Orchestrating Peace

One of the world’s youngest nations, South Sudan, broke out into civil war in December 2013. The civil war was marked by persistent disregard for the sanctity of civilians, especially women and children. At the time of the conflict, both the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in Government (SPLM-iG) and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in Opposition (SPLM-iO) carried out massacres, which spread like wildfire across the country. Troops from both sides raped and slaughtered civilians, while government troops in Juba went door-to-door, seeking out opposition ethnic groups.

After several failed regional mediation attempts, neighbouring states and international partners pressured President Salva Kiir, SPLM-iO leader, Riek Machar, and former detainees to sign the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS)[1] in August 2015 in Addis Ababa.

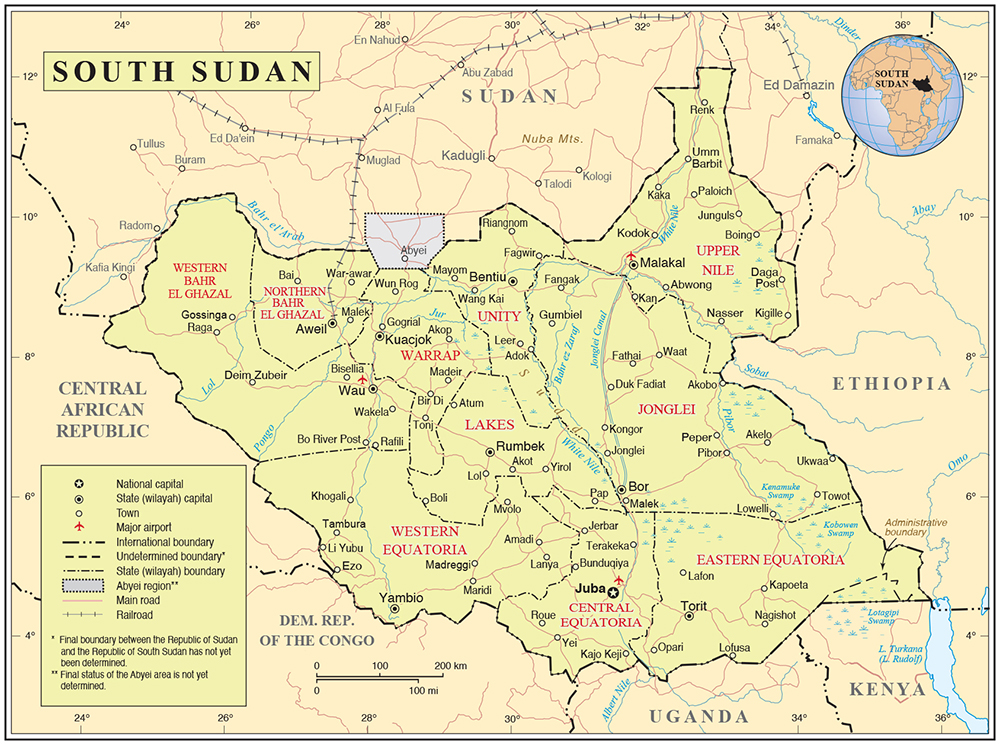

The Agreement aimed to end the violent civil war and support comprehensive political reform during a three-year inclusive Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU). Additionally, the ARCSS provided a pathway to demilitarise many well-equipped militias and mechanisms for transitional justice and reparation, immediate measures to facilitate humanitarian access, and a programme to redress the economy. Nevertheless, just after the ARCSS was signed, Kiir, by presidential decree, ordered an increase in the number of states from 10 to 28.[2]

Before the country could mark its fifth anniversary of independence, in July 2016, fighting broke out in Juba between the SPLA-iG and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army-in Opposition (SPLM/A-iO), killing over 300 civilians[3] and two United Nations (UN) peacekeepers.[4] Machar escaped Juba, fleeing to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)[5], only to end up under house arrest in South Africa. Weeks later, Kiir went on to form a government of unity without Machar, naming Taban Deng as Vice President. Kiir then issued another presidential decree to increase the number of federal states from 28 to 32 in January 2017, which further divided South Sudan’s states along ethnic lines, fuelling instability between the communities and the influx of local self-defence militias.

In September 2018, Kiir and Machar eventually agreed on a Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), which salvaged the 2015 peace agreement,[6] without accountability mechanisms and no penalties—and with Sudan and Uganda as guarantors. Both Sudan and Uganda have supported different groups during the country’s fight for independence. Twice, the signatories missed vital deadlines and delayed the formation of a TGoNU until its construction in February 2020. Following Machar’s agreement to return to Juba under the protection of the government without his forces and Kiir’s compromise with reverting the number of states to 10 (with three administrative areas), troops that were to be integrated into a unified national army were left abandoned for months in cantonment sites. In addition, Kiir refused to integrate his forces[7]and only allowed Machar to visit his troops in February 2021.[8]

The situation in South Sudan has not been helped by the government’s gender-blind policies that included the appointment of mainly male governors, deputies, and government officials[9] linked with the military.[10] While politics continues to be captured by the military and elites, many appointees lack technical expertise in the areas necessary to rebuild South Sudan and tackle existing challenges. Locally, institutions are either weak, non-existent or have been eroded due to prolonged conflict. The government’s response to communal violence has been to use threats of coercion against civilians as a strategy instead of comprehending the trauma experienced by civilians, building local capacity, and reconciling communities. Kiir even affirmed that he would stop sending troops to intervene in intercommunal fighting and let communities fight “until one section runs from the other”.[11] While much of the violence on display has been brought about by the government’s monopolisation and sanctioning of violence, its inability to protect civilians has led South Sudan down a dark path.

Dealing with the Past

To understand South Sudan’s weak governance, the SPLM/A’s monopoly over the state, and the way the SPLA and its elites exert authority, one needs to look to Sudan. Sudan’s colonial regime maintained its power through a combination of brutal military repression and strategies of division, identity politics, co-option and rulership.[12]

The post-colonial period encouraged the exploitation of resources, which had become the source of warfare, financing, and the very existence of the regime(s) in Sudan. Ultimately, resource exploitation became a warfare objective in itself.[13] The colonial system was later mastered by post-colonial regimes that mirrored these tactics and techniques through divide-and-rule campaigns and exploitation of peripheral territorial control, which later shaped the modern Sudanese state. Inevitably, this laid the groundwork for the post-colonial class formation and the rise of the northern bourgeoisie, who dominate Sudanese politics andadded a class dimension to the developmental state.[14]

This led to Sudan’s history of being dominated by military rule, overthrown by a popular uprising, a short period of democratic governance, quickly followed by another military coup, and so forth. Over 32 years, the two regimes, Nimeiri (1969–1985), overthrown by a popular uprising or Intifada, and the National Islamic Front (NIF) (1989–2004), revived old colonial policies and arrangements that would help Omar al-Bashir structure state power and transform modern Sudan into a state where northern elites abused resources outside of Khartoum for their benefit.[15]

Bashir and his regime dominated four critical components after the split of the NIF. The first was the National Congress Party (NCP), which had strong links to the Sudanese Islamic Movement. The Sudanese Islamic Movement’s religious ideology, which was made up of competing power centres, was an essential tool for Bashir’s regime stability. The movement imposed its ideological stance on the Sudanese population through coercion, purges, and strategic placement of leaders in unique civil servant positions across Sudan’s state institutions. The second was the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), which played a significant role in Bashir’s overthrow in April 2019. The NISS was later refashioned as the General Intelligence Services (GIS) in July 2019. The third was the Sudanese Armed Force (SAF), headed by Bashir and utilised to initiate most of his state powerprogramme. The fourth was the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), composed of elements of the Janjaweed,[16] under the leadership of Brigadier General Mohammed Hamdan Dagolo, referred to as ‘Hemedti’.

Competition between security personnel and elites created affiliated business groups that feed off state resources, crushing Sudan’s democratisation process, threatening transitional civilian rule, and curbing any future chances of a civilian government being formed. Under Bashir, paramilitary forces were used as a critical instrument of political power that supported the NCP’s motives. The discovery of oil and subsequent oil revenues enabled the regime to dramatically increase military expenditure, expand and upgrade military hardware, and use oil infrastructure to prosecute the war.[17]

Bashir allowed security segments to use these resources to finance their costs, expand their assets, and control state resources. The NISS, SAF, and RSF owned vast amounts of state resources. Both the NISS and RSF controlled companies that produced weapons, oil, gold, gum Arabic, wheat, telecommunications, banking services, water, banknotes,[18] and more. Military forces managed hospitals, trading companies, and financial commercial assets, which would be under the state’s control under normal circumstances. Under Bashir’s regime, Sudan’s economy was amplified by a system of external exploitation, using paramilitaries to remove populations from oilfields, gold mines, and neighbouring areas that were deemed rich in resources. Private elements were able to drain significant profits.[19] Bashir’s unique mix of authoritarianism with Islam and self-serving black-market economics shaped Sudan’s framework for restructuring state power and economic management.[20]

As a consequence of years of oppression across Sudan and Southern Sudan under Nimeiri, who served as president from 1969 to 1985, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) got underway, led by John Garang. The proposition of “two countries, one system” in Khartoum started to gain ground among elites. Still, Machar defected from the SPLA to form the SPLM/A-Nasir and demanded a vote for self-determination and independence. Machar later returned to the SPLA in 2005. This left the SPLA/M with a monopoly over safeguarding the interests of South Sudan. By controlling traditional and tribal leaders, the SPLA contributed to diminishing local governance but combined existing armies with competing allegiances as one. Just as a traumatised child can reproduce the behaviour of an abusive parent, the SPLA created a system of governance based on the oppressive practices of previous Sudanese regimes. This led to elite infighting, a lack of respect for diversity, and all-out civil war, where the actors competed for a monopoly over security and resources using identity politics.

South Sudan Today

The emergence of a new nation through military means was bound to fail peace in South Sudan. It is evident that while the peace agreements have always focused on the idea of civilian transition, these types of agreements often also maintain some form of military government. For peace in South Sudan to emerge, the state needs a professional, inclusive security apparatus organised without any loyalty to political elites, regional groupings, or ethnic communities. Most importantly, South Sudan’s security needs to be trusted, which means that the SPLA must be separated from the SPLM. Political parties should be allowed to emerge free from intimidation and not be dependent on militia groups.

A professional security apparatus should respect human rights, enforce the law, stop revenge attacks, diffuse communal disputes, and help build infrastructure across the country instead of killing the very civilians it was created to protect. However, given the SPLM/A’s history of questionable rule, it has always been clear that implementing the ARCSS and R-ARCSS under the SPLA/M would be difficult and likely never to be fully achieved.

Consequently, expecting that State debt, unemployment, underdevelopment, the inclusion of women and girls in society, and the impact of climate change and Covid-19 could be tackled by a military government is nothing short of a fantasy, given Africa’s experience with such military regimes. South Sudan’s military government lacks the competency and capacity to build the state. As a result, South Sudanese people will continue to experience undemocratic norms as long as its leadership focuses on individuals and elites only.

Towards Cohesive Governance

From 1972 to 1983, the South Sudanese managed the autonomous region’s affairs when other states were grappling with dictatorships and military coups. South Sudan has now undergone four experimental transitions (2005–2011, 2011–2013, 2015–2016, and 2018–present), each with mismanaged and unsuccessful transitional agreements, leading to further violence and insecurity. The South Sudanese are yet to forgive and reconcile among themselves, and hopes of a successful African Union Hybrid Court for South Sudan is nothing but a mirage, primarily when those who peddle violence will not be entirely held accountable. The world’s newest state has barely experienced good governance, constitutionalism, the rule of law, human rights, and gender equity, and asking a military government to achieve this with a weak and unchecked R-ARCSS is impractical and naive.

South Sudan needs a new civilian technocratic government that is people-centred and prepared to tackle, prevent and mitigate the root causes of conflict through long-term sustainable micro, meso and macro peacebuilding efforts. A new civilian technocratic government needs to rethink the state’s shared vision and shift the state’s responses away from just a security lens. To achieve this, the governing forces need to be reformed into an organism that institutionalises civilian oversight and legislative control. Civilian oversight can only be implemented when South Sudan strengthens its oversight mechanisms and executive authority over all security services.

International support is essential, but it is not sufficient to preserve peace in South Sudan. To an extent, the failed agreements have all shown that international pressure and the lop-sided focus on an incompetent government has undermined the autonomy and local ownership, which has a profound impact on the country’s peace-making practices. If international partners continue to recycle the same approach and templates that led us on the road to nowhere—that is, ceasefires that do not hold, weak transitional agreements, and flawed elections—then we can never expect South Sudan to emerge from conflict into a post-conflict state.

South Sudan’s peace process is still largely up for negotiation. A new South Sudan must emerge through a civilian technocratic government; however, this will require such a government to dismantle the SPLA/M and transform how security forces control the state. It also means effectively addressing the root causes of conflict and a people-centred approach to a transitional parliament, drafting a new constitution, deciding what type of federalism best suits the country, and strengthening the electoral commission in the short-to-medium term.

Dr Andrew E. Yaw Tchie is a Senior Researcher and Project Manager for the Training for Peace Project at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) and a visiting Professor at the University of Buckingham.

Endnotes

[1] Mesfi, Berouk (2015) ‘East Africa Report. The Regionalisation of the South Sudanese Crisis’, Managing Conflict in Africa, Available at: <https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/191757/E_Africa_Report_4.pdf> [Accessed 10 March 2021].

[2] Al Jazeera (2105) ‘South Sudan President Creates 28 New States’, <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/12/25/south-sudan-president-creates-28-new-states> [Accessed 13March 2021].

[3] UN News Centre (2017) ‘Killings, Rapes in South Sudan Continued “Unabated” after July 2016 Violence, UN Reports’, Available at: <https://www.un.org/africarenewal/news/killings-rapes-south-sudan-continued-unabated-after-july-2016-violence-un-reports> [Accessed 2 March 2021].

[4] BBC News (2016) ‘UN Sacks South Sudan Peacekeeping Chief over Damning Report’, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37840961> [Accessed 11 March 2021].

[5] The Guardian (2016) ‘South Sudan’s Opposition Leader Riek Machar Flees to DRC’, Available at:

<https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/18/south-sudan-opposition-leader-riek-machar-drc-democratic-republic-congo> [Accessed 2 March 2021].

[6] IGAD South Sudan Office (2018) ‘Signed Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan’, Available at:

<https://southsudan.igad.int/index.php/agreements/345-signed-revitalized-agreement-on-the-resolution-of-the-conflict-in-south-sudan> [Accessed 11 March 2021].

[7] UNMISS Press Statement (2021) ‘Statement of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General David Shearer to the Security Council on the Situation in South Sudan’, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/statement-special-representative-secretary-general-david-shearer-security-council> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[8] Eye Radio (2021) ‘Machar to Visit his Soldiers, Finally’, Available at: <https://eyeradio.org/machar-to-visit-his-soldiers-finally> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[9] Eye Radio (2021) ‘Kiir Reconstitutes Western Equatoria State Gov’t’, Available at: <https://eyeradio.org/kiir-reconstitutes-western-equatoria-state-govt> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[10] Eye Radio (2021) ‘Activist Criticises Kiir over Appointment of Deputy Governors’, Available at: <https://eyeradio.org/activist-criticizes-kiir-over-appointment-of-deputy-governors> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[11] Voice of America (2021) ‘South Sudan’s Kiir to Stay Out of Inter-communal Conflicts’, Available at: <https://www.voanews.com/africa/south-sudans-kiir-stay-out-inter-communal-conflicts> [Accessed 5 March 2021].

[12] Mamdani, Mahmood (2009) Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror, New York: Pantheon.

[13] Ali, Abdel Gadir; Elbadawi, Ibrahim; and El-Batahani, Atta (2005) ‘The Sudan’s Civil War: Why has it Prevailed for so Long?’ In Collier, Paul; and Sambanis, Nicholas(eds), Understanding Civil War: Evidence and Analysis. Volume I: Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.

[14] Tchie, Andrew E.Y. and Hamid, Ali E. (2021) ‘Restructuring State Power in Sudan’. The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 6(1), p. 41–51.

[15] Ibid. p. 45

[16] The Janjaweed militiamen are primarily nomadic ‘Arab’ tribes who over the decades were at odds with Darfur’s settled ‘African’ farmers. Under the Bashir regimes, this group was used to murder and slaughter Darfurians as part of the government’s strategy to destroy local militia forces.

[17] See Human Rights Watch (2003) Sudan, Oil, and Human Rights, pp. 59. Brussels: Human Rights Watch, Available at: <http://www.hrw.org/reports/2003/sudan1103/sudanprint.pdf> [Accessed: 21 December 2020]; Sharkey, Heather J. (2004) ‘Sudan: Oil and Water’. In Legum, Colin (ed.), Africa Contemporary Record, 27, 1998–2000, New York: Holmes & Meier; Taylor, Ian (2009) China’s New Role in Africa, London: Lynne Reinner.

[18] Gallopin, Jean-Baptise (2020) ‘Bad Company: How Dark Money Threatens Sudan’s transition’, European Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: <https://ecfr.eu/publication/bad_company_how_dark_money_threatens_sudans_transition> [Accessed: 23 September 2020].

[19] Suliman, Mohammed (1993) ‘Civil War in the Sudan: From Ethnic to Ecological Conflict’, The Ecologist, 23 (May–June), pp. 104–109.

[20] See Human Rights Watch (2003) op.cit.; Tchie, Andrew E.Y. and Hamid, Ali E. (2021) op.cit.