The coronavirus has forced the African Union (AU) and the United Nations (UN) to develop new adaptive contingency plans for their peace operations. Among others, these plans identify which activities need to be carried out, despite COVID-19, to meet mandated responsibilities. These typically include support to peace processes, patrols and activities related to stabilisation and the protection of civilians, convoy escorts and other forms of support to humanitarian assistance, force protection, protecting key infrastructure, and support to host state institutions and local authorities. These essential activities had to be adapted to minimise the risk of spreading the virus to both the people the UN is tasked to protect and to the peacekeepers themselves.1

It is important not to associate essential activities only with military activities, such as armed escorts. Many of the activities that distinguish multidimensional peace operations from other international military operations include its civilian capacity to support political processes, to create conditions conducive for protection, to support the negotiation of local peace agreements, to observe and promote human rights and to support national, regional and local government capacities. Some of these civilian functions are still being carried out, but most of them are now done remotely. All of these activities have to be planned, financed, managed, coordinated, supported and assessed, and these functions are also carrying on.

Most civilian and uniformed headquarters staff are working from their homes or mission accommodation, and approximately 10% of international civilian staff are now working from outside the mission area. This means that almost all of the planning and support work is now being done electronically, including via video-teleconferencing, and this has forced the AU and UN to adopt or speed up the implementation of digital approval and related processes. One of the unintended consequences is a loss of national staff input, which is critical in several areas, because many do not have internet connectivity at home. Missions are addressing this challenge by increasing mobile connectivity to their systems. These developments will modernise the way the AU and UN utilise technology and change some headquarters functions in the future.

Not everything can be done remotely, however. Negotiation over the phone can only take you so far. One of the great assets of field staff has been that they can get into a car, drive to a location, track down an important interlocutor and obtain important information or come to an agreement with them on what actions will be taken – for instance, to protect civilians. In some contexts, mounted patrols without social interaction do not have the same effect as dismounted patrols. It is thus impossible to expect that peace operations will have the same overall impact today than they had before the COVID-19 crisis.

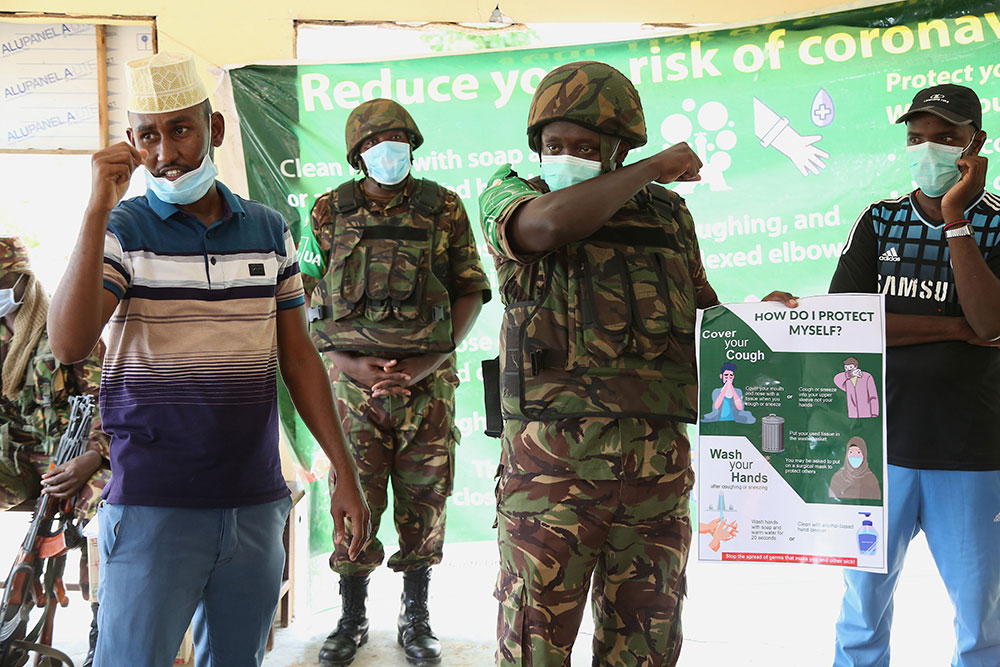

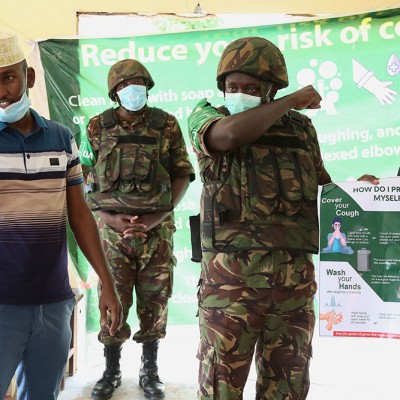

In the short term, peace operations also have to manage a number of other challenges. In some countries, there are fears, rumours and perhaps even active disinformation campaigns that foreign peacekeepers are responsible for spreading the virus. In South Sudan, for instance, government forces have put up checkpoints outside

UN compounds in several locations to stop or reduce UN movements.2 These actions have also impacted on the approximately 150 000 people sheltering in civilian camps under UN protection.3 The AU and UN have had to manage similar fears and rumour-mongering in Central African Republic (CAR),4 the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Mali and Somalia. Missions have to grapple with questions such as whether troops should wear masks to reassure the population, or whether wearing masks in situations where that is not the norm among the population will only increase such fears and rumours. UN radio stations such as Radio Guira in CAR, Radio Okapi in the DRC, Radio Mikado in Mali and Radio Miraya in South Sudan are helping to share accurate information about the coronavirus in local languages. Peace operations are increasing the reach of these stations by handing out solar and wind-up radios to remote local communities that do not have access to electricity or the internet.

One of the priority areas for AU and UN peace operations is supporting host authorities and communities. Quick impact projects and programmatic funding have been repurposed to help local institutions and communities prepare for and cope with the virus. In CAR, the DRC and elsewhere, missions are scaling up support for local mask production by women’s grou

To reduce risk to host populations and peacekeepers alike, the AU and UN have frozen all rotations until 30 June 2020. Among the approximately 100 000 soldiers and police officers currently deployed, approximately 40% are due to be rotated home and to be replaced in the next few months. There will thus be significant demand in July and August on the available airlift capacity and logistical personnel. All new troops rotating in will go into 14 days of quarantine, which poses another logistical challenge. It also means they cannot be operational over this period, which increases the workload on the rest of the units.

The most severe disruption to AU and UN peacekeeping is likely to be caused by another side-effect of the COVID-19 crisis: a global economic recession. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has changed its forecast for 2020 from a 3.3% growth to a 3% contraction in the global economy.5 The United States, which is one of the countries most affected by the virus, is also the largest financial contributor to the UN peacekeeping budget. Many of the more than 120 countries that have contributed peacekeepers in the past – including big contributors such as Ethiopia, Rwanda, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Senegal6 – may also come under domestic pressure to reduce troop numbers for financial or coronavirus risk-related reasons.

In the medium term, the AU and UN may thus be faced with a situation 12 to 18 months from now where UN peacekeeping operations have significantly less capacity than they do today. It is unlikely that the risk to civilians in these situations will change significantly for the better in the short to medium term.7 The more likely scenario is that the effects of the coronavirus, coupled with other factors such as climate change, will increase instability and risk.8 The most critical risk is stalled political processes. The response to the UN Secretary-General’s call for a global ceasefire – which has been echoed by the AU chairperson9 – has been mixed, and in some cases, fighting has increased. In others, COVID-19 is the new shared enemy that is creating new alliances. The burden on AU and UN peace operations will only increase. On the one hand, missions are under increasing pressure to improve the effectiveness of their operations,10 whilst on the other, they have to cope simultaneously with shrinking budgets and even more complex operational environments, further constrained by the coronavirus and climate change.

In the next few months, the UN’s Fifth Committee will consider the peacekeeping budget for the next financial year.11 Hopefully, the UN’s member states will show the same agility that missions have demonstrated over the past couple of weeks, as missions will need flexibility as they continue to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances in the coming months.

Thus far, Africa, where the bulk of AU and UN peacekeepers are deployed, has been spared the brunt of the crisis, but this is likely to change in the medium term.12 The AU and UN headquarters, and their respective peace operations, have demonstrated remarkable resilience in the way they have coped with and adapted to the crisis.13 Some of the new innovations and practices that have emerged in this process are specific to the virus, and will change over time in response to the severity of the risk the virus poses. Others are likely to be more lasting, including a more essential-scale approach to mandate implementation and a more adaptive approach to planning and mission management. The most dramatic change, however, is likely to be a significant reduction in funding and troops over the medium term as peace operations contract in lockstep with the global economy.

Cedric de Coning is a Senior Research Fellow with the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Senior Advisor for ACCORD and Coordinator of the Effectiveness of Peace Operations Network (EPON). He tweets at

@CedricdeConing.

Endnotes

- De Coning, Cedric (2020) ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Peace Operations’, IPI Global Observatory, 2 April, Available at: <https://theglobalobservatory.org/2020/04/impact-covid-19-peace-operations/> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Anyadike, Obi (2020) ‘Briefing: What’s Behind South Sudan’s COVID-19 Inspired UN-backlash’, The New Humanitarian, 10 April, Available at: <https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news/2020/04/10/south-sudan-UN-coronavirus-backlash> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Wote, Charles and Okuj, Obaj (2020) ‘Army Allegedly won’t Allow IDPs to Exit Malakal Poc’, Eye Radio, 8 April, Available at: <https://eyeradio.org/army-allegedly-wont-allow-idps-to-exit-malakal-poc/> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Losh, Jack (2020) ‘Foreigners Targeted in Central African Republic as Coronavirus Fears Grow’, The Guardian, 10 April, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/10/foreigners-central-african-republic-coronavirus-fears-grow> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Elliot, Larry (2020) ‘“Great Lockdown” to Rival Great Depression with 3% Hit to Global Economy, Says IMF’, The Guardian, 14 April, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/apr/14/great-lockdown-coronavirus-to-rival-great-depression-with-3-hit-to-global-economy-says-imf >[Accessed 22 May 2020].

- United Nations Peacekeeping (2020) ‘Troop and Police Contributors’, Available at: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/troop-and-police-contributors> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- ACCORD (2020) ‘COVID-19 & Conflict’, Available at: <https://accord.org.za/covid-19/> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- International Crisis Group (2020) ‘COVID-19 and Conflict: Seven Trends to Watch’, ICG, 24 March, Available at: <https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/sb4-covid-19-and-conflict-seven-trends-watch> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Gutteres, António (2020) ‘To Silence the Guns, We Must Raise the Voices for Peace’, Available at: <https://www.un.org/en/un-coronavirus-communications-team/update-secretary-general%E2%80%99s-appeal-global-ceasefire> [Accessed

22 May 2020]. - EPON (2020) ‘The Effectiveness of Peace Operations Network’, Available at: <https://effectivepeaceops.net/> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- United Nations (2020) ‘Overview of the Financing of the United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Budget Performance for the Period from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019 and Budget for the Period from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021’, Available at: <https://undocs.org/A/74/736> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Dwyer, Colin (2020) ‘U.N. Agency Fears “Vulnerable” Africa may Suffer at Least 300,000 COVID-19 Deaths’, NPR, 17 April, Available at: <https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/17/836896562/u-n-agency-fears-vulnerable-africa-may-suffer-at-least-300-000-covid-19-deaths?t=1588308708484> [Accessed 22 May 2020].

- Khare, Atul and Lacroix, Jean-Pierre (2020) ‘UN Peacekeepers Must Stay the Course’, IPI Global Observatory, 23 April, Available at: <https://theglobalobservatory.org/2020/04/un-peacekeepers-must-stay-the-course/#more-20288> [Accessed 22 May 2020].