Executive Summary

Local integration continues to be an important option in the basket of comprehensive strategies to achieve long-term solutions to refugee crises, particularly those caused by protracted conflicts. While many refugees may voluntarily repatriate to their countries of origin, with some benefiting from resettlement in third countries, local integration presents a durable solution that is often not considered or applied. Zambia, with a high number of refugees living within its border, has long chosen to facilitate voluntary repatriation for emigrants; notwithstanding that not all refugees benefit from this solution. Realising this, the southern African nation of Zambia launched the Strategic Framework for the Local Integration of Former Angolan Refugees in Zambia2 to benefit those former refugees who chose not to return to their country of origin. This framework is a blueprint to support the local integration of 10000 eligible former Angolan refugees who have been living in Zambia for over four decades, among them second and third generation refugees born in the country. In the same vein, Zambia also committed to integrate 4000 former Rwandese refugees as the next step. With particular emphasis on Angolan refugees in Zambia, this Policy & Practice Brief (PPB) analyses the implementation of the strategic framework, highlighting the socio-economic situation of former Angolan refugees that make this a viable approach for Zambia. The brief concludes by advancing recommendations that the Zambian government can adopt to effectively address weaknesses in the overall local integration process.

Introduction

The conflict-induced movement of people across national borders remains one of the most complicated challenges confronting the world. Millions of refugees in countries around the world continue to live with little hope of finding solutions to their plights, posing a major challenge to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the international community, host countries, and refugees themselves.3 The number of refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons (IDPs) worldwide has, for the first time in the post-World War II era, exceeded 50 million people. Half of these individuals are children, many travelling alone or in groups, in a desperate pursuit for sanctuary, but often falling into the clutches of people traffickers.4

Globally, Afghanistan and Syria remain the largest sources of refugees, followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan.5 All these countries are located in the Great Lakes region of Africa, an area that has been plagued by conflict, resulting in a long-standing refugee crisis that impacts other African regions, southern Africa included. In mid-2014, Sub-Saharan Africa’s refugee population was approximately 3.4 million people.6 The largest and longest-existing refugee population in the region is from Somalia; recent outbreaks of conflict in Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan triggered increases in the numbers of refugees moving within the Africa continent. Tens of thousands of these new refugees have sought asylum in countries with already large refugee populations, among them Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya and Zambia.7 It is interesting to note that four of the top ten refugee-hosting countries are in Sub-Saharan Africa, the region also hosts Dadaab, the world’s largest refugee camp established in Garrissa County, Kenya, in 1991.8

It is the responsibility of states to protect citizens from human rights violations. When they are unwilling or unable to, their citizens are forced to leave their homes to seek safety in other countries. In such instances, UNHCR takes the lead in coordinating international efforts to address the plights of refugees and others of concern to its work.9 People flee their home countries because their lives and security are threatened, and their basic human rights are at risk of being violated. Whether they are subjected to individual harassment or targeted as members of an identifiable group, many individuals are compelled to leave familiar surroundings in search of safety and stability elsewhere.10

According to the 1951 United Nations (UN) Convention on the Status of Refugees, a refugee is a person who, ‘owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership to a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or unwilling to return to it’.11

In addition to the elements of the 1951 convention and its 1967 protocol, the 1969 Organisation of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems explains that the term ‘refugee’ shall also apply to every person who, owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his or her country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave his or her place of habitual residence in order to seek refuge in another place outside his or her country of origin or nationality.12 Furthermore, the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees states that a refugee is a person who has fled his or her country of origin because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalised violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.13

The development of refugee policy in southern Africa

Countries in the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) have for a long time hosted large numbers of refugees from other nations in the region, as well as from other regional economic communities (RECs) of Africa.

Forcible population displacement into the region is known to have taken place even in pre-colonial and colonial times.14 In modern times, this phenomenon may be traced back to the early 1960s when wars of liberation from colonial rule in Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe forced thousands of people from these countries into neighbouring nations, and beyond. Asylum and refugee polices in southern Africa have gone through three generations.15 First generation refugee policies were characterised by the absence of refugee-specific laws, with refugee matters being addressed under general immigration laws. This approach was adopted during the colonial period, but it continued in some countries even thereafter. Second generation refugee policies were marked by the introduction of refugee-specific laws, but ones which were mainly intended to control rather than protect refugees. This approach was dominant throughout the 1970s and 80s. Despite patently refugee-unfriendly legislation, however, practice in the region during this period was generous. Third generation asylum and refugee policies were launched in the 1980s, and were characterised by the introduction of protection-oriented refugee legislation which approximated the provisions of international instruments on refugees. Currently, most countries in the region have comparable refugee protection statutes that incorporate the basic principles of a sound refugee regime, including provisions on the definition of refugees that are in line with international instruments, institutions and procedures for the determination of refugee status, non-refoulement and standards of treatment.16

Examining ‘durable’ solutions to refugee crises

Currently, there is no precise definition of durable solutions to the ever-increasing refugee crisis. Furthermore, the primary international instrument regulating refugees – the UN convention on refugees – does not contain any clear explanation of what constitutes a durable solution. Some scholars, however, explain that a durable solution is one where a refugee achieves a safe and sustainable result through one of three channels: voluntary repatriation, local integration and resettlement.17

Voluntary repatriation is the return in safety and dignity of a refugee to his or her country of origin, based on their free and informed decision. When prevailing conditions allow such return, repatriation is considered the most beneficial solution. It enables refugees to resume their lives in familiar settings and under the protection of their home countries.18 Repatriation is the most frequently employed solution to situations of forced displacement, primarily because of its durability. Repatriation is used as a tool for the stabilisation of post-conflict countries. Beyond reasons of political stability, according to some, the reintroduction of previously displaced populations enhances family unity and the national identity of returning refugees.19

Local integration in the refugee context is the end product of a multi-faceted and on-going process, of which self-reliance is but one part. Local integration requires preparedness on the part of refugees to adapt to host societies, without having to forego their own cultural identities. From the host societies, it requires communities that are welcoming and responsive to refugees, and public institutions that are able to meet the needs of diverse populations. Local integration has three inter-related and specific elements.

- The legal element requires that refugees are granted a progressively wider range of rights and entitlements by the country of asylum. Rights and entitlements include the right to seek employment, engage in other income-generating activities, own and dispose of property, enjoy freedom of movement and access public services – all these eventually leading to permanent residence rights.20

- The economic element expects that refugees will attain a degree of self-reliance, establish sustainable livelihoods and become progressively less reliant on state aid or humanitarian assistance.21 However, refugees who are prevented or deterred from participating in the local economy and whose standard of living is consistently lower than the poorest members of the host community cannot be considered for local integration.22

- The socio-cultural element requires that refugees are able to live amongst or alongside the host population, without discrimination or exploitation, and contribute actively to the social lives of their countries of asylum. It emphasises social relationships, including intermarriages and participation in gatherings with local communities, as well refugees’ rate of interactions in economic and social spheres.23 In instances where neither local integration nor voluntary repatriation are possible, resettlement in a third country is the alternative channel recommended by the UNHCR to resolve refugee crises. Resettlement is defined as the transfer of refugees from a state in which they have initially sought protection to a third state that has agreed to admit them with permanent residence status.24

Angolan refugees in Zambia

The Government of Zambia has a long history of welcoming refugees fleeing political and civil strife in other Sub-Saharan African countries. is is one way that the government has demonstrated its commitment to sharing the international responsibility for the protection of refugees.

The end of Angola’s civil war in 2002 marked the conclusion of more than 40 years of armed conflict that began with the war of independence from Portugal (1961–75), which was immediately followed by civil war (1975–2002). Armed conflict, insecurity and human rights abuses during the independence struggle, and the ensuing civil strife, uprooted significant numbers of Angolans. Over four million Angolans were displaced internally, while another 600000 fled the country to seek refuge in other countries, including Zambia.25

Angolan refugees have been able to access asylum status in Zambia since 1966. On 30 June 2012, however, the Government of Zambia invoked the Cessation Clause, and Angolan refugees lost their refugee status, compelling the repatriation of many people back to Angola. As repatriation was intensified, some former Angolan refugees expressed a wish to stay remain and integrate in Zambia. A large number of Angolan refugees are long-term residents of the country, with established family ties with Zambian nationals. Refugees may be unwilling to voluntarily repatriate, due to having experienced acute trauma in their country of origin or having achieved a considerable degree of socio-economic integration in the host country that they are unwilling to give up.26

Considering that not all former Angolan refugees would be willingly repatriated, in April 2014 the Zambian government and UNHCR launched the Strategic Framework for the Local Integration of Former Refugees in Zambia; the plan sought to integrate up to 10 000 former Angolan refugees into Zambian society. Beneficiaries were from two refugee settlements: Mayukwayukwa and Meheba. Implementation of the framework falls under the Office for the Commissioner for Refugees, in the Ministry of Home Affairs.27

Local integration of Angolan refugees in Zambia

The principle of local integration is firmly established in international refugee law. It has, however, continued to be a forgotten or underutilised solution to refugee crises in Africa and globally.28 Arguably, local integration has the potential to promote economic development in refugee-hosting communities, protect refugee rights and provide long-term solutions to protracted refugee situations.

Zambia is among the few African countries to offer local integration as an option for refugees.29 The country is seen as a pioneer of ‘durable solutions’ in southern Africa, where the management of refugees is still plagued by a number of shortcomings and difficulties, among them scarcity of economic opportunities for refugees and concerns for the security and stability of the SADC region30 Since its independence from British rule in 1964, Zambia has not experienced war, in contrast to many of its neighbours. However, Zambia has been affected by regional instabilities in different ways, including large flows of refugees, notably from Angola, Burundi, DRC, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Somalia and Sudan. In February 2014, Zambia was host to 22 962 refugees from Angola, 18 803 from the DRC, 6068 from Rwanda and 2 514 from Burundi.31

The Government of Zambia and UNHCR-launched Strategic Framework for the Local Integration of Former Refugees was intended to run from 2014 to 2015, with the objective of outlining priority requirements and actions, as well as resources required to implement the government’s pledge to locally integrate 10 000 refugees originating from Angola. The Refugee Control Act of Zambia (1970) restricts refugees’ enjoyment of some rights, including freedom of movement, right to employment, right to education and other basic rights, on the basis of their refugee status.32 The local integration framework sought to address these and other challenges faced by refugees that ultimately impact on their wellbeing. Furthermore, it aimed to ensure that refugees who met the criteria for local integration were progressively less dependent on humanitarian assistance as they became full Zambian citizens.

The objectives of the Strategic Framework for the Local Integration of Former Refugees in Zambia were to:

- facilitate legal integration of eligible former refugees through the issuance of long-term residence permits and country-of-origin identity documents and passports

- ensure that former refugees and their Zambian hosts settling in two designated settlements had access to demarcated land and basic services such as education and health

- advocate for additional community-based assistance to refugee-affected areas.33

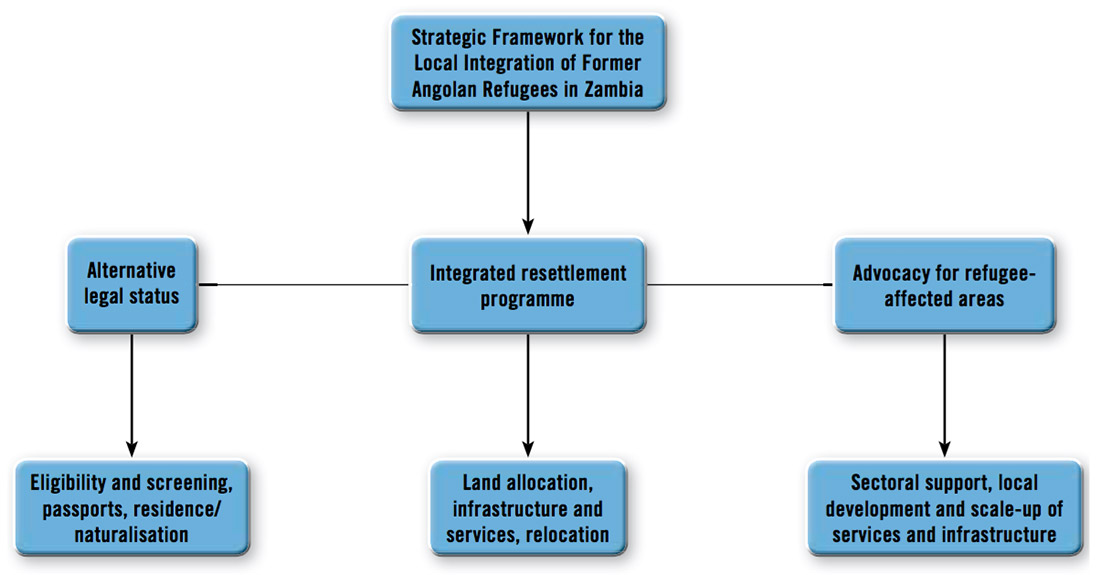

To achieve these objectives, an overall budget of US$21 million was required.34 The funding was intended to cover the following: ensuring attainment of legal status (screening of eligible former refugees, and issuing Angolan identity cards and passports that form part of the requirements), an integrated resettlement programme (involving land demarcation and allocation, infrastructure and services development and actual relocation of former refugees and eligible Zambians), and advocacy for refugee-affected areas. The diagram below illustrates the structure of the local integration programme.

Socially and economically, former Angolan refugees are successfully integrated into Zambian society.35 However, not much has been achieved in terms of legal integration, bearing in mind that the initial period of the initiative (2014–15) has elapsed. Furthermore, the success of the programme was predicated on the quick provision of Angolan identity cards and passports by the Government of Angola, and had incorporated this aspect as an integral facet to ensuring successful legal integration in a timely manner. On the contrary, however, the pace of issuing these important documents was been slow, leading to delays in achieving the aims of the framework by the Government of Zambia, through the relevant ministry, and its partners.

To date, Zambia has screened and certified approximately 6 000 Angolan refugees for eligibility for local integration.36 Out of this number, however, only 200 have been issued with immigration permits to permanently live in Zambia. Firstly, this is because the process of issuing permits for former refugees is a lengthy one. It starts with application, then the Government of Angola needs to issue the applicant with a passport, before Zambia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs can award permits to those who meet the requirements. Secondly, there are inconsistencies in the Angolan government’s processes of issuing national identity documents and passports to former refugees, which presents another bottleneck to successful implementation of the local integration process.

In many ways, former Angolan refugees have become integrated economically and are self-reliant. The main sources of livelihoods for former Angolan refugees in Zambia, deemed to support successful integration, include farming, small-scale business and casual labour. The majority of former Angolan refugees ventured into agricultural activities, notably in the production of maize, cassava, finger millet, groundnuts, beans, sorghum and other food crops when they settled in Zambia.37 Economic integration of refugees is one of the most crucial components of the process of local integration as it leads to self-reliance, a concept which explores individuals’ abilities to provide for their own needs, and hinges on their ability to enjoy freedom of movement in host countries.38

The rights of refugees are principally set out in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Furthermore, refugees are equally protected by the rights of all human beings, which are set out in a number of other declarations, such as the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESRC).39 The first right to be explored in this document – freedom of movement – is the entitlement that, above all others, has the most pronounced impact on the lives of refugees. This right is also echoed with specific regard to Africa in Article 12(1) of the 1981 African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights, which grants freedom of movement and residence to every individual within the borders of a state provided he/she abides by its laws.40

Full realisation of local integration of former Angolan refugees calls for access to education and other social services that also form a critical part of one’s development. Legal integration can enhance access to such social services as education and health. A number of declarations demand that contracting parties provide social services to refugees which are commensurate to the nationals of those countries. For example, in Article 28 of the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, signatories bind themselves to fulfil their obligation of providing education to all children, whether refugees or not.41

Socially, former Angolan refugees are fully integrated with Zambians as they attend school, church and other gatherings with each other, they play sports and celebrate holidays together and a significant number of intermarriages have been recorded.42 In both of the existing refugee settlements – Mayukwayukwa and Meheba – Angolans and Zambians who live side-by-side share cultural, ethnic and linguistic ties. Even though former Angolan refugees have socially integrated into Zambian society, it is still important to strengthen measures aimed at ensuring that no tensions arise between locals and former refugees in accessing resources.43

Recommendations

The Government of Zambia must:

- Consider extending the period for the implementation of local integration processes to ensure that the targeted number of eligible former Angolan refugees receive residence permits to reside in Zambia. Since the inception of the local integration framework in 2014, only 200 former Angolan refugees have been issued with residence permits, out of a total of 6000 certified eligible.

- Contemplate corroborating with its partners to provide expanded agricultural extension services in the rst few years of the local refugee integration programme, since most former Angolan refugees depend on agricultural activities for their survival. Consideration should also be given to the fact that refugees have the potential to enhance economic development in their communities.

- Enhance the capacity of the Office of the Commissioner for Refugees in the Ministry of Home Affairs to effectively manage the local integration programme and, in general, refugee affairs in the country.

- Engage the Government of Angola to fast-track the issuing of refugees’ country-of-origin identity documents and passports to enhance the process of legal integration and the Zambian government’s awarding of residency permits.

- Consider expanding the mandate of its National Human Rights Commission to include refugee rights in its monitoring and research functions.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees must:

- Intensify the mobilisation of resources from donors for the implementation of local integration processes, particularly in the area of legal integration, and to support Zambians in refugee-hosting communities.

- Enhance the promotion of local integration in other countries of asylum by encouraging host governments to recognise local integration as a sustainable solution to refugee crises.

Conclusion

The gap between the concept of local integration and its implementation is still significant, particularly in legal element terms. Zambia has not met the targets set out in the local integration framework, in part due to challenges with the Government of Angola and former refugees themselves, in terms of facilitating, applying for and acquiring Angolan identification documents and passports as the first step to applying for residency in Zambia. In general, the efforts of the Zambian government and UNHCR must be commended as they have led to Angolans becoming well integrated into their host communities both socially and economically since the first wave of Angolans arrived in the country in 1966. The realisation of both social and economic integration can be attributed to the shared cultural, ethnic and linguistic ties, but also to the welcoming nature of Zambians toward refugees.

Endnotes

- The author wishes to acknowledge Professor Owen Sichone and Ms Mpangi Kwenge for their invaluable contributions and constructive criticism. Appreciation is also extended to Ms Petronella Mugoni and Senzwesihle Ngubane at the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) for their support in getting this brief to the stage where it could be published.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. Strategic framework for the local integration of former refugees in Zambia.

- Phillips, S. 2011. Asylum seekers and refugees: What are the facts? Parliament of Australia. Available from: <http://www.aph.gov.au/binaries/library/pubs/bn/sp/asylumfacts.pdf> [Accessed 7 March 2016].

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. Global forced displacement tops 50 million for first time in post-World War II era. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/53a155bc6.html> [Accessed 7 March 2016].

- Amnesty International. 2015. The global refugee crisis: A conspiracy of neglect. Amnesty International. Available from: <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol40/1796/2015/en/> [Accessed 12 April 2016].

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. UNHCR mid-year trends 2014. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://unhcr.org/54aa91d89.html> [Accessed 12 April 2016].

- Amnesty International. 2015. p. 24. Op cit.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2013. UNHCR global trends 2013. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/5399a14f9.html> [Accessed 2 March 2016].

- Jastram, K. and Achiron, M. 2001. Refugee protection. International Refugee Law. Available from: <http://www.ipu.org/pdf/publications/refugee_en.pdf> [Accessed 15 November].

- Australia Department of Immigration and Citizenship. 2009. Refugee and humanitarian Issues: Australia’s response. Government of Australia. Available from: <https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/01_2014/refugee-humanitarian-issues-june09_access.pdf> [Accessed 16 February 2016].

- United Nations. 1951. Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. United Nations. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html> [Accessed 15 November 2015].

- Organisation of African Unity. 1969. OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. Organisation of African Unity. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/45dc1a682.html> [Accessed 21 December 2015].

- Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central. America, Mexico and Panama. 1984. Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America, Mexico and Panama. Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central. America, Mexico and Panama. Available from: <https://www.oas.org/dil/1984_Cartagena_Declaration_on_Refugees.pdf> [Accessed 5 March 2016].

- Rutinwa, B. no date. Asylum and refugee policies in southern Africa: A historical perspective. Southern African Regional Poverty Network. Available from: <http://sarpn.org/documents/d0001212/rutinwa/rutinwa.pdf> [Accessed 21 December 2015].

- Ibid. p. 50.

- Ibid. p. 51.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. Strategic framework for the local integration of former refugees in Zambia. Op. cit.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2011. UNHCR resettlement handbook. Division of International Protection. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/46f7c0ee2.pdf> [Accessed 16 February 2016].

- Hansen, F., Mutabaraka, J.J. and Ubricao, P. 2008. Repatriation, Resettlement, Integration: A study of the three refugee solutions. The Niapele Project. Available from: <http://www.theniapeleproject.org/files/Niapele-ScPo-Study2008.pdf> [Accessed 24 February 2016].

- Costa, D. 2006. Rights of refugees in the context of integration: Legal standards and recommendations. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/44bb90882.pdf> [Accessed 21 April 2016].

- Meyer, S. 2008. Research guide on local integration. Forced Migration Online. Available from: <http://www.forcedmigration.org/research-resources/expert-guides/local-integration/fmo045.pdf/view> [Accessed 21 April 2016].

- Crisp, J. 2004. The local integration and local settlement of refugees: A conceptual and historical analysis. New Issues in Refugee Research, Working Paper 102. Available from: <http://www.supportunhcr.org/407d3b762.pdf> [Accessed 16 February 2016].

- Bakewell, O. 2000. Repatriation and self-settled refugees in Zambia: Bringing solutions to the wrong problems. Journal of Refugee Studies 13 (4), pp. 356–373.

- Van Selm, J. 2004. The strategic use of resettlement. Journal of Refuge Studies 22 (1), p. 40.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2012. Implementation of the comprehensive strategy for the Angolan refugee situation, including UNHCR’s recommendations on the applicability of the ‘ceased circumstances’ cessation clauses. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4f3395972.pdf> [Accessed 21 April 2016].

- Ibid. p. 35.

- Ministry of Home Affairs. 2014. Commissioner for Refugees. Government of Zambia. Available from: <http://www.homeaffairs.gov.zm/?q=commission_for_refugees> [Accessed 21 December 2015].

- Fielden, A. 2008. Local integration: An under-reported solution to protracted refugee situations. Research Paper 58, New Issues in Refugee Research. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available from: <http://www.unhcr.org/486cc99f2.pdf> [Accessed 22 April 2016].

- World Bank Group. 2015. Forced displacement in the Great Lakes region. Washington, D.C. Available from: <http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2015/04/14/000333037_20150414083814/Rendered/PDF/945630REVISED000FINAL0web000revised.pdf> [Accessed 16 February 2016].

- Ibid. p. 31

- Ibid.

- Republic of Zambia. 1970. Refugee Control Act. Republic of Zambia. Lusaka, Republic of Zambia.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2012. Implementation of the comprehensive strategy for the Angolan refugee situation, including UNHCR’s recommendations on the applicability of the ‘ceased circumstances’ cessation clauses. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. p. 11. Available from: <http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4f3395972.pdf> [Accessed 21 February 2016].

- Lo Castro, L. 2015. Joint Japan-GRZ-UNHCR funding: Speech by UNHCR representative. Lusaka Voice, 26 March. Available from: <http://lusakavoice.com/2015/03/26/joint-japan-grz-unhcr-funding-speech-by-unhcr-representative/> [Accessed 21 February 2016].

- Development and Training Services. 2014. Field evaluation of local integration of former refugees in Zambia: Field visit report. Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration. Available from: <http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/235057.pdf> [Accessed 13 February 2016].

- Omers, J. 2015. Cessation of Rwandan refugee status: Two years on. Pambazuka. Available from: <http://www.pambazuka.org/human-security/cessation-rwandan-refugee-status-two-years> [Accessed 21 February 2016].

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees magazine. 2013. Zambia: Over 50 Years of Hosting Refugees. Lusaka.

- Hunter, M. 2009. The Failure of Self-Reliance in Refugee Settlements. POLIS Journal Vol. 2.

- United Nations. 1966. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. United Nations. Available from: <http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx> [Accessed 25 April 2016].

- Human Rights Education Associates. 2003. Freedom of movement. Human Rights Education Associates. Middleburg, Human Rights Education Associates.

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations. Available from: <http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx.> [Accessed 25 April 2016].

- Development and Training Services. p. 35. Op cit.

- Ibid.