Introduction

In most cases, political solutions to armed conflicts are professed by a plethora of local, regional and international actors. In practice, however, durable political solutions – typically symbolised through peace agreements – are scarce. While peace agreements may be signed, political willingness, as well as the ability to implement them, is often in short supply. Hence, many peace agreements remain words on paper, not actions in the field. This is also the case in Africa, where many conflict areas see peace agreements being signed, violated and forgotten.

This article examines the 2015 peace agreement in Mali and the case of the 2016 peace agreement in Colombia. The 2015 Bamako Agreement for Mali – despite hopes to end armed violence and provide a framework for peace – has had little impact on the ground and serves to illustrate some of the limitations of peace agreements. Does the commonly considered successful case of Colombia shed light on the struggling Malian peace process? This article suggests that the Colombian peace process does provide useful insights into the challenges in Mali. This is discussed in the context of what, with whom and when to negotiate. Following this analysis, some lessons learnt are identified, along with concluding remarks on how these two cases illustrate both the potential and limits of peace agreements.

Background

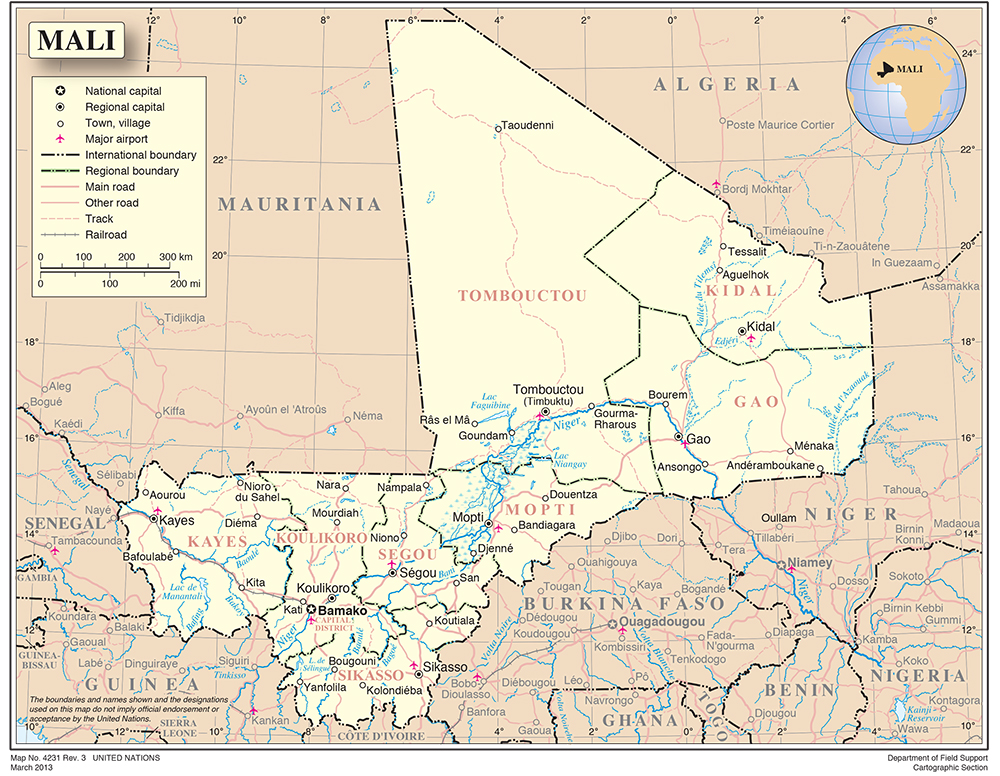

Both the Mali and Colombia conflicts started in the early 1960s. In Mali, various groups in the northern region have intermittently rebelled against the central authorities in the south. Typically, stated objectives include more autonomy, recognition and development funds for the north.1 The latest rebellion was started by the Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) in early 2012. With help from temporary alliances with Islamic jihadist groups, the MNLA effectively expelled the Malian Army from northern Mali and declared the Independent State of Azawad on 6 April 2012.2 A political crisis in Bamako, triggered by a coup in March 2012, caused regional and international wariness, particularly from its former colonial power, France. In January 2013, as Islamic jihadist groups advanced towards Bamako, France intervened – at the request of Mali’s interim president, Dioncounda Traoré. French forces in cooperation with Malian troops, regional states and Western forces, halted the advancements on Bamako. Since then, the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Mali (MINUSMA), and smaller European Union training missions, have helped stabilise the country.

In 2014–2015, a peace process – conducted with neighbouring Algeria as key mediator – took place between the Government of Mali and approximately eight armed groups.3 These groups were united under either the banners of the Platform (considered pro-government militias) or the Coordination of Azawad Movements, henceforth Coordination (rebel groups against the state). The Bamako Agreement was signed in May and June 2015 – first by the Platform and later by the Coordination – but implementation has remained very slow.4 In these last few years, however, the security situation has worsened, and a variety of groups and weak Malian Armed Forces struggle for control and legitimacy in the northern and central regions.

The Colombian conflict also started in the 1960s, when several communist-inspired rebel groups were formed. The largest, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), put forth a political programme to fight against inequality in the Colombian countryside. The FARC grew stronger in the 1990s, helped by increased revenue from its involvement in cocaine production, and exerted significant military power in the late 1990s. Out of fear of a communist takeover in Colombia, the United States (US) supported the Colombian government in its counter-narcotics and counter-insurgency operations. The war on the FARC, supported by the US and orchestrated by Colombian president Álvaro Uribe, significantly weakened the rebel group.

In 2010, newly elected president Juan Manuel Santos decided to pursue peace negotiations with the FARC. The peace process was secret during the two first years, and confidential during the next four years. In 2016, after a referendum in which Colombians narrowly rejected a first version of the peace agreement, the parties signed the agreement in November of that year. While armed conflict may be said to have ended, the peace process has faced significant obstacles with implementation and the security situation remains fragile, with several clashes between mostly criminal groups in previously FARC-controlled areas.5 As the 2018 presidential elections showed, Colombia remains polarised, lingering between peace and war.6

Some key differences in conflict trends and trajectories demand attention. First, while the rebel groups in Colombia sought regime change, the Mali conflict has traditionally been a separatist rebellion. Moreover, while Mali has seen four large-scale eruptions of violence and three peace agreements, fighting has remained constant in Colombia, where three previous peace processes ended without agreement.

Also, Colombia dealt with several armed groups, including paramilitary groups and the National Liberation Army (ELN), a smaller rebel group. Still, the number of groups in Mali is significantly greater. Importantly, the FARC has remained intact and stable throughout five decades of armed rebellion, even during the military weakening in the 2000s. In Mali, to the contrary, armed groups seldom last long without changing names, leaders or alliances.

Political Solutions and Peace Agreements

In this article, a political solution refers to the act of pursuing a negotiated way out of war and towards peace. It may start with intentions to reach a political solution; it may reach a key turning point with a peace agreement; and it may materialise through a variety of diplomatic, developmental and peacebuilding efforts over years and decades. Peace agreements, then, signed between at least two key actors, are more delimited in time. They may also provide the framework for peace that a political solution most often requires.

Engaging in a peace process and signing a peace agreement are, by definition, bilateral (or multilateral) acts. Continuing warfare to pursue military victory, on the other hand, is unilateral, as it does not require the other’s consent. As peace negotiations require political compromises, terrorist labels and the rejection of adversaries’ political nature typically block such initiatives.

To explain why armed actors reach political solutions, scholars note political willingness as the most important factor.7 A useful analytical vantage point is provided by readiness theory, in which Pruitt considers each actor’s readiness to negotiate. Readiness is comprised of motivation raised by a “dysfunctional” conflict that does not move it towards its goals, and optimism about actually reaching an agreement with an opponent that can commit their party to the settlement.8 In ripeness theory, Zartman presents a similar argument, in which parties find themselves in a “mutually hurting stalemate”, where the military route is no longer perceived as viable and where pursuing a political route (through negotiations) is.9 Some further requirements are typically some unity within groups, strategic political goals, and the ability to garner sufficient internal support to sign and uphold agreements.

Analysis: Elusive Peace in Mali

Several factors help explain why a political solution to the conflict in Mali remains elusive, and why the 2015 Bamako Agreement has had limited impact on the ground. In the following section, while drawing on the Colombian peace agreement when pertinent, the discussion touches on some of these factors in the framework of three questions: What to negotiate? With whom to negotiate? When to negotiate?

What to Negotiate?

Peace agreements that seek transformation of a conflict must somehow address the underlying issues. In Mali, the northern rebel groups’ key claims have been discussed in previous peace processes: the north’s special status, the decentralisation of power, the decreased presence and recomposition of the Mali Armed Forces, and more economic development funds.10 The Bamako Agreement from 2015 touches on these issues, but remains vague on how to solve them.11 Some stipulations have also been suggested to be counterproductive: while the creation of regional assemblies may be desired, the dynamics within the northern regions, including the many intergroup and intragroup tensions and conflicts, may instead become further intensified with the regional assemblies.12 Further, key issues such as terrorism and trafficking were barely touched on, and the agreement does not address two key parallel conflicts: the ideological challenge related to Islamist groupings; and intergroup and intragroup conflicts within the northern groups.13

In Colombia, the FARC’s key grievances, agrarian reform and political participation were negotiated. Drug trafficking, a key conflict driver, is also addressed in the peace agreement. While some key topics were discussed in Mali, the agreement is more goal-oriented than process-oriented, making the implementation phase an arena for debate, which has served to prolong the process. That the agreement was not concrete and did not address key issues, suggests that the underlying political willingness was low – not that the negotiation process itself was necessarily responsible. Also, in Colombia, similar solutions had been proposed earlier, but it was only at the particular time that there existed considerable political willingness to compromise. This conforms with Zartman’s suggestion that in the right moment, parties “grab on to proposals that usually have been in the air for a long time and that appear attractive only now”.14 Still, this does not render the process itself less important. Indeed, several elements from the Colombian peace process may help peace processes elsewhere: extensive learning from previous peace processes throughout the world, and hearing victims and civil society’s voices during negotiations.

With Whom to Negotiate?

Two elements in this context help to explain the limited impact of the 2015 Bamako Agreement. The first is the fragmentation and infighting of the groups present at the table. In the lead-up to the 2015 Bamako Agreement, the armed actors frequently changed leaders, names and alliances. Personal agendas and rivalries, along with repositioning ahead of the Algiers peace process itself, made negotiations particularly challenging, leading to vague stipulations at best. The northern populations’ feeling of inclusion was limited – and, hence, their support for the agreement followed similarly.15 Moreover, in the case of northern Mali, authorities “lack the means to impose their will on subordinate groups”, hence complicating any implementation of a political solution.16 Compared to the various groups in Mali, the FARC’s hierarchical nature facilitated negotiations. Leaders were able to negotiate and commit to political compromises, and post-agreement has been kept largely intact.17

A second element is the exclusion of key actors. While several groups behind the banners of the Platform and the Coordination were included, key jihadist groups were not. These groups include the Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Anser Dine al-Mourabitoun and the Macina Liberation Front.18 Including them would have provided recognition that few actors are willing to give, and would have complicated matters in numerous ways. However, excluding them entirely from any type of negotiation may not be desirable either. In Colombia, the smaller guerrilla group ELN was excluded, but did not sabotage the peace process – partly because it had some interest in talks succeeding and because it exerted little military impact on the ground compared with the excluded actors in Mali. In Mali, engaging in even indirect talks with jihadist groups remains controversial, and formal negotiations are – per now – unthinkable. Some suggest, however, that some form of communication or dialogue may be advantageous,19 and that better understanding of how jihadist groups operate and what role they play in local communities may enable different types of responses at the same time.20 As Rupesinghe argues, by removing the terrorist label from jihadist insurgents, one may recognise their “multifaceted identities – some as legitimate social/political actors and local protectors to communities”. This again “would open up more policy responses, including dialogue, and traditional, bottom-up conflict resolution”.21

In Colombia, as in Mali, armed groups have had various labels – including rebel, terrorist and criminal. Some groups may have multiple identities, and their labels may also change. In Colombia in the 2000s, President Álvaro Uribe was determined to defeat the FARC – a group he labelled narcoterrorists, suggesting it had no political agenda – militarily. In Colombia, the entry of Juan Manuel Santos into the presidency in 2010 mattered partly because, while rejecting its methods, he accepted the FARC’s political nature. This is not to say that actors such as the Mali government and France, its former colonial power, should necessarily include previously excluded groups in talks. However, there are reasons to reconsider a primarily militaristic approach,22 and to consider a greater role for dialogue and reconciliatory measures.

In Colombia, a nationwide peace agreement was negotiated with considerable success between armed actors. In Mali, however, where conflicts are highly localised, this type of peace negotiations may not be best. While Mali may need some overarching peace agreement signed with key rebel groups able and willing to uphold it, implicit or secret agreements or arrangements with other actors, such as jihadist groups, may also be needed. Moreover, as with President Juan Manuel Santos in Colombia, a peace process in Mali may be supported by a leader who simultaneously takes a strong stance against terrorist acts and delimits issues to be discussed, and who carefully opens up a space in which some form of dialogue may take place. To do so, secret phases – key in the first two years of negotiations in Colombia – may also prove fruitful in both dealing with various rebel and jihadist groups. In any case, what is needed in Mali is stronger engagement with the locals, and to deal with both larger issues – such as the origins of the Tuareg rebellions – as well as many micro-conflicts that fuel war in both central and northern Mali.

When to Negotiate?

When to negotiate is a potentially unanswerable question. Many scholars suggest there are certain ways to analyse the military power relations between armed actors to determine when they would be incentivised to negotiate. However, reliable information is often in scarce supply, both about conflict dynamics and actors’ military capabilities and intentions. Zartman suggests the parties ought to look for “ripe moments”, when they are in a costly predicament and find that negotiations may be the best means to pursue goals. However, the importance of subjective perceptions complicates this. Indeed, leaders’ subjective perceptions of conflict dynamics and the interpretation of adversaries make it difficult to prescribe when the right time to negotiate is. On the ground in Mali, the incentives to implement the agreement seem few, and “parties are more interested in the process than in peace itself”.23 When a peace process is seen as a tactical measure, not a strategic one, it does not bode well for reaching durable solutions.

However, a “ripe moment” also requires parties to perceive the political route as a viable means to reach some of its goals. In Mali, the political route has historically been pursued, but parties have seldom had much confidence in it. This relates both to high mistrust between parties and towards peace agreements. Indeed, the Bamako Agreement signatories in 2015 were marginally willing to commit to political compromises. This is evident in the few concrete agreements reached, where most substantial issues were left to be decided during implementation. The key role of external actors to push through the Bamako Agreement suggests that the parties themselves did not have sufficient willingness to do so. The opposite was the case in Colombia – the key armed actors themselves initiated the process and brought it forward, with only facilitation help from external actors.24

Rather than when to negotiate, more important questions may be what measures to use at what time. When the most appropriate time is, however, is difficult to specify. In Colombia, armed actors initiated talks themselves, and pragmatically included third parties to make the negotiation process sustainable. Through a combination of secret phases and confidential ones, they managed to establish sufficient belief in the other parties’ intentions before making it public.

However, adapting such lessons learnt to Mali is not straightforward: the contexts, conflict dynamics and actors are very different. For example, including fewer parties at the negotiation table in Mali may neither be feasible nor constructive. Also, the long and formal peace process in Colombia may not be feasible nor desired in Mali; other processes at the national and local level are necessary. The Anefis process is one example, where leaders of the Coordination and the Platform themselves, and with minimal international presence, engaged in talks to reduce violence after the Bamako Agreement.25 In general, continuous adaptation to a changing conflict context is crucial, including for the external actors and mediators.26 Indeed, Mali’s search for peace requires its own measures at the right time. Moreover, the nature of each group must be taken into account – treating jihadist and various rebel groups similarly is politically infeasible and probably not constructive. Going forward, then, the expanded and pragmatic use of various types of dialogue and local consultation processes may constructively accompany military measures to end Mali’s conflicts.

Conclusion

This article sought to explain the limited impact of the 2015 Bamako Agreement in Mali through an analysis of what, with whom and when to negotiate peace. It has, moreover, compared it with the 2016 peace agreement in Colombia and thus illustrated the potential and limits of peace agreements.

The 2016 agreement in Colombia has shown some of the potential of peace agreements. It was a strenuous process that attempted to deal comprehensively with root causes and provide a framework for peace. While implementation is slow, and security concerns remain high, it has been a milestone that may possibly provide the starting point for a decades-long process of peacebuilding, development and reconciliation.

The 2015 Bamako Agreement, on the other hand, has shown some of the limitations of peace agreements. Compared to the 2016 Colombian peace agreement, it has not served to substantially transform the conflict. Rather, the conflict landscape remains fluid, where even signatories’ support and efforts to implement it remains limited. While the agreement provides a reference point in the work to end conflicts in Mali, actors continue to clash and operate without much regard for it. Distrust towards each other, and low confidence in the prospects of a peace agreement serving their interests and actually being implemented, provides little hope. Under such circumstances, the impact of peace agreements remains limited.

Endnotes

- Pezard, Stephanie and Shurkin, Michael (2015) Achieving Peace in Northern Mali. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation, pp. 7, 12.

- Wing, Susanna D. (2016) French Intervention in Mali: Strategic Alliances, Long-term Regional Presence? Small Wars and Insurgencies, 27 (1), p. 61.

- Alliances of armed groups in Mali are fluid. For more on actors and alliances, see Maïga, Ibrahim (2016) Armed Groups in Mali: Beyond the Labels. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies.

- For more on the peace process, see Boutellis, Arthur and Zahar, Marie-Joëlle (2017) A Process in Search of Peace: Lessons from the Inter-Malian Agreement. New York: International Peace Institute.

- International Crisis Group (ICG) (2017) Colombia’s Armed Groups Battle for the Spoils of Peace. Bogotá: ICG.

- Drange, Bård and Opdahl, Maja Lie (2018) Colombia between Peace and War: The 2018 Presidential Elections and the Way Forward. Oslo: NUPI.

- Zartman, William (2001) The Timing of Peace Initiatives: Hurting Stalemates and Ripe Moments. The Global Review of Ethnopolitics, 1, pp. 8–18; and Pruitt, Dean (2005) Whither Ripeness Theory? Virginia: George Mason University.

- Pruitt, Dean (2005), op. cit., p. 7.

- Zartman, William (2001), op. cit.

- Pezard, Stephanie and Shurkin, Michael (2015) op. cit., p. 7.

- Wiklund, Cecilia Hull and Nilsson, Claes (2016) Peace in Mali? An Analysis of the 2015 Algiers Agreement and its Implementation. Stockholm: Swedish Defence Research Agency, p. 34.

- Reeve, Richard (2014) Devils in the Detail: Implementing Mali’s New Peace Accord. London: Oxford Research Group, p. 4.

- Wiklund, Cecilia Hull and Nilsson, Claes (2016) op. cit., p. 10.

- Zartman, William (2001) op. cit., p. 8. See Drange, Bård (2018) Kvifor forhandle fred? Ein analyse av forhandlingsstart i den væpna konflikten i Colombia. Internasjonal Politikk, 76 (3), or consult the English-language MA thesis on which this was based: Drange, Bård (2017) Peace in Protracted Conflicts: Explaining Peace Negotiation Onset in the Colombian Armed Conflict. MA thesis. Oslo: University of Oslo.

- Wiklund, Cecilia Hull and Nilsson, Claes (2016) op. cit., p. 15.

- Pezard, Stephanie and Shurkin, Michael (2015) op. cit., p. 25.

- The International Crisis Group (2017, op. cit.) reckoned about 1 000 dissidents in 2017, but more may come as implementation and the disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration processes slow down.

- These main jihadist groups merged and formed the Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin’ (Group to Support Islam and Muslims) in 2017; see Boutellis, Arthur and Zahar, Marie-Joëlle (2017), op. cit., p. 32.

- Campana, Aurélie (2018) Between Destabilization and Local Embeddedness: Jihadist Groups in the Malian Conflict since 2015. Montréal: Centre FrancoPaix, p. 26. See also Thurston, Alex (2017) Speaking with Jihadists: Mali Weighs its Options. New York:

The Global Observatory. - Rupesinghe, Natasja (2018) The Joint Force of the G5 Sahel. An Appropriate Response to Combat Terrorism? Conflict Trends, 2018/2.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.; and Bøås, Morten (2018) Rival Priorities in the Sahel: Finding the Balance between Security and Development. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainsitutet.

- Boutellis, Arthur and Zahar, Marie-Joëlle (2017) op cit., p. 2; see also Campana, Aurélie (2018) op. cit., p. 10.

- This was a key factor for success in Colombia. See Drange, Bård (2017) op. cit. and Drange, Bård (2018) op. cit.

- ICG (2015) Mali: la paix venue d’en bas? Dakar: ICG; and Wiklund, Cecilia Hull and Nilsson, Claes (2016) op. cit., p. 16.

- De Coning, Cedric and Gray, Stephen (2018) Adaptive Mediation. Conflict Trends, 2018/2.