Introduction

Just as Somalia has begun “to lift itself from the ashes and debris of war”,1 perceptions of Somali identity in Kenya have reached a new low. Even from before Kenya’s independence, suspicion of the background, political opinions and citizenship of Kenyan-Somalis plagued Kenya’s development, and this suspicion has now merged with a narrative of foreign terrorism that pits Kenyan-Somalis against their own nation-state. How has this come about, and what does it mean for Kenya’s fight against terrorism? In this article, I argue that the inability of the Kenyan state to distinguish between Somali Islamists and Kenyan-Somalis represents a missed opportunity at national integration. Specifically, the move towards a federal Somalia of autonomous regions should assuage old Kenyan fears of Somali irredentism and desires for secession. Kenyan-Somalis are too readily being associated with coastal Muslim appeals for secession, even though citizens close to the Kenya-Somalia border no longer show interest in political victories at the expense of socio-economic well-being. The time is ripe for a Kenyan state that includes Kenyan-Somalis in its vision of the nation, and yet this is the very moment in which the state is doing most to frame Kenyan-Somalis as foreign aliens.

In April 2014, following numerous terrorist grenade attacks and an explosion in Eastleigh that killed six,2 Kenyan authorities swept areas of Nairobi dominated by those of Somali ethnicity in an effort to identify those without appropriate citizenship or immigration documents. Approximately 900 people suspected of residing in Kenya illegally were brought to Kasarani stadium, where they waited for days to be screened for identity documentation and were then either returned home or were deported to Somalia or the Dadaab refugee camp.3 This strategy by Kenyan authorities forms part of Operation Usalama Watch, “an effort to disrupt Al-Shabaab support within Kenya.”4 It has been criticised by Human Rights Watch in no uncertain terms:

The round-up operation, which began on April 1, 2014, has been riddled with abuses […]. Government security forces have raided homes, buildings, and shops; looted cell phones, money, and other goods; harassed and extorted residents; and detained thousands – including journalists, Kenyan citizens, and international aid workers – without charge and in appalling conditions for periods well beyond the 24-hour limit set by Kenyan law.5

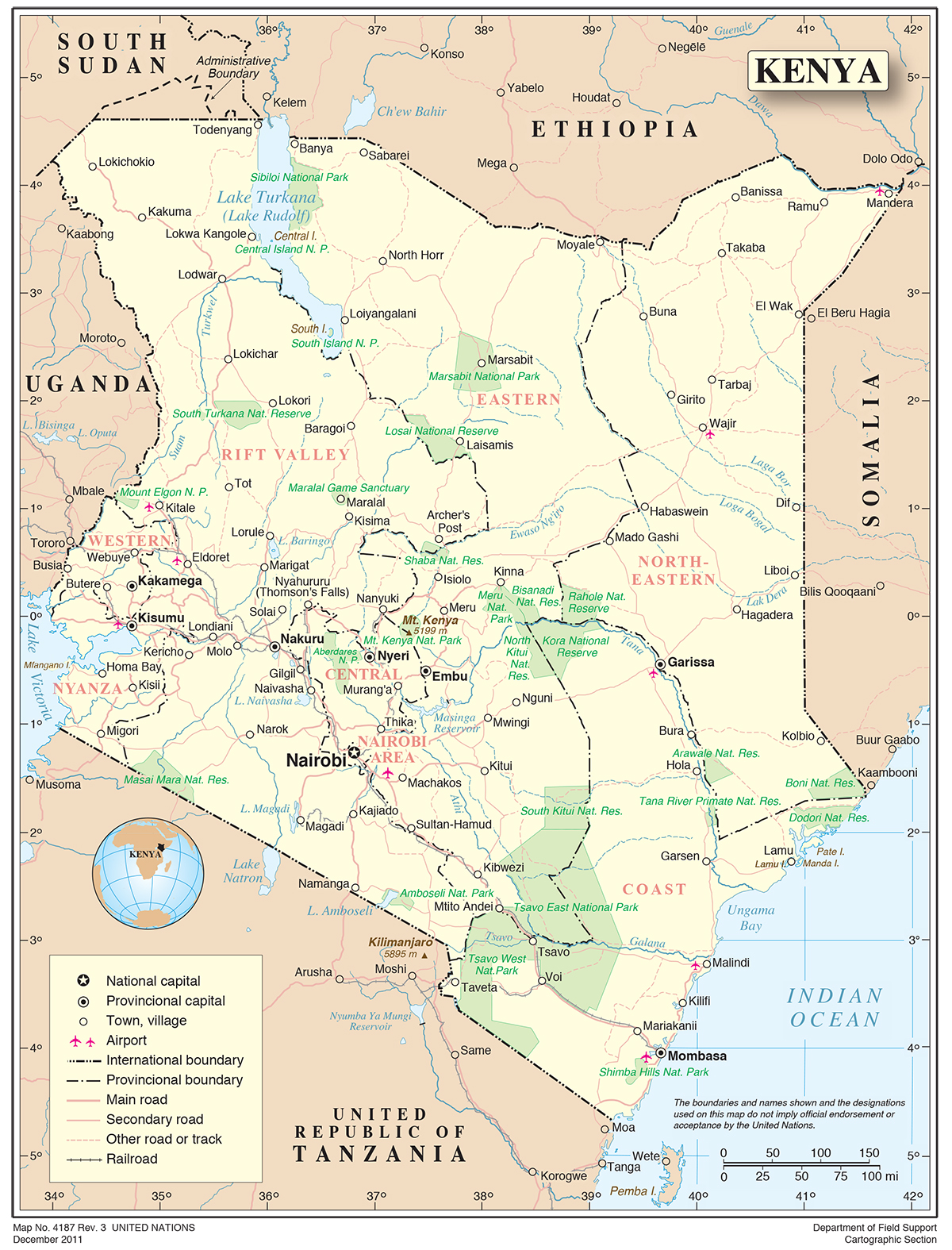

Operation Usalama Watch fits with President Uhuru Kenyatta’s self-depiction as “a hard leader able to make hard, sovereignest choices in the face of international adversity”.6 Although Kenyatta entered office only after Kenya’s October 2011 intervention into Somalia, his administration has borne the brunt of Al-Shabaab’s retaliatory terrorist attacks – the worst cases of terrorism in Kenya since the 1998 bombing of the United States embassy. Seven months after Kenyatta assumed office, Al-Shabaab lay siege to the Westgate shopping centre in Nairobi, leaving 67 people dead. This was followed by the killing of approximately 68 people in Mpeketoni, Majembeni and Poromoko in June 2014; the killing of 28 people in a bus in Mandera in November 2014; the killing of 36 people in a Mandera quarry in December 2014; and the killing of 147 people on the campus of Garissa University College in April 2015.

It is important to note these grievous attacks to put into context the Kenyan security services’ harsh response. Broadly speaking, terrorist acts are being sponsored by Al-Shabaab operators in Kenya, who have also engaged in Kenya-based recruitment, especially on the Kenyan coast under the auspices of Al-Hijra.7 Authorities are therefore drawing on the coercive capacities of the state to attempt to deal with an escalating problem that questions their ability to provide basic law and order. To give some indication of the fear at play among Kenyan citizens, a December 2014 poll found that 67% of citizens felt “crime/insecurity/terrorism” to be among the top three problems facing Kenya.8 Domestic insecurity is a complex challenge, and one that will not be solved by simply pointing fingers at the Kenyan state for not developing the country fast enough. Rather, it is important to distinguish between different security strategies and identify which are based on old problems and are currently failing to live up to the demands of current challenges. As David Anderson and Jacob McKnight write: “[T]his is the nebulous, but potentially pervasive enemy that Kenya must confront: an enemy that is no longer confined to Somalia, or even to the Somali, but one that appeals directly to the Ummah [community] throughout East Africa, and especially in Kenya.”9

Approaches to the Kenyan-Somali Question through History

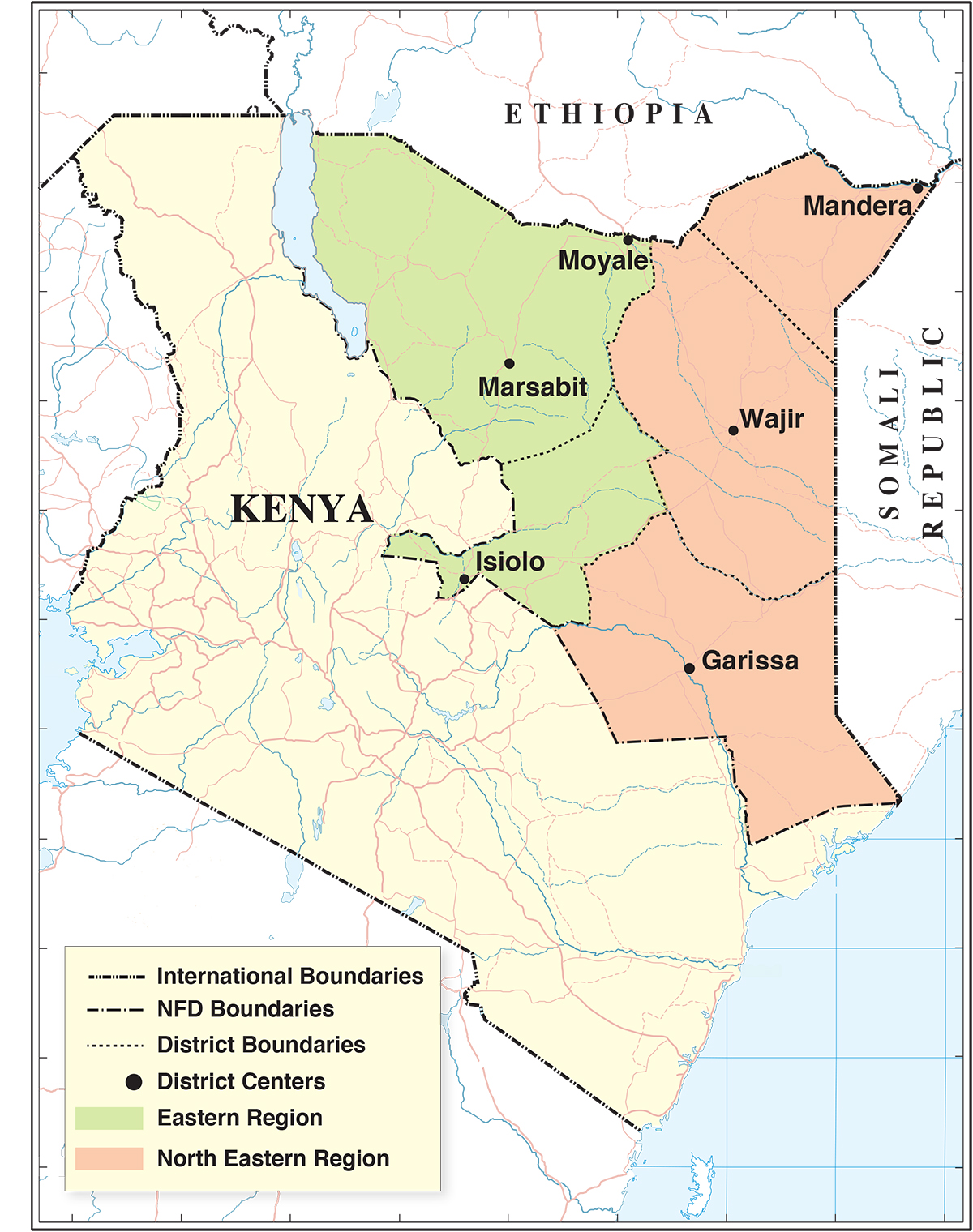

Human rights groups are, rightly, concerned with the level of resentment and suspicion towards Somalis in Kenya. Resentment for Somalis is, however, by no means a new phenomenon, and has existed in different forms since before Kenya’s independence in 1963. Somalia became independent before Kenya in 1960, unifying the two territories of British and Italian Somaliland. The five points of the Somali flag’s star signify the five territories that Somali politicians used to consider as hosting the Somali people and that, together, form Greater Somalia. Three territories lay outside the newly independent Somalia: the Ethiopian Ogaden, Djibouti and north-eastern Kenya.

As an example of the permanence of those of Somali ethnicity living in Kenya, Table 1 tracks the Somali population of Wajir, in north-eastern Kenya, from 1911 to 2009.

Table 1: Population of those of Somali Ethnicity in Wajir, 1911–200910

| Year | Number |

| 1911 | 23 000 |

| 1926 | (approx.) 46 000 |

| 1936 | 24 647 |

| 1939 | 9 633 |

| 1949 | 40 000 |

| 1989 | 119 672 |

| 2009 | 661 941 |

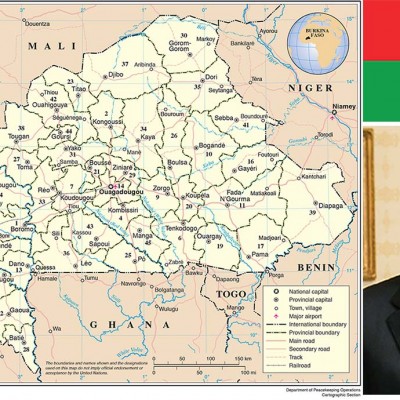

Northern Frontier District of Kenya12

Because Somalia achieved independence before Kenya, Somali politicians appealed to the British colonial authorities either to assign Kenya’s Northern Frontier District to Somalia before Kenyan independence, or else to allow a referendum to see if the population desired to secede from Kenya. Instead, the British government sent two commissions of inquiry that it hoped would help decide: the Northern Frontier District Commission and the Regional Boundaries Commission. Vincent Bakpetu Thompson explains that “the British underestimated the intensity of Somali feeling” and were surprised at the strength of representations made by Kenyan-Somalis to demand secession.11 This put the British in a difficult position. First, they were afraid of the implications of acquiescing to principles of self-determination, given the ubiquity of such claims throughout the empire. Second, because of the negotiations underway with burgeoning Kenyan politicians on how to make the independent country of Kenya work, British authorities were aware that placing power in the hands of locally dominant ethnic groups would not guarantee that minorities would be respected and included, even in their areas of origin. Blinded by these two fears, the British government avoided the question and instead hoped that implementation of a more federal constitutional structure, as proposed by the Kenya African Democratic Union, would give the right amount of regional autonomy to satisfy both sides of the debate.

The British authorities could not have been more wrong. From 1964 to 1967, Kenyan-Somalis and Somali insurgents employed violence to try and force the question of secession – a period of civil conflict known as the Shifta War. Under Jomo Kenyatta, the Kenyan state renounced the regionalist leanings of its independence constitution and instead reworked colonialism’s preference for divide-and-rule, whereby competing groups were played off against each other with a centralised state retaining all capacities for legitimate violence. Kenyatta feared competing demands for self-determination, both in the north-east and along the coast, perhaps because the Mau Mau uprising of Kikuyu against the colonial state – which gave Kenyatta legitimacy in the eyes of many Kenyans – was itself built on similar claims to self-determination. Kenyatta’s response to Somalis in the north-east was unremitting, and was followed even more aggressively under the second president, Daniel arap Moi. Although details are hard to retrieve, in November 1980, state authorities are alleged to have massacred approximately 3 000 ethnic Somalis of Bulla Kartasi in retaliation to a previous ambush of government officials by local bandit Abdi Madobe. Further, in February 1984, around 5 000 of the Degodia Somali sub-clan were killed at Wagalla airstrip.13

Apart from these acts of violence against the Somali population, the Kenyan government screened residents of the north-east to differentiate between those considered genuinely Kenyan, and those who should be ‘returned’ to Somalia. Emma Lochery consolidates an analysis of a 1989 screening and describes that “[t]hose who were deemed to belong to a lineage ‘indigenous’ to Kenya were issued pink screening cards; those declared non-citizens were deported”.14 At a base level, this forms part of a false ‘settler’ versus ‘native’ distinction that ignores sub-Saharan Africa’s grand history of migration,15 and specifically discriminates against nomadic and pastoral people as less-genuine citizens than those who are agrarian or urban. The bias plays out in less-than-objective attempts to identify who is not Kenyan:

…from the first day of screening, people queued for hours before presenting themselves to the panels of elders. They had to bring identification documents and answer questions posed by the panel. Individuals had to recite their genealogy and identify their main tribe, sub-tribe, clan, sub-clan, and jilib, the smallest unit of clan organization responsible for mag, blood compensation. Other demands were arbitrary. Individuals had to know the name of their chief and assistant chief and were sometimes judged on their ability to speak KiSwahili or answer questions about Kenyan history and politics. Some people were asked for detailed geographical descriptions of their birthplaces…16

Indeed, pastoral people are so little understood by the Kenyan state that the census has consistently been biased against them by asking: ‘How many people reside in this household?’ as a way of calculating population – even though such communities tend not to reside in fixed households for long durations.17 The statistical irregularities that resulted led Planning Minister Wycliffe Oparnya to announce the cancellation of results from eight districts in the north-east.18 These contestations over population figures have direct bearing on the financial support received by the region, because the amount of national revenue allocated to devolved governments is calculated by an algorithm (organised by the Commission on Revenue Allocation) that uses population figures as one of its key variables.

Navigating Kenyan-Somali Identity in a Post-9/11 World

When the Northern Frontier District Commission carried out its visits to the north-east of Kenya in 1962, it found that – for the question of whether the north-east should secede from Kenya and join Somalia – “division of opinion almost coincided with the division between Muslim and non-Muslim.”19 At that time, this religious element was anecdotal and of no political relevance either to Kenya or Somalia. Instead, pan-African, pan-Arab and pan-Somali beliefs held prime importance for shaping political ideals. The post-9/11 world, however, has seen the emergence of a worldwide narrative of Islamic radicalism, for which the territorial gains of Al-Shabaab in Somalia represented one of the most focused outlets – in many ways a precursor to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

In Kenya, this means a dangerous blending of long-lasting Kenyan-Somali grievances with radical calls for Islamic jihad. At the local level, however, Kenya’s Muslims – who make up over 11% of the total population, according to the 2009 census – hold extremely diverse political demands. For pastoralists of the north and north-east, concerns include land access for cattle grazing, the availability of water points and access to markets. Insecurities are most evident in cattle rustling (in the north) and a poorly regulated border with Somalia (in the north-east). For coastal Muslims, on the other hand, political distress lies primarily in the manipulation of title deeds for political ends, the state’s lack of recognition of customary courts and youth unemployment. Insecurity at the coast was sparked by movements for secession by the Mombasa Republican Council, which has no appeal to those outside coastal areas. In response to the threat of home-grown terrorism on the coast, Kenyan security forces are suspected to have eliminated radical preachers and planted evidence when they felt their killing of suspects would not be justified in the courts.20

Conclusion

The concerns of the Muslim population of Kenya differ by location, and yet in dealing with the terrorist threat, the Kenyan government is relying on the same centrist methods developed during the Shifta War – methods that ultimately are based on a fear of the unknown. Instead of getting to know local situations and responding to local needs, time and again the government applies the logic of patronage and political manipulation. Community leaders who understand local situations find themselves at the periphery of political decision-making, and instead the state turns to its friends in the region, hoping that divide-and-rule policies will compromise opposition. In a 1963 analysis of the political tensions in Kenya’s north-east, I.M. Lewis complained that there was “still not a single Somali District Officer or police officer beyond the rank of Chief Inspector”.21

Although there have, since then, been higher-level appointments of Somalis, these have not been in a spirit of trying to learn more about the region’s complexities. Kenyan-Somalis were, for example, promoted under Moi when the 1982 attempted coup led the president to form alliances with smaller ethnic communities traditionally on the periphery of politics. Hussein Maalim Mohamed became Minister of State in 1983 and his brother, Mahmoud Mohammed, became Chief of General Staff in 1985.22 However, co-optation into Nairobi-based politics is very different from getting in touch with local concerns – something clear in the appointment of Mohammed Hussein Ali, also a Kenyan-Somali, to the position of Commissioner of the Kenya Police in 2004 by President Mwai Kibaki. In 2010, Ali was indicted by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity after allegations were made that his office ordered the ‘shoot to kill’ policy following the disputed 2007 elections.23 Regardless of the merits or shortcomings of these national figures, their appointments have not rewritten the script of the state’s basic approach to Kenyan-Somalis. At no point in Kenya’s history has the government been prepared to devolve security functions in the north-east in a way that can give Kenyan-Somalis reason to believe their nation accepts them as equals. Until this fundamental need is addressed, the methods employed by the Kenyan government towards the Kenyan-Somali population will continue to frame them as enemies of the state.

Endnotes

- Morrow, R. (2014) Preventing Violent Conflict in Somalia: Traditional and Constitutional Opportunities. Conflict Trends, 1 (2014), pp. 11–19, p. 11.

- BBC News (2014) ‘Kenyan Nairobi Explosions Kill Six in Eastleigh’, 1 April, Available at: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-26827636> [Accessed 2 July 2015].

- Al-Jazeera (2014) ‘Kenyans Question Mass Arrests of Eastleigh Somalis’, 7 April, Available at: <http://stream.aljazeera.com/story/201404072028-0023625> [Accessed 2 July 2015].

- Anderson, D.M. and McKnight, J. (2014) Kenya at War: Al-Shabaab and its Enemies in Eastern Africa. African Affairs, 114 (454), pp. 1–27, p. 3.

- Human Rights Watch (2014) ‘Kenya: End Abusive Round-ups’, 12 May, Available at: <http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/05/12/kenya-end-abusive-round-ups> [Accessed 2 July 2015].

- Burbidge, D. (2015) The Shadow of Kenyan Democracy: Widespread Expectations of Widespread Corruption. Surrey: Ashgate, p. 51.

- Meservey, J. (2015) False Security in Kenya: When Counterterrorism is Counterproductive. Foreign Affairs, 21 January. See also Anzalone, C. (2012) Kenya’s Muslim Youth Center and Al-Shabab’s East African Recruitment. Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point: CTC Sentinel, 5 (10), pp. 9–13.

- Ipsos Public Affairs, (2014) ‘SPEC Barometer’, 19 Dec , p. 24.

- Anderson, D.M. and McKnight, J. (2014) op. cit., p. 26 (emphasis in original).

- The 1911–1949 figures were obtained from Thompson, V.B. (2015) Conflict in the Horn of Africa: The Kenya-Somalia Border Problem 1941–2014. Lanhan, MD: University Press of America, p. 21. The 1989 figure was obtained from Central Bureau of Statistics (1994) Kenya Population Census: Volume 1, 1989, table 6, p. 26, summing ‘Ajuran’, ‘Degodia’, ‘Gurreh’, ‘Hawiyah’, ‘Ogaden’ and ‘Somali-so-stated’. The 2009 figure was calculated by applying ethnic composition percentages of Wajir County to the 2009 population figures of Wajir. Ethnic composition figures obtained from Burbidge, D. (2015) ‘Democracy versus Diversity: Ethnic Representation in a Devolved Kenya’, Working Paper, Princeton University, p. 14.

- Thompson, V.B. (2015), op. cit., p. 94.

- Whittaker, H. (2015) Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Kenya: A Social History of the Shifta Conflict, c. 1963–1968. Leiden: Brill, p. 4.

- Kenya National Assembly Official Record (2010) Speech by Aden Duale, 25 March, p. 38; Hassan, A.I. (2008) ‘The Legal Impediments to Development in Northern Kenya’, Consultative Meeting for Members of Parliament, 22–23 August, Naivasha; Lochery, E. (2012) Rendering Difference Visible: The Kenyan State and Its Somali Citizens. African Affairs, 111 (445), pp. 615–639, p. 621; Mohammed, H. (2009) Wagalla Massacre: Human Rights Abuses against Minorities in East Africa and its Consequences. MSc thesis, University of Oxford.

- Lochery, E. (2012), op. cit., p. 616.

- Mamdani, M. (2001) Beyond Settler and Native as Political Identities: Overcoming the Political Legacy of Colonialism. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 43 (4), pp. 651–664.

- Lochery, E. (2012), op. cit., p. 629 (emphasis in original).

- Jerven, M. (2013) Poor Numbers: How We are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do about it. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, p. 74.

- Ibid, p. 73.

- Thompson, V.B. (2015), op. cit., p. 88.

- Al-Jazeera (2014) ‘Inside Kenya’s Death Squads’, December, Available at: <http://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/KenyaDeathSquads/> [Accessed 3 July 2015].

- Lewis, I.M. (1963) The Problem of the Northern Frontier District of Kenya. Race & Class, 5 (1), pp. 48–60, p. 56.

- Lochery, E. (2012), op. cit., p. 624. See also Hornsby, C. (2012) Kenya: A History Since Independence. London: I.B. Tauris, p. 411. Hornsby puts the year of promotion of Mahmoud Mohammed at 1986.

- Charges against Ali were dropped by the International Criminal Court on 23 January 2012.