Introduction

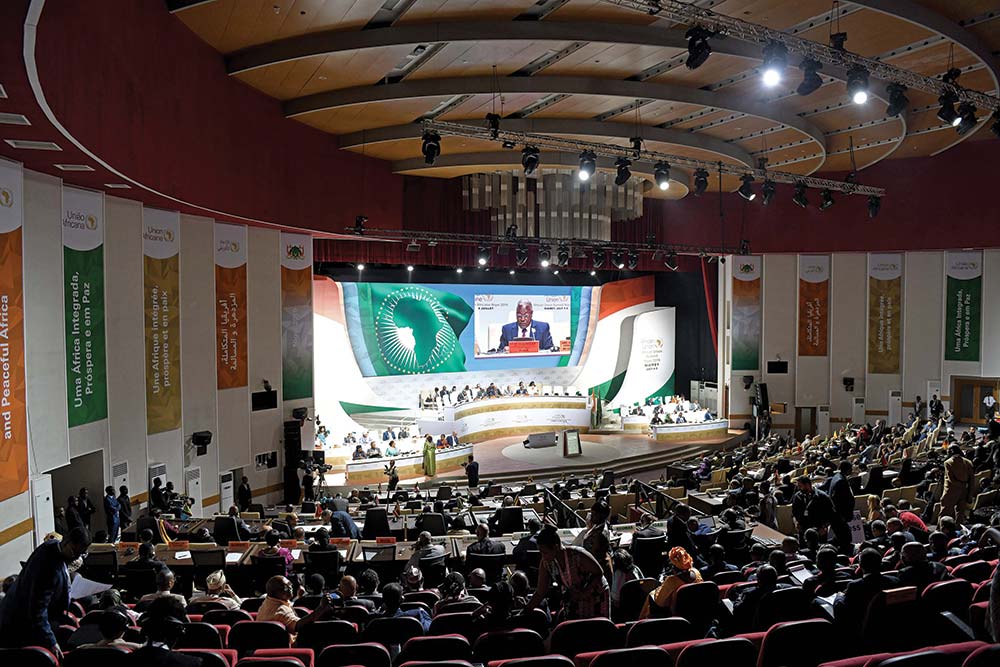

At the African Union’s (AU) 18th Ordinary Session in January 2012, held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, the heads of state and government of African countries agreed to establish the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).1 This free trade area is outlined in the African Continental Free Trade Agreement among 54 of the 55 AU member states currently. The AfCFTA is the largest in the world in terms of participating countries since the formation of the World Trade Organization,2 as it translates to a market potential for goods and services of 1.2 billion people, and an aggregate gross domestic product of about US$2.5 trillion.3

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) estimates that the agreement will boost intra-African trade by 52% by 2022.4 The AfCFTA treaty, one of the flagship projects of the AU Agenda 2063 and a landmark continental agreement, is aimed at creating a single continental market for goods and services, with free movement of businesspeople and investment. The agreement was brokered by the AU and was signed by 44 of its 55 member states in Kigali, Rwanda on 21 March 2018.5 The agreement went into force on 30 May 2019 and entered its operational phase following the AU Summit on 7 July 2019.6 This article examines the key provisions of the AfCFTA with the aim of identifying its prospects, and the challenges that may impede the exploitation of its full potential.

Literature Review

There is a significant body of literature on continental free trade agreements and socio-economic growth. Hosny contends that regional integration is characterised by improved competition, investment flows, economies of scale, technology transfer and improved productivity.7 Marinov argues that the effects of regional economic integration include increased investment, expenditure, sustainably increased demands, the consolidation of production and increased specialisation, improvement of the organisation and management of production and production technology, rationalisation of territorial distribution and utilisation of resources, increased production efficiency, and the enhancement of economic growth.8 Wandrei opines that trade agreements eventually lead to trade gains for participating countries.9

Examining the implications of the AfCFTA for individual states, Jibrilla argues that Nigeria’s earlier refusal to sign the AfCFTA was misguided. He contends that Nigeria stands to benefit the most from the agreement if the country improves its infrastructure, develops human capital, empowers youth and women, develops the agricultural sector, attracts quality foreign direct investment, encourages value addition, designs and implements policies that will allow access to finance by investors, and manages the security situation better.10 However, Ubi supports Nigeria’s initial refusal to sign the agreement, arguing that the AfCFTA was likely to undermine local manufacturers and entrepreneurs or lead to Nigeria becoming a dumping ground for finished goods. Ubi further argues that Africa’s development cannot be attained by free trade agreements, because past and current trade agreements involving African nations, particularly Nigeria, have not had any significant impact on the Nigerian economy.11 He further claims that most African countries are not mature enough for free trade, because of the lack of industrialisation. Ubi also states that the manufacturing sector in sub-Saharan Africa has not shown any growth since the 1970s, as the value-added goods percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) has stagnated at 10%.12

This article is therefore an examination of the prospects and challenges of the AfCFTA in the light of these debates. Drawing data from the AfCFTA, African Export–Import Bank (Afreximbank) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the article argues that a commitment to the principles of the AfCFTA, in the light of the signing of the agreement by Africa’s largest economies, indeed increases the prospect of the agreement becoming a reality that could improve industrialisation on the African continent and the welfare of the African people.

Overview of the AfCFTA

The AfCFTA provides a framework that covers trade liberalisation in goods and services in Africa. It is a product of negotiations of the Tripartite Free Trade Area (TFTA) – comprising the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the East African Community (EAC). Conversely, trade and market integration are at the heart of the Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) aims and objectives. For instance, ECOWAS’s Revised Treaty (Article 3) specifies the removal of trade barriers and harmonisation of trade policies for the establishment of a free trade area, a customs union, a common market and the eventual culmination in a monetary and economic union in West Africa.

In concordance with regional aspirations, Article 3 of the AfCFTA13 identifies the general objectives of the agreement to:

- create a single market for goods and services, facilitated by the movement of people to deepen the economic integration of the African continent, and in accordance with the pan-African vision of “an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa” enshrined in Agenda 2063;

- create a liberalised market for goods and services through successive rounds of negotiations;

- contribute to the movement of capital and natural people and facilitate investments building on the initiatives and developments in the state parties and regional economic communities (RECs);

- lay the foundation for the establishment of a continental customs union at a later stage;

- promote and attain sustainable and inclusive socio-economic development, gender equality and structural transformation of the state parties;

- enhance the competitiveness of the economies of state parties within the continent and the global market;

- promote industrial development through diversification and regional value chains in agriculture and food security; and

- resolve the challenges of multiple and overlapping memberships, and expedite the regional and continental integration processes.

To achieve these eight objectives, Article 4 of the AfCFTA14 contains the following seven specific further objectives:

- progressively eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods;

- progressively liberalise trade in services;

- cooperate on investment, intellectual property rights and competition policy;

- cooperate on all trade-related areas;

- cooperate on customs matters and the implementation of trade facilitation measures;

- establish a mechanism for the settlement of disputes concerning their rights and obligations; and

- establish and maintain an institutional framework for the implementation and administration of the AfCFTA.

Furthermore, to guide the process of achieving these objectives, the AfCFTA identifies principles that should guide members’ actions:

- driven by AU member states;

- RECs’ free trade areas (FTAs) as building blocks for the AfCFTA;

- variable geometry;15

- flexibility and special and differential treatment;16

- transparency and disclosure of information;

- preservation of the acquis;

- most-favoured nation (MFN) treatment;17

- national treatment;18

- reciprocity;

- substantial liberalisation;

- consensus in decision-making; and

- best practices in the RECs, the state parties and international conventions binding the AU.

Article 5 lists the institutional framework for the implementation, administration, facilitation, monitoring and evaluation of the AfCFTA as follows:

- the Assembly;

- the Council of Ministers;

- the Committee of Senior Trade Officials; and

- the Secretariat.

In terms of operationalisation, the implementation of the AfCFTA is being done in two phases. The first phase provides a framework for the liberalisation of trade in goods and services, and a mechanism for dispute settlement.19 For trade in goods, the agreement sets the path for eliminating tariffs on 90% of product categories. Countries can implement tariff reductions over a longer period in the case of sensitive goods, or maintain existing tariffs – where the products are excluded – for the remaining 10% of product categories. The protocol on trade in goods includes annexes on tariff concessions, rules of origin, customs cooperation, trade facilitation, non-tariff barriers, technical barriers to trade, sanitary and phyto-sanitary measures, and transit and trade remedies.20 Annex 4 to the agreement provides institutional structures for the progressive elimination of non-trade barriers (NTBs), a general categorisation of NTBs, reporting and monitoring tools, and facilitation of resolution of identified NTBs.

On the liberalisation of trade in services, member countries have also agreed to a request-and-offer approach, based on seven identified priority sectors: logistics and transport, financial services, tourism, professional services, energy services, construction, and communications. Phase I of the AfCFTA came into effect on 30 May 2019, 30 days after the 22nd ratification instrument was given to the chairman of the AU Commission.21

Phase II of the AfCFTA will cover competition policy, investment and intellectual property rights. Phase II pre-negotiation activities began in November 2018 with a meeting of experts (with the AU and UNECA) to discuss the issues of Phase II negotiations. This will be followed by a validation workshop, scheduled for 16-19 November 2019.22 The workshop will review the draft chapters of UNECA report, which forms the intellectual foundation of the Phase II negotiation that commences in February 2020.

The AfCFTA garnered added momentum at the AU’s 12th Extraordinary Session of the Assembly on 7 July 2019, when the operational phase of the AfCFTA was launched and Nigeria signed the AfCFTA alongside its neighbour, the Republic of Benin, leaving Eritrea as the only country yet to accede to the agreement. With a GDP of US$376.284 billion, Nigeria is considered the largest economy in Africa. It is followed by South Africa (US$349.299 billion) and Egypt (US$237.037 billion).23 With a population of about 200 million, Nigeria is also Africa’s largest market. Nigeria’s accession to the treaty is therefore seen as a major boost to the AfCFTA’s viability.

Prospects and Challenges of the AfCFTA

Although the AfCFTA signals a renewal towards a more integrated Africa in a bid to ease movement and trade, it will undoubtedly contribute to reinforcing African unity and advance “African solutions to African problems”. However, many analysts argue that the AfCFTA calls for cautious celebration and optimism. Currently, intra-African trade only constitutes 15% of overall African external trade. It is envisaged that with the elimination of tariffs, intraregional trade could increase approximately 15–20% in the medium term.24 This is ideally attainable since countries are expected to eliminate tariffs on 90% of products under the AfCFTA, leaving open the possibility of applying the reduction to either tariff lines or import values. Nevertheless, targeting tariff lines could yield tariff reductions as low as 15% only in terms of import values.25

The AfCFTA’s strong political backing from African heads of state has garnered traction at member state level, particularly around the projections of intra-African trade gains. The enthusiasm further stems from the fact that the AfCFTA comes on the heels of other continental efforts championed by the AU Commission. Notably, the AU launched a single air transport market during the 30th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the AU on 28 January 2018 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to boost connectivity and cut travel costs across the continent.26 Recognising that freer intra-Africa movement is not dependent on cheaper flights alone, it also launched an AU passport, which could potentially resolve glitches of intra-African mobility of goods and people. The AU passport, no doubt, will eliminate restrictions on inter-regional travel, particularly among countries that still require visas for entry. For example, Africa’s large economies, such as Nigeria and South Africa, still maintain entry by visa.

On the other hand, the range of outcomes from Africa’s RECs suggests that regional integration is a complex process with several factors at play beyond tariffs. Some of the concerns, such as accessibility to solid infrastructure (power, roads, rail, viable national private sector and local industries), would require a longer-term commitment to attain a conducive environment for robust continental trade. Infrastructure bottlenecks have been a great hindrance to the progress of intra-African trade. African economic integration requires up-to-date technology, and the application and dissemination of knowledge to facilitate rapid trade. For instance, already-existing trade areas such as ECOWAS, EAC and COMESA are grappling with the realities of weak infrastructure in their efforts to implement their regional free trade architecture. Perhaps the low level of critical infrastructure should be addressed before dedicating too much attention to more ambitious continental initiatives, especially as the regional challenges may be the same as those that would impede the AfCFTA initiative.

It is critical to interrogate the reasons behind the reality that Africa has only achieved 15% of intraregional trade and 3% of global trade.27 Even that performance percentage is driven by just four countries: South Africa, Namibia, Zambia and Nigeria – in that order – which does not compare favourably with intracontinental trade in the European Union (EU) (67%), Asia (58%), North America (48%) and even Latin America (20%).28

Nevertheless, beyond the challenges of the infrastructure deficit, poor access to finance, political uncertainty, inter-regional restriction on free movement and the demand for Western goods by some African consumers, some reports indicate that the AfCFTA offers significant prospects for African countries, as it could result in stronger integration among countries.29 From an economic perspective, the application of the principle of subsidiarity requires that the scope of the established regional institutions should match the region benefiting from the spillover. There is the possibility of the creation of a bigger and integrated regional market for African products. Furthermore, producers could equally have the opportunity to benefit from economies of scale and to access cheaper raw materials and intermediate inputs. The African market will not only have improved conditions for forming regional value chains, but will also be able to integrate to global value chains. However, much of the national economies in Africa are dominated by limited industrialisation and a primary production level, which is characterised by the mere extraction of raw materials and the lack of a large industrial sector. There is also the question of how bigger economies such as Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt and Kenya benefit from the arrangement, and how other countries are protected from the more diversified economies.

Conclusion

Beyond the commitment and political determination displayed by African heads of state, the larger operationalisation challenge of the AfCFTA lies in the ownership and participation of the African population. Critical buy-in that will birth local ownership and sustainability depends on the active involvement of the private sector, banking and local manufacturing sectors, small and medium cross-border traders, academia, civil society groups, organised women’s groups, cooperative societies and the media, in and across countries.

It is important to expand inclusiveness in the operation of the AfCFTA, especially in commencing early engagement with key national stakeholders. This should facilitate linkage between the RECs and also effectually communicate the benefits of the “celebrated continental arrangement”. It is useful to note that among other things, the 12th Assembly Decisions and Declaration of 7 July 2019 urged the UNECA, African Development Bank, Afreximbank and other key stakeholders, including development partners, to provide support for the establishment of the Secretariat of the AfCFTA in Accra, Ghana.

Expectations abound about the progress that will be reported at the January 2020 AU Summit on the AfCFTA. There is concurrence that this agreement may be the starting point of a long and complex journey towards the full realisation of the dream of a functional AfCFTA. The momentum galvanised at the launch of the operational phase of the AfCFTA on 7 July 2019, at the 12th Extraordinary Session of the AU Assembly, should be sustained by following through on the phases of implementation, as well as respect for the principles and decisions of the African heads of states and authorities.

Endnotes

- Saygili, Mesut; Peters, Ralf and Knebel, Christian (2018) African Continental Free Trade Area: Challenges and Opportunities of Tariff Reductions. Geneva: UNCTAD Research Paper, No. 15, p. 3.

- Crabtree, Justina (2018) ‘Africa is on the Verge of Forming the Largest Free Trade Area Since the World Trade Organization’, Available at: <https://www.cnbc.com/2018/03/20/africa-leaders-to-form-largest-free-trade-area-since-the-wto.html> [Accessed 3 August 2019].

- Moremong, Tshepidi (2019) The AFCFTA is a Giant Step Forward. The African Report, July-August, p. 8.

- Witschge, Loes (2018) ‘African Continental Free Trade Area: What You Need to Know’, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/03/african-continental-free-trade-area-afcfta-180317191954318.html> [Accessed 3 August 2019].

- No author (2018) ‘Forty-four African Countries Sign a Free-trade Deal’, The Economist, 22 March, Available at: <https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2018/03/22/forty-four-african-countries-sign-a-free-trade-deal> [Accessed 29 July 2019].

- African Union (AU) (2019) ‘AfCFTA Agreement Secures Minimum Threshold of 22 Ratification as Sierra Leone and the Saharawi Republic Deposit Instruments’, Available at: <https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20190429/afcfta-agreement-secures-minimum-threshold-22-ratification-sierra-leone-and> [Accessed 3 August 2019].

- Hosny, Amr (2013) Theories of Economic Integration: A Survey of the Economic and Political Literature. International Journal of Economy, Management and Social Sciences, 2 (5), pp. 133–155.

- Marinov, Eduard (2014) Economic Integration Theories and the Developing Countries. In Dautov, Rustem; Gkasis, Pavlos; Karamanos, Anastasios; Lagkas, Thomas; Prodromidou, Alexandra and Ypsilanti, Antonia (eds) Infusing Research and Knowledge in South-east Europe. Thessaloniki: South-East European Research Centre, pp. 164–177.

- Wandrei, Kevin (2018) ‘Advantages and Disadvantages of Regional Integration’, Available at: <https://classroom.synonym.com/advantagesdisadvantages-of-regional-integration-12083667.html> [Accessed 18 July 2019].

- Jibrilla, Adamu (2018) African Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) and its Implications for Nigeria: A Policy Perspective. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 2 (12), pp. 164–174.

- Ubi, Efem (2018) ‘Nigeria’s Abstention from the CFTA Agreement was No Mistake’, Available at: <http://www.financialnigeria.com/nigeria-sabstention-from-the- cfta-agreement-was- no-mistake-blog347.htm> [Accessed 18 July 2019].

- Ibid.

- AU (2019) ‘“Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area’,”. Available at: <https://au.int/en/treaties/agreement-establishing-african-continental-free-trade-area> [Accessed 19 July 2019].

- Ibid.

- Variable geometry is a strategic principle used in international trade negotiation that involves many countries and issues. Negotiations of some of the issues may not be binding on all parties to the agreement. It provides an alternative to agreements with provisions that are binding on all parties. It is an opt-in agreement devised by a subset of a large group of countries with benefits restricted to the subset countries.

- Article 6 of the AfCFTA provides that state parties shall provide flexibilities to other state parties at different levels of economic development. These flexibilities shall include special consideration and additional transition periods in the implementation of the agreement.

- This refers to the liberty that state parties have to conclude or maintain a preferential trade arrangement with other state parties and third parties, insofar as such an arrangement does not frustrate or impede the objectives of the AfCFTA.

- This refers to a state party according equal treatment to products imported from other state parties after customs clearance.

- Abrego, Lisandro; Amado, Maria; Gursoy, Tunc; Nicholls, Garth and Perez-Saiz, Hector (2019) The African Continental Free Trade Agreement: Welfare Gain Estimates from a General Equilibrium Model. Washington, DC: IMF, p. 5.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) (2019) ‘Experts Meet to Set the Stage for AfCFTA Phase II Negotiations’, Available at: <https://www.uneca.org/stories/experts-meet-set-stage-afcfta-phase-ii-negotiations> [Accessed 31 August 2019].

- Oyekunle, Olumide (2019) The Largest Economies in Africa by GDP, 2019. The African Exponent, 20 February 2019.

- Moremong, Tshepidi (2019) op. cit., p. 8.

- UNECA (2018) African Continental Free Trade Area: Towards the Finalization of Modalities on Goods. Addis Ababa: Economic Commission for Africa, p. 10.

- AU (2018) ‘Assembly of the Union Thirtieth Ordinary Session: Decisions, Declarations and Resolution’, p. 1, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/decisions/33908-assembly_decisions_665_-_689_e.pdf> [Accessed 19 July 2019].

- African Export–Import Bank (Afreximbank) (2018) Africa Trade Report. Cairo: Afreximbank, p. 15.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (2019) ‘AfCFTA Thriving in a New Africa’, Available at: <www.pwc.com/ng> [Accessed 8 July 2019]; and UNECA (2019) The Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) in Africa – A Human Rights Perspective. Geneva: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Afreximbank (2018) op. cit., p. 15; PricewaterhouseCoopers (2019), op. cit.; and UNECA (2019) op. cit.