Introduction

Violent conflicts affect women, men, boys, girls, the young, the old and those from particular ethnic or religious groups in different ways. Gender, age and culture may influence the type of risk someone is vulnerable to, as well as their role in the conflict. These factors may also affect their coping mechanisms, their specific needs during post-conflict recovery and their roles in building peace. Peacekeeping and peacebuilding efforts thus have a better chance of being effective if they are sensitive to these diversity issues.1 The ultimate goal of all peace efforts is a lasting, sustainable peace, and the use of a gender perspective represents a means to this end. Over the years, many policy frameworks globally, and particularly in Africa, have echoed and reflected a critical normative shift towards greater gender parity in peace processes.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) also emphasises the involvement of all genders and, more particularly, the critical importance of women’s participation in political processes, including in times of peace and conflict and at all stages of political transitions. In 2000, the UNSC adopted the ground-breaking Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (UNSCR 1325) – the first resolution to link women’s experiences of conflict to the international peace and security agenda. It focuses on the disproportionate impact of conflict on women, and calls for their engagement in conflict resolution and peacebuilding. The year 2015 marks the 15th anniversary of UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security. In preparation for the 2015 United Nations (UN) High-level Review, the Secretary-General has commissioned a global study on the implementation of UNSCR 13252 to highlight examples of good practice, implementation gaps and challenges, and priorities for action.

The Training for Peace (TfP) in Africa Programme3 seeks to build capacities to support multidimensional peace operations in Africa through training, policy support, applied research, and recruitment and rostering. One of the primary objectives of the TfP Programme is supporting and contributing to gender mainstreaming in Africa’s peace operations. This objective specifically aims to support the development of policies targeted at implementing UNSCR 1325, UNSCR 18204 and other normative developments relevant to cross-cutting issues involving women in peace and security, and strengthen the recruitment and training of female peacekeeping personnel (and trainers) for peace operations, in line with UNSCR 1325. This article5 focuses on how TfP has contributed to the efforts of gender mainstreaming in Africa’s peace operations in conflict and post-conflict situations. It also highlights the opportunities for TfP to further strengthen gender mainstreaming in Africa’s peace operations.

The Complexities of Gender Mainstreaming in Africa’s Peace Operations

Peacekeepers work in difficult circumstances where challenges such as gender-based violence, culture specific gender roles and unequal power relations between peacekeeping personnel and the civilian population have to be addressed adequately. For peacekeepers to fulfil their mandates and to respond to these challenges, the integration of a gender perspective in all spheres of peacekeeping missions is essential. Numerous international documents have been prepared, and treaties and statements passed, to support the existing UN and African Union (AU) frameworks for strengthening gender in peace operations.6 However, within the African context, these mechanisms and frameworks, coupled with the numerous regional and national frameworks for integrating gender in peace and security, create more complications in mainstreaming gender in peace processes. Different regional organisations and member states apply different laws and processes to integrating gender in their peacekeeping processes that are unique to their context. Thus, the application of international frameworks such as UNSC resolutions, international humanitarian law, and protocols and conventions on women, peace and security further add to the coordination challenges among actors and processes. This has led to the slow implementation of UNSCR 1325 in Africa. Further, member states have the primary responsibility for implementing UNSCR 1325 and related resolutions. The provision of competent troops and personnel, experts on gender, women in the armed forces and female candidates for leading positions in operations depends entirely on national decisions.7 These national decisions are based on national laws and frameworks, which are often largely masculine in priority and character.

While there are many provisions for gender mainstreaming in Africa’s peace operations, these have mostly remained as strategies on paper, lacking the requisite political will and financial support for them to be translated into action for impact. Globally, 35 countries have developed and launched national action plans (NAP), with nine of these countries in Africa.8 Several other countries have committed to developing NAPs. The NAPs developed and launched have faced challenges of funding and coordination that have greatly impeded their effective implementation. Further, there are over 2 500 indicators on women, peace and security, collated by UN Women into 400 groupings and categorised according to the four pillars9 of UNSCR 1325.10 With this many indicators, it is challenging to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the resolutions and frameworks – more so in Africa, where there are many competing interventions and actors on women, peace and security. Thus, the reach and impact of gender-related initiatives are not well documented. Over the years, TfP has strengthened its support to respond to these implementation gaps of UNSCR 1325 through its various programme initiatives and research, reflected in this article.

Gender Training for Effective and Sustainable Peacekeeping

Given the dynamic nature of peacekeeping and the unique challenges that peacekeeping personnel face on a daily basis, there is a need to ensure that they are adequately equipped with the knowledge, skills and attitudes required to perform their duties. Training is therefore important, to ensure that peacekeepers are adequately prepared with the requisite knowledge and skills to perform their mandated tasks in missions.11 Training, education and scenario-based exercises in peacekeeping form part of the many factors that determine the success or failure of peace operations. Despite the predominance of women in crisis spots, peacekeepers are seldom trained in gender issues. More often, the integration of gender training in national and regional training curricula in support of peace support operations is ad hoc. Both male and female peacekeepers need to acquire basic knowledge and a conceptual understanding of gender and security issues specific to the host nation, so that they can support the implementation of the mission mandate effectively. Gender training thus addresses the gap between the goal of gender equality and the standard practices of peacekeeping. Gender training has further sought to draw the attention of peacekeepers to the complex impact of conflict on the lives of women and girls, and of the need to engage them as agents of change in post-conflict peacebuilding processes.12 The TfP Programme focuses on providing training support in responding to these gender training gaps and the challenges faced by peacekeepers.

Balanced Gender Considerations in Training

The idea of gender promotion in peacekeeping is often directly associated with the presence of female peacekeepers in peace missions. In fact, recognising that mixed operations – made up of women and men – could have a positive impact in conflict resolution represents the first step towards gender awareness within peacekeeping operations. Since its establishment 20 years ago, TfP has supported the women, peace and security agenda in Africa through advocating for fair gender representation in training. These efforts seek to ensure that balanced gender considerations influence the selection of the personnel who go for peacekeeping training, and who are expected to serve in missions. An effective way to promote gender mainstreaming in peacekeeping missions is to integrate a gender perspective into peacekeeping selection and training. This approach of engendering the selection process provides for a qualified team with fair balance between male and female personnel to support gender considerations in the mission area. These considerations include issues of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), where most survivors are women and girls. Mission experience has shown that in Africa, these female survivors of sexual violence relate better to female peacekeepers. TfP partners have worked with the UN, AU and regional and national training institutions in Africa to increase the number of women who attend peacekeeping-related courses. Drawing from TfP partners’ experiences, the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) has made efforts to bridge the gender gap since its inception in 2003 by ensuring that academics, experts, policy-makers, practitioners, national security institutions, peacekeepers and civil society organisations in Africa are equipped with the knowledge and tools that enable effective gender mainstreaming. From 2003 to 2014, the KAIPTC trained about 12 045 participants (3 116 being women) on topical security issues that include gender, peace and security across Africa.13

Gendered Training

Incorporating a gender perspective by having gender sessions in the mainstream training undertaken by the UN, AU and regional and national training institutions enables peacekeeping personnel to better understand the social context and gender dynamics in which the operations are carried out. Gender training has been promoted as a key strategy in efforts to mainstream gender perspectives in UN peacekeeping operations.14 The UN and the AU have each placed emphasis on gender training for both civilians and uniformed peacekeepers. The training methodology adopted by the TfP Programme to support the UN and AU involves mission-specific research and training needs assessments to ensure that both the needs of male and female peacekeepers and the host community are responded to by the training. The evolution of the gender training regime in peacekeeping over the past decade has also seen the development of specialist modules to guide the in-depth training of personnel working in different components of peacekeeping missions.15 Further, as the complexity of roles and responsibilities of peacekeepers in peace operations have evolved, so have the tasks of the police regarding the rule of law, human rights and the protection of civilians, including women and children. These new emerging roles and responsibilities are reflected in the findings of the research undertaken by the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) on sexual and gender-based violence.16 The partners have responded to the capacity gaps arising from the increased expectations of what peacekeepers are expected to do by adjusting the content of the training to incorporate gender. This adjustment is supported by the increase in the development of training materials, packages and courses for gender mainstreaming informed by training needs assessments and police-contributing countries’ specific requirements.

On the civilian side, civil affairs has been identified as the single largest civilian component within peacekeeping operations. Civil affairs officers are well placed to identify and support men and women’s participation in both formal and informal peace efforts.17 The TfP Programme within the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) has trained civil affairs officers in UN missions such as the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) and the UN-AU mission in Darfur (UNAMID) on a spectrum of conflict management courses, ensuring that gender perspectives are integrated into the training. This was achieved by incorporating gender in the course content, case studies and scenario-based exercises, which has provided the mission personnel with the requisite skills and knowledge to apply gender perspectives in their conflict management and protection of civilians work. The programme ensures that even the peacekeeping trainers are trained on gender, so as to enhance their delivery in gender training. This is key, because many of the peacekeeping trainers are drawn from a military background and are often unfamiliar with gender issues.

Gender-specific Training

The TfP Programme has, over time, adopted approaches that respond to the gender training needs in Africa’s peace operations. To this end, the programme conducts a mix of pre-deployment, in-mission and specialised trainings on gender, CRSV, sexual exploitation and abuse, to name a few. TfP/ACCORD has trained on gender and the protection of women and girls in peace operations, targeting civilian, police and military personnel. A recent example of this is the ACCORD-AU mission in Somalia (AMISOM) joint training, which targeted officers from the Federal Government of Somalia and strengthened participants’ capacities to respond to the protection of civilians and gender issues in armed conflict in Somalia.

UNSCR 1325 recognises and emphasises the critical role that member states play in employing a gender dimension in peacekeeping.18 Police pre-deployment training is one of the approaches TfP has adopted in supporting member states to realise this objective. The engagement of the Norwegian National Police Directorate (POD) as a supporting partner to TfP has focused on giving more female police officers opportunities to serve in peacekeeping missions. In the past, female officers found that the required driving skills, necessary before being deployed into missions, were very challenging to attain. POD thus supported driving courses in several African countries, including Ghana – which now continues to conduct its own driving courses for female police officers, following the joint training programme with POD.

Driving courses for female police officers have also been conducted in Kenya and Malawi. At the time of writing this article, the Malawi Police Force had 59 female police officers ready for deployment. Other initiatives include the Gender and Child Course for Peacekeepers and the Gender, Child and Vulnerable Persons Protection Course, both developed and run by the Institute for Security Studies (ISS). The POD and the ISS also conducted an Integrated Gender and Sexual Gender-based Violence (SGBV) Course in 2014, with 71% female participation.19

Ending Sexual Violence in Africa’s High-intensity Conflict Environments

In war and conflict situations, sexual violence is a uniquely destructive act and method of war that poses a grave threat to international peace and security.20 These adverse effects of sexual violence have been brought to the fore by high-level UN voices. The UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Zainab Hawa Bangura, noted: “Sexual violence in conflict needs to be treated as the war crime that it is; it can no longer be treated as an unfortunate collateral damage of war.”21 The commitment of the UN, AU and other actors in preventing sexual violence in conflict has also informed TfP’s support in developing policies and interventions to respond to the sexual-related security needs of such vulnerable groups in conflict.

Policy Support

The development of UNSCR 1325 NAPs is promoted as a practical means through which states can translate their commitments into action in both domestic and foreign policy on issues of gender, peace and security. Among the pillars of the NAPs is the protection of women and their rights in conflict. TfP partners thus emphasise ending CRSV and strengthening the protection of women on the continent through policy support. A gender mainstreaming strategy emphasises the importance of addressing the different impacts and opportunities that a particular programme or policy may have on women and men, ensuring that gender concerns are taken into account in programmes. This has been another entry point for the TfP Programme in supporting gender policy efforts in peacekeeping. TfP/ACCORD worked with AMISOM in 2013 to develop a gender mainstreaming strategy for integrating gender into the work of the mission. This has impacted positively in the operations of the mission through institutionalised gendered training, gender-sensitive budgeting and gendered programming.

Training

Gender and CRSV must be considered in all mediation efforts, and in the implementation of ceasefire and peace agreements. This is supported by the TfP Programme through harmonising the training standards on mission planning being undertaken by the AU. The utilisation of the training tools developed provides for the inclusion of gender and CRSV issues at the strategic level, particularly in planning for missions to be deployed under the African Standby Force (ASF) to support peace agreements. Furthermore, various training courses undertaken by the TfP Programme in gender and CRSV issues allows for increased capacity of the peacekeepers to respond to these issues in the field. All partners with a training mandate have engaged extensively on courses specifically focused on preventing CRSV.

Applied Research

TfP has carried out research and supported policy processes to address gender-specific challenges in peace operations in Africa, in areas such as gender mainstreaming, women in conflict and post-conflict settings, and sexual-based violence. NUPI has extensively researched and published policy papers, reports and peer-reviewed articles22 on countries such as Liberia, Mali and Somalia on these topics. NUPI has also carried out applied research on the implementation challenges of UNSCR 1325 in Africa’s peace operations, drawing experiences from AMISOM, the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) and the UN Organisation Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO). Similar research has been conducted by partners to examine the ways in which women peacekeepers contribute to the operational effectiveness of peace operations, and how these contributions may or may not differ from those of male peacekeepers.

Strengthening Efforts on Conduct and Discipline, and Prevention of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in Africa’s Peace Operations |

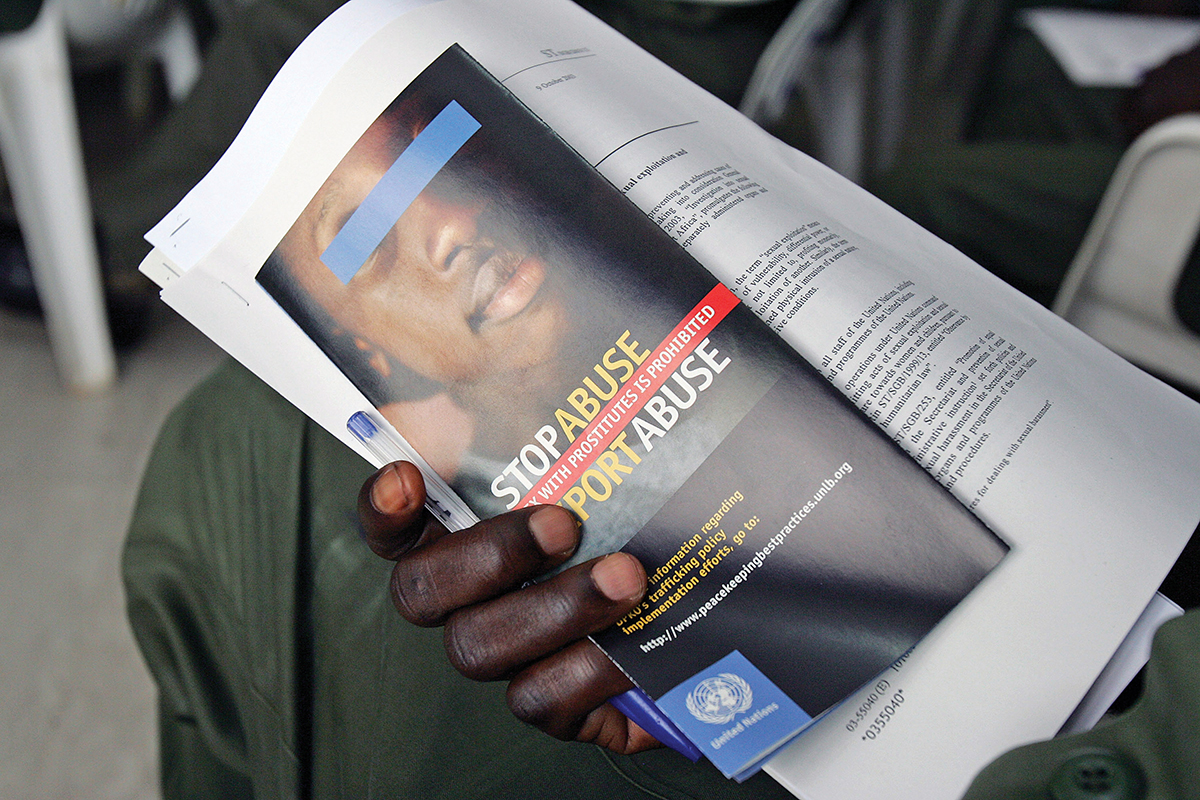

| Increasingly, missions are being deployed where there is no peace to keep and no peace agreement to defend, and where grave abuses are being committed against civilians. Among the responsibilities of peacekeepers is preventing violence, especially gender-based violence – which, in this context, refers to violence targeting women or men on the basis of their gender or sexual orientation. While carrying out their responsibilities, the peacekeepers are expected to uphold principles of good conduct and discipline and not exploit the host community, including vulnerable groups. The presence of peacekeepers has been known to increase incidents of prostitution and trafficking, exposing the host community and peacekeepers to risks associated with such vices. This has warranted the UN, the AU and other actors to develop and strengthen mechanisms and frameworks for conduct and discipline within the mission area.The engagement of the TfP Programme within ACCORD on conduct and discipline dates back to 2008, when ACCORD supported the AU in developing the concept specific to AU peace operations. This support has continued, and has expanded to include sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA). ACCORD worked with AMISOM to strengthen the capacity of its leadership in the prevention of SEA in the mission area. This led to a greater understanding of SEA issues among the leadership and uniformed and civilian personnel, who integrated and mainstreamed the provisions of the policy in their work, thus strengthening the protection of civilians by the mission. ACCORD’s most recent engagement included support to the AU in 2014 to strengthen the draft Conduct and Discipline policy framework to be used in AU peace operations.

Following research undertaken in 2011, the KAIPTC, in collaboration with TfP and the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), conducted a training course in 2013 on SEA in fragile, conflict and post-conflict situations. This training led to reduced cases of SEA in the mission area, due to a deeper understanding of the issues among peacekeepers. TfP partners have also published on issues of SEA to guide policy processes on peace operations. ACCORD’s Conflict Trends publication has featured topics on the protection of civilians and more specifically SEA, its impact on mission mandates and recent developments on the same. TfP’s gender-related research and publications have also been used extensively in training on SEA in peace operations in Africa and other regions. |

Opportunities for Engagement with the Women, Peace and Security Agenda

With the UN High-level Review taking place in October 2015, and the finalisation of the global study on UNSCR 1325, many recommendations for further strengthening the implementation of UNSCR 1325 beyond 2015 will be made. The issues of women, peace and security are also being discussed in the review of the UN peacebuilding architecture,23 as well as in the post-2015 development agenda.24 It is evident from all the reviews and assessments that the vast majority of casualties in today’s wars are women and children. Women, in particular, face devastating forms of sexual violence, which are sometimes strategically used to achieve military or political objectives.25 CRSV has often become a weapon of choice as it is cheap, silent and effective. This form of violence remains chronically under-reported, due to fear and stigmatisation. There should therefore be more qualified and trained peacekeepers and peacemakers to strengthen and facilitate communication and reporting.

UNSCR 1889 (2009) requires the UN system to collect and analyse data on the particular needs of women and girls in post-conflict situations, to improve the system-wide response to their security challenges and increase the participation of women and girls in decision-making.26 TfP and other relevant actors should therefore conduct or commission periodic research or studies on the extent and magnitude of the problem of gender mainstreaming in armed conflict. This will complement the UN’s efforts in addressing the implementation challenges of UNSCR 1325, and will also assist in increasing the level of gender statistics in conflict situations. As a post-2015 agenda item, it is also important for TfP to continue its policy support for the inclusion of women at peace negotiation tables, and highlighting women’s security as a major priority in conflict resolution. Also important is the continued emphasis and promotion of women’s participation in post-conflict reconstruction efforts, and their empowerment in development initiatives and the work of peace missions.

Noting the importance of the security and judicial sectors, there should be emphasis on awareness-raising among organs of governments and within the AU structure on the implementation of UNSCR 1325. Key partners, including TfP, should also urge governments (that have not done so) to develop and operationalise NAPs to implement UNSCR 1325, along with its accompanying resolutions.27 In addition, TfP should continue to support the implementation of existing national and regional plans, laws, policies and protocols that support men and women’s participation in peace processes at the national and regional levels. There is also a greater need for partners to engage with regional organisations on strengthening gender in peace operations.

Conclusion

Significant gaps still remain in the effective implementation of international mechanisms, and in the provision of support and services for those most vulnerable in conflict, including women. The effects of gender mainstreaming have so far been limited. To overcome the shortcomings of gender mainstreaming, an integrated framework for action is required. Gender mainstreaming practices should address both institutional and structural barriers faced by different groups of women and men in conflict settings. Therefore, gender analysis should inform all gender mainstreaming actions and other interventions in peace and security. To this end, the experts on gender must be substantially involved in designing, implementing and monitoring gender mainstreaming programmes and policies for gender analysis to be credible and relevant. The number of female peacekeepers in the current peace missions in Africa is low – it is a gap that will likely take longer than anticipated to bridge. To be able to respond to the gaps created by the low number of women in peacekeeping, male peacekeepers should be given gender sensitivity training to further strengthen their understanding of such issues, and for them to respond appropriately to the needs of survivors of sexual violence in conflict. Gender training thus serves as one of the key strategies for enhancing the knowledge and understanding of peacekeepers, to enable them to apply more gender-sensitive approaches to peacekeeping, more particularly in the prevention of sexual violence in conflict.

More concerted efforts should also be considered to further build the capacities of uniformed and civilian peacekeepers to respond to gender-specific issues in peace missions, and at a strategic level. This goes hand-in-hand with further strengthening policy processes on gender in peace operations to generate enhanced awareness and understanding of the implications of gender interventions for peace operations in Africa. Ending sexual violence is not a responsibility that governments alone can bear. There is a need for a coherent and comprehensive approach to address sexual and gender-based violence in Africa. The TfP Programme and other similar initiatives should thus support those efforts that seek to realise the objectives of the UN and AU in mainstreaming gender for effective implementation of the mission mandate.

Endnotes

- De Coning, Cedric H., Harvey, Joanna and Fearley, Lillah (2012) Civil Affairs Handbook. New York: UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations.

- UN Women (2015) ‘Preparations for the 2015 High-level Review and Global Study’, Available at: <http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-peace-security/1325-review-and-global-study> [Accessed 11 March 2015].

- TfP partners include the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC), which focuses on civilians, police and the military; the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) in Pretoria, which focuses on police; the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), which focuses on civilians; and the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), which focuses on research. The African Civilian Response Capacity for Peace Support Operations (AFDEM), which focuses on recruitment and rostering, left the TfP partnership in 2013. Supporting partners are the Eastern Africa Standby Force Coordination Mechanism (EASFCOM) and the Norwegian Police Directorate (POD), which focuses on police.

- In 2008, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1820, which explicitly links sexual violence as a tactic of war with women’s peace and security issues. This Resolution reinforces Resolution 1325 and highlights that sexual violence in conflict constitutes a war crime, and demands that parties to armed conflict immediately take appropriate measures to protect civilians from sexual violence. These measures include training troops and enforcing disciplinary measures.

- The author acknowledges the contributions of the TfP partners to this article.

- These include the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 1979, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 1995, the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) Agreed Conclusions on Gender Mainstreaming in 1997, the Security Council Presidential Statement (Bangladesh) on 8 March 2000, the Windhoek Declaration and the Namibia Plan of Action on Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multi-dimensional Peace Support Operations in May 2000, and the Outcome Document of the UN General Assembly Special Session on Women 2000: Gender Equality, Development and Peace for the 21st Century.

- Mari Skí¥re (2014) ‘Why Gender Matters: Lessons Learned from a NATO Perspective’, Available at: <http://www.Nato.Int/Cps/En/Natohq/Opinions_107906.Htm?Selectedlocale=En>.

- PeaceWomen (n.d.) ‘UN Security Council Resolution 1325 National Action Plan Initiative’, Available at: <http://www.wunrn.com/news/2012/05_12/05_14/051412_un2.htm>.

- Resolution 1325 has four ‘pillars’ that support the goals of the Resolution. These are: participation, protection, prevention, and relief and recovery.

- Kuonqui, Christopher and Cueva-Beteta, Hanny (2012) ‘Tracking Implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000)’, Available at: <http://www.unwomen.org/~/media/Headquarters/Media/Publications/en/02ATrackingImplementationofSecurityCouncilRe.pdf> [Accessed 25 March 2015].

- UN Peacekeeping Resource Hub (n.d.) ‘Peacekeeping Training’, Available at: <http://research.un.org/en/peacekeeping-community/Training>.

- Lamptey, Comfort (2012) Gender Training in United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. Gender and Peacekeeping in Africa, Occasional Series, 5.

- Statistics obtained from the KAIPTC document on the summary of the work done on gender by the KAIPTC.

- Lyytikäinen, Minna (2007) ‘Gender Training for Peacekeepers: Preliminary Overview of United Nations Peace Support Operations’, United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (UN-INSTRAW) Gender, Peace & Security Working Paper 4, Available at: <http://www.peacewomen.org/assets/file/Resources/UN/un-instraw_gendertrainingpk_2007.pdf> [Accessed 25 March 2015].

- Lamptey, Comfort (2012) op. cit.

- De Carvalho, Benjamin and Schia, Niels Nagelhus (2012) Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Liberia and the Case for a Comprehensive Approach to the Rule of Law. Journal of International Relations and Development, 14(1), pp. 134–141; and Schia, Niels Nagelhus and De Carvalho, Benjamin (2010) Nobody Gets Justice Here! Addressing Sexual and Gender-based Violence and the Rule of Law in Liberia. NUPI Report, p. 761.

- De Coning, Cedric H., Harvey, Joanna and Fearley, Lillah (2012) op cit.

- Inter-Agency Network on Women and Gender Equality (IANWGE) (n.d.) ‘National Implementation of Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000)’, Available at: <http://www.un.org/womenwatch/ianwge/taskforces/wps/national_level_impl.html> [Accessed 5 March 2015].

- Statistics obtained from POD document on the summary of the work done on gender by the POD.

- UK Government Foreign & Commonwealth Office and The Rt Hon. William Hague (2014) ‘Chair’s Summary – Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict’, Policy Paper, Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chairs-summary-global-summit-to-end-sexual-violence-in-conflict/chairs-summary-global-summit-to-end-sexual-violence-in-conflict> [Accessed 27 March 2015].

- UN (n.d.) ‘Background Information on Sexual Violence Used as a Tool of War’, Available at: <http://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/about/bgsexualviolence.shtml>.

- See, in particular, Solhjell, Randi and Gjelsvik, Ingvild M. (2014) Female Bodies and Masculine Norms: Challenging Gender Discourses and the Implementation of Resolution 1325 in Peace Operations in Africa. NUPI Report; Solhjell, Randi (2013) Countering ‘Malestreaming’: Integrating the Gender, Peace and Security Agenda in Peace Operations in Africa. NUPI Policy Brief, 22; Solhjell, Randi (2013) Gender Perspectives in UN Peacekeeping Innovations? The Case of MONUSCO in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. NUPI Policy Brief, 19; and Gjelsvik, Ingvild Magní¦s (2013) Women, Peace and Security in Somalia: A Study of AMISOM. NUPI Policy Brief, 16. The publications can be accessed freely through NUPI’s webpage (<www.nupi.no>) and at <http://english.nupi.no/Activities/Programmes2/Training-for-Peace> and <http://trainingforpeace.org/publications/>.

- UN Women (2015) ‘Women, Peace and Security: Seeking Synergy with the Reviews on Peace Operations and Peacebuilding’, Available at: <http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2015/01/women-peace-and-security-seeking-synergy-with-the-reviews-on-peace-operations-and-peacebuilding#sthash.MwJQl1Ak.dpuf>.

- UN (2015) ‘High-level Thematic Debate on Advancing Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women and Girls for a Transformative Post-2015 Development Agenda’, Available at: <http://www.un.org/pga/060315_hltd-gender-equality-empowerment-women-girls-transformative-post-2015-agenda/>.

- UN (n.d.) ‘Background Information on Sexual Violence Used as a Tool of War’, op. cit.

- UNSCR 1889 (2009). More about this resolution can be found at: <http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/issues/women/wps.shtml>.

- UNSCR 1820 (2008), 1888 (2009), 1889 (2009), 1960 (2010), 2106 (2013) and 2122 (2013). More about these resolutions can be found at: <http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/issues/women/wps.shtml>.