some illicit deals, such as the smuggling of goods, until the government put a stop to this. The government’s call for traditional leaders to enforce the regulations in rural areas comes with its own limitations, considering that many people feel uncomfortable reporting on their relatives and friends to the authorities. A concerted effort, which also requires compliance and cooperation on the part of the community members, may assist in effectively addressing the risks of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mr Owen Mangiza is a Lecturer, and Dr Joshua Chakawa is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at Midlands State University.

Endnotes

- Dube, F. 2009. Colonialism, cross-border movements, and epidemiology: A history of public health in the Manica Region of Central Mozambique and Eastern Zimbabwe and the African response, 1890–1980. PhD Thesis, University of Iowa, p. 33. Available from: <https://ir.uiowa.edu> [Accessed 28 July 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p. 35.

- Kachena, L. and Spiege, S.J. 2019. Borderland migration, mining and trans-frontier conservation: Question of belonging along Zimbabwe-Mozambique border. GeoJournal, 84, pp. 1021–2019. Available from: <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10708-018-9905-0> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Eilenberg, M. and Wedley, R.L. 2009. Borderland livelihood strategies: The socio-economic significance in cross-border labour migration, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 50(1), pp. 58–73. Available from: <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8373.2009.01381.x> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- Ibid.

- Marara, P. 2020. Interview with the authors on 28 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Marutso, J. 2020. Interview with the authors on 25 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Marara, P. 2020. Interview with the authors on 28 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Marujata, R. 2020. Interview with the authors on 31 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Matenga, M. 2020. Zimbabwe closes borders after Covid-19 death. Newsday, 24 March. Available from: <https://www.newsday.co.zw/2020/03/zim-closes-borders-after-covid-19-death> [Accessed 29 July 2020].

- Ibid.

- Africa Press Agency Mozambique. 2020. Mozambique closes schools, tightens border controls. Africa Press Agency, 20 March. Available from: <https://www.newsday.co.zw/2020/03/zim-closes-borders-after-covid-19-death> [Accessed 20 March 2020].

- Matenga, M. 2020. Zimbabwe closes borders after Covid-19 death. Newsday, 24 March. Available from: <https://www.newsday.co.zw/2020/03/zim-closes-borders-after-covid-19-death> [Accessed 29 July 2020].

- Marara, P. 2020. Interview with the authors on 28 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Marujata, R. 2020. Interview with the authors on 31 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Herald Reporter. 2020. Ban on second-hand clothes to be enforced. Herald, 6 May. Available from: <https://www.herald.co.zw/ban-on-second-hand-clothes-to-be-enforced> [Accessed 29 July 2020].

- Kachena, L. and Spiege, S.J. 2019. Borderland migration, mining and trans-frontier conservation: Question of belonging along Zimbabwe-Mozambique border. GeoJournal, 84, pp. 1021–2019. Available from: <https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10708-018-9905-0> [Accessed 8 December 2020].

- Ibid.

- Marutso, J. 2020. Interview with the authors on 25 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Jachi, R. 2020. Interview with the authors on 27 July, Chipinge, Zimbabwe.

- Tshuma, A. 2020. Covid-19 mystery source worries health experts. The Chronicle, 3 July. Available from: <https://www.chronicle.co.zw/covid-19-infections-mystery-source-worries-health-experts> [Accessed 29 July 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Nyati, K. 2020. Desperate traders risk virus spread to smuggle bales into Zimbabwe. The East African, 11 May. Available from: <https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/business/Traders-risk-virus-spread-to-smuggle-bales-into-Zimbabwe/2560-5547164-jqgps0/index.html> [Accessed 3 June 2020].

- Dube, S. Chiefs enforce lockdown in rural areas. The Chronicle, 25 June. Available from: <https://www.chronicle.co.zw/chiefs-enforce-lock-down-in-rural-areas> [Accessed 25 August 2020.

- World Vision Zimbabwe. 2020. World Vision assists with Covid-19 preparedness at Tongogara Refugee Camp in Chipinge, Zimbabwe. World Vision Zimbabwe, 1 June. Available from: <https://www.wvi.org/stories/zimbabwe/world-vision-assists-covid-19-preparedness-tongogara-refugee-camp-chipinge> [Accessed 3 June 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Chuma, A. 2020. Police call for attitude change. The Chronicle, 11 August. Available from: <https://www.chronicle.co.zw/police-call-for-attitude-change> [Accessed 25 August 2020].

- Dube, S. Chiefs enforce lockdown in rural areas. The Chronicle, 25 June. Available from: <https://www.chronicle.co.zw/chiefs-enforce-lock-down-in-rural-areas> [Accessed 25 August 2020].

By:

Owen Mangiza