Introduction

Social media platforms play a prominent role in modern society by providing tools for various voices to communicate ideas, perspectives and worldviews. Such potential has been illustrated by the role of these platforms in supporting social movements, mobilisation in defence of the environment, and the defence of marginalised communities and groups across different latitudes.[1]However, in many instances, social media has also been used to spread misinformation, broadcast hate speech, and incite violence.

The role of social media has been documented as interacting and co-creating narratives with mass media in contexts of conflict. We understand mass media as a diverse set of media platforms that use mass communication to reach a large audience and operate within visible organisational structures. Platforms such as radio, television, newspapers, and magazines are examples of mass media. We define social media as decentralised broadcasting platforms that allow users to create and share content as well as engage in social networking. Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are examples of social media platforms.

The role of social media and its interaction with mass media in relation to conflicts remains a growing area of study, particularly after the Arab Spring.[2] The Arab Spring highlighted the importance of social media in social mobilisations leading to uprisings and the emergence of armed conflicts. It illustrated how conflicts and even armed action can be coordinated via social media platforms (as in Syria and Iraq). Despite this, the role of social media and its interaction with mass media in fuelling tensions across ‘ethnic’ groups in armed conflicts remains an under-researched area. Thus, while social media and mass media appear ubiquitous, little research has been conducted to examine how traditional mass media and social media interact in fuelling ethnic conflict.

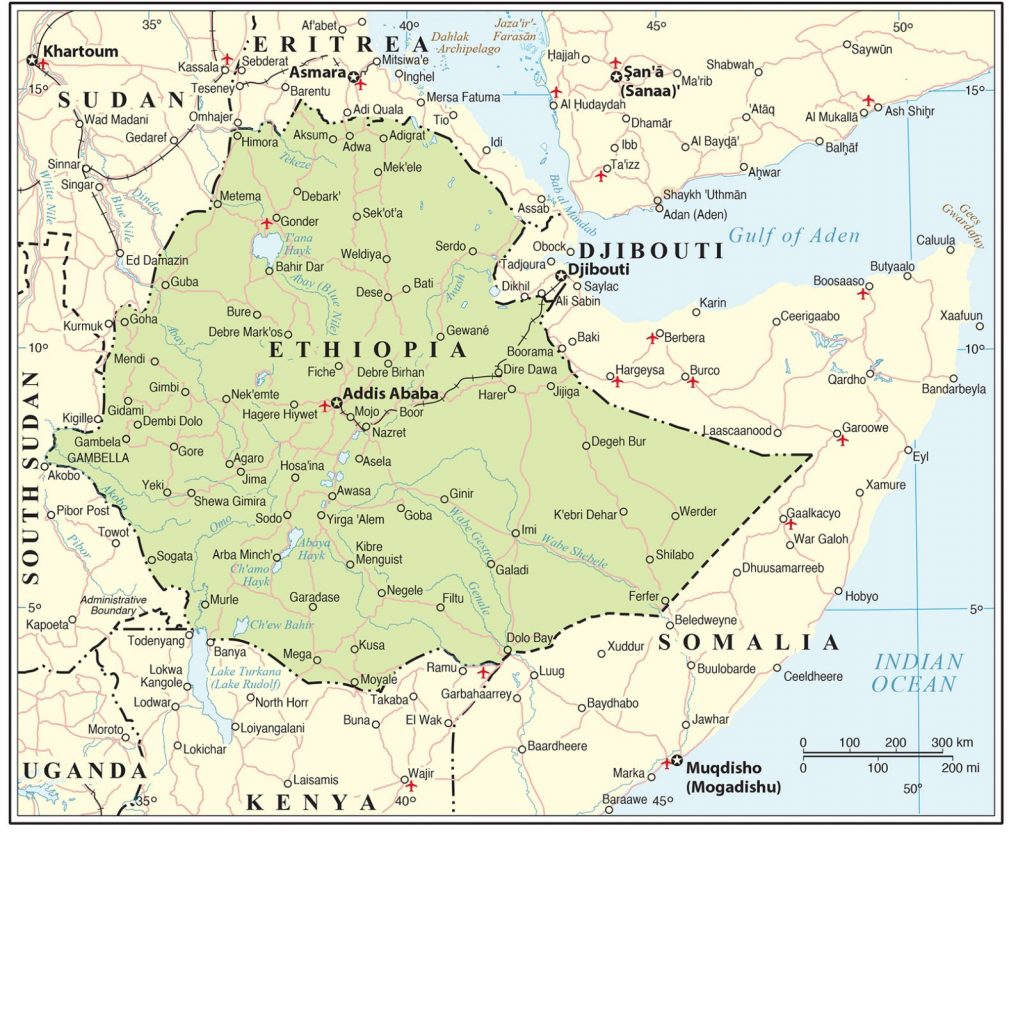

The armed conflict in Ethiopia in 2020 presents a more recent example of the interaction of both forms of media in exacerbating conflicts in relation to ethnic factors. While the conflict relates to a long history of tensions, there are serious risks of armed violence being systematically deployed on a larger scale against civilians and along ethnic lines. Expressions of violence directed against particular groups have been effected by the different contending armed actors in the current and previous conflicts. However, the increase in violence against specific groups and the explicit incitement of violence against different ethnic groups via social media and mass media are worrying developments.

Social media is a tool with incredible reach and self-selection mechanisms. This allows not only the deployment of marketing, but of more effective propaganda, which can inflame hatred and fuel conflict at a fraction of the cost of other propaganda tools.[3]Social media platforms are being misused by exploiting their shortcomings in controlling the spread of hate speech, misleading information, and incitement to violence. This is especially true of social media platforms in languages other than English, which are particularly susceptible to such misuse given the limited moderation of social media hate speech and false news. It is concerning that some political actors publish hate speech, false narratives, and misleading information on social media as mass media platforms. For example, the narratives used in Brexit or the discourses inciting armed violence at the Capitol Building in the United States (US) were both deployed through social media.

This article discusses the interaction between mass media and social media in conflict contexts and the risk associated with normalising hate speech. It does so by examining the case of the ongoing conflict and ethnic tensions in Ethiopia. The article begins by presenting the context for the emergence of armed conflict in Ethiopia in 2020, and then it examines the role of social media and mass media in fuelling tensions. Finally, the article discusses the centrality of social media in ongoing and future armed conflicts.

The Tensions Leading to Armed Conflict

The underlying causes of Ethiopia’s current armed conflict are linked to what is known as ‘the nationalities question’, which has been a major point of contention for Ethiopian central governments since Emperor Menelik II (1889-1913) established modern Ethiopia in the late nineteenth century.[4] Following the expansion of the Ethiopian State to include most present-day southwestern, southeastern, and southern territories, the emergence of modern Ethiopia involved the cultural, political, and economic subordination of different nationalities. The failure of successive regimes to implement policies aimed at integrating newly incorporated ethnic groups into the centre of power has informed the grievances and tensions that emerged with the proliferation of nationalist movements. This calls into question the concept of a single Ethiopian nation, as well as Ethiopian nationalism.

After the overthrow of the military regime in 1991 by a coalition of various ethnic-based armed groups, the nationalities question was addressed in the 1995 Constitution, which granted the various nationalities of the country the unconditional right to self-determination, including the right to secession (Federal Constitution, Art. 39(1)).[5] This provision was framed within an ethnic-based federal system that hoped to put an end to authoritarian and centralised governance structures, while strengthening representation within various ethnic groups.

However, disagreements remained over the role of the ethnic federal system in resolving the nationalities question after 1995. Opponents of the federal system argue that the federal model did not help resolve the nationalities question, but rather exacerbated ethnic tensions, and that the very foundations of national unity and territorial integrity could be eroded. Supporters of the ethnic-based federal system, on the other hand, claim that the governance system does not provide regions with meaningful autonomy and power over political and economic decisions. The latter group advocated for greater regional autonomy, and they were the main driving force behind protests in the Oromia region, which resulted in a government change and Abiy Ahmed Ali coming to power in 2018. Abiy faced the difficult task of balancing the demands of groups that supported the ethnic federal system (for example, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)) and those who opposed it (mainly the Amhara and urban elites).

In the era of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), political parties that were not organised along ethnic lines were pushed out of the political space and were vilified as supporters of the hegemonic old empire. The EPRDF also successfully pushed out its challengers among ethnically organised political parties, including the OLF, by labelling them ‘terrorist’ organisations. Similar tensions surfaced after Abiy took power in 2018.

Abiy initially enjoyed considerable support from the TPLF, as seen in his re-election as Prime Minister in October 2018. The conflict emerged after several prominent former-TPLF members were imprisoned in connection with different corruption scandals. The TPLF leaders argued that Abiy’s anti-corruption efforts were manipulated to target Tigrayans. These tensions escalated with the formation of a new political coalition, the Prosperity Party, at the end of 2019 and the TPLF’s refusal to join the new party, claiming that the process of dissolution of the EPRDF was unconstitutional. The TPLF and other political parties opposed the formation of the Prosperity Party, claiming that it would consolidate the central government’s power and erode the existing ethnic federal structure and the power of parties representing the interests of different ethnic groups. Tensions mounted with the postponement of the elections in 2020 and reached their zenith in the emergence of the war in the Tigray region in November 2020, following an alleged attack by TPLF forces on an Ethiopian army base in northern Tigray.

The Risk of Social Media and Mass Media Fuelling Ethnic Violence

The role of social media and mass media in fuelling tensions emerged before 2020. Different political groups have used mass media to push their narrative that other groups are a threat to the unity and continuation of the country following tensions around the shape of the State, leading to a highly polarised political environment. Social media further interacted with the political context and pre-existing tensions. It also interacted with the structure and the nature of the broadcasting landscape in Ethiopia.

Ethiopia has a history of a lack of independent media, a legacy of the Derg regime which followed a communist model of State-centralised information. The transition away from the Derg regime after the 1990s brought several changes, but the symbiosis between the State and media outlets continued. As a result, the State continues to have a strong hold on mass media outlets via its control and influence over mass media broadcasting channels. Despite being classified as public broadcasters, official media outlets, such as the Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation (EBC), the Ethiopian News Agency, and other outlets, are thus mainly used to support the central government’s communication strategy.[6]

This is why, during the early stages of the conflict, the Ethiopian government was extremely effective in establishing a media blackout. The imposition of a media blackout in the areas where clashes occurred made it difficult to report on the armed conflict beyond what was broadcast by government-controlled media outlets. Therefore, when federal forces claimed victory in July 2021, the claim was not contested. The gradual discovery of the Eritrean forces’ involvement in human rights abuses, as well as the advancement of Tigrayan forces into the neighbouring Amhara and Afar states during 2021, illustrates the dissonance between the claims of the government and the reality faced by civilians caught in the crossfire.

In this context of armed conflict and skewed representation of facts by the government and other warring parties, social media plays a central role in reinforcing or incepting new narratives. While Internet access is available to only around 25% of the population,[7] the role of social media has become extremely important and visible in the ongoing conflict. Social media is an important tool to access information given the media blackouts. Not only have social media platforms been used to denounce human rights abuses in Ethiopia, but they have also become a tool that allows different armed actors to create, influence or reinforce narratives of events associated with the armed conflict.

The importance of social media and its capacity to influence mass media and narratives of the conflict is illustrated by the developments following the announcement by the Tigray Defence Force (TDF) and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) of the capture of the strategic cities of Dessie and Kombolcha (about 260 km from Addis Ababa) in 2021. After these announcements, rumours quickly spread on social media claiming that the federal forces were defeated due to the role of Tigrayan civilian ‘sleeper cells’ in providing information to the TDF.

Following these rumours, civilians of Tigrayan origin living outside of Tigray were labelled ‘sleeper cells’ on many social media channels. Such allegations are also being used, albeit to a lesser extent, to demonise civilians of other ethnic origins, such as the Oromos. It is in this context that some social media influencers openly discussed the possibility of executing all Tigrayans, while others on social media have called for Tigrayans to be in internment, similar to the US concentration camps for Japanese Americans.[8]

These narratives have been endorsed by high-ranking government officials who stated that there are sleeper cells in many parts of the country. For example, Daniel Kibret, the Prime Minister’s Social Advisor, stated that federal forces lost in Dessie and Kombolcha because ‘there are a large number of traitors in these areas when compared to other regions’.[9] Such narratives are widely disseminated not only on social media, but also through government-affiliated mass media outlets (including television) that report the statements of politicians, thereby legitimising the messages generated on social media.

Social media and mass media have also co-created narratives that justify action against certain groups in the conflict, such as the mass arrest of Tigrayans living in Addis Ababa and other cities following the accusations about the existence of sleeper cells.[10]The arrest of Ethiopians of Tigrayan origin took place after media personality Mesay Mekonnen used Facebook to request that the government intern all Tigrayans.[11]

The interaction between social media and mass media is bidirectional as the government has used social media to broadcast messages after the declaration of a state of emergency. Following the declaration, the slogans ‘አካባቢህን ጠብቅ’ [Watch your neighbourhoods], ‘ወደ ግንባር ዝመት’ [Join the military], and ‘መከላከያን ደግፍ’ [Support the military] have been broadcast through the mass media and on social media daily. The announcement of a new social media platform just for Ethiopians to be developed by the government[12] illustrates that social media is not a neutral platform in the context of armed conflict. It is also not seen as such by parties who use social media as a tool to stigmatise civilians from different ethnicities as potential suspects and incite violence along ethnic lines.

The Centrality of Social Media Platforms in Armed Conflict

An empirical examination of the relationship between communication technologies and political violence in 24 African countries revealed that the expansion of social media is associated with an increase in the incidence of collective violence.[13] One possible explanation for these empirical findings is that the expansion of social media allows for the reinforcement of identarian discourses, making divisive rhetoric and social segregation easier to produce.

While there is a greater understanding of the role of social media in facilitating violent acts, social media platforms continue to fail to identify and block incitements to violence in a timely manner. This is especially problematic in the case of non-English languages. In Ethiopia, social media is used to promote violence openly, such as the elimination of various groups. This is extremely dangerous in a civil war because the conflict has the potential to escalate into mass atrocities and genocide.[14] The case of Ethiopia also highlights the need for conflict researchers to look at the interaction between social media and mass media and their role in fuelling narratives that are used to justify or incite violence against civilians.

Although some social media platforms are now removing some of these messages inciting violence and blocking some of the accounts for spreading hate speech after the denunciation by several actors, the original posts in Amharic have already been widely shared across various platforms (for example, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Telegram). This is, therefore, not only a problem of enforcement, but also a problem of moderation on social media channels. In fact, community standards for social media platforms, such as Facebook, are not available in Amharic and other major languages in Ethiopia, making enforcement even more difficult.

There is limited effort by social media companies to take responsibility for the use of social media platforms as a tool for inciting violence, under the argument that those inciting violence are the users of such platforms and not the platforms themselves. Social media tools are products, and as such, their creators should be held accountable. While it is difficult to predict how actors intend to use social media to incite violence, companies’ inaction to curb the incitement of violence is also analogous to plane manufacturers being warned of unsafe planes and failing to take corrective action.

Aside from social media companies, governments bear responsibility for the development of policies aimed at promoting social cohesion, combating hate speech, and protecting vulnerable groups during conflicts. While Ethiopian lawmakers enacted the Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention and Suppression Proclamation in March 2020, many individuals and government-related organisations that posted hate speech have not faced repercussions, despite inciting violence.[15]

A need remains to understand the role of governments in incepting narratives that lead to tensions. This has been observed in other armed conflicts before the emergence of social media, for example, in the Rwandan genocide. Yet in a context in which media (social and mass) is mostly controlled by the State, as in Ethiopia, there is the inescapable outcome that these tools will serve the discourse and the narrative that the State chooses to wield, whether it is a discourse of reconciliation or of violence and hatred. In such cases, even when social media platforms aim to protect their users from hate speech, they will hardly be able to outweigh the messages of a State, especially when the State aims to have its own social media platform.

Conclusion

Conflicts, whether armed or nonviolent, are connected to the societies in which they take place. This highlights the importance of reflecting on the cultural and technological aspects informing the way armed conflicts unfold. The case of the ongoing armed conflict in Ethiopia since 2020 illustrates the interaction between mass media and social media, and the role of recent media platforms in armed conflict. Technology is not bad or good per se; its effects depend on how technology is acted upon by different actors. The case of Ethiopia illustrates how the pernicious feedback between social media and mass media can fuel ethnic tensions via hate speech and narratives that justify violence along ethnic lines.

Hate speech and violence justifying narratives within armed conflicts are not new; however, the way in which they are being deployed operates via new channels and platforms. The transition from newspapers, television and radio to broadcasting violence-inciting narratives via memes, YouTube videos, WhatsApp message chains, and Facebook posts illustrates this.

Mass media and social media connect State and society. The case of Ethiopia highlights the need for conflict and peace researchers to examine the interaction between social media and mass media. The role of social media in influencing mass media and the different narratives associated with conflict is an area of research that needs more attention from conflict researchers and peacebuilders across the globe. Whether it be the escalation of violence or the promise of peace, social media will continue to be central in the Ethiopian conflict and other conflicts across the world.

Dr Muna Shifa is a Senior Research Officer in the Southern Africa Labour Development Research Unit (SALDRU) at the University of Cape Town, South Africa and part of the editorial board of the journal Scientific African.

Fabio Andrés Díaz Pabón is a Researcher at the African Centre of Excellence for Inequality Research (ACEIR) at the University of Cape Town and a Research Associate at the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University, South Africa.

Endnotes

[1] Kubin, Emily and von Sikorski, Christian (2021) ‘The Role of (Social) Media in Political Polarization: A Systematic Review’, Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(3), 188-206.

[2] Adeyanju, Collins (2018) ‘The Mass Media and Violent Conflicts in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Journal of Liberty and International Affairs, 4(3), 73-87.

Tarrow, Sidney (2011) Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3] Shani, Ayelett (2019) ‘Just Think What Goebbels Could Have Done With Facebook’, Available at: <https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/.premium.magazine-just-think-what-goebbels-could-have-done-with-facebook-1.7308812> [Accessed 19 November 2021].

[4] Keller, Edmond (1981) ‘Ethiopia: Revolution, Class, and the National Question’, African Affairs, 80(321), 519-549; Gudina, Merera (2003) ‘The Elite and the Quest for Peace, Democracy, and Development in Ethiopia: Lessons to be Learnt’, Northeast African Studies, 10(2), 141-164.

[5] Republic of Ethiopia (1995) ‘Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia’, Negarit Gazeta, Proclamation No. 1/1995, Available at: <https://ethiopianembassy.be/wp-content/uploads/Constitution-of-the-FDRE.pdf> [Accessed 18 November 2021].

[6] Skjerdal, Terje and Moges, Mulatu Alemayehu (2021) ‘The Ethnification of the Ethiopian Media’, Fojo Media Institute and International Media Support, Available at: <https://fojo.se/en/new-study-documents-ethnification-of-the-ethiopian-media-2> [Accessed 18 November 2021].

[7] World Bank (2021) ‘Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population) – Ethiopia’, Available at: <https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/it.net.user.zs?locations=ET> [Accessed 18 January 2022].

[8] Weldemichel, Teklehaymanot G. (2021) ‘Here is an Example of One of the Fruits of

@AbiyAhmedAli Calls for Violence Against Ethnic Tigrayans in Ethiopia’, Available at: <https://twitter.com/TeklehaymanotG/status/1456615138874757122> [Accessed 19 November 2021]; Adebabay Media (2021) ‘LIVE: ልዩ ዝግጅት|| የውስጥ አስተኳሾች፣ ያሸለቡ ሰላዮች (Sleeper cells) እና የህልውና ጦርነቱ ፍጻሜ || ሌሎች ከተሞች ከደሴ ምን ይማራሉ?’, Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mj_Z4qUEnzI> [Accessed 19 November 2021].

[9] Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation (2021) ‘ቀይ መስመር- አካባቢህን ጠብቅ፣ ወደ ግንባር ዝመት፣ መከላከያን ደግፍ’, Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jkcLrY0rgHI&t=2678s&ab_channel=EBC> [Accessed 19 November 2021].

[10] Addis Standard (2021) ‘Arrests in Connection with SoE Appear to be “Identity-based” Rights Commission Says’, 8 November, Available at: <https://addisstandard.com/news-arrests-in-connection-with-soe-appear-to-be-identity-based-rights-commission-says> [Accessed 18 January 2022]

[11] This post has since been deleted on Facebook. See Sir Arwa (2021) ‘Report the Following Posts/Users on @Facebook IMMEDIATELY. These are Credible Threats to Incite Mass Violence Against Civilians. They are Literal Calls for Genocide’, Available at: <https://twitter.com/sirarwa/status/1454621941294317569> [Accessed 18 January 2022].

[12] Reuters (2021) ‘Ethiopia to Build Local Rival to Facebook, Other Platforms’, 23 August, Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/ethiopia-build-local-rival-facebook-other-platforms-2021-08-23> [Accessed 17 November 2021].

[13] Warren, T. Camber (2015) ‘Explosive Connections? Mass Media, Social Media, and the Geography of Collective Violence in African States’, Journal of Peace Research, 52(3), 297-311.

[14] According to the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission (EHRC), a state of emergency gives blanket powers to law enforcement with the right to detain individuals who are allegedly working with the TPLF and OLA. So far, the EHRC lacks information on the exact number of detainees and their conditions. The individuals arrested were largely Tigrayans and most arrests were made because of tip-offs from informants or vigilante groups on the lookout for suspects. The Commission voiced concern over the arrests, saying that insufficient attempts were being made to establish that the claims are not linked to racial profiling and whether there were reasonable concerns. In addition, some social media ‘activists’, such as Dejene Assefa, have gone as far as explicitly stating who should be targeted, using phrases like ‘the war is with the one who has been your neighbor for ages and is with you and your people and is waiting for your death’. See Plaut, Martin (2021) ‘Ethiopian Hate-speech Worthy of the Rwandan Genocide Carried by Facebook’, Eritrea Hub, 31 October, Available at: <https://eritreahub.org/ethiopian-hate-speech-worthy-of-the-rwandan-genocide-carried-by-facebook> [Accessed 25 January 2022].

[15] Knight, Tess and Alexion, Beth (2021) ‘Influential Ethiopian Social Media Accounts Stoke Violence Along Ethnic Lines’, Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), Available at: <https://medium.com/dfrlab/influential-ethiopian-social-media-accounts-stoke-violence-along-ethnic-lines-6713a1920b02> [Accessed 18 January 2022].