Peacebuilding is about influencing the behaviour of social systems that have been, or are at risk of, being affected by violent conflict. A society sustains peace when its social institutions are able to ensure that political competition is managed peacefully, and that no significant social or political groups use violence to pursue their interests. Peacebuilding attempts to assist societies to prevent and mitigate the risk of violent conflict. For peace to be self-sustainable, a society needs to have sufficiently strong social institutions to identify, channel and manage disputes peacefully.

If a society is fragile, it means that the social institutions that govern its politics, security, justice and economy lack resilience. Resilience refers to the capacity of social institutions to adapt in order to sustain an acceptable level of function, structure and identity under stress. The fragility or vulnerability is gradually reduced as social institutions develop the resilience – the internal complexity that enables them to self-organise – necessary to cope with the shocks and challenges to which they are exposed. Resilience to withstand shocks and challenges, and the ability to adapt, grows as social institutions develop increasingly complex forms of self-organisation. For example, in 1991 in South Africa, some churches and a private sector group managed to facilitate a national peace accord, which significantly reduced political violence. The National Peace Accord was an important adaptation that moved the country from relying on the state security apparatus, which was no longer credible or effective, and instead empowered social institutions to self-manage the tensions that arose between communities divided by apartheid. This is one example of how the resilience of civil society in South Africa played an important role in helping the country navigate the very sensitive transfer of power relatively peacefully.

Peacebuilding is thus a project with a very specific objective: to influence complex social systems to safeguard, stimulate, facilitate and create the space for societies to develop resilient self-organised social institutions that can prevent violent conflict and sustain the peace. Conflict resolution and peacebuilding is about stimulating processes in a society that enable self-organisation and lead to resilient social institutions which adequately manage internal and external stressors and shocks. It is not possible to direct or control self-organisation from the outside; it has to emerge from within a society. However, conflict resolution and peacebuilding agents can assist society by facilitating and stimulating the processes that enable self-organisation to emerge.

Peacebuilding and self-organisation

There is an inherent tension in the act of promoting a process of self-organisation from outside the society or community in question. Too much external interference – for instance, by an international organisation such as the United Nations (UN) – will undermine self-organisation. Every time an external peacebuilder intervenes to solve a perceived problem, they interrupt the internal feedback process and thus deny the society from responding to its own stimuli. The result is a missed opportunity to contribute to the development of self-organisation and resilience, and in its place, such interruptions build dependency. Each external intervention thus comes at the cost of depriving a society from an opportunity to learn how to respond to a problem or challenge itself. State and social institutions develop resilience through trial and error over generations. Too much filtering and cushioning slows down and inhibits these processes. Understanding this tension – and the constraints it poses – helps us to realise why many international conflict resolution and peacebuilding interventions have made the mistake of interfering so much that they have ended up undermining the ability of societies to self-organise.

The adaptive peacebuilding approach provides a methodology for navigating this dilemma. It stands in contrast to externally driven, top-down, blueprint or predetermined design approaches to peacebuilding planning and assessment. Adaptive peacebuilding is a process where peacebuilders, together with the communities and people affected by the conflict, actively engage in a structured process to sustain peace and resolve conflicts by employing an iterative process of learning and adaptation.1

Adaptive Peacebuilding principles

The adaptive approach for coping with complexity in conflict resolution and peacebuilding can be summarised in the following six principles:

- The actions taken to influence the sustainability of a specific peace process have to be context and time specific, and they have to be emergent from a process that engages the societies themselves.

- Adaptive peacebuilding is a goal-orientated or problem-solving approach, so it is important to identify, together with the society in question, what the peacebuilding project should aim to achieve.

- Adaptive peacebuilding is agnostic about how best to pursue its goals, but it does follow a specific methodology – the adaptive approach – that is, a participatory process that facilitates the emergence of a goal-orientated outcome.

- A key part of the adaptive approach methodology is variety; as the outcome is uncertain, one must experiment with a variety of options across a spectrum of probabilities.

- Another key part of the adaptive approach is selection – one has to pay close attention to feedback to determine which actions have a better effect. Adaptive peacebuilding requires an active participatory decision-making process that abandons those actions which perform poorly or have negative side-effects, whilst those that show more promise can be further adapted to introduce more variety or can be scaled up to have greater impact. At a more strategic level, this implies reviewing assumptions and adapting strategic planning.

- Adaptive peacebuilding is an iterative process. It is repeated continuously because in highly complex contexts, assessments are only relevant for a relatively short period before new dynamics come into play.

In the adaptive peacebuilding approach, the core activity of a conflict resolution or peacebuilding intervention is one of process facilitation. It is thus crucial – as captured in the first principle of the adaptive peacebuilding approach – that the societies and communities which are intended to benefit from a conflict resolution or peacebuilding intervention are fully involved in all aspects of the initiative. The specific arrangements will differ depending on the context, but the principle should be that no decisions are taken about a particular conflict resolution or peacebuilding intervention without sufficient participation of the affected community or society, depending on the level and scope of the intervention. Sufficiency here implies that the community should be represented in such a way that the diversity and variety of their interests, needs and concerns inform every step of the adaptation cycle. In other words – as highlighted in the second principle of the adaptive peacebuilding approach – the affected community should be sufficiently represented in the processes that determine the aims and objectives of the initiative, as well as in all choices related to the analysis, assessment, planning, monitoring of effects, evaluation and selection processes.

While international or external peacebuilders can influence complex social systems by enabling and stimulating the processes that enable resilience and inclusiveness to emerge, the prominent role of self-organisation in complex system dynamics suggests that it is important that the affected societies and communities have the space and agency to drive their own process. This is why local adaptation processes are ultimately the critical element for inclusive political settlements to become self-sustainable.

The adaptive peacebuilding approach thus requires a commitment by peacebuilders to engage in a structured learning process, together with the society or community that has been affected by conflict. This commitment comes at a cost – in terms of investing in the capabilities necessary to enable and facilitate such a collective learning process, in taking the time to engage with communities and other stakeholders, and in making the effort to develop new innovative systems for learning together with communities as the process unfolds.

Complex systems cope with challenges posed by changes in the environment by co-evolving with the environment in a never-ending process of adaptation. This iterative adaptive process – captured in the third, fourth and fifth principles of the adaptive peacebuilding approach – utilises experimentation and feedback to generate knowledge about the environment. This is essentially the way natural selection works in the evolution of complex systems. The two key factors are variation (the fourth principle) and selection (the fifth principle). There needs to be variation – that is, multiple parallel interventions – and there needs to be a selection process that replicates and multiplies effective interventions and discontinues those that do not have the desired effect. The analysis–planning–implementation–evaluation–selection project cycle is already well established in the development and peacebuilding communities. However, most peacebuilding projects are not good at generating sufficient variation. They are also notoriously bad at selection based on effect, and they are especially poor at identifying and abandoning underperforming initiatives. To remedy these shortcomings, the adaptive peacebuilding approach utilises structured and iterative adaptation (the sixth principle) to help generate institutional learning.

The adaptive approach consists of iterative cycles of learning, starting with analysis and assessment. Based on the analysis, multiple possible options for influencing a social system are generated. For example, a peacebuilding campaign – such as the UN stabilisation strategy for the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo – may choose to undertake several interventions that have more or less the same broad aim, such as supporting the extension of state authority. When the selected options are developed into actual campaigns or programmes, their design must be explicit about the theory of change each will employ, so that their effects can be assessed. For example, such a strategy may build police stations and support the training and deployment of new police officers. The idea behind this project may be that these actions will help to ensure that the state is visibly present and active in these regions of the country, and this will then reduce conflict. A theory of change needs to indicate clearly how it intends to achieve a change in the behaviour of the social system it intends to influence – that is, how a series of activities is anticipated to generate a particular outcome. For example, how exactly will the deployment of police officers result in the expected outcome? How many police officers would be needed? What kind of actions are these police officers expected to take? How will they be supported by other parts of the state system; for instance, by the justice system? A selected number of these intervention options are then implemented and closely monitored, with a view to identify the feedback generated by the system in response to each intervention. The feedback is then analysed, after which those responsible for the intervention, together with the affected communities and key stakeholders, decide which initiatives to discontinue, which to continue and, in addition, what adaptations to introduce for those that are continued. For example, by closely monitoring such projects, one may learn that the new police officers start to charge the community for their services or expenses, if they do not receive their salaries on time and if they do not have a budget for transport or other such costs they incur when performing their duties. The project can thus be adapted to add these elements if they were not foreseen at the outset. Those initiatives that perform better may be expanded or replicated. The ineffective ones, or those that have generated negative effects, should be abandoned. Effective initiatives should be continued and expanded in a variety of ways, so that there is a continuous process of experimentation with a range of options, coupled with a continuous process of selection and refinement.

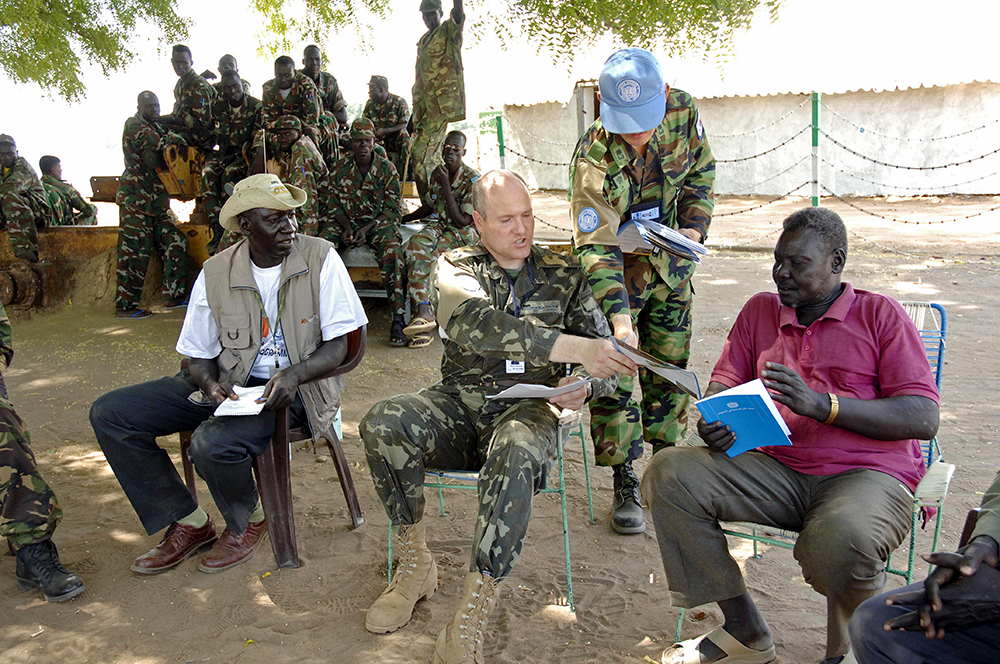

In practice, this method may not always be so explicitly employed, but the basic tenants of the adaptive approach are usually already at work in most conflict resolution and peacebuilding contexts. For example, UN peacekeeping operations in the Central African Republic and South Sudan, together with local communities, employ a range of strategies to pursue local peace agreements, improve local security, disrupt local conflict dynamics and encourage local economic activity. The people involved are continuously learning from their experiences and are adapting their approaches based on their assessment of which initiatives are more or less effective. Adaptive peacebuilding in these contexts does not necessarily imply following an explicit methodological approach. It is more a pattern of practices that experiment with an inductive, iterative and adaptive approach. These adaptive approaches differ fundamentally from the determined-design approach that was in vogue in the past, where the logic of the programmatic intervention was predetermined, and the role of the peacebuilders and communities was to implement the programmes as designed.

An adaptive peacebuilding approach recognises the role of entropy, and cultivates an awareness that those interventions which appear to be effective today will not continue to be so indefinitely. Any intervention will likely benefit some and not others. Those who do not benefit from it are likely to adapt and develop strategies to either undermine the initiative or to position themselves to benefit from it. Even successful programmes need to be monitored for signals that may indicate that an intervention is no longer having the desired effect or is starting to generate negative side-effects. One must thus not only monitor for intended results, but also for unintended consequences, and be ready to take steps to deal with the adverse effects that may come about due to an intervention.

The adaptive peacebuilding approach is scalable at all levels – the same basic method can be applied to individual programmes, to projects, to regional or national-level campaigns, or to multi-year strategic frameworks or compacts. From a complexity theory perspective, the feedback generated by various interventions at different levels should be shared and modulated as widely as possible throughout the system, so that as broad a spectrum of initiatives as possible can self-adjust and co-evolve on the basis of the information generated.

The adaptive peacebuilding approach aims to help societies build the resilience and robustness needed to cope with, and adapt to, change by developing greater levels of complexity in their social institutions. A less complex social system will have only one way to manage intercommunity conflict. A more complex social system will have a variety of mechanisms and processes to manage intercommunity conflict, depending on the type of conflict and the people involved – for example, traders, farmers or youth. The adaptive peacebuilding approach aims to work with the constructive attributes of change by investing in the resilience of social institutions to cope with and channel change positively, and to manage conflict in such a way that it does not become violent. It does so by involving local societies and communities in all decisions related to the peacebuilding process, at a scale not attempted to date.

Conclusion

Complexity theory helps us understand how social systems lapse into violent conflict, how they can prevent or recover from conflict, and what can be done to strengthen their resilience. For a peace process to become self-sustainable, resilient social institutions need to emerge from within – that is, from the local culture, history and socio-economic context. External actors can assist and facilitate this process, but if they interfere too much, they will undermine the self-organising processes necessary to sustain resilient social institutions.

The key to successful conflict resolution and peacebuilding thus lies in finding the appropriate balance between international support and local self-organisation, and this will differ from context to context. Those engaged in conflict resolution and peacebuilding should limit their efforts to safeguarding, stimulating, facilitating and creating the space for societies to develop resilient capacities for self-organisation.

Adaptive peacebuilding is an approach that can help navigate this delicate balance between international support and local self-organisation. Peacebuilders, together with the communities and people affected by the conflict, actively engage in a structured process to sustain peace by employing an iterative process of learning and adaptation. The adaptive peacebuilding approach is aimed at supporting societies to develop the resilience and robustness they need to cope with and adapt to change by developing greater levels of complexity in their social institutions.

Endnotes

- For more on Adaptive Peacebuilding see: De Coning, Cedric (2018) Adaptive Peacebuilding, International Affairs, 94(2), pp. 301–317, Available at: <https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix251>