Introduction

This article evaluates the role of the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) in resolving electoral conflicts in Zimbabwe, emphasising the organisation’s constrained enforcement capacity and reliance on diplomatic strategies. The discussion delves into the SADC and African Union (AU) institutional structures and preparedness to manage such conflicts, assessing their effectiveness in promoting democratic governance standards within the region. The author contends that, despite articulating governance norms, SADC’s intervention efforts are hindered by enforcement limitations and solidarity rooted in liberation movements, necessitating a reliance on moral persuasion and diplomatic tactics. The consequence is the violation of the SADC guidelines1SADC (2015) ‘SADC Principles and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections’, Available at: <https://www.sadc.int/file/6076/download?token=lztE9Vx7> [Accessed on October 2023]. and principles governing democratic elections.

Since 1985, Zimbabwe has faced election-related conflicts, with an escalating trend since the 2000s. The AU and SADC, as continental brokers, often intervene belatedly, lacking coercive authority. SADC’s coercive authority involves sanctions and military intervention, contingent on Member States’ consensus and collective commitment. Despite normative frameworks, there are allegations of rigging in Zimbabwe’s elections. The crucial question is whether SADC can effectively prevent civilian deaths in the electoral process, given that in the 2018 and 2023 disputes, the Responsibility to Protect was solely entrusted to the state. The article concludes by emphasising the significance of interpreting election-related conflict violations for adequate SADC attention and intervention. The historical lack of SADC intervention in violent election incidents across SADC countries has contributed to large-scale violence in subsequent instances, exemplified by Zimbabwe’s 2018 and 2023 elections.

Towards a conceptual framework: Electoral-related conflict

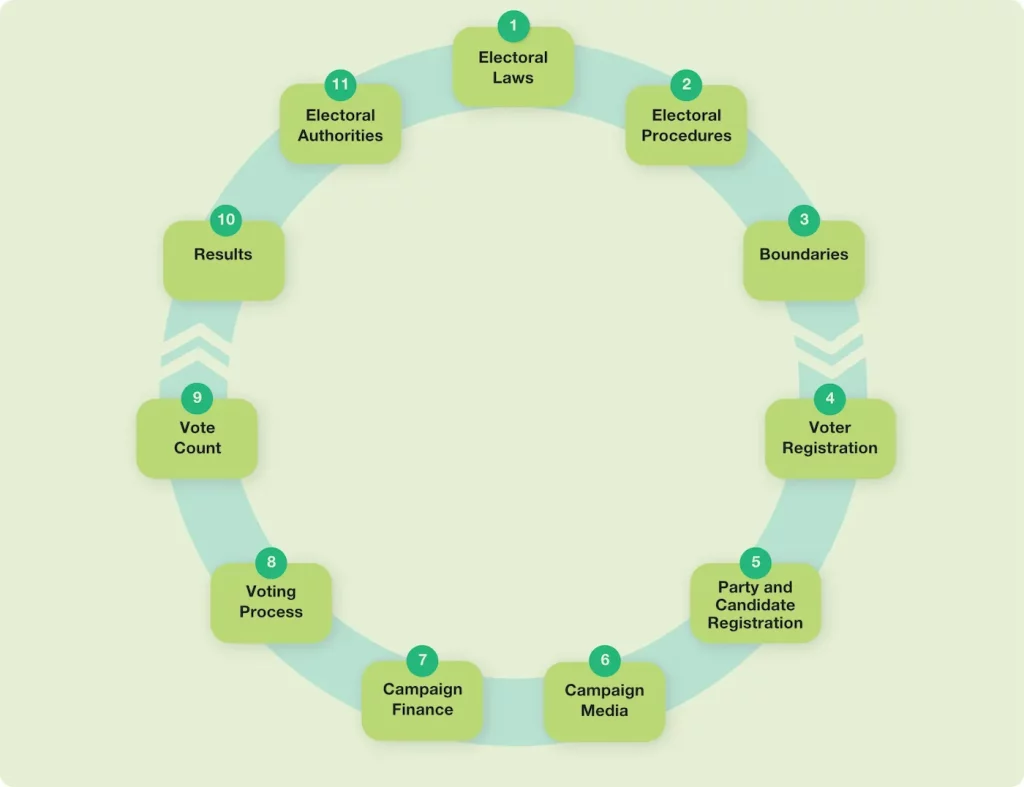

Election-related violence signifies the inability of Member States to establish consistent and peaceful transfers of power. Therefore, effectively managing election-related conflict necessitates thoroughly comprehending its diverse manifestations throughout the electoral process. Timothy Sisk2Timothy, Sisk (2008) ‘Elections in Fragile States: Between Voice and Violence’, paper prepared for the International Studies Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, California, 24–28 March. observes that social structure, political competition, the effectiveness of electoral administration, and the level of professionalism in the security sector actively shape election-related conflict. This article uses an electoral cycle approach (see Figure 1) inspired by Pippa Norris, Richard W Frank and Ferran Matinez i Coma’s (2014) work, ‘Measuring Electoral Integrity around the World: A New Dataset’.3

Norris, Pippa; Frank, Richard W.; and Martínez i Coma, Ferran (2014) ‘Measuring electoral integrity around the world: A new dataset’, PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(4): 789–798. Norris et al. note that: The international community has adopted the electoral cycle approach as the gold standard, recognizing that parachuting observers to scrutinize only the end processes of balloting, vote count, and results is too limited unless a longer-term assessment of each contest also takes place. Attention often focuses on the finish line, but like a marathon, elections may be won or lost at the starting gate (p. 790). Utilising the electoral cycle approach, which delineates critical phases and associated patterns of violence within an electoral cycle, proves advantageous for those seeking to enhance the quality of elections and mitigate the recurrence of violence and intimidation.

Source: Pippa Norris, Richard W Frank and Ferran Matinez i Coma (2014)

The electoral cycle approach4Ibid, p. 790. identifies specific types of violence linked to the various stages of the electoral cycle. During the pre-election period, characterised by voter registration and campaigning, violence is often employed to manipulate voting patterns through voter intimidation and heightened insecurity. The polling phase may exhibit varying intensity, as seen in Zimbabwe’s seemingly calm polling days despite preceding violence5Sithole, Tinashe (2020) ‘The 2018 Harmonised elections in Zimbabwe-an example of electoral democracy?’ Africa Insight, 49(4): 136–152. in the 2000 and 2008 elections. The immediate post-election period between voting and result proclamation is considered particularly dangerous, as are outcomes and their aftermath when election disputes, perceived as fraudulent or stolen, anticipate violence that can escalate into armed conflict or civil war.

The causes of election-related conflict are context-dependent, requiring diverse conflict resolution mechanisms. The interplay of agency (individual actions) and structure (broader social, political, and institutional forces), central to election-related conflict and regional intervention outcomes, adds complexity to explanations. This article posits that the agency and structure are necessary towards understanding the causes of election-related conflicts and should be considered in regional interventions. Regional organisations, guided and mandated by various protocols, intervene despite challenges. Chikwanha and Masunugure note that: ‘third parties very often lack the details of the conflicts they mediate’, leading to ‘short-lived peace deals. Perceptions of biasness also affect decisions made by regional organisations and this has serious implications on the peace deals they propose.’6Chikwanha, Annie B. and Masunungure, Eldred V. (2012) ‘The African Union and election-related conflicts in Africa: an assessment and recommendations’, Journal of African Union Studies, 1(1): 41–60, p. 44; Nsibirwa, Martin and Mhodi, Peacemore (2017) ‘Coup, what coup? The vexing question of how SADC and the AU should react to Zimbabwe’s situation’, Daily Maverick, 22 November, Available at: <https://allafrica.com/stories/201711220207.html> [Accessed on 23 October 2023]. Nsibirwa and Mhodi note that there is a widespread view, especially among Zimbabweans, that SADC has failed in its previous interventions in Zimbabwe; hence it should not involve itself in the current political and constitutional impasse there. Depending on the power dynamics, regional interventions contribute to a political culture emphasising dialogue, bargaining, and compromise in peacemaking. However, SADC’s effectiveness in containing contemporary election conflicts remains a critical concern, especially given the propensity of security forces in African countries to exceed their election-related mandates. Political leaders may influence security forces to manipulate elections in their favour. For instance, there have been allegations in the past that during national elections, security forces in Zimbabwe have engaged in activities like voter intimidation, harassment of opposition figures and supporters, and biased enforcement of election laws.7Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2023) ‘Zimbabwe revisits its “ugly past” of violence and intimidation’, Available at: <https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/06/07/zimbabwe-revisits-its-ugly-past-violence-and-intimidation> [Accessed on 22 November 2023].

Normative frameworks guiding the conduct of free and fair elections

‘The Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa,’8Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA) (2002) ‘Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa’, AHG/Decl.1 (XXXVIII), Available at: <https://www.eisa.org/pdf/au2002declaration.pdf> [Accessed on 23 October 2023]. adopted in July 2002 during the Organisation of African Unity (OAU)/AU’s 38th Ordinary Session, responded to the escalating electoral violence. Chikwanha and Masunungure note that, ‘Decision EX.CL/Dec.300 (IX) led to the creating of the Democracy and Electoral Assistance Unit (DEAU) in the AUC’s [African Union Commission] Political Affairs Department, established after the 2006 Executive Council decision in Banjul.’9Chikwanha and Masunungure (2012) op cit. The DEAU, a technical unit for election capacity building, plays a pivotal role in standardising election conduct and is a potential hub for early warning of electoral conflicts.

The DEAU’s decision to dispatch an observer and monitoring mission during elections is based on a preliminary assessment of the country’s social, economic, political, and constitutional conditions. The AU Electoral Assessment Team advises the DEAU to proceed with a mission. The pre-election observation period allows for the detection of ‘hot spot’ areas prone to violence, enabling early conflict mitigation efforts and reducing casualties. In addition, both the Panel of the Wise (POW) and the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) country reports contribute significantly to the pre-election assessment, serving as valuable sources of information. They enhance the fact-gathering process, providing crucial input for mitigating potential election conflicts. However, the process may face delays because these organs report directly to the Heads of State.

The AU’s commitment to improving democratic practices has its roots in the OAU era, but leaders at the national level have taken time to embrace these efforts fully. Legal frameworks and guidelines, such as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) and regional protocols like the 2015 SADC Protocol and Guidelines Governing Democratic Elections, actively promote best practices in election management. Adhering to these standards helps prevent violence, encouraging political tolerance, acceptance of election results, and the lawful challenging of results. Despite the collective will within the AU, the individual behaviours of presidents at the national level do not always align with the values reflected in AU agreements, indicating a gradual internalisation process of these democratic principles.

Factors contributing to electoral conflicts in Zimbabwe

Elections across Africa encounter significant challenges throughout various stages. Peace negotiations in conflicts related to elections encounter challenges similar to those in post-war peacebuilding. These challenges involve navigating the complexities of the conflict, adhering to the imperative of non-interference in state affairs, and addressing the absence of credible institutions to implement and enforce peace accords.

The involvement of the security sector, particularly the military and police, in electoral processes remains a significant challenge in Zimbabwe and other developing countries.10Chitiyo, Knox (2009) ‘The case for security sector reform in Zimbabwe’, Royal United Services Institute; Chikwanha, Annie B. (2022) ‘The liberation culture and missed opportunities for security sector reform in Zimbabwe: 1980–2018’, African Security Review, 31(2): 123–138. Security sector actors, often untrained for electoral processes, face political pressure to compromise their professional conduct. Unlike in many democratic countries where the military stays in the background, in conflict-prone nations, they play a role in maintaining law and order during elections, testing the civil-military relations. The military often becomes partisan and aligns with the regime, leading to their involvement in voter intimidation activities against perceived opposition. Since 2002, Zimbabwe’s security sector has intervened in elections, tilting the playing field in favour of the incumbent, raising concerns about intrusion into civil and political spaces, intimidating voters, and hindering democratic development.11Chitiyo (2009) op. cit. Amidst the political turmoil post-2002, the Defence Forces Commander established the Joint Operations Command (JOC) in 2007.12Chikwanha, Annie B. (2022) ‘The liberation culture and missed opportunities for security sector reform in Zimbabwe: 1980–2018’, African Security Review, 31(2): 123-138, DOI: 10.1080/10246029.2021.1960401. This included leaders from the National Army, Prison Services, Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP), and Air Force of Zimbabwe. This move empowered the army to exert control over all the country’s productive sectors. Consequently, Zimbabwe’s military and security forces have been accused of intervening in political and electoral affairs, backing President Robert Mugabe and his party, ZANU-PF, and curtailing citizens’ rights to free expression, association, and voting.13HRW (2013) ‘The Elephant in the Room: Reforming Zimbabwe’s Security sector ahead of Elections’, 4 June, Available at: <https://www.hrw.org/report/2013/06/04/elephant-room/reforming-zimbabwes-security-sector-ahead-elections> [Accessed 22 November 2022].

Power-sharing agreements, proposed by SADC and endorsed by the AU, in Zimbabwe undermined confidence in African electoral democracy, particularly when the incumbent, despite indications that they lost, retained power.14Mapuva, Jephias (2013) ‘Governments of national unity (GNUs) and the preponderance of the incumbency: case of Kenya and Zimbabwe’, International Journal of Political Science and Development, 1(3): 105–116. In addition, the failure to implement provisions in the 2008 Global Political Agreement (GPA) highlights this scepticism. SADC’s resolutions on Zimbabwe, expressing disappointment in the GPA’s insufficient progress, underscore challenges in enforcing political agreements. The AU’s response to disputed elections on the continent raises questions about its political will to hold leaders accountable and the efficacy of the African Court of Human Rights in adjudicating contested election results. The AU’s approach, often perceived as an incentive for unpopular leaders to maintain power through fraudulent elections, leaves other AU bodies passive, aligning with the non-interference and supreme sovereignty principle.

SADC interventions in Zimbabwe

Since removing Mugabe from power in 2017, Zimbabwe has undergone two elections in 2018 and 2023, both marred by controversy.15Muronzi, Chris (2023) ‘Zimbabwe: Story of a stolen election’, Financial Mail, 31 August, Available at: <https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/features/africa/2023-08-31-zimbabwe-story-of-a-stolen-election> [Accessed on 23 October 2023]. The 2018 elections faced credibility challenges, leading to state-sponsored violence and at least seven casualties at the hands of the army.16Sithole (2020) op. cit. The absence of electoral reforms and disputed election results further fuelled the controversy. In 2023, the SADC observer mission, under the leadership of Dr Nevers Mumba, identified electoral irregularities and highlighted deficiencies in adhering to democratic principles and guidelines in its preliminary report. Both African and Western foreign observers criticised the election irregularities.17Ibid.

The response from ZANU-PF and SADC leaders to the SADC report was perceived as weak, delayed, and unsatisfactory. This raised concerns that the regional body did not strongly condemn the incumbent regime’s election misconduct. The reaction from SADC leaders was criticised for being insufficiently assertive in addressing the challenges in Zimbabwe, suggesting a passive approach rather than a proactive response to the issues at hand.

An assessment of SADC’s approach and response to election-related conflict

The effectiveness of SADC’s intervention in election disputes is contingent upon several factors. One crucial determinant is the timing of SADC’s involvement, explicitly pinpointing the stage within the electoral cycle when intervention occurs. Furthermore, the country’s size is crucial, given that elections occur nationwide, involving diverse regions and populations. This complexity necessitates a strategic evaluation by external entities like SADC to identify the most opportune and effective moments for intervention. Thus, the logistical and operational challenges associated with larger countries impact the timing and approach to any external involvement in the electoral process. Despite the recurrent instances of election violence in Zimbabwe, SADC has adopted an approach centred on indirect diplomatic tactics.

SADC’s hesitancy to adopt a more direct and assertive stance, particularly when Member States deviate from democratic principles, can be attributed to the unique challenge posed by SADC Member States’ liberation movement solidarity. This solidarity presents a formidable obstacle to meaningful intervention, especially in cases where elections deviate from the established SADC principles and guidelines governing democratic elections. In the context of Zimbabwean elections, which consistently manifest violence across various phases of the electoral cycle, except during the actual polling process, there is a compelling argument for sustained SADC and AU intervention and presence throughout all electoral stages.

The contention is that the protracted nature of election-related violence in Zimbabwe has generally necessitated comprehensive long-term observer missions by both SADC and the AU, spanning the entire electoral process, with a specific emphasis on the period extending from three to six months into the post-election period. Consequently, evaluating SADC’s effectiveness in election dispute resolution must include a consideration of these factors, acknowledging the complexities inherent in addressing election-related challenges in the region.

Recommendations to improve SADC’s engagement in electionrelated conflict

Addressing challenges in African elections prompts a crucial question: What actions are needed? This question needs more straightforward answers. The article recognises that conflict and electoral violence contribute significantly to the ‘Afro-cynicism’ surrounding the continent, leaving a lasting impact on Africa’s political landscape. Two key points are emphasised: the complexity of election-related violence requires a comprehensive, multi-stakeholder approach, and there is no immediate, all-encompassing solution.

In terms of agency, the key actors are identified as Electoral Management Bodies (EMBs) and national security services. While the AU and Regional Economic Communities (RECs) concentrate on EMBs, there is a critical need to direct additional focus on national security services. Instances of election-related violence are often linked to inappropriate actions by EMBs, emphasising the urgency of addressing challenges within both EMBs and national security services to utilise the AU’s resources effectively. Therefore, it is important for allocating resources to critical aspects of the electoral process, ensuring transparency, and coordinating efforts at various levels.

Transparency, especially in the actions of EMBs, is underscored as crucial to prevent electoral problems. Efficient coordination at different levels is deemed essential for achieving desired electoral outcomes. Additionally, the article underscores the pivotal role of security services, urging SADC to acknowledge their significance in maintaining democratic governance and adhering to electoral conduct standards. Integrating electoral security into the broader human security framework, prioritising civilian protection during elections, and compelling Member States to ensure security service impartiality throughout the electoral process are identified as essential steps.

Conclusion

Inefficient coordination among AU RECs hinders collaborative efforts in effectively addressing electoral conflicts. The institution’s delayed response time, limited capacity, and apparent reluctance to deploy mediation teams promptly contribute to prolonged conflict resolution and increased civilian deaths in the context of elections. SADC’s weak intervention capacity results from a demonstrated lack of political will among SADC leaders. Despite its supranational status, SADC often functions more as a coordinator of sovereign African states, and its diplomatic approach, aimed at allowing Member States to resolve disputes independently, has proven ineffective in election-related conflict situations. A more proactive, collaborative, and expedient approach is necessary for better and sustainable protection of citizens during electoral conflicts.

Dr Tinashe Sithole is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the SARChI Chair: African Diplomacy and Foreign Policy at the University of Johannesburg.