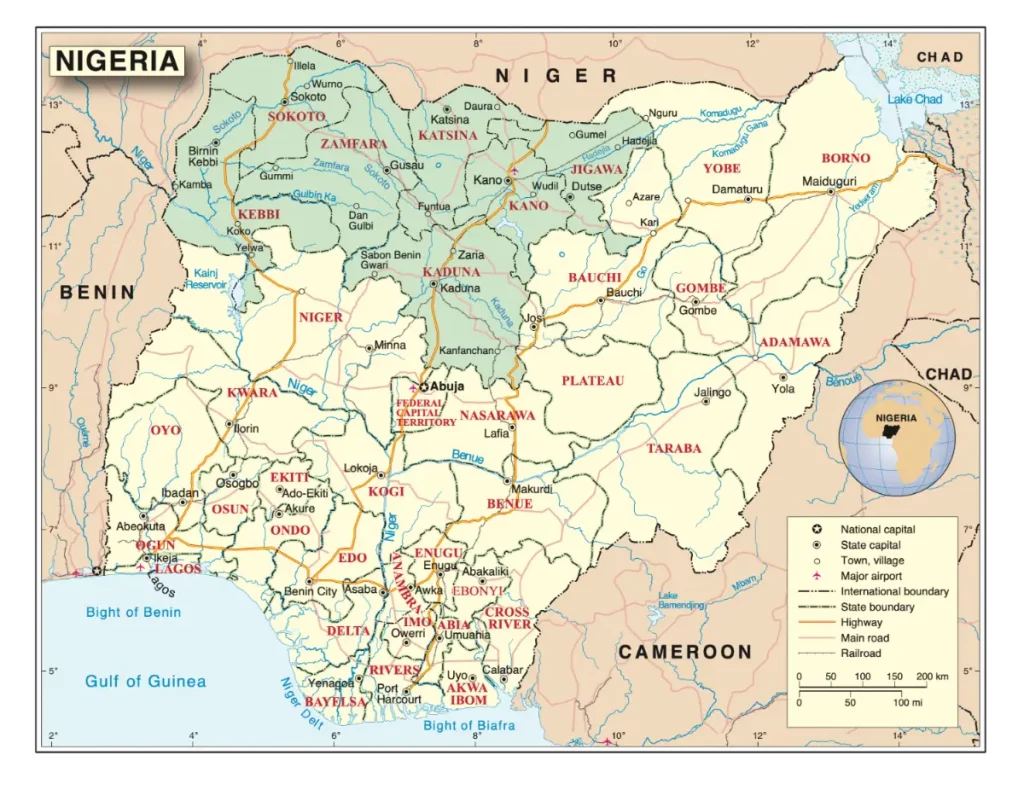

Armed banditry in Nigeria’s Northwest geopolitical zone is driving an unprecedented national humanitarian and security crisis in terms of its disruptive impact and human casualties,1Ojewale, O. (2024) ‘Learning on the edge: Impacts of banditry on education and strategic options for resilience in northwest Nigeria’, African Security Review, 33(2), 210–227, https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2024.2327314 with bandits responsible for more deaths than Boko Haram and other non-state armed groups combined.2Mac-Leva, F. and Ibrahim, H. (2019) ‘Bandits kill more Nigerians than Boko Haram, robbers, kidnappers, cultists, others’, Daily Trust, 22 September, Available at: https://dailytrust.com/bandits-kill-more-nigerians-than-boko-haram-robbers-kidnappers-cultists-others [Date accessed: October 14, 2024]. Bandits are the various organised criminal groups involved in rape and other sexual violence, kidnap-for-ransom, armed robbery, cattle rustling, pillage and attacks on traders, farmers, and travellers, particularly in Nigeria’s Northeast region.3Osasona, T. (2023) ‘The question of definition: Armed banditry in Nigeria’s North-West in the context of international humanitarian law’, International Review of the Red Cross, 105(923), 735–749, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383122000455 While banditry is rapidly extending into other Nigerian geopolitical zones, the Northwest is the epicentre of this emergency in Nigeria.

In a geopolitical zone blighted by poverty, this security crisis has worsened socioeconomic outcomes, as women and other vulnerable groups are disproportionately affected.4Amaefule, E. (2018) ‘Poverty more endemic in North-West Nigeria – Report’, The Punch, 22 October, Available at: https://punchng.com/poverty-more-endemic-in-north-west-nigeria-report [Date accessed: July 10, 2024]. There are 9% more women than men who are internally displaced persons in the region.5Onyenike, P. O. (2020) ‘Internal Displacement in North West & North Central Nigeria: What can we learn from the numbers?’ Towards Data Science, 8 January, Available at: https://towardsdatascience.com/internal-displacement-in-north-west-north-central-nigeria-b313c939b3b5 [Date accessed: January 8, 2020]. Utilisation of maternal healthcare is lower than the national average in the region.6Okoli, C.; Hajizadeh, M.; Rahman, M. M.; and Khanam, R. (2020) ‘Geographical and socioeconomic inequalities in the utilization of maternal healthcare services in Nigeria: 2003–2017’, BMC Health Services Research, 20, 849, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05700-w Only 29% of women in the region are literate. In addition, girls suffer more than boys in terms of missing out on education,7UNICEF (2022) ‘Situation of women and children in Nigeria: Challenges faced by women and children in Nigeria’, Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/situation-women-and-children-nigeria [Date accessed: July 20, 2024]. with around 47% of eligible girls in the region receiving primary education.8Sasu, D. D. (2022) ‘Literacy rate in Nigeria 2018, by zone and gender’, Statista, 1 February, Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1124745/literacy-rate-in-nigeria-by-zone-and-gender [Date accessed: February 1, 2022]. These poor socioeconomic outcomes are direct pointers to the failure of governance systems in the region.

While the literature on this crisis is thin, it is the preponderant opinion of scholars that economic incentives and personal enrichment drive banditry, rather than political, ideological, or any sectional interest.9Barnett, J.; Rufa’i, M. A.; and Abdulaziz, A. (2022) ‘Northwestern Nigeria: A Jihadization of Banditry, or a ‘Banditization’ of Jihad?’ CTC Sentinel, 15(1), 46, Available at: https://ctc.westpoint.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/CTC-SENTINEL-012022.pdf [Date accessed: August 15, 2024]; Ojewale, O. (2024) ‘Northwest Nigeria Has a Banditry Problem. What’s Driving It?’ The International Peace Institute Observatory, 22 May, Available at: https://theglobalobservatory.org/2024/05/northwest-nigeria-has-a-banditry-problem-whats-driving-it [Date accessed: May 22, 2024]; Osasona, T. (2023) ‘The question of definition’, op. cit. Bandits are indiscriminate in their attacks, and they have plundered communities of different faiths and ethnicities across the region with the same level of brutality. While people of Fulani ethnicity dominate these bandit groups, its victims have been crosscutting, irrespective of gender, religion, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.10Oyero, K. (2021) ‘Most bandits are Fulani who profess same religious beliefs as me –Masari’, The Punch, 6 September, Available at: https://punchng.com/most-bandits-are-fulani-who-profess-same-religious-beliefs-as-me-masari [Date accessed: September 6, 2024].

The victimisation of women in a context of conflict

Violence against women occurs in all contemporary armed conflicts. Although men are also victims of sustained aggression, there are critical differences between men’s and women’s experiences of violence in armed hostilities.11Bernard, V. and Durham, H. (2014) ‘Sexual violence in armed conflict: From breaking the silence to breaking the cycle’, International Review of the Red Cross, 96(894), 427–434, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383115000442 Apart from the fact that conflicts strengthen some of the existing social and cultural domination of the female gender and marginalise women, conflicts exacerbate women’s feelings of helplessness by affecting their physical and mental wellbeing.12Nikolić-Ristanović (2002) ‘War and Post-War Victimization of Women’, European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, 10(2), 138–145, https://doi.org/10.1163/157181702401475322

There have been significant scholarly attempts at defining and distinguishing wartime or conflict-related rape from the crime of rape as criminal assault. Gottschall, using the term interchangeably with mass wartime rape, refers to it as distinct patterns of rape by combatants at rates that are significantly increased over rates of rape during peacetime.13Gottschall, J. (2004) ‘Explaining Wartime Rape’, Journal of Sex Research, 41(2), 129–136. Furthermore, Cohen highlighted the features of wartime rape as frequent, occurring on a mass scale, systemic, prevalent, and for its use as a tool or tactic.14Cohen, D. (2013) ‘Explaining Rape during Civil War: Cross-National Evidence (1980–2009)’, American Political Science Review, 107(3), 462–477.

A scan through the literature on conflict-related rape shows that conceptual frameworks for explaining the phenomenon can include four clear categories, namely, explanatory frameworks with biosocial theoretical frameworks, theoretical frameworks that explain the phenomenon using the sociology of gender relations and culture, feminism-oriented theoretical frameworks, and strategic rape theory.15Gottschall, J. (2004) ‘Explaining Wartime Rape’, op. cit. With the exception of biosocial theories, there are several thematic concurrences among the other three theories regarding rape as a product of particular social and cultural contexts, with the divergence being the attribution of responsibility to specific sociocultural factors. Conversely, biosocial theories argue that the attribution of causation to sociocultural factors is insufficient, as the evolved sexual psychology of male soldiers driving sexual desires is a primary factor.16Thornhill, R. and Palmer, C. (2000) A Natural History of Rape, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Of all the four theoretical frames, the strategic rape theory is the most influential theory about mass rape in conflicts and the most referenced in literature by researchers, multilateral organisations and practitioners.17Gottschall, J. (2004) ‘Explaining Wartime Rape’, op. cit. The prominence of the theory is in large part due to its preference by feminist scholars and activists that established the nexus between the history of conflicts and systemic rape.18Kirby, P. (2012) ‘How is rape a weapon of war? Feminist international relations, modes of critical explanation and the study of wartime sexual violence’, European Journal of International Relations, 19(4), 799–823. Susan Brownmiller’s works are influential in structuring the outlay of the theory. Mass rapes in the Yugoslavian and Rwandan conflicts propelled the theory as a critical weapon as important as other implementations of warfare available to an army.19Brownmiller, S. (1993) Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, New York: Simon and Schuster, reprint. The argument of the proponents of the theory is not that routine military instructions always overtly demand soldiers to rape. However, the impact of mass rape is evident in its coherence and coordination as an effective war strategy.20Vikman, E. (2005) ‘Ancient origins: Sexual violence in warfare, part I’, Anthropology & Medicine, 12(1), 21–31.

The near-unanimous conclusion across the literature is that the pernicious aim of the strategic deployment of mass rape as a tactic of warfare is the infliction of devastatingly lasting harm on the targeted enemy population. Gottschall concretely paints a stark picture of the impact of wartime rape as follows:

It is credited with spreading debilitating terror, diminishing the resistance of civilians, and demoralising, humiliating, and emasculating enemy soldiers who are thereby shown to have failed in their most elemental protective duties. Further, mass rape is said to cast blight on the very roots of the afflicted culture, affecting its capacity to remain coherent and to reproduce itself. By raping women, soldiers split the familial atoms of which every society is composed.21Gottschall, J. (2004) ‘Explaining Wartime Rape’, op. cit., p. 131.

The three dimensions of criminal victimisation of women and girls in Nigeria’s Northwest

Women and girls across the region are directly affected by the indiscriminate sexual violence routinely used by bandits against rural communities. One of the dominant trends in almost all reported attacks by bandits on rural communities in the region is the repeated incidents of targeted abduction and rape of women and girls.22Yaba, M. (2021) ‘Kaduna: Bandits kill 222, rape 20 women in 3 months – Report’, Daily Trust, 13 July, Available at: https://dailytrust.com/kaduna-bandits-kill-222-rape-20-women-in-3-months-report [Date accessed: October 10, 2024]. Bandits attack, sometimes just to rape and abduct sexual slaves. According to a victim:

On that fateful day, they kidnapped 10 women, including those who had infants. […] I followed the other women into the forest and we were held for two days. […] They made sure all the women abducted were raped. So, we all watched as they raped every one of us in our presence. They were two men, each of them had their way with me twice. They had told us before we left the village that they came for the wives. They didn’t demand ransom; the abduction was only for sexual gratification.23Abdullahi, M. (2022) ‘Seized for pleasure: The tragic plight of girls, women abducted by bandits in Niger’, Development Cable, 26 July, Available at: https://www.thecable.ng/seized-for-pleasure-the-tragic-plight-of-girls-women-abducted-by-bandits-in-niger [Date accessed: July 26, 2024].

Another victim narrating her ordeal stated:

They came and asked me […] where is my husband and I told them that he has gone to the farm, and the next thing, two of them just dragged me inside and asked me to remove my cloth. […] I started begging them and one of them hit me with a gun and I fell down and he began to rape me, his second also did the same thing […] they told us that they would kill any woman who refused to obey them.24Adam, J. (2021) ‘Mass gang-rape of women, girls by bandits in Niger communities’, The Sun, 24 November, Available at: https://thesun.ng/mass-gang-rape-of-women-girls-by-bandits-in-niger-communities [Date accessed: October 10, 2024].

According to various reports by the police, arrested bandits across the region confessed to raping victims multiple times and across different locations, highlighting a pattern of targeting women and girls for sexual gratification.25Nathaniel, S. (2021) ‘I Raped Her Every Day For Five Months, Says Bandit Who Kidnapped Housewife’, Channels TV, 27 June, Available at: https://www.channelstv.com/2021/06/27/i-raped-her-every-day-for-five-months-says-bandit-who-kidnapped-housewife [Date accessed: October 10, 2024]; Sahara Reporters (2022) ‘14-year-old Bandit Known For Raping Female Victims Arrested In Zamfara’, 10 February, Available at: https://saharareporters.com/2022/02/10/14-year-old-bandit-known-raping-female-victims-arrested-zamfara [Date accessed: October 10, 2024]. Secondly, bandits weaponise sexual violence against communities to exact compliance. In one community, bandits randomly raped women as punishment for not paying the levies imposed by the group.26Ogalah, D. (2021) ‘Bandits rape women, loot Zamfara community for not paying levy’, Daily Post, 15 November, Available at: https://dailypost.ng/2021/11/15/bandits-rape-women-loot-zamfara-community-for-not-paying-levy [Date accessed:August 10, 2024]. Another media report stated that no fewer than five communities in Zamfara state fled their homes after bandits resorted to raping women and children for not paying levies imposed on their respective communities.27Ahmed, A. (2022) ‘Bandits raping our wives, daughters for failing to pay N2m levy per community — Zamfara residents’, The Tribune, 22 January, Available at: https://tribuneonlineng.com/bandits-raping-our-wives-daughters-for-failing-to-pay-n2m-levy-per-community-zamfara-residents [Date accessed: January 22, 2022]. There is a pattern to this weaponisation of sexual violence as a tool of extortion by bandits, and the impact of this is grave on communities, putting into perspective the very strict social mores of these societies. Women who resist are killed or harmed, and in one particular instance, bandits prevented the burial of a victim who was killed for resisting rape by bandits.28Daily Trust (2021) ‘Bandits are raping us, Zamfara women speak’, Daily Trust, 29 December, Available at: https://dailytrust.com/bandits-are-raping-us-zamfara-women-speak [Date accessed: July 10, 2024]; Umar, S. (2014) ‘Bandits on killing, gang-raping spree in Zamfara’, Daily Trust, 13 September, Available at: https://dailytrust.com/bandits-on-killing-gang-raping-spree-in-zamfara [Date accessed: July 15, g 2024].

The third dimension of victimisation is the forced marriage of kidnapped girls in the region by bandits to some of the men within their ranks.29The Vanguard (2022) ‘Bandits threaten to marry off 21-year-old woman if N1.7m ransom is not paid in Niger’, 21 April, Available at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2022/04/bandits-threaten-to-marry-off-21-year-old-woman-if-n1-7m-ransom-is-not-paid-in-niger [Date accessed: April 21, 2022]. This is one area of similarity between bandits who operate in Nigeria’s Northwest and fundamentalist Islamist groups that are active in the Northeast geopolitical zone.

Does International Humanitarian Law offer any respite?

There is no hierarchy of prioritisation of conflicts in International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and for the principles of IHL International Armed Conflicts and Non-International Armed Conflicts alike.30Mack, M. and Pejic, J. (2008) ‘Increasing Respect for International Humanitarian Law in Non-international Armed Conflicts’, International Committee of the Red Cross, Available at: https://www.icrc.org/sites/default/files/topic/file_plus_list/0923-increasing_respect_for_international_humanitarian_law_in_non-international_armed_conflicts.pdf [Date accessed: July 15, 2024]. However, applicable IHL principles exclude ‘situations of internal disturbances and tensions, such as protests, isolated and sporadic acts of violence, and other acts of a similar nature.’31Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (1996) ‘Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II)’, Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-additional-geneva-conventions-12-august-1949-and [Date accessed: October 14, 2024]. Banditry has been stated as one of those acts of violence excluded from the operational regime of IHL.

In a landmark decision in the case of convicted war criminal Dusko Tadić, the Trial Chambers of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) established a crucial distinction between an armed conflict and activities such as banditry, unorganised and short-lived insurrections or terrorist acts.32Prosecutor v. Duko Tadić (1997) ICTY Trial Chambers, IT-94-1-T, 7 May, Available at: https://www.icty.org/x/cases/tadic/tjug/en/tad-tsj70507JT2-e.pdf [Date accessed: October 14, 2024]. This distinction aligns with the guidance provided in the Commentaries on the First and Fourth Geneva Conventions, which state that these criteria serve a vital purpose in differentiating a genuine armed conflict from mere criminal acts like banditry or fleeting, disorganised uprisings. Also, some IHL scholars have argued that banditry is excluded from the range of violent acts in the operation of international laws of conflict.33Cullen, A. (2010) The Concept of Non-International Armed Conflict in International Humanitarian Law, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

As it stands, IHL does not provide legal protection for victims of banditry in Nigeria. This is particularly concerning as banditry has become characteristic of contemporary armed conflict in Nigeria and the extended West African Sahel, highlighting the limitations of state authority in the region. The existing framework of IHL excludes the prosecution of humanitarian crimes committed by bandits. This raises significant questions about the effectiveness of IHL and even International Human Rights Law in addressing future conflicts within the Sahel. However, it is important to note that while IHL may not directly apply to banditry in Northwest Nigeria, the actions perpetrated by these groups can still constitute crimes against humanity. These crimes can be prosecuted under national law or by the International Criminal Court (ICC). However, the politics around the ICC on the continent limits the efficiency of this alternative.

Revictmisation of victims by communities

Beyond the trauma of physical violation by bandits, women and girls in the region suffer additional disadvantages as a result of various sociocultural practices. These cultural practices range from traditions that girls are not bearers of family names, unlike their male counterparts, and are therefore expected to marry young, to cultural and religious practices that demand chastity from women and have more pronounced roles in domestic life.34Kozieł, P. (2014) ‘Hausa women’s rights and changing perception of gender in Northern Nigeria’, In: Pawlak, N.; Will, I.; and Siwierska, E. (Eds), Hausa and Chadic studies in honour of Professor Stanisław Piłaszewicz, Warsaw: Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa, pp. 215–229. It is, therefore, not surprising that those victims are stigmatised in their respective communities. It has been suggested that some husbands are seeking divorce on the suspicion that bandits have violated their kidnapped wives.35Sani, S. (2022) X post, 10 February, Available at: https://x.com/ShehuSani/status/1491781188209582082 [Date accessed: February 10, 2022].

The ICC’s mandate to enforce and induce compliance with international law prohibiting impunity provides a window of opportunity for redress for victims of sexual violence by bandits in Nigeria. This prospect is bolstered by the failure of the Nigerian state to prosecute the largely known perpetrators of these crimes. Beyond failing in its constitutional obligations to protect citizens from sexual violence, the state has failed to prosecute offenders for rape and other sexual violence in spite of the existing comprehensive legal regime available to prosecute offenders under Nigerian legislation.36Oba, C. O. (2020) ‘Prosecuting Offenders for Rape Committed in Armed Conflict: Interrogating the Accountability of the Nigerian State’, Human Rights Brief, 23, 43–47. There is no record of prosecution of bandits for sexual violence in Nigeria, and according to the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) Country Representative in Nigeria, ‘It scares me that bandits are not taken to courts even though they have been assaulting and killing children and women; abducting and raping.’37Abubakar, U. (2023) ‘Prosecute bandits for killing children, women, UNICEF urges FG’, The Punch, 18 August, Available at: https://healthwise.punchng.com/strengthen-judiciary-prosecute-bandits-for-killing-children-women-unicef-urges-fg [Date accessed: July 10, 2024].

Grimly, victims of sexual violence in the Northwest are dehumanised and subjected to harrowing physical, mental and emotional suffering. The lack of respite for women, in terms of justice for them and proactivity by the state against the bandits, are the signs of not just victimisation but the erosion of dignity, personhood and womanhood.

Tosin Osasona is an international development professional with over a decade of experience in conflict analysis, public policy and governance research and program management. He is interested in policy-driven interventions and strategies aimed at enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of security and justice institutions in Nigeria and the West African Sahel.