The partnership is underpinned by the twin principles of subsidiarity and complementarity.2 Although the RECs/RMs are not uniform entities, it is well established that neither the AU nor the UN can undertake a successful peacemaking venture without the active involvement of the dominant REC/RM in a particular sub-region. For example, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s (IGAD) pivotal role in the mediation efforts that led to the signing of the Revitalised-Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) is the most recent demonstration of this trend.3 Similar examples exist in West, Central and southern Africa, where the RECs/RMs in these sub-regions continue to serve as anchors for security and stability.

Background

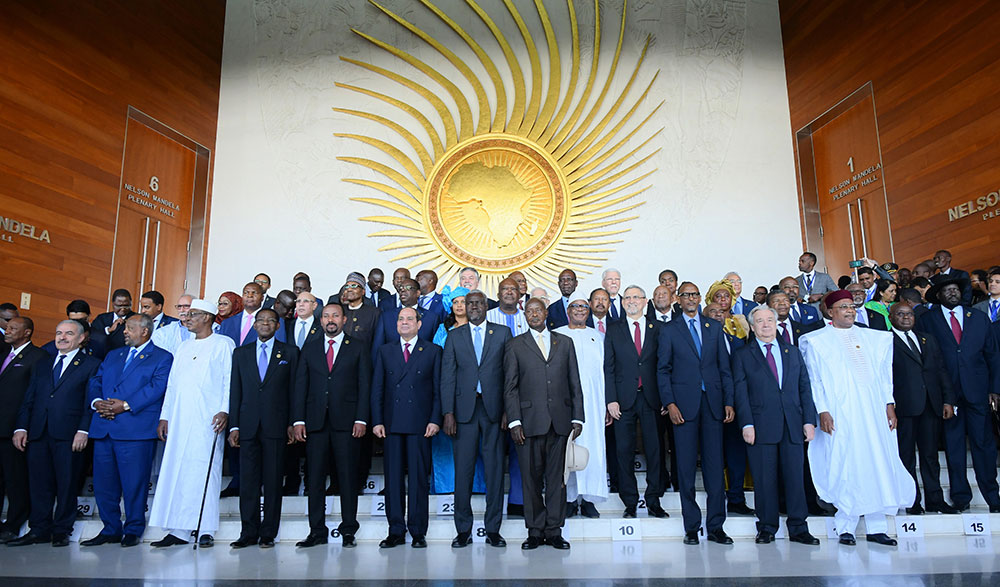

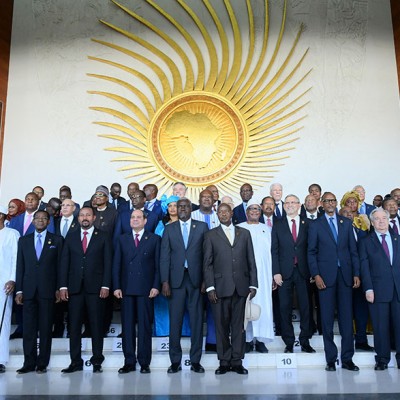

The 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), in May 1963, was an occasion to reflect on the accomplishment of the OAU and to chart a new path for the continent. At the conclusion of their deliberations during the 21st Ordinary Summit of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, African leaders adopted the 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration in which they committed to achieving a conflict-free Africa and, more critically, “…not to bequeath the burden of conflict to the next generation of Africans and undertake to end all wars in Africa by 2020.”4 In furtherance of the Solemn Declaration, a retreat of the AU Peace and Security Council (AUPSC) in Lusaka, Zambia, developed an AU Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by Year 2020 (AUMR), which was subsequently endorsed by the 28th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union.5 The AUMR has five categories: political, economic, social, environmental and legal. Moreover, it identifies a number of challenges or scourges, ranging from the persistence of political denials in situations of brewing or potential crises and deficits in respect for human rights to the illicit flow of weapons that are fuelling conflicts on the continent. The AUMR also enunciates the practical steps, modalities for mobilising action, focal points/implementers, time frame and sources of funding for the achievement of the objective set out in the 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration.

Both the Solemn Declaration and the AUMR emphasised the need to strengthen Africa’s voice in the international system through improved cooperation between the AU, RECs, UN and other multilateral institutions. It is in this context that this article reflects on how the partnership between the AU and RECs/RMs at one level, and that between the AU and UN – a two-tier cooperation model – can be leveraged to foster Africa’s efforts at silencing the guns. The article is divided into four sections: normative convergence, conflict prevention and management, peace support operations, and peacebuilding/stabilisation.

1. Normative Convergence

The proactive engagement of the OAU (which transitioned into the AU in 2002) and the RECs/RMs as key actors in the 1990s signalled a growing determination by African states to take charge of peace, security and stability on the continent. The current posture of the AU and RECs/RMs can be attributed to two key post-Cold War developments. First, the removal of the superpower overlay exposed the deep political, security and socio-economic fault lines that had been suppressed due to competition by the superpowers. Second was the indifference of the international community to the violent conflicts that engulfed parts of the continent in the early 1990s – most notably, the genocide in Rwanda, the implosion of the countries of the Mano River Basin, the collapse of Somalia and the conflicts in the Great Lakes region. These experiences triggered a normative shift in Africa’s international relations. The shift from non-interference in the internal affairs of member states to non-indifference has resulted in the development of robust norms that are anchored on the principle of shared values. The Constitutive Act of the AU and the respective legal instruments of the RECs provide for the setting up of decision-making organs and implementation mechanisms on peace and security. The establishment of the AUPSC in 2004 is the most notable development in this respect. At the sub-regional level, individual RECs/RMs have established similar decision-making organs.

It should be noted that the establishment of the peace and security architectures of the AU and RECs/RMs is consistent with Article 52(1) of the UN Charter, which provides for the “existence of regional arrangements or agencies for dealing with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security as are appropriate for regional action…”6 However, the normative shift in Africa conflicts with certain parts of the UN Charter, given that the AU can intervene in a country in situations involving serious crimes. For instance, Article 4(h and j) of the Constitutive Act provides for intervention including the use of force in situations of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide, without necessarily waiting for the authorisation of the UN Security Council (UNSC).7 This provision contradicts Article 53(1) of the UN Charter, which states that “no enforcement action shall be taken under regional arrangements or by regional agencies without the authorization of the Security Council.…”8

Given the deadlocked nature of the UNSC due to competition between its veto-wielding members, among other things, strict adherence to Article 53(1) could hamper efforts by the AU and RECs/RMs to silence the guns because their efforts could be stymied by discord between the five permanent members of the UNSC.9 This therefore calls for a flexible application of Chapter VIII of the UN Charter, and leveraging of the principle of subsidiarity to avoid obstructing the actions of the AU and RECs/RMs in situations where the UNSC is deadlocked.

Subsidiarity and Complementarity

Indeed, the imperative for subsidiarity and complementarity was not lost on the two African Secretaries-General of the UN in the post-Cold War era, Boutros Boutros Ghali and Kofi Annan. They strongly advocated for the flexible application of Chapter VIII of the UN Charter to optimise the synergy between the UN and the emerging actors on the continent. For its part, the leadership of the AU Commission, starting with then-chairperson Alpha Omar Konare, took decisive steps in defining the AU–UN partnership with a view to strengthening the capacities of the AU and, by extension, the RECs/RMs as first respondents. The signing of the Enhancing UN-AU Cooperation: Framework for the Ten-year Capacity Building Programme for the AU by Chairperson Konare and then-Secretary-General Annan, in November 2006, was the first important step in laying the foundation for the relationship. This was followed by several reports on partnerships between the AU and UN on peace and security, which culminated in the current Joint African Union–United Nations Framework for Enhanced Partnership in Peace and Security.10 These efforts were informed by the imperative to harness the comparative strengths of the UN, AU and, by extension, the RECs/RMs. In other words, the evolving agreements over the past two decades have moved the AU-RECs/RMs and UN closer to an effective application of subsidiarity and complementarity for a more enhanced multilateral peacemaking system, in Africa.

At another level, the ongoing process of defining a division of labour between the AU and the RECs/RMs, as part of the overall institutional reform of the AU, is a crucial development that would impact the nature and scope of the triangular partnership. In November 2018, the Executive Council of the AU “mandated the AU Commission in collaboration with the RECs/RMs, AU organs, relevant continental organisations, to develop a proposal on an effective division of labour among the AU, the RECs/RMs, the Member States, and other continental institutions, in line with the principle of subsidiarity….”11 This matter was subsequently discussed during the First Mid-Year Coordination Meeting of the AU and the RECs/RMs, held in Niamey, Niger, in July 2019. The declaration of the coordination meeting called on the AU Commission, in collaboration with the member states, RECs/RMs, AU organs and regional mechanisms, to “operationalize the framework on an effective division of labour”.12 Under the envisaged system, the AU would devolve some of its key peace and security responsibilities to the RECs/RMs.

This undoubtedly has raised critical questions for the triangular partnership, especially that between the AU and the RECs/RMs. For instance, how would the division of labour between the AU and RECs affect the pre-eminence of the PSC on continental security matters? What mechanisms should be put in place to regulate the relationship between the AU and RECs/RMs? What safeguard measures should be instituted to ensure that the principle of subsidiarity is not used by the RECs/RMs to exclude the AU in situations where the REC in question is hamstrung due to political or other considerations? How would this affect the AU’s relationship with the UN? Although these questions are not addressed in this article, it is critical to ensure that the partnership between the AU and the RECs/RMs is anchored on mutually agreed principles and well-defined coordination structures, especially between the PSC and similar structures at the level of the RECs/RMs. Doing so would contribute to optimising complementarity and coherence. Moreover, the arrangement between the AU and RECs/RMs should be reflected in the AU’s relationship with the UN to allow for a seamless application of a two-tiered system of subsidiarity, with the UN at the apex. The establishment of an interlocking system for the application of the principle of subsidiarity between the three entities would enhance efforts to silence the guns by minimising competition, scaling up cooperation and ensuring the prudent management of political capital and other resources.

2. Conflict Prevention and Management

There is consensus among the AU, RECs/RMs and UN on the imperative to invest in conflict prevention to avoid the high costs associated with violent conflict. Consequently, conflict prevention is at the heart of the strategies, policies, programmes and activities of the various entities involved in the triangular partnership. In fact, preventing conflict and sustaining peace is the first priority in the joint framework; the two other priorities being responding to conflict and addressing root causes. The AU and RECs/RMs have instituted various mechanisms to detect, prevent and manage conflicts. The African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) and the African Governance Architecture (AGA) are the two main instruments at the continental level, with complementing structures at the sub-regional level.

While the triangular partnership has registered some positive results since the signing of the framework agreement in April 2017, it has also encountered some challenges. The partnership between the AU, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and the UN during the peace talks in Khartoum, Sudan, between the Government of the Central African Republic (CAR) and the armed groups, is perhaps the most successful joint undertaking since the signing of the framework agreement. The mediation process that culminated in the signing of the Political Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation in the Central African Republic, on 5 February 2019, was led by AU and ECCAS, whilst the UN provided logistics and other backstopping support. The three entities are now fully engaged in supporting implementation of the various pillars of the agreement, ranging from national reconciliation, transitional justice to the establishment of the mixed military units. The partnership between the AU, ECCAS and UN during the CAR peace talks in Khartoum represents a near-perfect application of the principles of subsidiarity and complementarity, and such coordinated interventions would contribute to enhancing peace consolidation efforts in the country. The challenge now is how to ensure that this triangular relationship is leveraged to support the implementation of the agreement so that when the guns are silenced in CAR, they do not rebound, as in the past. In other words, avoiding a relapse should be a priority for all external actors, including the AU, ECCAS and the UN.

Unlike the CAR experience, in Libya, cooperation between the AU, UN and other actors has been suboptimal. This situation dates back to 2011, when the AU and UN failed to agree on how to respond to the crisis that had gripped Libya. Despite a series of meetings between the two organisations and conciliatory pronouncements by their leadership, the partnership remains fractious. The perceived marginal role of the AU in finding solutions to the Libyan crisis, which has exacerbated the security challenges in the Sahel, demonstrates that the application of the subsidiarity principle is problematic in situations where the P5 and other global powers have conflicting interests. Agreeing on a workable cooperation formula in this particular instance has remained elusive, for a couple of reasons. First, Africa and the P5 have been unsuccessful in reconciling their differences following the outbreak of the crisis in 2011. Second, the internationalisation of the conflict has weakened the chances of a multilateral approach to resolving it. Growing competition between international powers continue to exacerbate the crisis, further complicating peace efforts.

3. Peace Support Operations

Despite the challenges for the partnership in Libya, notable progress has been made on peace support operations. Interestingly, the UNSC and AUPSC have found common ground in this area, especially the AU–UN Hybrid Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) and the AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). The two councils have demonstrated creativity and flexibility in the management of these two missions. The use of assessed contributions for the provision of logistics support to AMISOM is the most prominent demonstration of what can be achieved when the councils are in harmony. However, even in this instance, there are some tensions regarding the division of labour between the UN, AU and IGAD in terms of the political process in Somalia. There is a perception by some that the AU should concentrate on the implementation of its peace support mandate, leaving the political track to the UN. Attempts to limit the AU’s role in the political process have created some friction between the two organisations. Efforts should be made to harmonise the two positions, as decoupling the military and the political process would undermine stabilisation efforts, given that peace support operations are not an end in themselves but a means to an end. The planned transition in Somalia, including the drawdown of AMISOM, presents a unique opportunity to leverage the partnership between the AU, IGAD and UN to consolidate the gains in Somalia. Sustaining peace in Somalia is central to silencing the guns in the Horn of Africa.

In Darfur, consultations are ongoing as part of the drawdown of UNAMID to agree on a workable formula for the post-UNAMID engagements. At the heart of the deliberations is whether the hybrid principle that shaped UNAMID should be retained in the new configuration. Whilst the AU favours such an arrangement, the UN is not enthusiastic about it. As was the case with the government of former president Omar al-Bashir, which insisted on the hybrid mission, the position of the transitional Government of Sudan would determine the form of the AU–UN engagement in Darfur.

How the transitions from peacekeeping/enforcement to peacebuilding in these countries are handled will determine the success and sustainability of peace in those theatres.

Despite the progress in the partnership between the AU and UN in Somalia and Darfur, how to respond to the challenges posed by terrorist and jihadi groups remain unresolved. Fundamentally, the challenge is the doctrinal gap relating to high-intensity operations. While the AU and RECs/RMs have demonstrated the will and capacity to undertake robust peace enforcement and counter-insurgency operations, the UN is unable to undertake similar missions due to doctrinal constraints.

The emergence of ad hoc military coalitions – such the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram and the G5 Sahel Joint Force – are major consequences of this challenge. Even within UN missions, the establishment of units with more robust mandates –

such the Force Intervention Brigade within the United Nations Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO) and proposals for similar structures in the UN Integrated Multidimensional Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) – demonstrate the urgency of tackling the doctrinal gap. The imperative to close this gap is informed by the growing need for more robust engagements against terrorist groups with no identifiable political agendas, thereby complicating any political engagements. While the ad hoc coalitions such as the MNJTF have proven to be effective, funding and logistics support – especially for the G5 Sahel Joint Force – remains a big challenge. To address this, the AU needs to intensify consultations with the UN and other key actors – most notably, the United States of America (USA) – on the use of the UN-assessed contribution for AU-led and UN-authorised missions. Efforts should also be made to consolidate the multidimensional capacities – notably, military, police and civilian – through the African Standby Force (ASF), which have been developed by the AU and the RECs/RMs over the past decade and a half.

4. Peacebuilding and Stabilisation

Managing transitions from peacekeeping to medium and long-term stabilisation is critical to silencing the guns and sustaining peace. Unfortunately, peacebuilding remains the single most important gap in the partnership between the AU, RECs/RMs and the UN. A close reading of the Joint Framework Agreement reveals this important lacuna in the partnership. While the AU has proactively engaged with RECs/RMs such as the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC) to develop a comprehensive strategy for a holistic revitalisation of the areas affected by the Boko Haram insurgency in the Lake Chad Basin, implementation of the Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery & Resilience of the Boko Haram-affected Areas of the Lake Chad Basin Region13 has been slow. At least three critical lessons can be drawn from the process of developing the stabilisation strategy. First is that the principle of subsidiarity was complied with, as the AU allowed the LCBC to lead the process. In doing so, the LCBC mobilised the political support of its members, thereby enhancing national ownership of the process. Second, the AU complemented the efforts of the LCBC with political and technical support, both of which were indispensable to the process. Finally, the strong partnership between the AU and LCBC strengthened their leadership role of the process, among other things by ensuring that the interventions of UN agencies and other stakeholders was in sync with the priorities identified by the two organisations. This goes to show that the AU’s partnership with the UN will be bolstered when the AU works closely with the RECs/RMs. In other words, the AU-RECs/RMs partnership is a force multiplier in the triangular cooperation framework.

How the AU, RECs/RMs and the UN system manages to generate the required financial and technical resources for the implementation of the stabilisation strategy will determine how soon the guns will be silenced in the Lake Chad Basin. Similar efforts are required for the transitions in Somalia, the CAR, South Sudan, the Great Lakes and Sahel regions. The development of comprehensive strategies, and generating the required resources for implementation, will be a critical step towards silencing the guns. At a global level, the 2020 review of the UN peacebuilding architecture presents a unique opportunity for Africa to articulate its peacebuilding priorities, which should be at the centre of its partnership with the UN system.

Conclusion

It is evident that the triangular partnership has yielded mixed results but holds a lot of potential for resolving some of the existing and emerging challenges on the continent. The strength of the partnership will be optimised if it is approached from a two-tiered lens: the partnership between the AU and the RECs on the one hand, and between the AU, RECs/RMs and the UN on the other. This will ensure that the AU and RECs/RMs maintain ownership and leadership of Africa’s peace and security agenda. Lessons from across the world have shown that homegrown peacebuilding and stabilisation initiatives are more resilient than externally driven ones. Consequently, efforts to silence the guns will be largely contingent on Africa’s commitment of the requisite political, financial and human resources for medium- to long-term stabilisation efforts. The UN, with its global mandate, should act in a complementary manner to the AU and RECs/RMs.

The two-tiered cooperation model advanced in this article will foster the objectives of silencing the guns, thereby achieving an important pillar of Agenda 2063.

Alhaji Sarjoh Bah, PhD, is the Chief Advisor: Peace, Security and Governance, to the African Union Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations.

Endnotes

- The views expressed here are those of the author only, and not the AU Permanent Observer Mission to the UN or the AU Commission. I completed this article at the height of the outbreak of the coronavirus, when we were in lockdown in New York City and the number of cases was increasing globally. The coronavirus reinforced our level of interconnectedness, and the imperative for partnerships and multilateralism. As we went to press, even the most powerful countries in the world were struggling to provide adequate, timely and effective responses to the pandemic. As I observed the response of the US government with its complex governance system, from my residence in New Rochelle, the epicentre of the virus in the US during the months of April, May and June, my conviction about the need for strong partnerships underpinned by the principles of subsidiarity and complementarity was reinforced.

- Subsidiarity in this context is understood as the delegation of responsibility based on the competencies, flexibility and capacities of the actors involved, whilst complementarity is the pooling of political and material resources for the accomplishment of a given objective.

- The R-ARCSS was signed on 12 September 2018 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, paving the way for the establishment of a Transitional Government of National Unity (TGONU). After several missed deadlines, the TGONU was finally inaugurated on 22 February 2020. The AU and UN played critical backstopping and other support roles to IGAD. For its part, the AU, through the Peace and Security Council, provided the necessary political cover for IGAD, whilst the UN kept the peace in South Sudan through its peacekeeping mission, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS). An online version of the R-ARCSS is available at: <https://www.dropbox.com/s/6dn3477q3f5472d/R-ARCSS.2018-i.pdf?dl=0>

- See: 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration Adopted by the 21st Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the African Union, 26 May 2013. Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36205-doc-50th_anniversary_solemn_declaration_en.pdf> [Accessed 18 March 2020]

- See: African Union (2016) Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by 2020. Lusaka, Zambia, 9 November. Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/38304-doc-1_au_roadmap_silencing_guns_2020_pdf_en.pdf> See also: Decision of the Assembly/AU/Dec.630 (XXVIII), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on 30–31 January 2017. Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/32520-sc19553_e_original_-_assembly_decisions_621-641_-_xxviii.pdf> [Accessed 06 March 2020]

- See: Charter of the United Nations, 1945. Available at: <https://www.un.org/en/charter-united-nations/> [Accessed 19 March 2020]

- See: Constitutive Act of the African Union, 2002. Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/34873-file-constitutiveact_en.pdf> [Accessed 18 March 2020]

- See: Charter of the United Nations, 1945. Op. Cit.

- The failure of the UNSC to agree on a statement on COVID-19 and the Secretary-General’s call for a global ceasefire, even when New York, the seat of the UN Headquarters, became the epicentre of the pandemic was a graphic illustration of the crippling dynamics that have come to characterise the Council.

- See: Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Partnership between the African Union and the United Nations on Peace and Security: Towards Greater Strategic and Political Convergence in January 2012. Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-rpt-au-un-partnership-ny-23-09-2013.pdf>; Report of the Secretary-General of the United Nations: Strengthening the Partnership Between the United Nations and the African Union on Issues of Peace and Security in Africa, including the work of the United Nations Office to the African Union, 2016. Available at: <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1302475?ln=en>. The Joint Framework Agreement was signed by the Chairperson of the AU Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat, and the Secretary General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, on 19 April 2017. [Accessed 29 March 2020]

- See: Decision Ext/Assembly/AU/Dec.1(XI), November 2018. Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/36425-ext_assembly_dec._1-4xi_e.pdf> [Accessed

24 March 2020] - Niamey Declaration of the First Mid-Year Coordination Meeting between the AU and Regional Economic Communities (RECs) on the Pursuit of the African Integration Agenda, MYCM/Decl.1(I), 8 July 2019. Available at: <https://www.tralac.org/documents/resources/african-union/2968-first-mid-year-coordination-meeting-between-the-au-recs-and-the-regional-mechanisms-declaration-july-2019/file.html> [Accessed

24 March 2020] - The strategy was adopted by the Council of Ministers of the LCBC in August 2018 and was endorsed by the AU PSC in December 2018. The strategy was developed with the support of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the German government through GiZ and the United Nations Office to the African Union (UNAOU).