Introduction

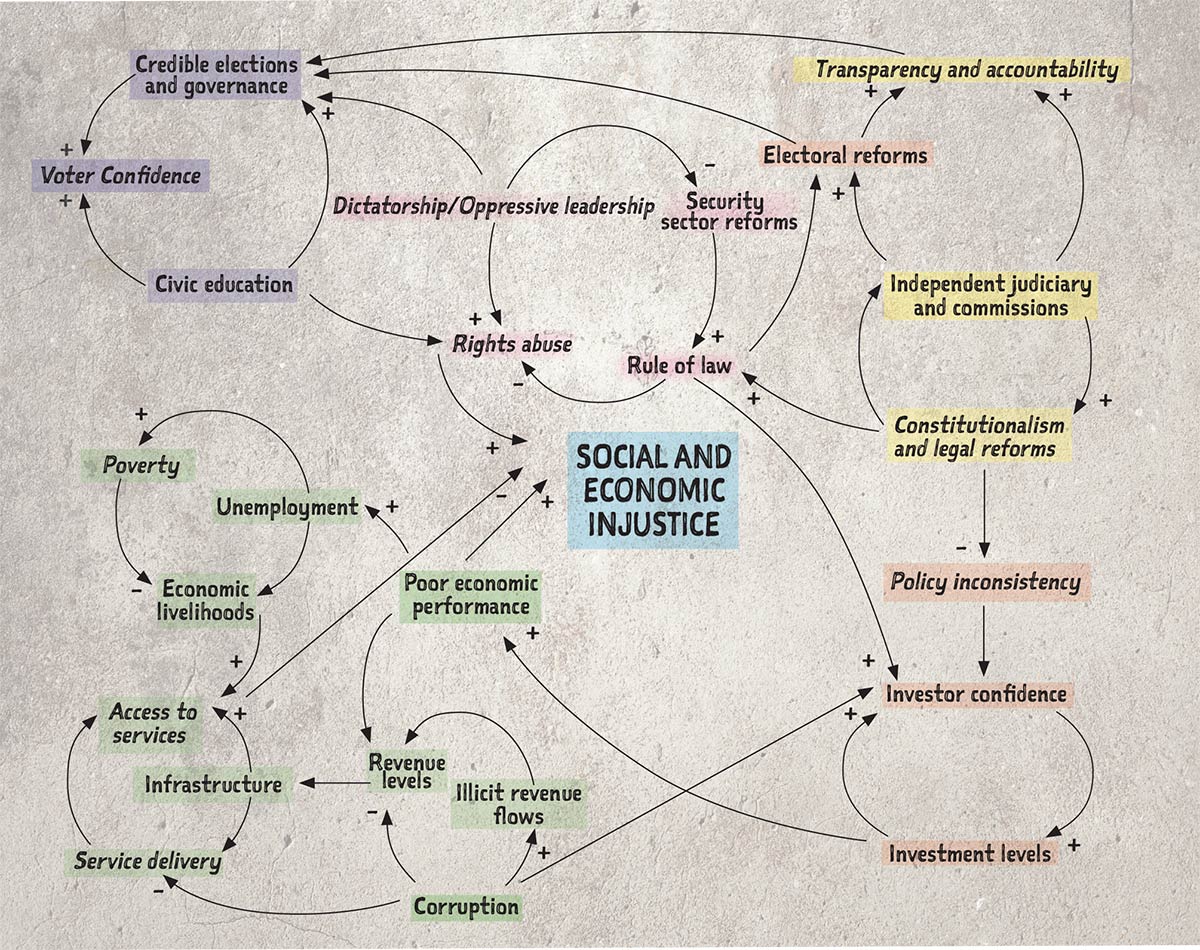

Zimbabwe has experienced different forms of conflicts since independence in 1980. It is appropriate to apply a systems approach for us to unpack Zimbabwe’s conflict to date. The causal loop diagram (CLD) in Figure 1 summarises the conflict.

The CLD clearly indicates that Zimbabwe’s conflict is a complex web of sociopolitical and economic challenges. These include issues such as poor service delivery, corruption, poverty, unemployment, poor economic performance, policy inconsistency, lack of independence of the judiciary, lack of rule of law, human rights abuse, dictatorship, lack of civic education, reduced voter confidence and issues with the credibility of elections.

Zimbabweans have experienced structural and cultural violence. Structural violence equates to social inequality and leads to impaired human growth and development.1 Cultural violence is the rhetorical excuses that usually follow government’s failure to act or deliver on ensuring that its citizens live good lives in all spheres. Structural violence delays self-actualisation and, in most cases, people always fall short and fail to reach optimum potential realisation. For the purposes of this article, structural violence and cultural violence will be taken to imply the policies and statutes that are put in place in a country whose intentions were to do good, but instead they bring harm to the citizens.2 It will also refer to the actions related to the enforcement of such policies to the extent of infringing on the human rights of citizens. Structural violence usually occurs in public institutions such as the legal system, education, health services and other public empowerment initiatives undertaken by the government.

There is also a perpetuation of an entitlement mentality among different groups within the ruling party, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF).3 Members seem to have a right to access a number of resources such as land, loans, farming equipment or food handouts, since they are distributed by the ruling party and only members benefit. This promotes a retributive stance by those who have been alienated and victimised. They harbour resentment, anger and vengeance. Failure to address the underlying causes of the existing challenges that many Zimbabwean citizens face can easily lead to a mobocracy.

The people of Zimbabwe have internalised these forms of violence, accepting them to be a normal way of life. However, this state of negative peace is punctuated by hushed and unexpressed anger. The citizens’ discontent with any situation, public or private, is heard through murmurings behind closed doors and in corridors, but never publicly. This leads to them accepting the continued justifications given by policymakers and politicians for the government’s lack of action; a form of cultural violence in its own right.

Non-violent Strategies as the Option for Dealing with Zimbabwe’s Conflict

Whilst gravitating to violence might come naturally for the people of Zimbabwe, there is a realistic, alternative, non-violent option to deal with conflict or even strong repression.4 Non-violence is the appropriate option in Zimbabwe, since the freedom of expression through public events such as demonstrations, marches or merely community discussions is hampered by draconian laws such as the Public Order and Security Act (POSA). Any authorised public meetings are monitored and have resulted in a number of arrests, should the discussions or events skirt on matters deemed to be political. Civic activities are carried out in an atmosphere of intimidation and fear. The failure of activists to apply non-violent strategies result in them falling into the government’s trap of breaking laws, and such actions will therefore likely be met with hard-handedness through police brutality, arbitrary arrests, abductions and, at times, the disappearance of activists.

Experiences of the Youth in Zimbabwe

Adult idealism sees the youth as lacking knowledge and experience, and they are thus unwilling to give the youth much political space. Sometimes, violence is employed to thwart youth participation. However, McEvoy-Levy5 states that the youth are innovative, possessing and utilising different forms of power and expressing themselves through different peacebuilding activities. There are growing calls to support the efforts of innovative young activists and peacebuilders in addressing the challenges that the youth face daily. However, doing so is often dismissed as political mischief and a push for regime change in a country such as Zimbabwe. Sadly, most – if not all – political parties in Zimbabwe are guilty of closing out the political space for the youth. Politicians in Zimbabwe prefer to provide limited political space to the youth, and restrict them to their youth league formations. The modus operandi is to deprive the youth socio-economically and render them susceptible to exploitation and control by the “empowered” few in the political hierarchy who have the political and financial muscle to purchase the energy of the youth. It therefore follows that being able to address the social inequality challenges faced by the youth limits the ability of politicians to convince the youth to participate in violent acts.

The Youth are Finding their Voice and Speaking Out

The year 2016 has seen unprecedented historic events unfold in Zimbabwe as young people begin to find their voices and speak out against injustices in the country. Citizens have started to speak out against their government amid rising calls for socio-economic and political transformation. Some of the events that have triggered this backlash from young Zimbabwean citizens across the globe are listed below.

| Period | Occurrence/Trigger Events |

| January 2016 | Statutory Instrument 148 of 2015 [CAP. 23:02] Customs and Excise (General Amendment) Regulations, 2015 (No. 80), which reduces the duty rebate for travellers to US$200 from US$300 whilst, at the same time, completely scrapping it for travellers using small cross-border transport, buses or trucks, is operationalised. |

| March 2016 | It was reported that President Robert Mugabe revealed, during his 91st birthday interview, that Zimbabwe was robbed of more than US$15 billion in revenue from diamond mining in Chiadzwa by the companies that were running the mining business in the area. |

| April 2016 | The Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education introduced the Schools National Pledge. |

| May 2016 | The governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe announced a plan to introduce bond notes, as a measure to address the cash crisis facing the country. |

| June 2016 | Statutory Instrument 64 of 2016, which bans the import of goods without a licence, was introduced. |

The general trend in passing some of these laws was the lack of transparency and consultation by the government. The subsequent imposition of these measures angered citizens, many of whom viewed them as further spiralling the poor into poverty. Young Zimbabweans were angered in reaction to these measures, the lack of transparency and accountability with regard to the missing US$15 billion and the failure to deal with increasing levels of corruption. Youth activists reacted by increasing their mobilisation activities and starting to use social media platforms to voice their displeasure with the government.

Movements Championing the Cause of Zimbabwean Citizens

A number of increasingly recognised movements have sprung up in Zimbabwe as youth activism sweeps across the country. Three of these movements are Occupy Africa Unity Square (OAUS), #ThisFlag Movement and the Tajamuka/Sesjikile Campaign.

Occupy Africa Unity Square

OAUS is a movement that identifies itself as “a group of citizen activists founded by Itai Dzamara in 2014”.6 The movement is driven by non-violence and a principled and constitutional fight to liberate the country from corruption and mismanagement. Its members believe they have a duty to carry on the struggle started by Zimbabwe’s liberators as they accomplish and protect Zimbabwean freedom, albeit by different means. The founder of the movement, Itai Dzamara, has been missing since 9 March 2015, when he was abducted by unidentified men outside a barber shop in his neighbourhood.7 His brother, Patson Dzamara, has become the face of OAUS and together with other members, continue to use Africa Unity Square in Harare as their main protest venue. In June 2016, 15 activists were arrested as part of a clampdown on the 16-day OAUS protest, which they had started on 1 June 2016.8

#ThisFlag Movement

The #ThisFlag Movement started through a monologue video recording shared by Pastor Evan Mawarire on 20 April 2016 via social media platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter.9 In his recording, Mawarire expressed his disappointment at the Zimbabwean government’s failure to create an environment where he could provide for his children’s education and upkeep. He went on to call on Zimbabwean citizens across the world to share photographs via “selfies” showing themselves holding a Zimbabwean flag, in protest to the corruption and social injustice prevailing in the country. The video went viral on social media and the response to his call for action was astounding.10 Zimbabwean citizens from all over the world shared their selfies in protest. In June 2016, he took the protests further by inviting citizens to a meeting with the governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, where they expressed their disapproval of the introduction of bond notes. In the same month, the #ThisFlag Movement also started a petition to have the Minister of Energy and Power Development in Zimbabwe removed from office for corruption. The movement galvanises citizens in Zimbabwe and abroad to demand non-violently that the Zimbabwean government act to curtail the country’s socio-economic challenges. The movement’s main demands are an end to corruption, increased government transparency and accountability, and the creation of platforms for engagement between the government and citizens. One of the major achievements of the movement so far was the calling of a successful stayaway, dubbed #ShutDownZimbabwe2016, on 6 July 2016. The call to stay away coincided with strikes by teachers and commuter omnibus operators, which helped to make it a big success.

Tajamuka/Sesjikile Campaign

This campaign was started in May 2016 by a group of young people perturbed by the events in their country. The words tajamuka and sesjikile are Zimbabwean vernacular – which, when loosely translated, means “that we have rebelled”. The campaign is “a gathering of 15 youth wings of the various political parties in Zimbabwe and more than 40 civic society organizations, churches, youth movements informal sector pressure groups, and labour and student movements”.11 Tajamuka was born out of the desire to bring sanity, development and accountability, and to give the people of Zimbabwe a voice in the running of the country, with the primary aim of forcing Mugabe to step down before the general elections, to be held in 2018. The members maintain that they are not a political party or group. They state that they are simply youth who are acting together in defence of their country from erstwhile liberators, who have lost the ethos of the liberation struggle and robbed them of the very freedoms they claim to have fought. Tajamuka/Sesjikile takes its campaigns to the streets of Zimbabwe and is involved in different action across the country. It is guided by the following 10 principles:

- No to bond notes.

- We want our 2.2 million jobs.

- The missing US$15 billion must be returned.

- An end to corruption.

- Cash crisis must be resolved urgently.

- Itai Dzamara must be returned to his family, and there must be an end to forced disappearances, illegal arrests and detention, and state-sponsored violence.

- Social services delivery must improve.

- No to the national pledge.

- Devolution of power now.

- We want the missing US$10 million for the Youth Fund.

In June 2016, members took to the streets to address citizens in queues outside banks, and called on them to speak out against the failures of the Zimbabwean government. Members were also involved in protests against the import ban of goods, which led to the closure of the Beitbridge border post. Some Tajamuka/Sesjikile members were arrested and accused of burning down the customs warehouse at the border. The Tajamuka/Sesjikile Campaign also claimed credit for having taken part in the street protests of 6 July 2016. In some of the protests, the police fought running battles with protesters in various locations across Zimbabwe. Since this is a loosely structured campaign, it is easier for it to be associated with any youth-led street protests occurring across Zimbabwe. The Tajamuka/Sesjikile Campaign has laid claim to a number of such protests, and has also been accused by the police of fuelling violent protests countrywide. The campaign gave the president until 31 August 2016 to either resign or lay out a plan to hand over power to someone else. It warned that failure to do so would result in the protests being taken to a higher level.

Challenges of Youth Activism in Zimbabwe

The biggest challenge observed in the ongoing youth activism activities in Zimbabwe is their piecemeal approach to doing things. An analysis of the demands made by the #ThisFlag or OAUS movements, as well as Tajamuka/Sesjikile’s 10 principles, shows that they are all advocating for the same things. What differs, then, is the manner in which they are laying out their demands and taking action. The former two movements rely mainly on social media, whilst the latter has used the streets as its rallying point. The failure by these activists to unite and undertake a combined campaign is a weakness that can be capitalised on by the very government they are tackling. This lack of unity can be the Achilles heel that could lead to the demise of youth activism before their demands are met. Another challenge is the spontaneity under which most of the action has taken place. Leaders in the many movements in Zimbabwe right now need to be more strategic and organised. The activists show this weakness through their failure to plan for and deal with the arrests of protesters. They have no means of following and tracking protesters who were arrested, so as to reduce the opportunities for abductions and disappearances. They also lack plans on how to bail out protesters, which has led to a number of people spending days in remand after failing to raise bail money. “Improving the strategic performance of leaders in nonviolent action improves the efficiency and effectiveness of the technique”.12

The Arrest of Pastor Evan Mawarire of the #ThisFlag Movement

Whilst many other youth leaders and protesters have been arrested in Zimbabwe, the arrest of Pastor Evan Mawarire on 12 July 2016 deserves special mention – as in the process of his arrest, the police and the government of Zimbabwe hindered themselves. Mawarire was arrested on the eve of the planned second set of stayaway protests, on charges of inciting violence and being in possession of a police helmet and baton. However, on appearing in court, a different charge – of trying to remove a constitutionally elected government – was levelled against him. His arrest is significant as it tested the level of unity among Zimbabwean citizens and across civic society movements. How citizens in Zimbabwe and across the world reacted to this arrest was unprecedented. Close to 100 human rights lawyers turned up to represent Mawarire, pro bono.13 And whilst initially a few hundred supporters, draped in the national flag, showed up at court in the early hours of the day on 13 July 2016, the number swelled to around 5 000 by the time judgment had been passed.14 Citizens across the world rallied behind the youth activist, and messages of support and mobilisation flooded social media. People waited outside the court in solidarity, showing unity and vowing not to leave until Mawarire was released. The magistrate threw out the case on the basis that the state’s conduct was unconstitutional.

The events on the day that Mawarire was arraigned before the magistrate’s court was an indication of a people who have been galvanised and empowered to speak out. Citizens mobilised themselves using social media platforms – a sign of the power that social media can have in getting messages across. Social media has become the tool that citizens can easily access and use to voice their frustrations against the regime. The united stand also reflects the ability of Zimbabweans to come together and support one cause – something that has been missing in the quest to bring about political and socio-economic change in the country over the past few years. It also marks a turnaround in the Zimbabwean political and civil society sectors, where a focused front to push the president and his government out of office can now emerge. Coalitions and collaborations should emerge in the next coming months as both political and social movement leaders take advantage of a mobilised and united citizenry yearning for change.

Conclusion

Zimbabwe finds itself at a crossroads, as many of its citizens are asking themselves what the way forward is in dealing with their conflict. Youth activists and leaders of political and civic movements have to decide on the course of action to take. Whilst a number of options present themselves, the citizens of Zimbabwe should adopt peaceful and non-violent means to express their views. Failure to do so will lead to more arrests, and likely the declaration of a state of emergency. Non-violent action assumes that “if people carry out the action long enough and in sufficient numbers it will lead to an oppressive government becoming powerless and receding”.15 Leaders of movements must take advantage of the unity displayed in the arrest of Mawarire and cross-pollinate their ideas and approaches. They must desist from spontaneity only and become more strategic and organised in the actions they take. There is need to train activists on how to lead strategic non-violent actions across the country. Activists need to be made aware of the many tried and tested non-violent actions they can adopt that do not require citizens to take to the streets and put themselves in immediate harm and danger – for example, consumer boycotts.

On the other hand, the conflict cannot be ignored any longer by the Zimbabwean government, or by neighbouring countries. As more youth become agitated, the conflict has the danger of spurring radicalism and can easily break out into a civil war if not immediately addressed. It can affect the entire region’s stability and increase the numbers of economic and political refugees who flee to other countries. If left unchecked, the Zimbabwe crisis can increase the levels of social injustices in the country, with significant spill-over effects into the southern African region.

Endnotes

- Galtung, Johan (1969) Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), pp. 167–91.

- Webel, Charles and Galtung, Johan (2009) Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies. New York: Routledge, pp. 30.

- Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) is the political party that has been ruling Zimbabwe since its independence in 1980.

- Sharp, Gene (2003) There are Realistic Alternatives. Boston: Albert Einstein Institution, pp. 1–54.

- McEvoy-Levy, Siobhan (2012) Youth Spaces in Haunted Places: Placemaking for Peacebuilding in Theory and Practice. International Journal of Peace Studies, 17(2), pp. 1–32.

- Occupy Africa Unity Square (2016) ‘Who are We?’ Social media post, Available at: <https://www.facebook.com/Occupy-Africa-Unity-Square-386483044833537/> [Accessed 16 July 2016].

- Pindula (2016) ‘Itai Dzamara’, Available at: <http://www.pindula.co.zw/Itai_Dzamara> [Accessed 29 August 2016].

- Kandemiri, J. (2016) ‘Police Arrest 17 Occupy Africa Unity Square Activists’, ‘Studio 7’, Voice of America Zimbabwe, 9 June, Available at: <http://www.voazimbabwe.com/a/zimbabwe-politics-occupy-africa-unity-square/3369472.html> [Accessed 16 August 2016].

- Pindula (2016) ‘This Flag Movement’, Available at: <http://www.pindula.co.zw/This_Flag_Movement> [Accessed 17 July 2016].

- Simon, A. (2016) ‘The Man Behind #ThisFlag, Zimbabwe’s Accidental Movement for Change’, The Guardian, 26 May, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/26/this-flag-zimbabwe-evan-mawarire-accidental-movement-for-change> [Accessed 16 July 2016].

- Tajamuka/Sesjikile Campaign (2016) ‘Tajamuka/Sesjikile Press Release 11/07/2016’, social media post, Available at: <https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=1243042832373964&id=1207194655958782> [Accessed 16 June 2016].

- Ackerman, Peter and Kruegler, Christopher (1994) Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. Westport: Praeger Publishers, p. 6.

- Mtila, A. (2016) ‘More than 100 Lawyers Stand Up for Zimbabwe’s Protesting Pastor’, CNBC Africa, Available at: <http://www.cnbcafrica.com/news/southern-africa/2016/07/13/more-than-100-lawyers-stand-up-for-zimbabwe%E2%80%99s-protesting-pastor/> [Accessed 16 August 2016].

- Viljoen, A. (2016) ‘Zimbabwean Christians Lead Historic Day of Prayer, Protest as Pastor Freed’, Gateway News, 14 July, Available at: <http://gatewaynews.co.za/zimbabwean-christians-lead-historic-day-of-prayer-protest-as-pastor-freed/> [Accessed 28 August 2016].

- Sharp, Gene (2013) How Nonviolent Struggle Works. Boston: Albert Einstein Institution, p. 17.