Introduction

Policy makers and scholarship on peacebuilding increasingly focus on reconciliation. In fact, peacebuilding efforts after violent experiences are usually accompanied by powerful calls to go the reconciliation route. Reconciliation is the mutual acceptance of the other in a peaceful relationship and the sustainability of that acceptance; accompanied by a commitment to bind relationships in accord with future interests rather than being stuck in a conflicted past. Yet reconciliation remains a profound challenge in societies that experience political violence. Zimbabwe is facing a similar situation despite a series of state-centred efforts at reconciliation. From the 1980 Policy of National Reconciliation to the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC), a constant pattern of inefficacy is observed.

This article arises from concerns about why reconciliation in Zimbabwe is elusive. The aim of the study, then, was to devise a restorative-based intervention to build capacity for reconciliation among a small sample of adults in Harare. The primary question was: How can people affected by political violence but continuing to live together build their own capacity to promote reconciliation in the absence of effective state interventions? I conceptualised a reconciliation that would be derived from the theory of restoration as an approach that can transform relationships toward peaceful interaction. This yielded a theoretical framework that combined elements of reconciliation, restorative justice and conflict transformation theories, which was the basis for designing and analysing findings. A qualitative methodology combining interviews and focus-group discussions was utilised. Action research was the main design, in which one action cycle was utilised by the action group to implement an intervention. Action group participants’ responses offer evidence of how building capacity for reconciliation needs to be conceptualised through interventions that are participatory, collaborative and centred on the locals. The article reveals that restorative-focused dialogical conversations are useful in restoring broken relationships among political opponents. This is a viable alternative for promoting reconciliation in the absence of effective state responses.

Background

In the aftermath of violent conflict there must be efforts made to explore new opportunities to nurture or build peace. Efforts to promote reconciliation have been undertaken in different societies with mixed results, often dependent upon the model implemented. Experiences from different countries show that local reconciliation interventions can claim a special place in peacebuilding. In a survey of 21 locally-based reconciliation interventions across the world, Dessel and Rogge1 concluded that there were multiple benefits in peacebuilding programmes in which the local assumes central agency. Some of the benefits observed include:

- Participants strengthen their perspective taking skills (perspective-taking is the process by which an individual views a situation from another’s point-of-view)

- Development of a sense of commonality with others

- Less inter-personal divisiveness

- Development of problem-solving skills

- Valuing new viewpoints

- Clarifying one’s beliefs

- Learning from others

- Honest discussions

- Willingness to cross social boundaries

- Raised awareness to respect others

- Increased understanding and empathy

- Improved communication

- Joint action on issues of common concern

- Understanding all of the above as compatible with democracy and political involvement

In the Middle East, the tensions and hostilities between the Jews and Arabs have been mediated through localised interventions to encourage reconciliation. Inter-ethnic encounter programmes have been established to address decisions, with emphasis on facilitating communication, trust and deeper understanding of the complex Arab-Jewish situation in Israel. The programmes, sponsored by European and United States-funded non-profit organisations, involved face-to-face contacts under the guidance of Jewish and Arab facilitators. In his assessment of the initiatives, Abu-Nimer makes several observations pointing out the benefits and limitations.2 He observes that the Arab-Jewish encounter programmes played an important role in thwarting some racist movements; the encounters also provided Arabs an opportunity to interact with Jews and express their views and perceptions of the conflict in a direct, honest and safe environment without fear of accusation, humiliation or violence; Jews also had the opportunity to understand Arab political perceptions and culture. Although limitations were observed, the general conclusion from Abu-Nimer’s work is that while total reconciliation was not achieved, the encounters encouraged co-existence; an important ingredient for the development of capacity towards reconciliation. Similarly, in an evaluation of local-based initiatives in Guatemala communities, Pinto concluded that such initiatives provided a foundation for promoting trust and the long-term national agenda for peace.3 This was made possible by the challenging of stereotypes, the growth of personal relationships and trust that facilitated consensus-building.

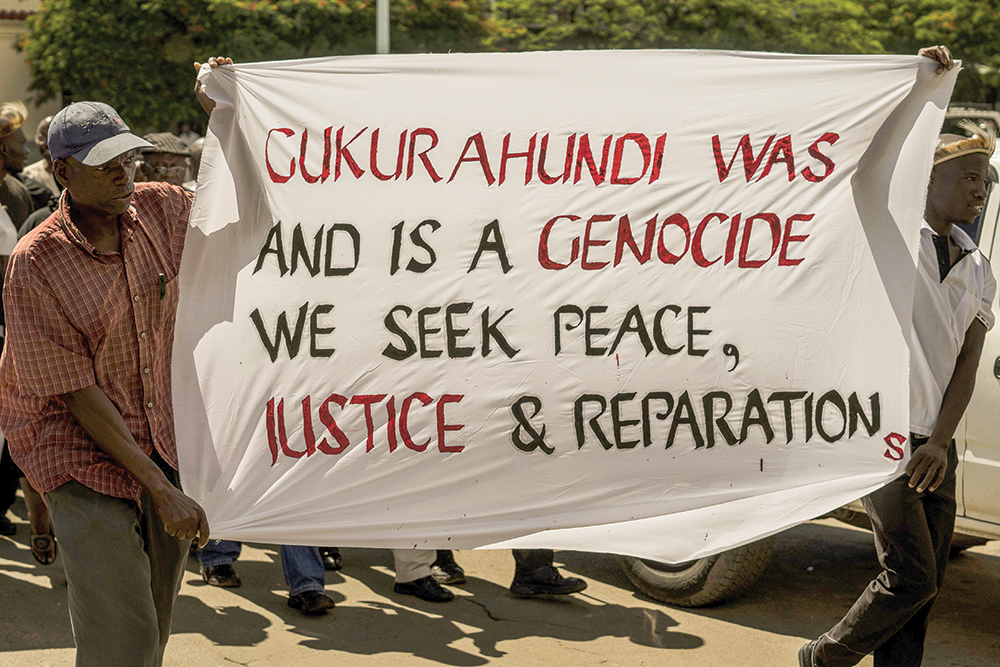

In Zimbabwe, there has been recurring violence since well before independence. Violence was established and institutionalised by colonial rule, culminating in the protracted war of independence against the settler government. Violence between the fighting groups had the most serious effects on ordinary citizens. More than 81 000 people died, were tortured or disappeared during the liberation struggle.4 The leading perpetrator was the repressive colonial system which forced people to take up arms. Following independence in 1980, various episodes of political violence still occurred. The dissident-cleansing operation Gukurahundi, carried out in the 1980s, in the Southern parts of the country ended with widespread deaths. Gukurahundi was an operation carried out by the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) to suppress the dissent from the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) aligned dissidents who were accused of plotting a coup against Robert Mugabe’s government. Gukurahundi resulted in many people losing their lives, the majority being civilians from the Midlands and Matebeleland provinces (where the Ndebele ethnic group was dominant). The fast track land reform programme which followed, necessary as it was, resulted in alleged Zimbabwe African National Party-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) aligned groups and supporters targeting sympathisers and supporters of the nascent opposition party, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). The campaign affected thousands of people through displacements and violence. In 2005, Operation Murambatsvina affected more than 700 000 people in a campaign by the government to get rid of illegal activities and structures in the cities.5 Most importantly, every national election since the 2000s has been marked by intra and inter-party political violence.6 Recently, the birth of internecine succession politics within political parties, ZANU-PF, MDC and the Zimbabwe People First Party (ZimPF) added a new dimension to political violence across the entire nation as rival factions clash.

The government reacted to the past events and violence that disturbed peace and divided people with a series of interventions meant to promote reconciliation. The question is whether such efforts have been effective? Evidence points to a lack of efficacy in state-centred reconciliation, that is, initiatives in which the government defines the problem and develops solutions without the involvement of the people who have been most affected by political violence.7 People remain deeply divided and polarised along race, politics and ethnic divides. The involvement of the state is not treated as unnecessary but the government-led initiatives have not adequately accommodated local concerns. The government, its agents and institutions appear to support hegemonic control of local citizens through interventions such as the Unity Accord (1987), that favours the interests of politicians at the national level at the expense of community interests. The heavy involvement of the state has undermined conditions that promote the central role of locals in reconciliation. This article emphasises ‘the local’,8 making a case for its assertiveness and central agency against a background of waning confidence in state-centred initiatives that have yielded poor results. To build capacity for reconciliation, recourse to localism through dialogue should be emphasised..

Building their work on Track II diplomacy concepts such as citizen peacebuilding, Hemmer et al9 make a strong case that peace initiatives should involve not just political leaders but also local people whose preferences must be reflected in outcomes. Using local dialogue as a medium for peacebuilding the authors note how people involved in local initiatives comprehend each other’s needs and interests in a manner that leads them toward collective decisions about their relations and new attitudes. Such agency can ultimately be exercised or expressed through what the authors refer to as ‘peacebuilding organisms’ – networked, specialised organisations engaging not only private citizens but media, local and national political leaders and other influential targets”.10 The notion of bottom-up peacebuilding gained traction through the work of Lederach11 who strongly argued that long-term grassroots peacebuilding is not only necessary for sustainable peace but may be the starting point when official leaders are stuck in intransigent conflict stances.

This article focuses on small-sample based evidence of community peacebuilding in Harare, undertaken by the author as part of peacebuilding research. Ward 30 is one of the two wards (together with Ward 29) that form the Glen View North constituency, located in the South Western part of the Harare metropolitan area and shares boundaries with wards 31 and 32 which fall under the Glenview South constituency. The population of Ward 30 is approximately 98 299 people, of which females are in the majority at 53 % while males account for 47% of the population. The Ward has been an MDC-Tsvangirai seat on the metropolitan Council since the party began to contest local government elections in 2000. However, ZANU-PF has always maintained a significant level of support in the area. Political violence has been a constant concern in the area. The frequency and intensity of the violence increases whenever there are political events in the Ward, indicating a worrisome culture of intolerance and distaste for open political competition.

Dialogical Conversations and Short-term Outcomes

An intervention plan was designed for a small sample of politically divided people in Ward 30 of the Glenview North constituency in Harare to enhance their capacity to develop skills for reconciliation. Afterwards, the outcomes of the intervention were evaluated. The first step was to identify the problem through interviews with randomly selected respondents from the Ward. This was done to understand the nature and intensity t of the politically motivated divisions making reconciliation difficult in Zimbabwe. The perspectives of the respondents would reveal the nature of the problem, its causes, extent and consequences. Fourteen interviews and four focus group discussions were held between February and April 2016 to appreciate the extent of the problem before an action group was constituted to design and implement the intervention.

Data gathering was followed by analysis and interpretation of the data sets, with a conclusion that led to the action part of the research. The interpretation and analysis of baseline data helped to acquire in-depth understanding about reconciliation challenges in Zimbabwe, and became the basis for formulating an appropriate intervention together with participants in the action group. Thirteen participants randomly recruited from the four focus group discussions constituted the action group together with the researcher. On the basis of the baseline data findings, the action group and the researcher met for a few days in May 2016 to plan an intervention that would achieve the aim of the study. Planning was done collaboratively to achieve agreed goals. The result was the adoption of dialogue as the intervention to foster peaceful relations among participants.

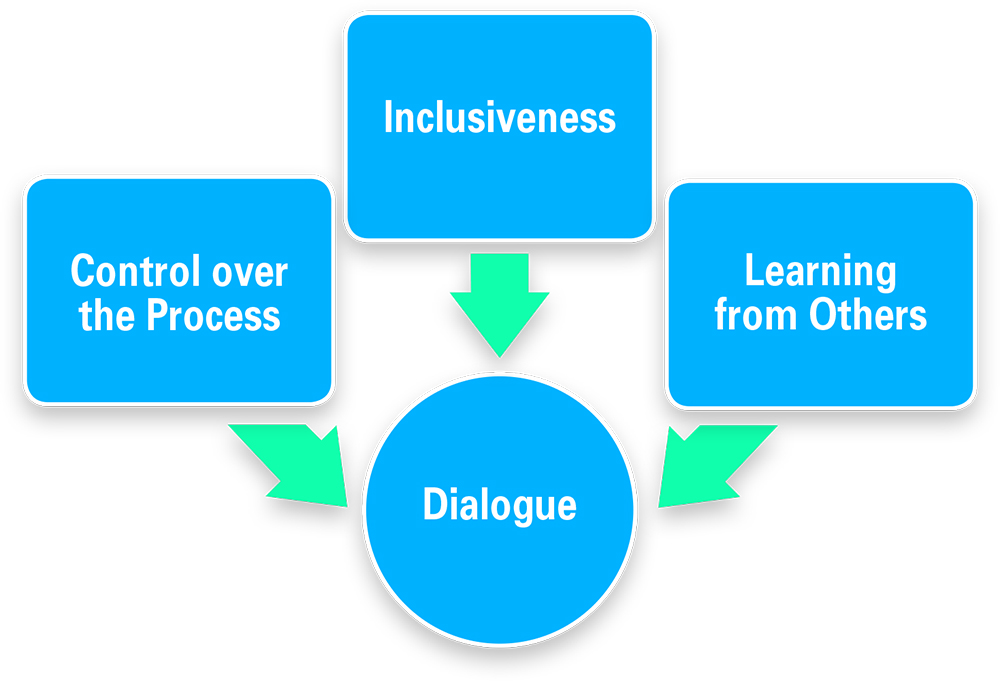

Participants selected dialogue to attempt to facilitate a shift in their mind-sets from stereotyping to accommodation through changing the nature and process of their conversations. Participants hoped that sharing through conversations would allow new understandings to emerge. Dialogue was also seen as a potential way for healing communities and relationships broken by political divisions, through inclusive engagement, control over what to discuss and the potential to learn from others. There was a conviction that dialogue would address the problem and potentially transform relationships. Figure 1 summarises participants’ reasons for choosing dialogue.

Figure 1: Participants’ Reasons for Choosing Dialogue

Four dialogue sessions were held from 28 May to 25 November 2016. The first session was an ice-breaker, meant for participants to know and understand each other. This laid the foundation and opened avenues for constructive communication among participants. In the second session, participants engaged in analysing the violent context and discussed why peace was necessary. The third session focused on determining the direction of change desired by the participants. This stage included discussions on the meaning of reconciliation and the necessary steps that needed to be taken by participants to encourage reconciliation. The last session was on determining the indicators of positive change towards reconciliation.

The dialogue sessions led to concrete action that resulted in the establishment of a garden project (peace garden) on 28 November 2016 in the location of the study. The garden was an action adopted to symbolise a desire to maintain the spirit of friendship, trust and co-existence beyond the verbal exchanges that characterised the dialogue sessions. Since the desire for positive change motivated the action research, the dialogue and the peace garden were subjected to evaluation. Evaluation aided in determining the effect of the intervention on the participants. Evaluation was implemented as a continuous process with mini-evaluations carried out at the end of each dialogue session. Observations were made during conversations on the whatsapp social media platform created by the group following the first dialogue session.

The political affiliations of the participants are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Participants’ Political Affiliation

| Political Party | Number of Participants | Percentage |

| ZANU-PF | 7 | 53.8 |

| MDC-T | 4 | 30.8 |

| ZimPF | 1 | 7.7 |

| National Constitutional Assembly (NCA) | 1 | 7.7 |

| Total | 13 | 100 |

Table 1 shows that the largest number of participants were affiliated to ZANU-PF (seven). The opposition party MDC-T included four participants, and the newly formed Zimbabwe People First (ZimPF) and National Constitutional Assembly (NCA) had one participant each. Studies on political violence in Zimbabwe suggest that most of the violent conflicts, other than the Gukurahundi episode, were a result of the political contests between the two major parties in the country: ZANU-PF and MDC-T. It was therefore important to have the two parties well represented in the action group and the dialogue process to induce positive behaviour.Post-intervention interviews demonstrated the power of dialogue in promoting reconciliation given the changes in attitudes and perceptions reported by participants. These findings are significant.

Activities of the Group were Beneficial to Participants

Of the 13 participants in the action group, nine (69.2%) reported to have had a very helpful experience while four (30.8%) found the experience to be either helpful or somewhat helpful. The ‘not helpful’ response was not reported. Explanations of the short answers generated a number of themes as follows.

Improved Understanding

Participants asserted that the group enabled them to discuss real issues that affected them across the political divide. They indicated that dialogue enabled them to explore issues that were affecting their relations and which could have otherwise been difficult to talk about. Participant 4 said:

Sharing and talking about forgiveness helped me realise that we are only divided by politics but our different ethnic backgrounds have almost common values that promote forgiveness and peace.

The process of re-storying and re-connecting enabled by dialogue facilitated a change among some participants. Prior to the intervention, participants held negative perceptions of “the other” that influenced negative relationships. The worst affected participants belonged to opposition parties who had lost hope as they experienced stereotyping from ruling party supporters. On the other hand, some participants from the ruling party were also disturbed by the widely held perspective that all ZANU-PF supporters are violent. The dialogue process therefore provided participants on both sides an opportunity to correct perceptions about each other. Samples of responses on individual participants’ feelings follow.

Participant 13:

It was my first time to be in a conversation with people from other political identities. At first I thought what we were doing was just to kill time but with time I began to realise that despite our differences what we discussed was really exposing the genuine interest of our community. After three or four meetings, I began to have a little sense of being liberated and connected. My emotions were slowing down.

Participant 12:

What we were doing was small but big in a way. In my case, I was completely surprised with people whom I had never talked to before coming close and initiating conversations. At first I thought this was not happening. The chats on whatsapp then showed me that people were coming closer through those conversations. There is this guy from the ruling party, I was beginning to feel close to him toward the last meetings but I used to avoid him. I’m not sure if this feeling will remain though but for now things appear to be moving in the right direction. We are doing the gardening together and I think we are okay…

It can be surmised that dialogue allows people to engage in conversations with former opponents by giving each space to talk and listen. The dialogue process allowed for change of perceptions and mind-sets towards each other. Participants who were not on talking terms or who considered others as their enemies began to connect, develop a sense of safety and less fear. Relationships were beginning to be established as participants began to define their common interests and build something new. New realities were beginning to emerge. The power of restoration and transformation embedded in dialogue was felt by the participants. There is cause for optimism that participants can develop the necessary capacity to work towards peace despite the varying and even polarised attitudes observed in the group at the start of the process.

Better Communication

Participants felt that the group experience was ‘very positive’ or ‘positive’ because dialogue laid the foundation for communication among them. Communication was ostensibly made easier by the social media platform, whatsapp. Participant 7 had this to say:

My fear was the communication we were having in the group will disappear with the end of the dialogue meetings. I have been proven wrong for now. We are continuing to know each other better because now we are talking every moment on whatsapp.

Dialogue has an impact on situations of poor or non-existent communication. Dialogue enables face-to-face encounters which encourage better understanding and communication. Through dialogue sessions decisions to further improve communication were made. Communication in turn reduces incorrect assumptions and misunderstandings as parties develop better understanding and appreciation of the other. Where there is good communication, misinformation which plays a significant role in inflaming conflicts, is corrected or eliminated. Even if participants were not yet a united block, they were at least developing an understanding and appreciation of the other through constant communication. They were no longer seeing each other as enemies but as potential friends who deserve to live with each other in peace.

Acting Together Enhances Tolerance

The dialogical conversations drew people closer. This dovetails with conflict transformation and restorative justice principles. Participants took deliberate action to transform relationships that were threatening peace by accommodating both victims and perpetrators in one forum. A tolerant attitude was developing among the participants and this would strengthen the capacity to promote reconciliation. Participant 2 said:

The meetings made it possible for me to see myself as part of the group. If we are not meeting, I feel like I’m missing something. It’s gradually becoming part of my life.

Dialogical conversation created space for the transformation of conflictual relationships. Participants involved themselves in a garden project that enabled them to remain together as a group after the four dialogue sessions. Participants also felt that participation in the dialogue sessions and working together in the garden was the source for the emerging tolerance. Participant 5 who had failed to sit next to participants who supported the opposition parties during the first meeting of the group amplified this point:

At first I thought something bad will happen in the discussions. I could not believe that I was in the same room with the guys from the opposition discussing all those sensitive issues without exchanging insults. My tolerance improved a bit as we began to frequent the garden. I am actually talking more to some of them and sometimes our discussions end up on hot political issues without getting personal about it.

The tolerance shown may seem miniscule given the deep animosity between supporters of the ruling party and the opposition in the general society, but it is a positive change in the small dialogue group. It does demonstrate the potential of dialogue and the attendant action to transform the behaviour of opposed individuals who elect to be part of peacebuilding initiatives. The fact that the participant found it difficult to sit next to supporters from rival parties was an indication of a serious intolerance. However following the dialogue sessions the participant was able to discuss politics with others and this was a sign of emerging tolerance which was developing. The co-existence that was demonstrated by participants was a positive sign that reconciliation can be realised in politically divisive situations. Tolerance enables people to appreciate each other and discover the possibility of common and shared perspectives and values. This further facilitates the growth of mutual respect which is an indicator of the nascent capacity to reconcile with others.

Conclusion

The findings of the study demonstrate a correlation between dialogical conversations and attitudes and perceptions that build capacity for reconciliation among participants of different political affiliations. Conversations facilitated a change of perceptions and attitudes among some participants. Prior to the intervention, participants held negative perceptions of “the other” that influenced negative relationships. Thus dialogue facilitated improved understanding and better communication among participants. Participants from different political groups who were not on talking terms or who considered others as their enemies began to connect, develop a sense of safety and fear less. The power of restoration and transformation embedded in dialogue was felt by the participants. The dialogical conversations encouraged tolerance. Participants took deliberate action to transform relationships that were threatening peace by accommodating each other throughout the dialogue sessions. They further established a permanent interaction platform through engaging in a garden project.

The participants who joined the peace initiative acknowledged that the situation in which politically powerful individuals define conflicts and attempt to find solutions to problems affecting them was unsatisfactory and needed to be improved. The 13 participants in the action group had experienced political violence and divisions, but their actions throughout the four dialogue sessions and the garden project demonstrated the yet to be fully exploited power of local interventions and dialogue to encourage reconciliation in Zimbabwe. This would be a significant alternative or additional resource to government-led initiatives.

Endnotes

- Dessel, Adrien and Rogge, Michael (2008) Education of Intergroup Dialogue: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 26 (2), pp. 199–238.

- Abu-Nimer, Mohammed (2004) Education for Co-existence and Arab-Jewish Encounters in Israel: Potential and Challenges. Journal of Social Issues, 60 (2), pp. 405-422; Abu-Nimer, Mohammed (1999) Dialogue, Conflict Resolution and Change: Arab-Jewish Encounters in Israel. Albany: SUNY Press, p. 95.

- Pinto, Diez (2004) Anticipating Consequences: What Bosnia Taught Us About Healing the Wounds of War.Human Rights Review, pp. 56–66.

- Hapanyengwi-Chemhuru, Oswell (2013). Reconciliation, Conciliation, Integration and National Healing: Possibilities and Challenges in Zimbabwe. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 13 (1), pp. 79–99.

- Masunungure, Eldred (2009) Defying the Winds of Change: Zimbabwe’s 2008 Elections. Harare: Weaver Press, pp. 18.

- Sachikonye, Lloyd (2011). When a State Turns on its Citizens: 60 Years of Institutionalised Violence in Zimbabwe. Aukland Park: Jacana, pp. 65–67.

- Machingauta, Mazvita and Friedman, Harris (2013). Developing Transpersonal Resiliency: An Approach to Healing and Reconciliation in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Interpersonal Studies, 32 (2), pp. 53–62.

- MacGinty, Roger. (2015). Where is the Local? Critical Localism and Peacebuilding. Third World Quarterly, 36 (5), pp. 840–856.

- Hemmer, Bruce et al. (2006). Putting the ‘Up’ in Bottom-up Peacebuilding: Broadening the Concept of Peace Negotiation. International Negotiation, 11, pp. 129–162.

- Ibid, pp. 133.

- Lederach, John. Paul (1997). Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, pp. 3.