- Policy & Practice Brief

Secessionists Movements and their Implications for Security in Africa: The Case of Southern Cameroons

Secessionist movements have become a norm in some post-independence African states, leading to violent conflict and civil war. This PPB examines the factors influencing secessionist movements in Cameroon.

Executive Summary

Secessionism, as the creation of a state using violence without the consent of the former sovereign state, has occurred for centuries. Secessionist movements arose in the aftermath of the First and Second World Wars and during and after the Cold War. The cases of Ethiopia and Eritrea, and Sudan and South Sudan are examples of such movements occurring when a territory splits from an existing state, even though the seceding entity has no legal basis upon which to do so. This is because the legal grounds for statehood stem from the United Nations (UN) Charter, which entitles a colonised people, or people subject to foreign domination, to form a separate state. Nevertheless, secessionist movements have become a norm in some post-independence African states, leading to violent conflict and civil war.

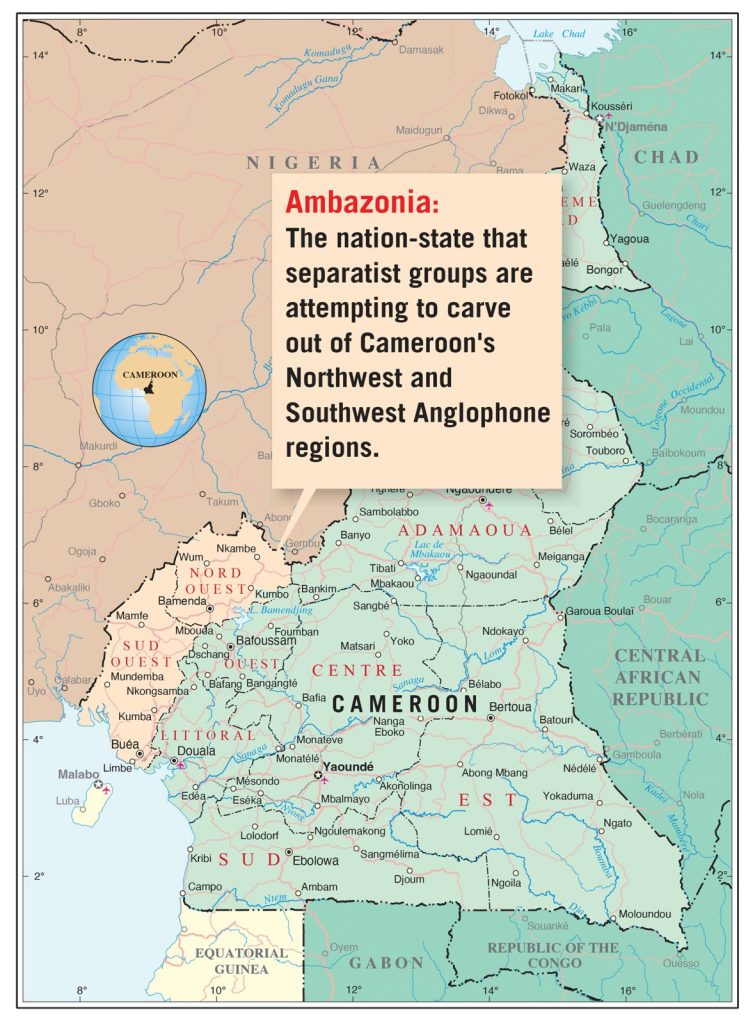

Many scholars have argued that the inherited colonial borders in Africa are one of the root causes for secessionist movements, as these borders have remained porous due to a lack of proper demarcation and delimitation. However, the case of conflict recurrence in South Sudan proves that this argument is unsubstantiated. This is because the crisis is political and thus requires that political measures be explored for its resolution. This Policy and Practice Brief (PPB) examines the factors influencing secessionist movements in Cameroon (Southern Cameroons Aka Ambazonia) and their implications for subregional and regional security in Africa. The paper concludes with recommendations based on this analysis.

Introduction

The ‘Anglophone problem’ in Southern Cameroons and what is referred to as its ‘attempted secession’ by the government of Cameroon has provoked renewed debate about the relevance of the idea of ‘self-determination’ in the 21st century. Moreover, the Anglophone problem poses a challenge not only to the efforts of the postcolonial state to forge national unity and integration 49Konings, P. and Nyamnjoh F.B. (2019) ‘Anglophone Secessionist Movements in Cameroon’,In Secessionism in African Politics, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 59-89. but to national and regional human security as well.

The conflict in Cameroon’s Anglophone Northwest and Southwest regions – the former British colony and mandate territory of Southern Cameroons – began on 11 October 2016 with peaceful protests by Anglophone lawyers and teachers. This was triggered by the central government’s placement of French-speaking judges and teachers in English-language courts and schools, including a systematic erosion of Anglophone common law procedures.

The disproportionate use of force fanned the flames of violence and led to a humanitarian disaster. 50Caxton, A.S. (2017) ‘The Anglophone Dilemma in Cameroon: The Need for Comprehensive Dialogue and Reform’, Conflict Trends, 2, 18-26.When, from 1 October 2017 onwards, militant secessionist groups symbolically proclaimed the restoration of the former Southern Cameroons as the state of Ambazonia, the government responded forcefully. Security forces arrested hundreds of demonstrators, including children, killed at least four people, and wounded many more. 51Human Rights Watch (2018) ‘“These Killings Can Be Stopped”: Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions’, Available at: <https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/07/19/these-killings-can-be-stopped/abuses-government-and-separatist-groups-cameroons> [Date accessed: 10 April 2021].

The ongoing fighting between separatists and security forces has displaced more than 700 000 civilians and driven 63 800 more into neighbouring Nigeria. It has also claimed the lives of about 4 000 civilians,52Craig, J. (2021a) ‘Violence in Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis Takes High Civilian Toll’, Aljazeera, 1 April, Available at: <https://www. aljazeera.com/news/2021/4/1/violence-in-cameroonanglophone-crisis-takes-high-civilian-toll> [Date accessed: 15 March 2021]. besides those of members of the state security forces as well as separatists. To date, Cameroon’s international partners and the international community, in general, have been silent on these events.53ICG (2017) ‘Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis at the Crossroads’, Available at: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/central-africa/cameroon/250-cameroons-anglophone-crisis-crossroads> [Date accessed: 2 June 2021]. This is partly because the Anglophone crisis has been underreported, leading to low levels of international awareness and recognition. 54Samah, W. and E S Tata, E.S. (2021) ‘Straddled Between Government Forces and Armed Separatists: The Plight of Internally Displaced Persons from the Anglophone Regions of Cameroon, In National Protection of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa: Beyond the Rhetoric, Cham: Springer, p. 73; Lamarche, A. and Fox, A. (2019) ‘Crisis Denied in Cameroon: Government Refusal to Recognize Suffering in NW SW Deters Donors’, Refugee International, Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/506c8ea1e4b01d9450dd53f5/t/5cf8872eee4d250001a5b850/1559791414017/Cameroon+Report+-+May+2019+-+final.pdf [Date accessed: 15 April 2021].

This PPB addresses the ‘war of independence’ in the former Southern Cameroons in this context. First, it considers its causes and whether they can be addressed. Next, it reviews the responses of the Cameroonian government and the international community. Lastly, it draws out the implications of the conflict for human and national security and, by extension, regional security.

Reasons for the Attempted Restoration of Southern Cameroons

The attempted secession of the Northwest and Southwest regions and restoration of Southern Cameroons in the form of the independent state of Ambazonia have multiple causes. They stem from a poorly organised UN process for granting independence and the subsequent reunification of the British-controlled Southern Cameroons with French Cameroon, political grievances, and ongoing economic and sociocultural inequalities.

To understand the current situation, one needs to examine events prior to independence. They can only be understood in terms of the strategies adopted by the British and French acting as the UN-mandated colonial masters of the two Cameroons.

Cameroon has a large and heterogeneous population of about 24 million people belonging to more than 250 ethnic groups with their own languages and customs 55Fombad, C.M. (1991) ‘The Scope for Uniform National Laws in Cameroon’, Journal of Modern African Studies,29(3), pp. 445–46.spread over ten regions. The Northwest and Southwest regions – more or less comprising the former British colony of Southern Cameroons – are home to an estimated five million people occupying about 16 000 square kilometres out of almost 475 000 square kilometres making up the larger Cameroon state and is home to about 5 million people .56ICG (2017) op. cit.

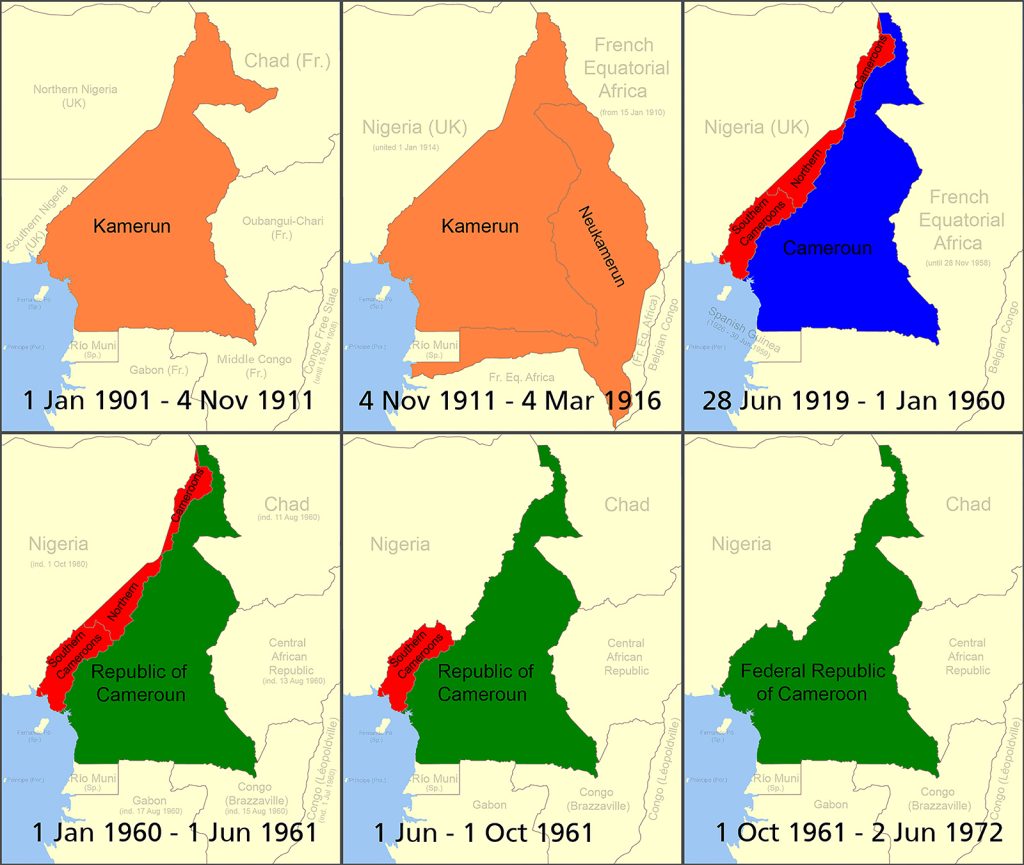

From 1884 to 1916, Cameroon was a German colony called ‘Kamerun’. After Germany’s defeat in the First World War, it was unequally divided between the French and British, with the former occupying four-fifths of the territory, and the latter one-fifth. The British divided their portion into British Northern and Southern Cameroons, and the France renamed its colony French Cameroon. 57Elango, L. (1985) ‘The Anglo-French “Condominium” in Cameroon, 1914-1916: The Myth and the Reality’, International Journal of African Historical Studies, 18(4), 657-673; Enonchong, L. (2020) The Constitution and Governance in Cameroon, Routledge: London.

In June 1919, the Treaty of Versailles established the mandate system for placing conquered colonies under international administration. Under this system, British and French Cameroon were administered by the two colonial powers from 1922 until 1945, when the mandates were replaced by trusteeship agreements under the auspices of the newly formed UN. For the sake of convenience, the British administered its territory (both Southern and Northern Cameroons) as part of the British colony of Nigeria. As elsewhere, the British and French adopted divergent approaches to administering the territories under their control – the former utilised their system of indirect rule, and the latter their policy of assimilation. In line with this, Southern Cameroons adopted an Anglo-Saxon governance culture, and French Cameroon, a centralised republican system. These divergent approaches had far-reaching consequences in respect of language, culture, systems of governance, judicial systems, and approaches to basic freedoms.58Musah, C.P. (2020) ‘Linguistic Segregation in Cameroon: A Systematic tool for the Assimilation of the Anglophones’, Asian Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, 3(3), 35-44.

Indeed, scholars agree that the systematic partition and subsequent administration of the two Cameroons by the French and British laid the foundation for the historical and spatial construction of Anglophone and Francophone identities in the territory.59Konings, P. and Nyamnjoh, F.B. (2019) ‘Anglophone Secessionist Movements in Cameroon’,In Secessionism in African Politics, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp. 59-89. By extension, these systems and identities prevailed even after independence.

French Cameroon became independent on 1 January 1960, being the second French colony in sub-Saharan Africa to do so. While Nigeria became independent on 1 October in the same year, Southern Cameroons remained in limbo, as it did not want to join either Nigeria or French Cameroon. The indecision of the Southern Cameroons elite prompted the UN to organise a referendum on 11 February 1961, offering voters the choice between joining the former French Cameroon or Nigeria. However, they were not presented with a third choice, namely, to become an independent state. Under these circumstances, Southern Cameroonians voted in favour of what they considered the lesser of the two evils: reunification with French Cameroon, despite the substantial differences in cultural heritage that had developed by this time. As Susungi has noted, ‘far from being the coming together of two prodigal sons who had been unjustly separated at birth, [reunification] was more like a loveless UN-arranged marriage between two people who hardly knew each other.’60Susungi, N.N. (1991) The Crisis of Unity and Democracy in Cameroon, s.n(no publisher mentioned).

In the same referendum, Northern Cameroons (the northern portion of British Cameroons), which had a Muslim majority, opted for union with Nigeria. Today, the former Northern Cameroons forms parts of the Borno, Adamawa, and Taraba states of Nigeria. Southern Cameroonians hoped they would be able to preserve and protect their Anglophone identity in a loose federal union61Konings, P. and Nyamnjoh, F.B. (2019) op. cit.

and that this would be assured in constitutional negotiations prior to reunification. Discussions began at a conference in London in 1960 which provided, inter alia, that specific arrangements for the governance framework between Southern Cameroons and the Republic of Cameroon would be worked out at a later conference consisting of representative delegations of equal status from both entities. This conference was attended by two delegations with equal status.62Enonchong, L. (2021) op. cit.

In July 1961, a conference was held in the Cameroonian town of Foumban aimed at drafting a constitution. The Southern Cameroonian delegation favoured a loose union that would allow a degree of cultural autonomy. However, the French Cameroon delegation led by President Ahmadou Ahidjo sought to consolidate the latter’s centralised executive powers and extend them over Southern Cameroons as well.63Ibid.

The Foumban conference was followed by a meeting of the governing delegation of the Southern Cameroons led by Premier John Ngu Foncha and President Ahidjo in Yaoundé in August 1961. This resulted in the adoption of the Constitution of the Federal Republic by the National Assembly of the Republic of Cameroon. Significantly, neither UN nor British representatives were present at these two meetings. Moreover, the Southern Cameroons House of Assembly did not adopt the Constitution, raising a fundamental question about its legitimacy.64Ibid.

Pierre Messmer, one of the last French high commissioners in Cameroon and a confidante of President Ahidjo, has been quoted as saying that he and other key role players were aware at the time that the new Constitution provided for a ‘sham federation’, which really amounted to an ‘annexation of West Cameroon’ (the former Southern Cameroons).65Anyangwe, C. (2009) Betrayal of Too Trusting a People: The UN, the UK and the Trust Territory of the Southern Cameroons, Oxford: African Books Collective.Ahidjo’s bad faith was further demonstrated when, in the guise of a referendum held on 20 May 1972, he unilaterally decided to abolish the Federal Constitution in direct contravention of the Constitution’s provisions. These events allowed the Anglophone movements to claim, in 1993, that the union between Southern Cameroons and the Republic of Cameroon ‘had proceeded without any constitutional basis’. These manoeuvres and betrayals are the root cause of the ‘Anglophone problem’. Other contributing factors are further examined below.

Political and Socioeconomic Inequalities

As foreseen by the Anglophone elite in Southern Cameroons, reunification resulted in the territory being marginalised. This was reflected in worsening political, social and economic inequality. Political power was consolidated in the hands of the Francophone majority and a few members of the Anglophone elite.66Chapman, M. and Pratt, D. (2019) ‘An Ambazonian Theology? A Theological Approach to the Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon’, HTS: Theological Studies, 75(4), 1-11. This asymmetry has manifested in various ways.

Prior to reunification, Southern Cameroons was endowed with various economic assets, such as the West Cameroon Marketing Board, the Cameroon Bank and Powercam, the port of Limbé, and the airports at Bamenda and Tiko.67ICG (2017) op. cit. However, after independence and reunification, these structures and projects were neglected and allowed to fall into ruin.68Mbaku, J.M. (2004) ‘Economic Dependence in Cameroon: SAPs and the Bretton Woods Agreement’ In J Mbaku & J Takougang (eds), The Leadership Challenge in Africa: Cameroon under Paul Biya Trenton, Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press; Anyefru, E. (2010) ‘Paradoxes of Internationalization of the Anglophone Problem in Cameroon’, Journal of Contemporary African Studies,8(1), 85-101. Indeed, the Anglophone regions are among the most poverty-stricken and unequal in the country,69Kumase, W.A.N. (2018) Aspects of Poverty and Inequality in Cameroon, Bern: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. trailing in terms of schools, hospitals, roads, and market centres, despite the region’s government-controlled oil wells being a key contributor to the Cameroonian economy. Moreover, managerial positions in public parastatals, such as the SONARA oil refinery and the Cameroon Development Cooperation (CDC) Banana Plantation in Tiko, are largely occupied by French-speaking Cameroonians.70Agwanda, B., Nyadera, I.N, and Asal, U.Y. (2020) ‘Cameroon and the Anglophone Crisis’, In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Peace and Conflict Studies, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

According to the Institute for Peace and Security Studies (IPSS) at Addis Ababa University, the two Anglophone regions lag behind the French regions in terms of public investment. In a 2020 report, the IPSS stated that, in the 2017 budget, the French-speaking Southern region was allocated some 570 projects valued at more than $225 million, the English-speaking Northwest region has some 500 projects worth more than $76 million, and the English-speaking Southwest region some 500 projects worth about $77 million.71IPSS (2020) ‘Cameroon Conflict Insight: Peace and Security Report’, March, Available at: https://ipss-addis.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Cameroon-Conflict-Insights-vol-1-Conflict-Insight-and-Analysis_342020.pdf [Date accessed: 21 March 2021] This is not an exhaustive list, however.

The political and social dynamics are similarly unbalanced. The Anglophone minority are under-represented in key government positions as well as the civil service. For instance, of the 67 members of government, only three Anglophones occupy high-level Cabinet positions. The Speaker of the National Assembly, Minister for Justice and Legal Affairs, Keeper of the Seal, Chief Justice, and Minister for Finance are all Francophone Cameroonians.72Ibid; Takougang, J. (1993) ‘Politics: The Demise of Biya’s New Deal in Cameroon, 1982–1992’, Africa Insight, 23(2), 91-101. Nfi notes that from the time of the late President Ahidjo to the present regime of President Paul Biya, the Francophonisation of Anglophones has been the dominant modus operandi. For instance, French dominates English in administration, education, and the media. Many schools and other educational institutions in Anglophone Cameroon have been staffed with Francophones who teach lessons and set examinations in French or Pidgin English.73Nfi, J.L. (2014) ‘The Anglophone Cultural Identity in Cameroon 50 Years after Reunification’, International Journal of Advanced Research, 2(2), 121-129.

Anglophone frustrations extend to the judiciary as well. For instance, according to the IPSS, in 2016, some 1 265 magistrates were French-speaking and only 227 English-speaking; and of 514 judicial officers, 499 were Francophone and 15 Anglophone.74IPSS (2020) op. cit.. Anglophones claim that even when they are nominated, they are forced to play subordinate roles, irrespective of merit or competence.75Lohkoko, E.A. (2013) ‘Cameroon: A Conflict Profile’, Conflict Studies Quarterly, 2, 3-29.

Impact on Human, National and Regional Security

The conflict has claimed significant casualties on both sides of the divide, and both the military and separatist or secessionist groups have targeted innocent civilians.

In April 2021, Jess Craig wrote that the worsening violence in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions was taking an increasingly heavy toll on civilians, with renewed attacks on schools and a spate of incidents involving improvised explosive devices and extrajudicial killings documented in recent months. Citing a UN report, he wrote that the five-year-old conflict between government security forces and armed separatists had displaced more than 700 000 civilians and forced another 63 800 across the Nigerian border.76Craig, J. (2021b) ‘Separatist Movements in Nigeria and Cameroon are Joining Forces’, Foreign Policy, 20 May, Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/05/20/separatistsnigeria-cameroon-biafra-ipob-ambazonia-anglophonejoining-forces [Date accessed: 11 March 2021]; Izobo, M. (2020) ‘Africa is Bleeding: The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon’, Daily Maverick, 1 November, Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-11-01-africa-isbleeding-the-anglophone-crisis-in-cameroon [Date accessed: 21 March 2021].

Overall, the UN estimated that three million of the four million people in Cameroon’s Northwest and Southwest have been affected. At least 4 000 civilians had been killed in the Anglophone regions, a toll surpassing that in the Far North region, where Boko Haram had been waging an armed campaign since 2014.77Ibid.

In May 2021, in a report for Foreign Policy magazine, Craig wrote that for the previous five years, factions of a secessionist movement in south eastern Nigeria and a pro-independence movement in western Cameroon had been gathering momentum, mobilising supporters through social media, and clashing with government security forces in both countries.78Craig, J. (2021b) op. cit.

In April 2021, leaders of both movements announced a formal alliance with the potential to ignite violence and instability in the two countries and across the West and Central African regions, where violent extremist organisations affiliated with the Islamic State and al Qaeda were establishing a foothold. In early April, Cho Ayaba, leader of the Ambazonia Governing Council, and the Biafran leader Nnamdi Kanu appeared at a press conference live streamed on social media to announce a strategic and military alliance. Representatives of both movements said they would work to ‘secure their shared border and ensure an open exchange of weapons and personnel’.79Ibid.

Craig added that the Biafran and Ambazonian movements were both fractured, and not all factions supported the alliance and rising violence.80Ibid. However, escalating violence in southeastern Nigeria and western Cameroon could only add to national and regional security challenges at a time when the region was already struggling with plummeting economies, democratic backsliding, and a resurgence of violent extremism and terrorism.

Therefore, the stakes are high, particularly considering that the announcement of a formal alliance between these movements could ignite violence and instability in the two countries and across the West and Central African regions.

The outbreak of war in the Anglophone regions has paralysed businesses, especially with the advent of separatist organised and respected ghost towns. Among other things, food supply lines from the rural areas to the cities and towns have been disrupted.81Nwati, M.T. (2021) ‘The Anglophone Crisis: The Rise of Arms Trafficking and Smuggling, its Effects on the Two English Regions of Cameroon’, Advances in Applied Sociology, 11(1), 1-13. The education sector has also been badly affected. Wanton kidnapping has taken hold and become a new norm in the English-speaking regions, with children and teachers being used as bargaining chips.82Krippahl, C. (2019) ‘Cameroon: Anglophone Separatists “Use Children as a Bargaining Chip”’, Deutsche Welle, 20 February, Available at: <https://www.dw.com/en/cameroon-anglophone-separatists-use-children-as-a-bargaining-chip/a-47602429> [Date accessed: 05 June 2021]. Schools have been shut down and destroyed,83Tah, P. (2019) ‘Cameroon’s Conflict Keeps Schools Shut’, BBC News, 3 September, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-49529774> [Date accessed: 21 April 2021]. and water and electricity supplies have been cut off for weeks on end. Moreover, since 2016, rural health services have been disrupted due to shortages of health personnel, damaged or destroyed health facilities, and restrictions on freedom of movement, including ongoing roadblock.84Nwati, M.T. (2021) op. cit. According to Insecurity Insight, humanitarian access to the Anglophone regions has deteriorated. Aid workers are often misinformed by people linked to the separatist movement and have been kidnapped individually or in groups.85Insecurity Insight (2021) ‘Cameroon’, Available at: <http://insecurityinsight.org/country-pages/Cameroon> [Date accessed: 15 April 2021].

Government Response

When the crisis began in 2016, the Cameroon government was in denial. This included, among others, Paul Atanga Nji, the Minister in charge of Special Duties in the Presidency at the time, and the Minister of ommunication, Issa Tchiroma Bakary, who rejected the notion of an ‘Anglophone crisis’.86Kamé, B.P. (2018) The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon,Translated by Tezeh, F.M., Paris: L’Harmattan; Ayang, M. (2016) ‘Atanga Nji Warns Anglophone Agitators: Violence Will Meet with Merciless Repression’, The Guardian Post, 25 November; Kinsai, N.S. and Mengnjo, E.M. (2016) ‘Anglophone Complaints Are Useless – Issa Tchiroma’., The Post, 28 November. However, from 2017 onwards, the government adopted a more cohesive and militarised approach, banning protests and arresting and detaining leading protesters.87Atabong, A.B. (2017) ‘Anglophone Crisis: Consortium President, Secretary General Arrested’, The Guardian Post, 18 January; Amin, J.A. (2021) ‘President Paul Biya and Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis: A Catalogue of Miscalculations’, Africa Today, 68(1). At the same time, it established a commission for promoting bilingualism and multiculturalism. This was followed by a commission on disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration, and the granting of ‘special status’ to English-speaking regions after the October 2019 national dialogue.88Diatta, M., Woldemichael, S., Handy, P.S., and Hoinathy, R. (2021) ‘No More Half Measures in Cameroon’s Anglophone Crisis’, ISS Peace and Security Council Report, 34, 11-12. However, these measures have been rejected as poorly planned and superficial. For instance, the ‘National Dialogue’ held in October 2019 suffered from a lack of prior consultation and failed to address the core issue, namely, statehood. The granting of ‘special status’ and other measures emanating from the dialogue were regarded as inadequate because they only benefited administrative elites.

International and Regional Response

The international reaction to the Anglophone crisis has been marred by rhetorical innuendos, with little or no concrete action taken. For instance, the African Union’s (AU) apparent unwillingness to intervene is not surprising. When the crisis started escalating in 2017, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, then Chair of the AU Commission, issued a statement calling for restraint, while encouraging the Cameroonian government to continue engaging in dialogue as a means of finding a lasting solution.89Bareta, M. (2017) ‘AU Offers to Negotiate: Calls for Restraint and Effective Dialogue’, Bareta News, 26 January, Available at: <https://www.bareta.news/au-offers-negotiate-calls-restraint-effective-dialogue> [Date accessed: 15 April 2021]. Two years later, in 2018, during a two-day visit to Cameroon, the current AU Chair, Moussa Mahamat Faki, called for an inclusive dialogue involving all stakeholders ‘based on national leadership and ownership’.90AU (2018) ‘Readout of the Visit of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission to Cameroon’, 16 July, Available at: https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20180716/readout-visitchairperson-african-union-commission-cameroon [Date accessed: 10 March 2021 ].

However, the AU’s approach towards the resolution of the crisis has been sharply criticised by human rights groups and other observers. Netsanet Belay, Africa Director of Amnesty International, criticised the AU for its ‘persistent inability… to marshal the determination, political will and courage to hold member states to account for clear violations of AU principles, values and standards on especially human rights’91Durmaz, M. (2019) ‘The African Union’s Core Values are Under Threat with Sisi at the Helm’, TRT World, 13 February, Available at: <https://www.trtworld.com/africa/the-african-union-s-core-values-are-under-threat-with-sisi-at-the-helm-24102> [Date accessed: 30 March 2021]. However, neighbouring Nigeria has expressed its support for the Cameroonian government in its fight against the separatists. President Muhammadu Buhari has bluntly stated that Nigeria would ‘take necessary measures within the ambit of the law to ensure that its territory is not used as a staging area to destabilise another friendly sovereign country’.

African countries have opposed UN intervention on the multilateral front. For instance, Norway and the Netherlands attempted to introduce an agenda item on the crisis at the UN Security Council in 2020. This was brushed away after failing to garner the minimum nine out of 15 votes. Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Cote D’Ivoire and South Africa all voted against attempts to bring the crisis up for discussion in 2021.92ICG (2019) op. cit.; Vanguard News (2018) ‘Nigeria Will Not Be Used to Destabilise Cameroon – Buhari’, 12 February, Available at: <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2018/02/nigeria-ll-not-used-destabilise-cameroon-buhari> [Date accessed: 21 March 2021]. The relatively muted reaction of some African states is not surprising, however, considering they are faced with similar security issues linked to secession.

By contrast, in April 2019, the European Parliament adopted a resolution calling on the Cameroonian government to ‘organise an inclusive political dialogue aimed at finding a peaceful and lasting solution to the crisis in the Anglophone regions’, urging the AU and the Economic Community of the Central African States (ECCAS) to push for talks, and calling for the European Union (EU) to support this process.93EU (2018) ‘European Parliament Resolution of 18 April 2019 on Cameroon’, Available at: <https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2019-0423_EN.html> [Date accessed: 15 April 2021]. In March 2019, the United States (US) Undersecretary of State for African Affairs, Tibor Nagy, visited Cameroon and held talks with President Biya. Following the visit, he reportedly called for the release of Maurice Kamto, leader of the Movement for the Renaissance of Cameroon, and fellow activists. He further stated that the Cameroonian authorities needed to be ‘more serious in their management of the Anglophone crisis’.94Tantoh, M., (2019) ‘Cameroon: US and Europe Turn Up the Heat on Govt’, AllAfrica, 6 March, Available at: <https://allafrica.com/stories/201903060683.html> [Date accessed: 16 April 2021].

In July 2019, the US House of Representatives passed Resolution 358, calling on the conflicting parties to ‘respect the human rights of all Cameroonian citizens, to end all violence, and to pursue a broad-based dialogue without preconditions to resolve the conflict in the Northwest and Southwest regions’.95US House of Representatives (2019) ‘H Res 358 (IH) – Calling on the Government of Cameroon and Armed Groups to Respect the Human Rights of all Cameroonian Citizens, to End All Violence, and to Pursue a Broad-Based Dialogue Without Preconditions to Resolve the Conflict in the Northwest and Southwest Regions’, Available at: <https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BILLS-116hres358ih> [Date accessed: 21 April 2021].And, on 7 June 2019, the US Secretary of State, Anthony J. Blinken, announced visa restrictions on ‘individuals who are believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the peaceful resolution of the crisis in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon’96Chimtom, N.G. (2021) ‘U.S. sanctions for Cameroon Anglophone Crisis are “Cosmetic”, Bishop says’, CRUX, 12 June, Available at: <https://cruxnow.com/church-in-africa/2021/06/u-s-sanctions-for-cameroon-anglophone-crisis-are-cosmetic-bishop-says> [Date accessed: 21 April 2021].. However, the recent visa restrictions will have very little impact because they do not target a specific group of people, whether they are in Cameroon or in the diaspora. If the US really wants to end this crisis, it should be more proactive by calling on all the belligerents (government and separatist leaders) at home and abroad to come to the negotiation table.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The Cameroon crisis threatens to destabilise the entire Central African region. It has reaffirmed that 60 years after reunification and independence, inherited borders have failed to secure the long-held ideal of national unity. Given growing perceptions on both sides that victory is unattainable, the time is ripe for a neutral party to step in and bring the disputants to the negotiating table. Moreover, as long as the conflict continues, more lives will be lost, and many more people will be displaced. This will also further strain an already ailing economy and probably increase regional instability, especially in a context where Cameroon is already menaced by insurgents from the south as a result of the instability in the Central African Republic (CAR), Boko Haram, and a fragile Chad from the north.

Both parties should take reconciliatory and concessionary steps to de-escalate the conflict. The government should also fully acknowledge the existence of the Anglophone problem, considering that many Francophone elites and government officials are still in denial.

The Anglophone crisis has demonstrated the limits – at least in Africa – of presidential centralism and a governance system that depends on co-option. Other governance systems and forms of statehood should be considered under which inherited cultures at independence could be harnessed for the benefit of the entire state.

Self-determination is often interpreted to mean the right to secede and declare independence. But it can also take other forms, such as local autonomy, similar to the autonomous rule Canada has granted to Québec, a federal system with a strong central government that protects minority rights, and/or a confederation of states.

Finally, there have been widespread calls for a referendum in Southern Cameroons as a means of resolving the ongoing crisis. It may be beneficial for the international community to step in and organise a referendum in which Southern Cameroonians could decide once and for all among separatist, federalist and unionist options.

Dr Anslem W. Adunimay is a Junior Research Fellow at ACCORD.

The original version of this article was first published on the site of the Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Johannesburg.