This is one of the primary challenges that South Africa inherited this year when the country assumed the chairship of the AU – whose theme, rightly so, is focused on this elusive goal of silencing the guns. The questions are not how we got here – because we know the causes of our conflicts – but rather, what are the lessons to learn? Why is it so difficult to silence the guns?

First, with the advantage of hindsight, the 2020 deadline was clearly ambitious, mainly because it was not based on evidence or scientifically determined. Rather, it was largely declaratory and political, made in the heat of the moment during the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU)/AU in 2013. However, the rationale remains correct to this day, as the heads of state and government pledged in The 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration “not to bequeath the burden of conflicts to the next generation of Africans and undertake to end all wars in Africa by 2020”.1 Therefore, moving forward from 2020 and beyond, whatever future target we set for this noble goal should be informed by a scientific reading of the reality on the ground. It must be realistic and achievable, lest we demoralise ourselves and think we are failing when, in fact, the problem is in our methodology and long-term perspective.

Second, we have not given adequate attention to the root causes of our conflicts, although this was the intention in the Solemn Declaration. Among the envisaged actions towards 2020, the Solemn Declaration stated that we should “address the root causes of conflicts including economic and social disparities… Eradicate recurrent and address emerging sources of conflict” and “push forward the agenda of conflict prevention”.2 Among other things, it goes without saying that efforts to silence the guns should go beyond the slogan and create opportunities to boost the capacity of African institutions considerably to pre-empt conflicts in a more comprehensive and timely manner, rather than in a reactive conflict resolution approach. These efforts must also strengthen the continental conflict prevention ecosystem and increase our collective capacities to warn early and listen early, too.

Even though the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) is as close as ever to reaching its full operationalisation phase, evidence continues to show that Africa’s conflict resolution activities have tended to concentrate primarily on mediation, peace support operations (PSOs) and interventions. The deployment of PSOs in countries where conflict is ongoing is an indication of the challenges faced by actors to listen early and engage timeously, or at all. While the work of the PSOs can make significant impact on the ground – for instance, such as paving the way for elections – the reality is that such missions are too costly, too time consuming and take too long to produce results. PSOs do not necessarily provide a lasting solution to conflicts, given the multiplicity and complexity of the issues and actors involved in the conflict, but rather serve to de-escalate the conflict. In addition, the unpredictability of funding available for such operations threatens their existence, which is often shrouded in uncertainty.

In recent years, we have seen conflicts within the continent arising from factors that relate to structural vulnerabilities, such as competition over access to, use and illegal extraction of natural resources; social unrest resulting from poor and unaccountable governance; the prevalence of illicit small arms and light weapons; religious radicalisation; electoral disputes and more. These factors test the existing capacities to effectively prevent the impact of conflicts on national cohesion, rule of law, justice, and peace and security at large, among other things. The customary peacemaking approach of the APSA, therefore, must adapt and transcend the habitual data collection/analysis (Conflict Early Warning System/CEWS), mediation (the Panel of the Wise, the Pan-African Network of the Wise/PanWise, the Network of African Women in Conflict Prevention and Mediation/FemWise-Africa) and PSO interventions. The scope of the AU’s interventions should be broadened equally to include systematically structural conflict prevention that addresses the long-term root causes of potential violent conflict. Therefore, a two-pronged approach is needed, based on prevention and early action on the one hand and, on the other, the customary route of mediation and peacemaking. This will substantially lower the costs of intervention. The 2016 AU Master Roadmap of Practical Steps to Silence the Guns in Africa by Year 2020 (AUMR), developed by the Peace and Security Council (PSC), is anchored on this twin approach, but thus far, its implementation has been one-dimensional. The launch of the AU’s 2015 Continental Structural Conflict Prevention Framework (CSCPF)3 was a step in the right direction, even though countries are adhering to it very timidly.

Accordingly, the AU’s decision to position the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) as a tool for conflict prevention is a great opportunity to fill these gaps. The APRM’s mandate allows it to contribute to silencing the guns in Africa as it works to promote the AU’s ideals and shared values of democratic governance and inclusive development. It does this by encouraging all member states to collaborate and voluntarily participate in the home-grown, credible, rigorous, independent and self-driven peer review process and the implementation of its recommendations. The primary purpose of the APRM, therefore, is to foster the adoption of policies, standards and practices that lead to political stability, high economic growth, sustainable development and accelerated sub-regional and continental economic integration through the sharing of experiences and reinforcement of successful and best practice.

The APRM’s 22 country review reports are known for having pointed systematically at the fragilities of member states with great accuracy. As more of the APRM member states undergo the country review process, this will generate an incomparable repository of data to expand the capacity of Africa to rely on home-grown knowledge that is critical to crafting African solutions to African problems more resolutely. Furthermore, the APRM country evaluations have demonstrated that successful structural prevention should take into consideration deeper societal conditions. APRM indicators are beginning to point out that the next generation of conflicts is set to be related to governance, and will include aspects such as political succession to the country’s high office; the terms of office of incumbents; the peaceful transfer of power to an opponent after an election; disputes within political parties that spill over into broader society; the quantity, quality and outcome of elections; and inclusion, participation and diversity management vis-à-vis access to the state.

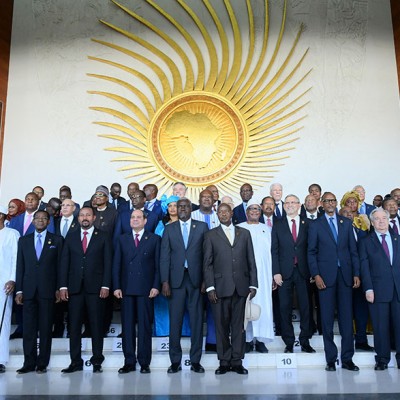

In terms of the work done by the APRM thus far, it is encouraging that its current membership has reached 40 countries as of February 2020. Among the latest countries to have joined the APRM during the recently concluded APR Forum of Heads of States, in February 2020, are Seychelles and Zimbabwe. The APRM is actively working towards reaching universal accession by 2023, which is a very realistic target, given the positive feedback already received from the remaining 15 countries. Equally encouraging is the growing confidence displayed by member states towards the peer review process itself, which continues to increase both quantitatively and qualitatively. For instance, in 2019 alone, the APRM conducted the following reviews: Egypt, which underwent its second-generation review; four targeted reviews undertaken for Djibouti (on fiscal decentralisation); Namibia (on youth unemployment); and two reports on Zambia (one on the contribution of mineral resources to the national economy, and a second on the contribution of tourism to the national economy). Lastly, several reviews are in the pipeline for 2020, including in Liberia, Niger, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda.

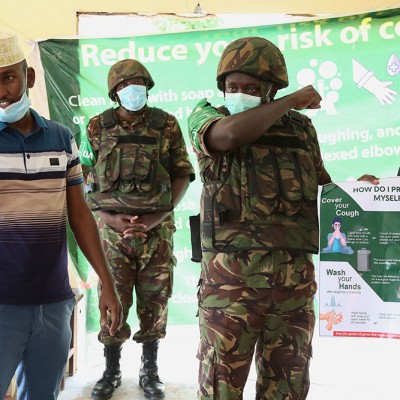

Furthermore, efforts to silence the guns in Africa will be significantly enhanced through greater collaboration across the various early warning systems and frameworks in Africa. For its part, the APRM launched a workshop series under the theme of “Silencing the guns and positioning the APRM as an early warning tool for conflict prevention”. The first workshop was held in February 2020 in Abuja, Nigeria, in collaboration with the Economic Commission for West African States (ECOWAS), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Savannah Centre for Diplomacy, Democracy and Development (SCDDD),

and specifically discussed linking the APRM country reports to early warning systems and conflict prevention. This resulted in the elaboration of the APRM Framework on Early Warning and Conflict Prevention, which outlines the existing gaps in the various early warning systems throughout Africa and the opportunities for collaboration between actors and mechanisms working specifically in the area of early warning, and identifies a niche and a role for the APRM, and local-based conflict prevention structures for a sustainable conflict prevention environment. This effort added to the growing collaboration between the PSC and the APRM, confirmed through the Communiqué of the 914th Meeting of the PSC, held on 5 March 2020. Among others, this underscored the need to synergise efforts and share experiences emanating from the APRM review processes to enhance efforts towards preventive diplomacy in Africa.4

In conclusion, our dependent model for eradicating conflicts in Africa is clearly not sustainable. The operationalisation of the AU’s Peace Fund is an important achievement in this regard, but more must still be done to capitalise it from Africa’s own resources. Peacemaking and peacekeeping are not cheap enterprises, and Africa must redouble its efforts to raise its own resources. We cannot muster and effectively manage the geopolitical interests of non-African actors involved in conflicts on our continent if we are in the game empty-handed. If we want to continue to find African solutions to African problems, we must do more to find and deploy African resources.

Professor Eddy Maloka is Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM). He writes in his personal capacity.

Endnotes

- See: African Union (2013) ‘The 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration’, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36205-doc-50th_anniversary_solemn_declaration_en.pdf> [Accessed 27 February 2020].

- Ibid.

- See: African Union (n.d.) ‘Continental Structural Conflict Prevention Framework: Country Structural Vulnerability and Resilience Assessments (CSVRAs), and Country Structural Vulnerability Mitigation Strategies (CSVMS)’, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/01-cscpf-booklet-updated-final.pdf> [Accessed 27 February 2020].

- See: African Union Peace and Security Council (n.d.) ‘Communiqué of the 914th Meeting of the PSC, 5 March 2020, on the Reports by the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) as Well as the Steps Taken to Position the APRM as an Early Warning Tool for Conflict Prevention’, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/en/article/communique-of-the-914th-meeting-of-the-psc-5-march-2020-on-the-reports-by-the-peer-review-mechanism-apmr-as-well-as-the-steps-taken-to-position-the-aprm-as-an-early-warning-tool-for-conflict-prevention>. [Accessed 6 March 2020].