The transition from apartheid to democracy in South Africa remains a defining global moment in history emblematic of how political compromise can transform a divided society. Central to this transformation was the establishment of the Government of National Unity (GNU), a power-sharing arrangement that functioned from 1994 to 1997. GNUs are generally formed with the aim of bringing together the broadest possible spectrum of political interests in response to a crisis. GNUs are formed to achieve national interests, such as nation-building, social order, and peace and stability.1Beukes, Jennica; Chigwata, Tinashe; and de Visser, Jaap (2024) ‘Unpacking the 2024 Government of National Unity in South Africa: Challenges, opportunities and lessons for Stable Coalition Governance’, Available at: https://dullahomarinstitute.org.za/multilevel-govt/publications/doi-policy-brief-on-gnus.pdf [Date accessed: 16 August 2024]. After a peaceful transition in 1994, South Africa was readmitted as a member of the international community of nations. This time, it was recognised as a constitutional democratic state, relinquishing its pariah status. The effort to establish South Africa’s position in international relations began earnestly, guided by its foundational values and principles, as enshrined in the Constitution.2DIRCO (2024) ‘Framework Document on SOUTH AFRICA’S NATIONAL INTEREST and its advancement in a Global Environment’, Available at: https://www.dirco.gov.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/sa_national_interest.pdf [Date accessed: 16 August 2024]. The GNU was an unprecedented act of political compromise created to address deep-rooted historical grievances, while managing the competing interests of various political actors.

Fast forward to 2024, and the political landscape in South Africa leading up to the recent elections was marked by significant shifts and uncertain developments. This is due to the rise of small parties, declining support for traditional parties, such as the African National Congress (ANC), and increasing public dissatisfaction with governance, which created an environment characterised by uncertainty and fragmentation.3Ragolane, Mahlatse (2024) ‘An investigation into the causes and impact of service delivery protests on political stability: perceptions from the social contract and relative deprivation’, EUREKA: Social and Humanities, 1, 75–88. This environment set the stage for the formation of the GNU – a coalition formation driven by the need to stabilise a fractured political environment and address deep-seated socioeconomic challenges. South Africa has now entered an era of multi-party governance across all three spheres of government.4Beukes, Jennica et al. (2024) ‘Unpacking the 2024 Government of National Unity in South Africa’, op. cit. Unlike the historic GNU of 1994, which emerged from the widespread recognition of the merits of compromise among the most significant political actors5Nupen, Dren (2004) ‘Elections, Constitutionalism and Political Stability in South Africa’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 4(2), 119–143. and the fight against injustices by ANC and other movements, the 2024 GNU was born out of electoral necessity and a fragmented electorate. This development is likely to influence changes to the existing governance framework to facilitate cooperative and stable governance across the three spheres of government.6Beukes, Jennica et al. (2024) ‘Unpacking the 2024 Government of National Unity in South Africa’, op. cit. South Africa is at a pivotal moment and needs to ensure the stabilisation of the political landscape, while simultaneously laying the foundations for peace, reconciliation and sustainable development. While the diverse perspectives within a GNU can lead to adaptive and responsive policies, the need for consensus can also result in rigid compromises that slow down the government’s ability to act swiftly in response to stability and peacebuilding.7Maleka, Mahlomola Stevens (2024) ‘The Implications of a Government of National Unity on Strategic Planning in South Africa’, Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381602366_The_Implications_of_a_Government_of_National_Unity_on_Strategic_Planning_in [Date accessed: 16 August 2024]. This article delves into the intricacies of the GNU, focusing on how political compromise can be used as a tool to balance competing interests and promote stability, peace and governance in South Africa.

The road to the 2024 elections: A fractured landscape after 30 years

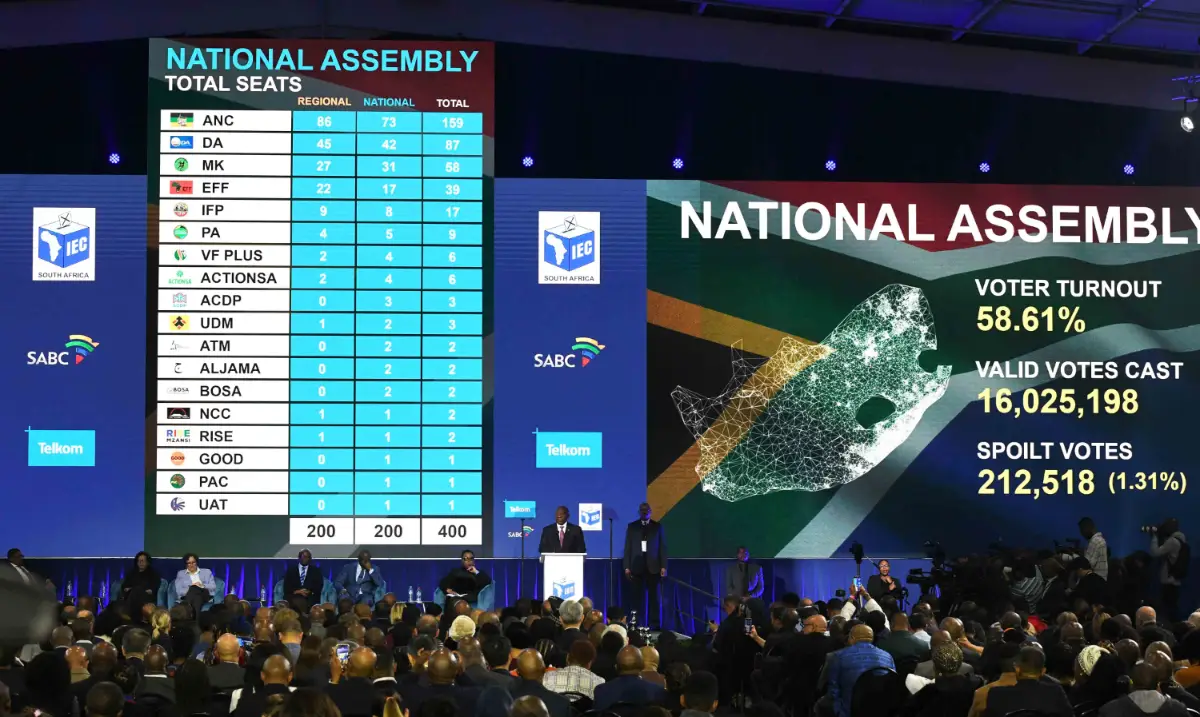

Since 1994, the South African political landscape has been dominated by the ANC, which has enjoyed electoral support in both national and provincial governments. However, this dominance has led to pessimism replacing the initial optimism. The growing dissatisfaction with the ANC’s governance, fuelled by persistent stagnation and an increase in service delivery protests in various communities across the provinces, is the reason behind this shift in sentiment. The ANC has historically had a firm grip on power, anchored in its legacy as a liberation movement and national share of the votes of 62.6% in 1994, 66.4% in 1999, 69.7% in 2004, 65.9% in 2009, 62.2% in 2014, and 57.5% in 2019. However, the 2024 election saw a different turn, with the ANC obtaining 40.18%, a decline of 17.32% from the previous election year.8Cowling, Natalie (2024) ‘African National Congress general election results in South Africa 1994-2024’, Statista, Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1402238/anc-general-election-results-in-south-africa [Date accessed: 16 August 2024]. The 2024 general election witnessed a dispersal of votes among multiple parties. The Democratic Alliance (DA) garnered 21.81% of the votes, while the uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) Party, founded by former ANC president Jacob Zuma in December 2023, obtained 14.58%. The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) secured 9% of the vote, and the remaining votes were distributed among 14 smaller parties. Among these, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), Patriotic Alliance (PA), and Vryheidsfront Plus (VF Plus, also known as the Freedom Front Plus) had the most votes. The remaining parties, in descending order by number of seats, were ActionSA, United Democratic Movement (UDM), African Christian Democratic Party, Rise Mzansi, Cape Coloured Congress (CCC), Build One South Africa (BOSA), African Transformation Movement (ATM), Al Jama-ah, Pan African Congress (PAC), GOOD party, and United Africans Transformation (UAT). This election resulted in the most diverse Parliament in South Africa’s history, including numerous small parties with limited seat shares.9Ndzendze, Bhaso and Hlabisa, Nhlakanipho (2024) ‘South Africa’s new coalition government: implications for social, economic and foreign policy’, African Policy Research Institute, 16 July, Available at: https://afripoli.org/south-africas-new-coalition-government-implications-for-social-economic-and-foreign-policy [Date accessed: 16 August 2024].

The decline in voter support for the ANC in recent years can be attributed to several interconnected issues. First and foremost, widespread dissatisfaction with persistent corruption within the party, exemplified by the state capture scandals, eroded public trust. Additionally, the ANC’s inability to address critical socioeconomic challenges, such as high unemployment rates, deepening poverty and poor service delivery, left many citizens disillusioned. The party’s internal factionalism and leadership struggles also contributed to its image as ineffective and self-serving. Furthermore, younger voters, making up 32% of the country’s unemployed (with a 45.5% unemployment rate among young individuals aged 15-34 years),10Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) (2024) ‘Unemployment in South Africa: A Youth Perspective’, Available at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=17266 [Date accessed: 20 August 2024]. are increasingly disconnected from the ANC’s liberation legacy and are seeking alternatives that better resonate with their aspirations and frustrations. Collectively, these factors have led to voter apathy and a growing belief that the ANC is no longer capable of delivering meaningful change, resulting in a significant decline in voter support for the party.

Put differently, these reasons have been attributed to what we now call the GNU. For the establishment of the GNU, the President of the ANC called for other political parties to join negotiations aimed at forming a GNU. South Africa, like many other countries, faces the threat of political instability and conflict. Unfortunately, the country still grapples with the remnants of past divisions, which are reflected in the persistent patterns of racialised poverty and inequality. To effectively address these challenges, it is imperative to maintain political stability and foster policy innovation in critical areas such as education, health, and the economy.11Steyn Kotze, Joleen (2024) ‘South Africa’s unity government: 4 crucial factors for it to work’, The Conversation, 18 June, Available at: https://theconversation.com/south-africas-unity-government-4-crucial-factors-for-it-to-work-232533 [Date accessed: 16 August 2024]. The 2024 GNU may have been formed in a time of dire socioeconomic circumstances, but it is hard to maintain that the crisis is as profound as it was in 1994.12Beukes, Jennica et al. (2024) ‘Unpacking the 2024 Government of National Unity in South Africa’, op. cit. However, the GNU, in its formation, was to ‘ensure stability and peace, tackling the triple challenges of poverty, unemployment and inequality, entrench our Constitutional democracy and the rule of law, and to build a South Africa for all its people.’13ANC (2024) ‘Statement of Intent of the 2024 Government of National Unity’, Available at: https://www.anc1912.org.za/statement-of-intent-of-the-2024-government-of-national-unity-2 [Date accessed: 16 August 2024]. The parties that joined the GNU are the ANC, DA, PA, IFP, GOOD, PAC, UDM, VF Plus, Rise Mzansi, and Al Jama-ah.14Tannur, Anders (2024) ‘Which parties make up South Africa’s unity government?’ Reuters, 24 June, Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/which-parties-make-up-south-africas-unity-government-2024-06-24 [Date accessed: 16 August 2024].

The formation of the 2024 Government of National Unity: Key compromises towards achieving peacebuilding and stability

The negotiations leading to the formation of the 2024 GNU were fraught with tensions as political parties with different ideologies and policy priorities had to find common ground. On 14 June 2024, a Statement of Intent was published highlighting the priorities the GNU will pursue in the next five years. The GNU was built on a series of key compromises that reflect the competing interests of the parties involved, each seeking to advance their agenda while contributing to national stability. The Foundational Principles of the GNU in Clause 8 of the Statement of Intent highlight the significant focus of the parties and their willingness to ensure stability and peace in the country. Clause 8 reads:

8. All parties to the GNU commit to uphold the following fundamental principles:

8.1 Respect for the Constitution, the Bill of Rights in its entirety, a united South Africa and the rule of law.

8.2 Non-racialism and non-sexism.

8.3 Social justice, redress and equity, and the alleviation of poverty.

8.4 Human dignity and the progressive realisation of socioeconomic rights.

8.5 Nation-building, social cohesion and unity in diversity.

8.6 Peace, stability and safe communities, especially for women and children.

8.7 Accountability, transparency and community participation in government.

8.8 Evidence-based policy and decision-making.

8.9 A professional, merit-based, non-partisan, developmental public service that puts people first.

8.10 Integrity, good governance and accountable leadership.15ANC (2024) ‘Statement of Intent of the 2024 Government of National Unity’, op. cit.

The GNU’s dedication to principles such as nation-building, social cohesion, unity, non-racialism and non-sexism further underscores that the GNU aims to promote inclusion and cooperation. By adhering to these principles, the GNU seeks to unite diverse political parties and cooperate to fulfil the aspirations of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution).16Beukes, Jennica et al. (2024) ‘Unpacking the 2024 Government of National Unity in South Africa’, op. cit. Further to this is the power-sharing agreement that distributes positions of power among the main political parties and ethnic groups. This ensures that all major stakeholders have a voice in the decision-making process and prevents any single group from dominating the others.17Chaka, Mpho and Adanlawo, Eyitayo Francis (2024) ‘The Role of Communication in Nation-Building: A Theoretical Framework for South African National Unity’, Studies in Media and Communication, 12(3), 325–334. Another major area of compromise involves policy concessions across key issues such as land reform, economic policy, and service delivery. These policy compromises were essential to crafting a unified government platform that could command the support of the coalition’s diverse constituencies.

Given the ideological differences between the coalition partners, the 2024 GNU adopted a consensus-driven decision-making model. Therefore, major decisions required agreement among the top leaders of the coalition, effectively creating a collective leadership structure. This model was designed to prevent any one party from dominating the government and to encourage dialogue and negotiation as the primary mechanisms for resolving disputes. While this approach mirrored the collective decision-making of the 1994 GNU, it also carried the risk of decision-making paralysis, as achieving consensus among ideologically diverse parties proved challenging. The formation of the 2024 GNU was also accompanied by a commitment to comprehensive institutional reforms, particularly in the areas of anti-corruption, governance, and service delivery. The coalition agreed to establish independent oversight mechanisms and strengthen the powers of anti-corruption agencies to address the pervasive corruption that has eroded public trust in government.18ANC (2024) ‘Statement of Intent of the 2024 Government of National Unity’, op. cit. Clause 1.9 of the GNU plan is to strengthen ‘Foreign policy based on human rights, constitutionalism, the national interest, solidarity and peaceful resolution of conflicts, to achieve the African Agenda 2063, South-South, North-South and African cooperation, multilateralism and a just, peaceful and equitable world.’19Ibid.

The role of political compromise in maintaining stability and promoting peacebuilding

The compromises that led to the formation of the 2024 GNU were essential for maintaining political stability in a time of deep uncertainty. As a result, by bringing together the major political actors into a single coalition, the GNU avoided the risk of a prolonged political deadlock. The GNU also provided a platform for addressing the urgent socioeconomic challenges facing South Africa, including unemployment, inequality, and the crisis in service delivery. Political compromise was not only about power sharing but also about fostering a sense of national unity and reconciliation in a deeply divided society. The inclusion of parties with divergent ideologies in the GNU demonstrated a commitment to prioritising national interests over narrow partisan agendas. This spirit of compromise contributed to rebuilding public confidence in the political system, which had been eroded by years of corruption scandals, mismanagement, and political infighting. Moreover, the GNU played a key role in peacebuilding by promoting dialogue and cooperation among political actors who had previously viewed each other as adversaries. By institutionalising dialogue and compromise at the highest levels of government, the GNU helped to mitigate tensions and prevent the escalation of political conflict. This was particularly important in a context where the potential for unrest was high due to growing public frustration with poor governance and economic hardship. The compromise required all parties involved to embrace negotiations, concessions, as well as the willingness to collaborate across political lines. This was to strengthen and foster a political culture that values collaboration.20Medcalf, Graham (2024) ‘Lessons in Political Compromise and Stability’, LinkedIn, 9 July, Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/lessons-political-compromise-stability-graham-medcalf-afo9c [Date: accessed: 20 August 2024]. Somehow, this meant that political parties had to give up their own ideologies and individual political interests and thus define new universal ideologies that are principal to unity and collaboration in pursuit of a common seventh administrative vision towards the country’s progress.

Political compromise in the GNU’s seventh administration called for a renewed focus designed theoretically to ensure stability and continuity in the country. The 2024 GNU gave precedence to citizen-centred governance rather than power ambition or power consolidation efforts. This places a strong emphasis on transparency and accountability and creates an inclusive developmental imperative for realising the government’s potential and improving the quality of life of its citizens.21Sibanda, Omphemetse S. (2024) ‘South Africa’s political impasse threatens progress and unity as parties look to form GNU’, Daily Maverick, 10 June, Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2024-06-10-south-africas-political-impasse-threatens-progress-and-unity-as-parties-look-to-form-gnu [Date accessed: 18 August 2024]. Conceptually, a GNU or coalition government has the potential to foster a more comprehensive and equitable approach to policymaking fundamental for stability and peacebuilding in nations. This is due to the fact that different perspectives can enrich policy discussions and outcomes.22Umkhonto Wesizwe (2024) ‘Understanding a Government of National Unity’, MK Party, Available at: https://mkparty.org.za/understanding-a-government-of-national-unity [Date accessed: 20 August 2024]. Additionally, South Africa can learn from Germany, where coalition administrations are frequently used, including the ‘grand coalition’ between the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). These coalitions have ensured stable governance, despite the fact that they frequently necessitate substantial negotiation and compromise in policy matters.23Sibanda, Omphemetse S. (2024) ‘South Africa’s political impasse threatens progress and unity’, op. cit. Hence, negotiations and compromise processes must ensure that there is informed decision-making leading to policy efficiency and not policy paralysis that will hinder the attainment of peace and stability. It is also worth noting that this commitment is not a temporary or short-term resolution. This means that there must be the development of skills and a mentality that supports the effective negotiation and compromise essential for the GNU’s success. Therefore, the GNU’s implementation of political compromise is essential to South Africa’s endeavours to establish a stable democracy and a foundation for enduring peace and social cohesion and ultimately, maintaining stability.

Maintaining peace and stability

The GNU’s need to ensure peace and stability in South Africa is highlighted and described in the Statement of Intent and is enshrined in the Constitution. However, despite its success in averting a political crisis, the 2024 GNU faces significant challenges ahead in steering the nation and provinces in the right direction and creating a foundation for service delivery, peace, democracy and development.24Beukes, Jennica et al. (2024) ‘Unpacking the 2024 Government of National Unity in South Africa’, op. cit. On the one hand, there is the decision-making of political parties. For instance, in the realm of economic policy, a coalition that includes both left-leaning and right-leaning parties might struggle to implement comprehensive reforms. The resulting economic policies might be a blend of market-friendly and welfare-oriented measures, potentially lacking the coherence and effectiveness of a more singular vision.25Maleka, Mahlomola Stevens (2024) ‘The Implications of a Government of National Unity on Strategic Planning’, op. cit. Clause 18 of the GNU states that ‘The GNU shall take decisions in accordance with the established practice of consensus. Where no consensus is possible, the principle of sufficient consensus shall apply.’26ANC (2024) ‘Statement of Intent of the 2024 Government of National Unity’, op. cit. This is to note that geopolitical dynamics have significant implications for peacebuilding and stability, especially in a politically fragmented environment like South Africa. In the context of the ANC’s declining dominance, South Africa’s shifting position within regional and global alliances impacts its internal stability and peacebuilding efforts.

The country has a role as a leader in African diplomacy, peace missions, and organisations like the African Union (AU) and Southern African Development Community (SADC), G20 group of nations and the BRICS coalition. For example, South Africa has demonstrated its strong influence in peacebuilding and stability with its recent stance on the Israel-Gaza conflict.27Ndzendze, Bhaso and Hlabisa, Nhlakanipho (2024) ‘South Africa’s new coalition government’, op. cit. The geopolitical competition for influence within South Africa can either support peacebuilding by providing financial aid, investment, and mediation support or destabilise it by fuelling political divisions or encouraging resource extractive practices. Additionally, South Africa’s ability to mediate conflicts in the region depends on its domestic cohesion; internal instability risks reducing its diplomatic effectiveness and credibility. The issues of conflicts in the region, such as the 2021 riots and unrest, also must be faced to ensure peace and stability. Balancing international partnerships while addressing domestic socio-political challenges is crucial, as external pressures can either enhance or undermine peacebuilding efforts. Moreover, it is important that, in bringing together these diverse parties, an environment conducive to creating effective dialogue and reconciliation is fostered to promote peace and reduce conflict.28Umkhonto Wesizwe (2024) ‘Understanding a Government of National Unity’, op. cit. Therefore, the GNU Statement of Intent provides a trajectory towards peacebuilding and stability in the country.

Conclusion

The 2024 GNU represents a significant moment in South Africa’s democratic evolution. It underscores the enduring relevance of political compromise as a tool for managing political transitions and addressing crises in divided societies. Political compromise enabled previously opposing parties to work together in a unified government, thereby resolving ideological differences to prioritise the nation’s collective welfare. As such, the GNU’s legacy will likely be shaped by its ability to deliver on its commitments to reform, governance, and service delivery. If the coalition can successfully implement its policy agenda and address the socioeconomic challenges facing South Africa, it may provide a path for future coalition governments in the country. However, if it fails to address these issues or collapses under the weight of its internal contradictions, it could lead to further political instability and a loss of public trust in democratic institutions. Looking ahead, the experience of the 2024 GNU raises important questions about the future of South Africa’s political system. As the country becomes more politically fragmented, the likelihood of coalition governments becoming the norm increases. This shift necessitates a rethinking of how coalitions are negotiated, managed, and sustained in a context of deep social and economic divisions. The success or failure of the 2024 GNU will have far-reaching implications for how South Africa navigates these challenges and whether it can achieve the promise of inclusive, stable, and effective governance. It is hoped that the GNU will manage to operate and serve the interests of the people. The South African Government News Agency29South African Government News Agency (2024) ‘GNU: A new era for SA’, 5 July, Available at: https://www.sanews.gov.za/features-south-africa/gnu-new-era-sa [Date accessed: 19 August 2024]. contends that if the coalition holds, it is a win-win situation for all the parties who were able to compromise for the sake of the people, peace and the country’s stability.

Mahlatse Ragolane is a Research Fellow at the International Council on Human Rights, Peace and Politics (ICHRPP) Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies. His research interests include policy discussions, peacebuilding, governance and security. He holds a Master of Arts in Public Management and Governance from the University of Johannesburg’s School of Public Management, Governance and Public Policy.

Nthabiseng Gratitude Khoza is an Assistant Lecturer at the University of Johannesburg’s School of Public Management, Governance and Public Policy.