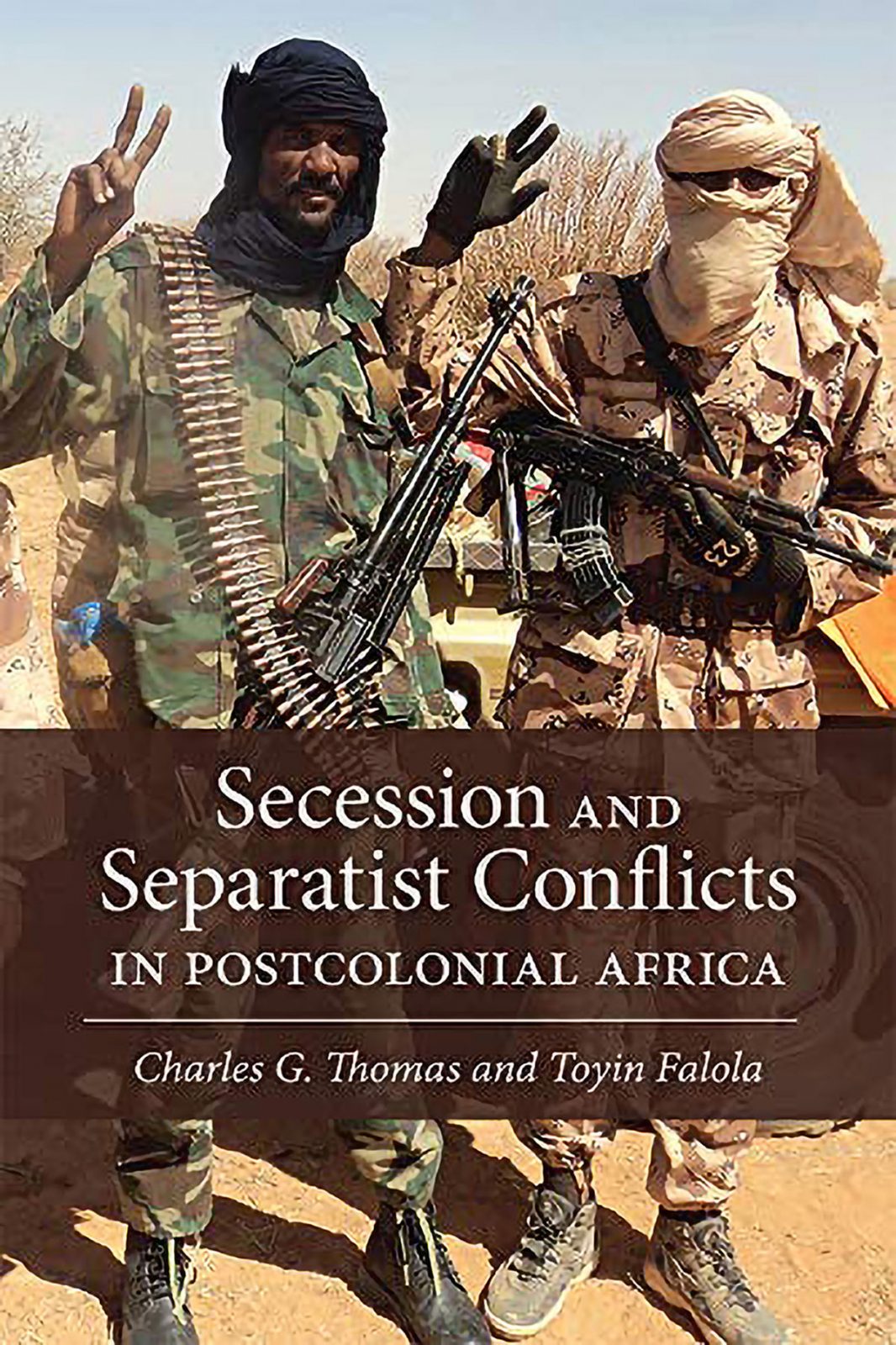

Since the end of the Katangese secessionist crisis in the Congo in the early 1960s, separatist and secessionist conflicts have attracted the attention of scholars and researchers across disciplinary boundaries. Perhaps the need to re-engage the historico-structural forces that had shaped the contours and trajectories of secessionist and separatist conflicts in Africa, coupled with the imperative of explaining the new wave of secessionist demands in recent times, led to the development of Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa. As the authors themselves state, the purpose is to “to explain the historical context and precedents that have shaped the concept and practice of secessionist conflicts in Africa from independence” (p. 1).

Authored by Charles G. Thomas and Toyin Falola, two foremost scholars of African studies, Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial African Politics, a 344-page book, is organised into six well-written chapters, inclusive of the introduction and the concluding sections. The book opens with an introductory section (pp. 1–22) in which the authors provide the reasons behind secessionist conflicts in post-colonial Africa. Specifically, the authors attempt to lay the conceptual and theoretical foundation for the case studies that are examined in the book. Most informative and novel is the attempt to clear the conceptual ambiguities by delineating the concepts of secessionist conflicts from two other forms of internal conflicts in Africa, namely liberation conflicts and reform conflicts. The authors contend that while liberation and reform conflicts in terms of objectives seek to seize the control of the state apparatus and thereby gain sovereignty for certain factions, secession conflicts aim at severing sovereignty completely.

In part one, comprising two chapters (pp. 23–98) with the theme “Civil Secessions”, the authors undertake an excursion into the historical forces that drove the quest for self-determination among African nations. To be sure, in the introductory opening to the two chapters, the authors seem to suggest that self-determination – the core argument that formed the basis for the decolonisation struggles and the eventual independence of many countries in Africa in the early 1960s – also underlines the quest for civil secessions. Following the introductory opening of part one is the exploration of the first case study: the Katangese civil secession. In this chapter, titled “The Secession of Katanga, 1960–1963”, the authors, drawing from the history of state formation in the Congo, explore the historico-social, economic, political and external forces that sustained the attempt by Katanga Province to secede from the rest of the Congo.

Specifically, the authors argue that what sustained the Tshombe-led secessionist violence against the Congolese state, beyond the political instability that heralded the country’s independence, was the lack of a clearly defined mandate by the United Nations at the beginning of the conflict, and also the imperialist support rendered to the Tshombe regime by Belgium. Beyond these factors, the authors submit that the Katangese secessionist conflict signalled to the world of the inherent weakness of post-colonial African states to deal with internal threats to their existence.

Issues similar to the Katangese secession were also explored in the second chapter of the book. With a focus on Biafra’s secessionist conflict in Nigeria between 1967 and 1970, the authors attempt to lay bare the context of the 30-month Biafran conflict, what sustained it and why it failed. Like the Katangese case, the authors argue that General Odumegwu Ojukwu’s desire to exit the Biafran State from Nigeria, through a violent route, was framed through the lens of self-determination in the colonial context. This reasoning, coupled with the belief that Biafra had oil that could sustain it as a nation-state, sustained the conflict. In the two chapters, the authors unpack that the Katangese and Biafran secessionist conflicts not only tested the viability of the African state system in the post-colonial era but also taught the leaders, through the auspices of the Organisation of African Unity, how to deal with secessionist demands.

The second part of the book, with the theme “The Long Wars”, is made up of two chapters (pp. 99–187). In these two chapters, the authors discuss how a novel strategy, different from that employed by the leaders of Biafra and Katanga, made the difference in making secession possible. In chapters three and four of the book, the authors, drawing from the examples of the Eritrean and South Sudanese separatist movements, demonstrate how the tactics and strategy of prolonged war, adopted by the leaders of the secessionist struggles against the Ethiopian and Sudanese states, sustained the conflicts for decades. The central argument that the authors make is that critical and crucial to the successes of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) and the Sudanese Peoples’ Liberation Army (SPLA) was the implementation of Maoist theory of protracted warfare, which is anchored on the strategy of prolonging a conflict for the purpose of disorientating the enemies. This factor, coupled with the secessionist groups’ strategy of winning the support of the locals during the conflicts with the extant states’ armies, accounted for the successes.

Part three, titled “The New Wave of Secessions”, includes chapters five and six (pp. 189–262). In the fifth chapter, the authors not only trace the trajectory of the crisis that led to the Somalian civil war but also unearth the forces that made the secession of Somaliland possible. What has sustained Somaliland as a de facto state is also explored. The authors framed the Somali civil war against the background of the failure of the central state to build a nation. It was such a failing that prompted the disintegration and exit of Somaliland. As the authors explain: “It was only the collapse of the rest of the state into a deadly civil war and its inability to effectively reintegrate that convinced the people of Somaliland that they not only could but should remain a separate political body” (p. 204). The book posits that Somaliland has sustained its de facto status in regional affairs because its unrecognised government has built para-diplomatic relationships with a few regional states.

In the sixth chapter, the book focuses on the Tauregs’ struggles for group recognition and explores the dynamics of secessionist conflicts in a transnational context. The main theme that seems to run through the entire chapter is that at the centre of the secessionist conflicts were the authorities in Bamako and Niamey, pitched against the Tuaregs in the quest for the state of Aswad. This is unconnected to the failure of the central states in Bamako and Niamey to include the Tuaregs in national affairs.

In the concluding part of the book (pp. 263–286), the authors echo the historical factors that have, over the years, shaped the trajectories and dimensions of secessionist struggles and conflicts in post-colonial Africa. Conclusively, the authors submit that there is increasing recourse to separatism rather than secession. This trend, according to the authors, is unconnected to current world dynamics, which are underpinned by a state-centric policy supported by a hegemonic United States of America pursuing a war on terror.

There is no doubt that Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa has not only contributed to the dearth of literature on secessionist and separatist conflicts in Africa, but has also enhanced our understanding of the subject. The book is therefore a worthy addition to the bourgeoning literature on self-determination conflicts in post-colonial Africa. Although many books have previously charted this course, as indicated earlier, what this book does, with sound histographical finesse, is to deepen the discourse on the subject. Drawing from historic and empirical studies, the book addresses in more detail the intersections of state, politics and ethno-national conflicts in Africa, within the context of international law and diplomacy.

Each of the chapters in the book capture the three waves of secessionist conflicts in post-colonial Africa, namely liberation, long wars and the new secessionist wave. A major challenge noticeable in the book is the authors’ failure to create an appendix presenting the list of abbreviations used, since many of such appear in the book. This notwithstanding, the book is an inspiring read and should be a valuable resource for members of the research community in Africa and beyond. It is strongly recommended for students of political science, international law, sociology and peace studies at both the undergraduate and graduate levels, as well as diplomats, media practitioners and the general public.

Adeniyi S. Basiru is an Independent Researcher, Policy Analyst and Doctoral Scholar at the University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria.