Executive Summary

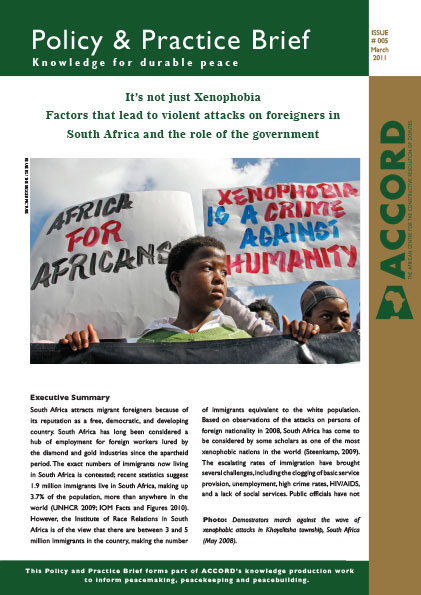

South Africa attracts migrant foreigners because of its reputation as a free, democratic, and developing country. South Africa has long been considered a hub of employment for foreign workers lured by the diamond and gold industries since the apartheid period. The exact numbers of immigrants now living in South Africa is contested; recent statistics suggest 1.9 million immigrants live in South Africa, making up 3.7% of the population, more than anywhere in the world (UNHCR 2009; IOM Facts and Figures 2010). However, the Institute of Race Relations in South Africa is of the view that there are between 3 and 5 million immigrants in the country, making the number of immigrants equivalent to the white population. Based on observations of the attacks on persons of foreign nationality in 2008, South Africa has come to be considered by some scholars as one of the most xenophobic nations in the world (Steenkamp, 2009). The escalating rates of immigration have brought several challenges, including the clogging of basic service provision, unemployment, high crime rates, HIV/AIDS, and a lack of social services. Public officials have not helped to subdue xenophobic sentiments; and sectors such as the South African Police Department and the Department of Home Affairs have publicly expressed xenophobic feelings towards foreigners. This fear or intolerance of non-nationals has perpetuated physical and verbal attacks, specifically on African migrants, in recent years. Yet it is not enough to just call it xenophobia. Like all occurrences of xenophobia, the South African case is based upon history and layered with factors that have allowed for the intensification of violence and hatred towards foreigners.

This analysis is written with the intention of informing policymakers and practitioners about the history and multiple factors that have furthered xenophobic attitudes and trends in South Africa. One primary issue in curbing xenophobia is that of government involvement. With the 2011 South African Municipal Elections approaching, it is important to find solutions that protect foreigners during elections and that no longer tolerate the election of local leaders that hold or propagate xenophobic sentiments. This briefing therefore includes suggestions and recommendations on how to contribute to the eradication of xenophobia in South Africa.

Recommendations:

|

Introduction

There is a common xenophobic sentiment held by some in the South African community that the high rate of crime and violence – mostly gun running, drug trafficking and armed robbery – is directly related to the rising number of illegal migrants in South Africa (Human Sciences Research Council, 2008). A South African Migration Project (SAMP) study revealed that nationals of South Africa are “particularly intolerant of non-nationals, and especially African non-nationals” (Black et al., 2006:105). Furthermore, a national public opinion survey found South Africans to be exceptionally xenophobic. Results showed that 25% of South Africans interviewed want a total ban on immigration while 45% support strict limitations on the numbers of immigrants. Over half of respondents opposed offering African non-citizens the same access to housing as South Africans and 61% of respondents believed that immigrants placed additional strain on the economy. Of black respondents, 65% indicated that they would be “likely” or “very likely” to “take action” to prevent people from other countries operating a business in their area (Crush, 2000: 125).

Conceptualising xenophobia in South Africa

Xenophobia is defined by the Webster’s dictionary as “the fear and/or hatred of strangers or foreigners or of anything that is different or foreign“. There are those who have argued that this definition is too simple and that the concept of xenophobia includes an aspect of violence and physical abuse. Jody Kollapan, former Chairperson of South Africa’s Human Rights Commission, contends that the term xenophobia must embody action or practice and cannot merely be defined as an attitude (Kollapan, 1999). This argument implies that beyond dislike and fear there must be actions of violence that result in bodily harm or damage to property (Harris, 2002). The definition of xenophobia must be further refined to include a specific target of particular individuals or groups against whom the fear and hate or actions of violence are directed. The South African case presents all three ingredients: a demonstrated fear or hate of black foreigners accompanied by violent actions, resulting in loss of life and property.

To significantly understand the xenophobic crisis in South Africa one must find its basis in the historical accounts of foreigners within the country. Over the years South Africa has been host to a variety of African immigrants, many of them refugees: in the 1980s Mozambicans; in the early 1990s Nigerians and other immigrants from Angola, Somalia, Rwanda, and Burundi; in the late 1990s immigrants from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; and more recently immigrants have included Zimbabweans fleeing the political and humanitarian crisis in their own country (McKnight, 2008).

Xenophobic tendencies against foreign migrants, and more specifically African migrants, have only been documented since 1994. Since then there has been evidence that xenophobic tendencies in South Africa have increased over the years as the number of foreigners has increased (HSRC, 2008). Black foreigners in South Africa have often been referred to as “amakwerekwere” or “amagrigamba“, these terms are derogatory and are used to inflict intimidation and hate on immigrants (Jere, 2008). The Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), in its 2008 research, identified two main patterns of the xenophobic culture in South Africa: firstly, that the violence was mostly aimed at other African nationals and not against foreigners in general; and secondly, that the violence was largely confined to the urban informal settlements in South Africa’s major cities (HSRC, 2008). A few examples of these xenophobic trends are the following: In 1995 there was the assault on Malawian, Mozambican and Zimbabwean immigrants living in Alexandra township in a campaign known as “Buyelekhaya” (go back home), under the suspicion that they were guilty of crime and sexual attacks, and that they were causing increased unemployment; two years later, a Mozambican and two Senegalese men were attacked by a group returning from a rally that blamed immigrants for crime, unemployment and the spreading of AIDS (Human Rights Watch, 1998); and in 2005 twenty Somali traders in Cape Town were murdered by locals.

While the above mentioned cases had been isolated incidents, in May 2008 the attacks on foreigners consumed several cities and townships throughout the country for weeks. The violence began in the township of Alexandra, north of Johannesburg, following a local meeting to address tensions between locals and foreigners in the area and then spread to other areas in and around Johannesburg, to the provinces of Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal, and to Cape Town (Landau and Segatti, 2009, cited in HSRC, 2008). In the days and months following the attacks 62 deaths were documented, of which 21 were believed to be South Africans, over 100,000 people were displaced from their homes, and property of millions of rand looted (Misago, Landau and Monson 2009, 7–12).

Theoretical explanations of xenophobia in South Africa

Different scholars have tried to explain and contextualise xenophobia in South Africa. One such theoretical explanation is the scapegoating hypothesis (Harris, 2002). In this sociological theory xenophobia is seen within the context of social transition and change. Rejection of or hostility to foreigners in South Africa is related to limited resources, such as housing, education, health care and employment, in a period marked with high expectations, especially for black South Africans (Morris, 1998). A common belief in South Africa is that every job given to a foreign national is one less job for a South African, and this is exacerbated by the unemployment rates, currently in the range of 20–30%. Yet, no empirical evidence can support these beliefs, and some categories of migrant work have been shown to actually increase employment opportunities for South Africans (Black et al., 2006:117).

Furthermore, many foreigners find shelter in informal urban settlements characterised by high levels of poverty, unemployment and housing shortages.Thus competition for already limited resources is intense. This could explain in part a tendency to place black foreign nationals as the scapegoat for the increasing poverty and unemployment in South Africa. Immigrants are then seen as mere opportunists who are only in South Africa for economic benefits (McKnight, 2008). The HSRC in their primary research carried out in 2008 referred to this situation as relative depravation, which would explain the relationship between xenophobic violence and socioeconomic factors where inequality and poverty lead to feelings of deprivation (HSRC, 2008).

A second theoretical explanation to explain xenophobic tendencies in South Africa has been the isolation hypothesis. Here xenophobia is seen as a consequence of apartheid in South Africa (Morris, 1998). The seclusion of the country from the rest of the world in the apartheid era is taken to be an explanation for the fear and distrust that South African communities have towards foreigners. According to this theory, the freedom felt within South Africa in 1994 came with the ideology that the country must be protected from “outsiders”. In light of South Africa’s history it is reasonable that the country needed to put its citizens first in line for transformation and change. However, the closed-door migration policies, sluggish development and increase in poverty and inequality have provided a breeding ground for xenophobia. Following South Africa’s democratic transition, the Refugee Act took four years to draft and eight years to negotiate. One of the primary reasons it took South Africa so long to replace the apartheid regime’s Aliens Control Act was that the idea of migration created uncertainty in nationals and immigration was seen as “undesirable” (Crush, 2008:2).

Yet, despite resistance to foreigners, the democratic and political transition opened up South Africa’s borders and the country has gradually become more integrated into the international community. As a result this has brought South Africans into direct contact with unfamiliar foreigners. The hostility that developed as the result of this isolation is further compounded by the fact that many South Africans seem oblivious to the plight faced by many African foreigners and thus fail to show empathy towards these nationals. It is important to note here that whilst South Africans were recipients of regional support from their African counter-parts during the apartheid area, this assistance was mostly granted directly to the elites who fought for freedom and those who were exiled as a result of the apartheid regime. Not all South Africans are well versed with the contributions made by other African countries and this could contribute to the isolation hypothesis. Authors, like Bouillon, in support of the isolation hypothesis argue that black South Africans are just coming out of oppression. One of apartheid’s long lasting legacies can be seen in the isolation created amongst the population. It is this isolation which has closed society and created a nation that is unwelcoming of foreigners (Morris and Bouillon, 2001). The isolation theory’s contextualisation of xenophobia rests on the central premise that where a group has no history of interacting with the outside world and incorporating strangers, that group is blinded to the opportunities of welcoming those that may be different or foreign (Gounden, 2010) and this can be very well understood in the South African context after apartheid.

It is imperative to note that apartheid has had a bearing on what is perceived as the new South Africa. Apartheid South Africa did not recognize refugees until 1993. Only during the transition from apartheid to democratic rule did South Africa become a signatory to the UN and Organization of African Unity conventions on refugees and this has contributed to xenophobic tendencies.

A third theoretical explanation for xenophobia in South Africa is the bio-cultural hypothesis.This theory suggests that xenophobic violence is not applied equally to all foreigners. In the case of South Africa, black foreigners are at greater risk of violence than foreigners of other race groups (Human Rights Watch, 1998). Furthermore, as stated earlier, on arrival in South Africa many foreign nationals seek shelter in urban informal settlements where there is intense competition for basic resources. The bio-cultural hypothesis emphasises the levels of visible differences in the physical demeanour of other foreign Africans (Harris, 2002). This hypothesis could explain the violence targeted against even South Africans who were thought to be foreign on the basis of skin colour or speech. Of the 62 people who died in the 2008 attacks, 21 were South African citizens. As some of the local South African languages are spoken by neighbouring countries, this has led to cases where a local could be seen as a foreigner and targeted during xenophobic attacks (BBC, 2008).

Political contribution to xenophobia

While the theoretical hypotheses do give some form of contextualisation to the whole dilemma of xenophobia, they still fall short of offering an explanation as to why the xenophobic attacks have taken place in some areas of the country and not others.When looking at specific townships and settlements that have faced violent attacks on non-nationals, it is almost always rooted in the micro-politics of these areas. Local leaders often lead or organise violent attacks on foreign migrants in order to gain authority or realise their political interests (Misago 2009, cited in Amisi et al., 2010). Furthermore, as non-nationals have become increasingly unpopular throughout South Africa, local leaders often feel pressure to exclude foreigners from political participation or ostracise them in general because of their fear of losing their political positions. Because of this fear, some leaders have promoted violent practices against non-nationals in order to ensure their authority within the community.

In 2009 the South African newspaper Mail and Guardian highlighted a study by the International Office for Migration revealing that community leaders and the local government did nothing to prevent or stop violent attacks on foreigners. Furthermore, the study found that some were directly involved in attacks, while others were reluctant to assist foreigners for fear of losing legitimacy or positions in the 2009 elections (Mail and Guardian, 2009).

Similarly the Consortium of Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CORMSA) released an issue brief in 2010 stating:

The key trigger of violence against foreign nationals and outsiders in specific locations is localised competition for political (formal and informal) and economic power. Leaders, and aspirant leaders, often mobilise residents to attack and evict foreign nationals as a means of strengthening their personal and political or economic power within the local community (CORMSA, 2010:2).

Beyond local officials, national leaders have also used anti-immigration language during their campaigns in order to gain votes. In addition to the political callousness that has fed xenophobic trends in SouthAfrica there have been documented instances in which migrants have become targets of abuse in the hands of the police, the army and the department of Home Affairs. For example, the former Minister of Home Affairs, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, stated publicly, “If South Africans are going to compete for scarce resources with immigrants, then we can bid goodbye to our Reconstruction and Development Program” (Human Rights Watch, 2008:20).This kind of misuse of power and prejudiced speech has only contributed to the xenophobic sentiments being expressed by South African citizens and the widespread violent attacks.

Recommendations

- Acknowledgement of the problem: The first step to addressing this issue lies in the acknowledgment by the South African government, as well as local leadership, that xenophobia exists and is a real challenge in South Africa. Unless there is such acknowledgement it may be difficult to formulate policies that address the problem and protect people of foreign origin.

- Address the root causes of xenophobia: Greater attention must be given to understanding and addressing the root causes of xenophobia in South Africa. During the 2008 attacks the government was not actively involved in explaining to local communities who foreigners were and the reasons why they had come to South Africa. More research must be done into the reasons why there are xenophobic attacks, which groups are at a greater risk and what socio-economic factors increase these risks.

- Inform the public of the rights of refugees living in South Africa: Refugees and asylum seekers have been the most vulnerable to institutional abuse and xenophobic attacks (HSRC, 2008).Yet, South African legislation allows for refugees to enjoy the right to live where they desire, move about the country freely, as well as join the labour market and use social services offered to other citizens. However, these rights are neither well known nor respected throughout the country by both the public and government officials. Government authorities must be well educated about the rights of migrants and refugees in South Africa. There is plenty of informative research, especially after the 2008 xenophobic violence, which can provide greater insight into the plight and rights of migrants in South Africa and the South African Development Community as a region.

- Address labour disparities and encourage partnership and sharing: The government must be vigilant in enforcing the minimum wage requirement for all employers. There is a tendency for many foreigners, who are desperate to make a living, to work at exploitative rates beneath the minimum wage.This often then results in unfair competition for casual labour. The government must therefore work to ensure that they safeguard the labour provisions so as to rid the environment of instances of unfair competition between locals and foreigners. Ironically, in the midst of the “brain drain” dialogue, South Africa is host to a wealth of resources in the form of skilled migrants already in the country. Unfortunately, even with the need for skilled professionals in South Africa, these men and women are often unable to find work that matches their skills. For instance, legal migrants who are skilled in areas of plumbing, electronics and even engineering hold certifications that are not recognised within the country. Many of these foreigners must resort to finding less-skilled jobs, and it is often at this level that South Africans feel that their jobs are being “taken”. The government should develop programmes that will work to enhance and foster partnership between local populations and immigrant communities. For example, skills sharing between locals and migrants could provide a platform to forge relationships, deal with misconceptions about “foreigners”, and work to eliminate the fear and distrust that could result in situations of violence.These environments of sharing will provide avenues for creating a common identity of individuals working hard to skill themselves for a better and sustainable future, as such realising the spirit of “ubuntu” and oneness.

- Hold public officials, police officers, and local leaders accountable for their role in spreading xenophobia: The government needs to condemn and prosecute community leaders as well as other government officials who have been involved in committing, planning, or promoting xenophobic attacks. It is essential that hate speech be upheld as a crime, and speeches given by public personalities must be monitored in order to ensure that leaders are not elected on a basis of an anti-foreigner campaign. In addition, the Department of Provincial and Local Government (DPLG) should identify and apply sanctions to guilty parties and intolerable practices. The DPLG should also promote positive leadership and governance that respects the rule of law and the rights of refugees.

- Promote government and civil society coordination on tackling xenophobia: The Refugee Act places responsibility upon the South African government to provide full protection and provision of rights set out in the Constitution – this includes access to social security and assistance. In addition, on 12 January 1996, South Africa became a signatory to the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, obliging the state to provide equal treatment to refugees and nationals. However, the 2008 CORMSA migration report suggests that the implementation of rights and services of migrants have lagged, and migrants are likely to be excluded from basic social services. In addition to threats of violence, xenophobia keeps all migrants from vital services to which they may be entitled, including health and education (CORMSA,2008). Misunderstandings persist at the service provider level as to the rights of migrants – this is a primary cause of many migrants being turned away from basic and emergency healthcare services.The denial of services is a non- or miscommunication issue from the top down, due to the government not being active in educating government service providers about the rights of migrants within South Africa. Educating South Africans about the rights of refugees, monitoring local elections and leadership behaviour, and delivering social services are all actions that need to be taken by the government. However, in order to address xenophobia and deal with it successfully, civil society will also have to play a role in achieving these recommendations. It is important that the government, international and national non-governmental organisations, and the rest of civil society work together to resolve these conflicts if xenophobia is to be eradicated.

- The South African government and its agencies must protect persons of foreign origin: Whilst the South African government has legislated and allowed for the entry and stay of foreign nationals, these rights and regulations must be communicated to local populations. The Department of Home Affairs has a role to play in not only registering foreign nationals but also actively communicating the statistics and plight of immigrants and especially refugees. A mere directive to tolerate foreigners would be insufficient to protect groups of foreigners who bear the brunt of the everyday socio-economic frustrations of local populations. It is imperative to note that people will tend to empathise with others according to what they understand about them. Education and information sharing targeted at creating awareness and fostering a bond between immigrant communities and local communities would be a critical step in addressing the issues related to xenophobia.It is important to note here that the education the authors suggest includes teaching and informing the South African population of their solidarity with fellow African colleagues who stood with them during the apartheid period.There is little knowledge among the general South African population of the sacrifices and brotherhood and sisterhood that were extended to end the repressive apartheid regime. Whilst the legalistic information and knowledge of the rights of refugee populations is crucial, education on how the South African community fits into the African continent as a whole is imperative.

Conclusion

There is a tendency to blame the xenophobic violence on the unfortunate history of apartheid, and while this history may be a contributing cause, it is not in and of itself the only reason for xenophobic attacks.The high unemployment rate among black South Africans is a cause of concern and must be addressed if the frustration of social and economic deprivation is to be mitigated. Many people in various townships feel more oppressed economically than they did during apartheid (McKnight, 2008). This is not to say that the socio-economic struggles of the post-apartheid regime of South Africa are in any way a justification for the violence directed against immigrants. McKnight argues that there is an urgent need for a gradual and overall shift in South Africa’s isolated and exclusive culture.

These recommendations are not exhaustive but are initial steps through which the nation can begin to forge ahead and deal with the challenges of foreigners and their protection.

Creative policies and dialogue that recognise and accept migration as a continued phenomenon are needed within southern Africa. The response from leaders and government departments – more specifically, the Presidency and departments such as the Department of Social Development and the Department of Home Affairs – has the influence to either encourage or discourage xenophobia. Government has the mandate and the ability to provide safety and protection for those within its borders, and this includes non-citizens.

References

- BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) 2008. Locals killed in South African attacks. BBC News, 12 June. Available from: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7450799.stm> [Accessed 23 June 2010].

- Black, R., J. Crush, S. Peberdy, S. Ammassari, L. McLean Hilker, S. Mouillesseaux, C. Pooley and R. Rajkotia 2006. Migration and development in Africa: An overview. African Migration and Development Series No.1. South African Migration Project. Cape Town, IDASA. p. 105.

- Consortium of Refugees and Migrants in South Africa (CoRMSA) 2008. Protecting refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in South Africa. Available from: <http://www.cormsa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/cormsa08-final.pdf> [Accessed 27 November 2008] pp. 8–41.

- CoRMSA 2010. Migration Issue Brief 3: Xenophobia: Violence against foreign nationals and other outsiders in contemporary South Africa. June 2010. Available from <http://www.cormsa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/fmsp-migration-issue-brief-3-xenophobia-june-2010-1.pdf> [Accessed 23 March 2011] p.2

- Crush, J. Jonathan 2008. South Africa: Policy in the face of xenophobia. Migration information source. Available from: <http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/south-africa-policy-face-xenophobia> [Accessed 27 October 2008] p. 2.

- Crush, J. 2000. The Dark Side of Democracy: Migration, Xenophobia and Human Rights in South Africa in International Migration 38 (6): 103–133.

- Gounden, V. 2010. Xenophobia after the World Cup. Speech, 8 June. Durban.

- Harris, B. 2001. A foreign experience: Violence, crime, and xenophobia during South Africa’s transition. Violence and Transition Series, Volume 5, pp. 11–140.

- Harris, B. 2002. Xenophobia: A new pathology for a new South Africa? In: Hook, D. and G. Eagle, Psychopathology and social prejudice. Cape Town, University of Cape Town Press. pp. 169–184.

- Human Rights Watch 1998. Prohibited persons: Abuse of undocumented migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees in South Africa. Human Rights Watch, New York.

- Human Sciences Research Council 2008. Citizenship, violence and xenophobia in South Africa. Pretoria, HSRC.

- Jere, D. 2008. Zim exiles face new fear and loathing in SA. AFP, 14 May. Kollapan, J. 1999. Xenophobia in South Africa: The challenge to forced migration. Johannesburg, Unpublished seminar.

- Landau, L. and A. Segatti 2009. Human development impacts of migration: South Africa case study. Johannesburg, UNDP (United Nations Development Programme).

- Karim, Q. 2009. Local leaders behind xenophobic attacks. Mail and Guardian, Available from: <http://www.mg.co.za/article/2009-03-11-local-leaders-behind-xenophobic-attacks>

- McKnight, Janet 2008. Through the fear: a study of xenophobia in South Africa’s refugee system. Journal of Identity and Migration Studies (2), pp. 18–42.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/xenophobia> [Accessed 23 March 2011]

- Misago, J.P. 2009. Towards tolerance, law, and dignity: Addressing violence against foreign nationals in South Africa. International Organization for Migration. <http://www.migration.org.za/uploads/docs/report-12.pdf> [Accessed 23 March 2011] pp. 8–67.

- Morris, Allan. 1998. ‘Our fellow Africans make our lives hell’: The lives of Congolese and Nigerians living in Johannesburg. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21 (6), 1116–1136.

- Morris, Allan and Antoine Bouillon, eds., African Immigration to South Africa: Francophone migration of the 1990s, (Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2001)

- Neocosmos, M. 2006. From Foreign Natives to Native Foreigners: Explaining Xenophobia in Post-apartheid South Africa. CODESRIA: Dakar

- Steenkamp, C. 2009. Xenophobia in South Africa: What does it say about trust? The Round Table, 98 (403), pp. 439–447. Available through: Academic Search Complete [October 20, 2010].

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) 2009. African UNHCR Global Report. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org> pp. 135–138.