Introduction

Some developments in Africa during the first decade of this century ushered in a shared viewpoint within the African Union’s (AU) institutional space that one of the ways to propel sustainable peace within the African continent is through the forceful implementation of post-conflict reconstruction and development projects. This was a period when it became evident, both regionally and globally, that Africa would not achieve its desired prosperity and development unless sustainable stability was restored in a number of post-conflict states. In activating a coordinated effort to pursue a conflict-free Africa,2 AU policymakers placed priority on post-conflict peacebuilding activities.3 The first prominent action carried in this regard was the development of the AU’s Post-conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD) policy in 2006. Six years later, it became apparent to African regional actors that the visionary ideas embedded in the PCRD framework were utopian and unrealistic unless there was a clear demonstration of African self-reliance, leadership and ownership in the area of resource mobilisation for such a complex enterprise. This consensual acknowledgement invariably culminated in the launch of the African Solidarity Initiative (ASI) in 2012 as a flagship continental mechanism for mobilising resources within the African continent to build the institutional capacity of African states that were, and are, emerging from conflict.

However, despite the fact that different relevant organs of the AU considered the ASI as a necessary complementary and self-reliant mechanism for PCRD in 2012, seven years later it became an abandoned project. One of the implications of the atrophy of this African self-reliance programme is the renewed reality of inadequate resources and collectivist synergy that could strengthen the implementation processes of AU PCRD plans in post-conflict African states. In his report to the Peace and Security Council (PSC) on 22 March 2017, the chairperson of the African Union Commission (AUC) categorically stated that “the absence of financial and human resources remains a major obstacle to the implementation of the [AU] PCRD policy”.4 As informed by this background, this article explores three central questions. Why did the relevant organs of the AU consider the ASI as an indispensable framework for re-engineering PCRD in Africa in 2012, but a few years later it became a moribund initiative? Is it necessary to reactivate the ASI mechanism? What can be done to reinvigorate and institutionalise the mechanism for the implementation of the AU’s PCRD ideas? The need to examine these questions for clear policy direction is expedient, as African leaders are still striving for sustainable stabilisation in many post-conflict states.

The article is divided into four sections. The first and second sections unpack the AU’s pursuit of peacebuilding in Africa and the emergence and atrophy of the ASI respectively. The last two sections discuss why it is necessary to reactivate the ASI as an instrument for PCRD and how this can be achieved.

The African Union and the pursuit of post-conflict reconstruction and development in Africa

The transformation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) into the AU in 2002 was a remarkable development in the journey towards the strengthening and consolidation of African regionalism and cooperative engagement. It patently ushered in a new era of a shared commitment for a stable, strong and prosperous Africa.5 This happened both in terms of redesigning institutional frameworks and a collectivist commitment to key issues central to African growth and development. Not only did the policy agenda of a number of African regional economic communities (RECs) shift to accommodate peace interventions, but the AU as the central international organisation for pan-African cooperation also embraced a more expansive agenda in the area of security practices. Ensuring a peaceful and stable Africa became a cardinal priority of the AU. This was at the heart of the recognition by African regional actors that Africa as a continent cannot develop beyond the level of stability that is permitted across its vast territorial space. Over the years, this has tremendously reinforced the AU’s policybuilding in the area of peace and security. Many of the AU’s recent ambitious goals – such as “silencing the guns by 2020”,6 as encapsulated in its Agenda 2063 – are products of shared African thoughts that place security stability as the fulcrum of African development.

A prime concern of the AU in this context is how to prevent post-conflict states from relapsing into violence.7 This focus dates back to 2002, when the Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the AU was adopted. Article 3 of the Protocol expressly states that implementation of “peace-building and post-conflict reconstruction activities” will be a cardinal objective of the AU’s PSC.8 In actualising this objective, the AU decided to design its PCRD policy framework in 2006, following a thorough process of brainstorming and consultations. This marked a new phase of an AU policy-guided journey into the practice of post-conflict peacebuilding in fragile African states. The AU PCRD framework is an expression of African leaders’ dogged determination to take post-conflict peacebuilding seriously in their development of the “Africa they want”. The framework sets out the objectives, principles, elements, actors and resource mobilisation strategies of the AU PCRD programme.

The PCRD policy aims to provide clear guidance for preventing conflict relapse, addressing underlying triggers of conflict, executing reconstruction activities and facilitating coordination among different actors in the practice of peacebuilding in Africa. The key principles guiding the AU’s approach to PCRD are: “African leadership, national and local ownership, inclusiveness, equity and non-discrimination, cooperation and cohesion, and capacity-building for sustainability.”9 To demonstrate the comprehensiveness of African policymakers’ perspectives on what peacebuilding should entail, the AU PCRD framework recognises that post-conflict interventions need focus on different, but interconnected, issues across the security, political, humanitarian, socio-economic, gender, justice and human rights spheres. The framework demonstrates the ambitious vision of African leaders in the peacebuilding effort that concomitantly foregrounds short-term, medium-term and long-term action plans for more sustainable engagement.10 This was reinforced by an AU stakeholder when he noted that the AU approach to PCRD encapsulates three components of “stabilization, rebuilding and reconstruction, and development”.11 The framework equally demarcates responsibilities for actors at national, regional, continental and international levels to facilitate coordinated actions, subsidiarity and complementarity in the realm of post-conflict peacebuilding in Africa. The AU’s PCRD framework showcases more than just a policy. It reflects a pan-African vision in AU peacebuilding engagement that does not just stabilise a state after a period of conflict, but equally helps such a country to follow a path of comprehensive reconstruction and sustainable development. The reason for this visionary idea is understandable: if peace and stability can be sustained in every African country that is emerging from violence, then the African collective aspiration for a united, stable and prosperous Africa would, in a very short time, come to reality.

Notwithstanding the level of willingness and commitment attributed to this post-conflict reconstruction undertaking, especially at the continental level, some challenges confronted the AU in its endeavour to implement the ideas and measures that are explicitly set out in the PCRD blueprint. This became clear, particularly from 2012 onwards, when a number of post-conflict African countries could not be prevented from relapsing into conflict, despite the operationalisation of this framework.12 A central problem was inadequate resources,13 which mostly resulted from Africa’s overdependence on extra-regional partners for resources when discharging peacebuilding activities. In other words, effective implementation of the AU PCRD projects in Africa was contingent on a degree of African self-reliance in the realm of resource ownership. It was this realisation for the necessity of a mechanism to mobilise resources from within the African continent, to strengthen AU interventions in post-conflict countries, that led to the launch of the ASI in July 2012.14 This corroborates the contention put forward by Timothy Murithi that “adopting a strategy of coming together in the spirit of solidarity and cooperation is viewed by most African leaders as the only way forward,”15 especially for reconstructing war-torn African societies.

The emergence and atrophy of the African Solidarity Initiative

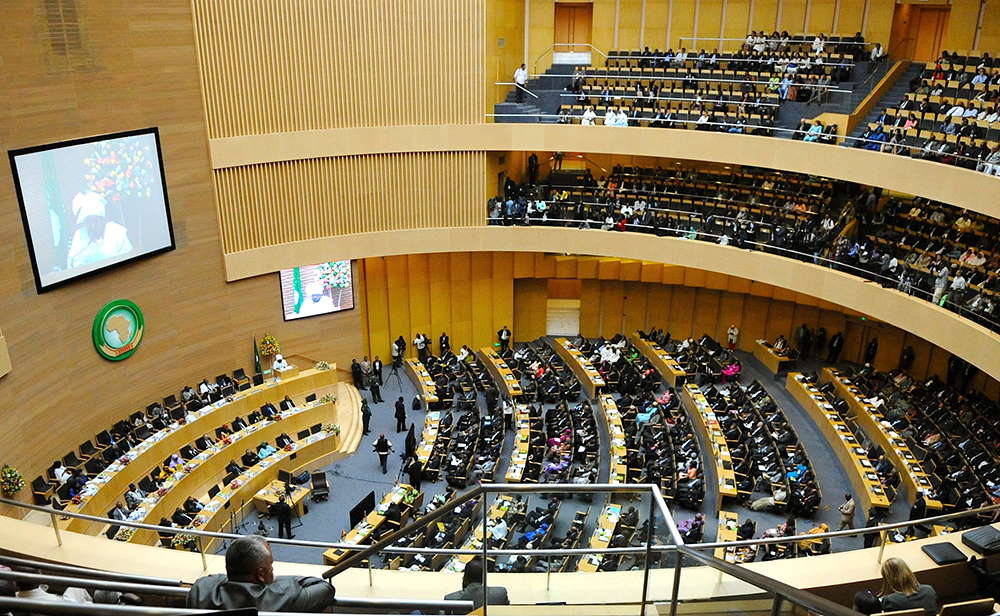

As a response to the urgency for an African self-reliance approach to peacebuilding in Africa, the ministers of foreign affairs of the AU member states officially launched the ASI on 13 July 2012, on the margins of the AU’s 19th Ordinary Session of the Assembly.16 This innovative mechanism was later endorsed by the AU Assembly; the highest decision-making body of the continental organisation. Based on the distinct characterisation of its purpose, the ASI was designed as the flagship scheme for mobilising both financial and in-kind resources from within the African continent for implementing the AU’s PCRD action plan.17 Some of the specific abridged objectives of the ASI include:

- “to deepen the essence of African solidarity and promote a paradigm shift which center‐stages African mutual assistance;

- to encourage, motivate, and empower African countries to offer support to post-conflict African states;

- to provide a unique opportunity for generating additional ‘out of the box’ ideas for addressing PCRD challenges, by actively involving African actors;

- to promote intra‐African solutions to the complex challenges of post‐conflict reconstruction;

- to contribute towards a renewed sense of urgency in consolidating peace where it has been achieved”.18

By and large, the ASI is a complementary mechanism that was devised to help African actors to look inward in the process of their collective attempts in supporting post-conflict African states to prevent costly relapse.

The ASI was informed by the urgency to activate “the spirit of pan-Africanism, solidarity and African renaissance” that is necessary for the holistic implementation of the AU’s documented peacebuilding strategy.19 At a more theoretical level, what necessitated the development of the ASI in the overall agenda of the AU’s PCRD has both internal and external dimensions. From the internal perspective, there was a notion of African oneness and the indivisibility of African security, which reminded the AU member states of the pressing need to work together and showcase mutual solidarity in the PCRD for a stable Africa. From the external perspective, there was a realisation that extra-regional support was neither reliable nor sufficient to reconstruct and develop African societies that were coming out of violence. From both perspectives, it was a means to project African self-reliance and African ownership. It was not a mistake, therefore, that the initiative was launched under the motto “Africans helping Africa”.

The ASI is therefore not just an intra-African resource mobilisation instrument, but equally an African model on how to approach peacebuilding in a way that can yield expected results. It identifies some key strategies through which its overarching aim could be achieved. These include the deployment of advocacy and lobby missions on behalf of post-conflict African states for different strategic purposes; the organisation of African solidarity conferences (ASCs) to assemble varying resources for projects in post-conflict African states; the development of capacity-building programmes for institutional empowerment in post-conflict African states; convening experience-sharing workshops where post-conflict African states would have the opportunity to learn from the experiences of other African states; the deployment of expertise to post-conflict countries by other African states; and the organisation of investment forums for the purpose of facilitating the African private sector’s involvement in the AU’s PCRD undertakings. The responsibility of coordinating the implementation of the central dictates of the ASI was bestowed on the AUC. It was envisaged that the AUC would do this by developing a corresponding implementation roadmap, in consultation with relevant stakeholders such as the beneficiary states, RECs, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), among others. Following this mandate, a meeting was held in Johannesburg, South Africa, from 24 to 26 October 2012, to put in place a roadmap for the implementation of the scheme. The outcome of the meeting was adopted as the three-year roadmap for the execution of the ASI agenda.

In the last seven years, the AUC has attempted the implementation of the ASI by putting some of its ideas into practice. Two central achievements are noted. First, at the policy level, the ASI gained visibility as the AU’s flagship continental mechanism for mobilising diverse resources from within the African continent for rebuilding African countries that are emerging from violence. The 2016–2020 African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) reinforces the centrality of the ASI as the continental resource mobilisation instrument for AU peacebuilding undertakings in Africa. Second, at the implementation level, two ASCs have been organised so far. On 1 February 2014, the first ASC under the umbrella of the ASI was organised in Addis Ababa to mobilise needed resources for post-conflict states across the African continent. It drew participants from different African countries and partner international organisations, such as the AfDB, UNECA and so on. The second ASC was held on 1 February 2017, specifically to mobilise multifaceted support for the implementation of AU PCRD projects in the Central African Republic (CAR). These resource-raising conferences recorded only a very limited level of success, as the total financial donation traceable to the two instances is US$25 000, which was contributed by Liberia in 2017.20

The current reality shows that the ASI as an instrument for implementing the AU’s PCRD policy is gradually becoming an abandoned project. Besides the fact that the mechanism has not been effective in mobilising financial and in-kind resources for PCRD engagements in Africa, it is very hard today to find the continuing relevance of the scheme in the present AU’s peacebuilding enterprise. According to an AU policymaker, the “ASI has become a dead policy”.21 In fact, some of the AU’s ongoing intra-African solidarity actions on post-conflict reconstruction in countries such as The Gambia and South Sudan are carried out without any explicit reference to the ASI. A question that needs to be broached at this point is: what could have accounted for the atrophy of the initially celebrated ASI? Some of the key reasons that accounted for this development include the following. First, there is a problem of an “ambition-commitment gap”22 in the member states’ response to the ASI as a framework. There is no misgiving about the fact that the AU member states tend to have a shared ambition and conviction of the necessity for all African actors to collectively support post-conflict African countries to revamp and create an African continent that is peaceful, stable and developed. It was this very shared idea that propelled the process which eventually culminated in the creation of the ASI. Nonetheless, the actual commitment in this regard is either exiguous or not commensurable. This explains why pledges made by some member states during the 2014 ASC have still not been redeemed.23

Second, the AUC’s approach to the implementation of the ASI may have been problematic. The roadmap that was adopted for the three-year implementation of the mechanism was not comprehensive.24 It only identified what needed to be achieved in the first three years, and not how it would be achieved. The roadmap for implementation lacked details on specific strategies and processes. There also did not appear to have been follow-through on the roadmap. Even though it was recommended in the action plan, neither the ASI Secretariat nor the ASI Joint Steering Committee were created for the actualisation of the ASI. The three-year time frame for the roadmap elapsed in 2015 and no extended actionable plan was developed for the ASI, despite its recognition in the 2016–2020 APSA Roadmap as a subsisting instrument for the AU’s PCRD policy.

Third, there was a focus solely on the financial and state-centric aspects of the ASI, at the expense of other important parts of the initiative. It is therefore not surprising that the few documented efforts to operationalise the programme relied heavily on the utility of the ASCs, where the targeted resources were financial pledges and where the participants were mainly state actors. Invariably, other significant African actors such as the private sector, civil society organisations, academia, African experts, the diaspora and so on were rejected. In addition, other techniques – such as advocacy and lobbying missions, intra-African sharing of expertise, capacity-building programmes, tapping into existing bilateral technical cooperation schemes, investment forums and experience-sharing workshops – were also not given focus.

Fourth, for the past seven years, there was neither an active department coordinating actions under the ASI framework nor any implementation stakeholders that could engage different African actors and sectors at strategic levels for the robust implementation of the ASI. To this end, even though some of the AU’s recent resource mobilisation approaches for PCRD in Africa conveniently fall under the logic of the ASI programme, they were never executed through the ASI. For example, the pan-African deployment of experts to South Sudan and Gambia did not occur under the ASI.

Is it necessary to reinvigorate the African Solidarity Initiative?

The AU’s engagement in PCRD is a continuous, long-term process, as different African countries are still in their post-conflict phases. African policymakers have identified PCRD as one of the pathways to rekindle, renew and reengineer African growth and sustainable development. In this regard, is it necessary to reinvigorate the ASI as an instrument for implementing the AU’s PCRD policy? Answering this question is important for setting a policy direction for relevant AU organs and stakeholders in the context of their resource mobilisation strategies for post-conflict reconstruction in Africa. Three reasons stand out for the need to reorganise, re-energise and relaunch the ASI framework.

First, the reactivation of the ASI mechanism would strengthen African self-reliance in the AU’s PCRD activities and address the problem of overdependence on unpredictable international donors in African peacebuilding. It is worth noting that the underlying issues and challenges which led to the introduction of the ASI in 2012 are still very much relevant in the overall analysis of PCRD in Africa today. Because civil wars are always devastating and destructive to existing national structures, it is common knowledge that reconstruction for sustainable stability in post-conflict states consistently demands enormous resources and efforts. However, in the case of Africa, due to the combined factors of donor fatigue, preconditionality and inimical interests, resources coming from outside Africa are neither dependable nor sufficient to establish enduring peaceful coexistence in many post-conflict African countries.25 Siphamandla Zondi contends that “dependence on external financing of peacebuilding defeats the very purpose of the AU approach”.26 Reports from interdisciplinary missions that were deployed to different post-war African countries reveal that resource scarcity, in different forms, is central to the challenges confronting post-conflict stabilisation projects in Africa.27 At least for the next few years, resources contributed by international partners are never going to be sufficient for implementing the AU’s agenda in post-conflict peacebuilding. It is still in the collective interest of African stakeholders to jointly look inward for an effective, self-reliant resource mobilisation strategy that will prevent further conflict relapse. In the words of Claude Ake, “A vague belief in a common destiny, and the failure of certain imported Western institutions [and solutions] have predisposed Africans to look increasingly within the continent for the answers to their problems.”28 As such, the revival of the ASI is one of the surest ways to rekindle and institutionalise African self-reliance and ownership in the AU’s peacebuilding endeavours and for operationalising the shared idea of “African solutions to Africa’s problems”.29

Second, reviving the ASI is pivotal for institutionalising a unique African approach to PCRD that could hardly be offered externally. For so long, Western powers and their international agencies have somehow placed liberal democracy – and perhaps liberal economic reforms – at the heart of their approach to peacebuilding in post-conflict countries, particularly in the Global South.30 The acute implication of this is that they pay less attention to other key aspects of peacebuilding, such as intra-regional capacity-building, experience-sharing, investment and the participation of African private sector actors. These missing aspects are what the ASI can focus on in the AU’s PCRD engagement, by harnessing human and technical resources from within the African continent.

Third, the reinvigoration of the ASI framework is indispensable for consolidating, empowering, institutionalising and channelling age-long African solidarity norms for peacebuilding interventions in Africa. The practice of African solidarity and mutual assistance, even in the face of post-conflict realities, is key in the international relations between and among countries in Africa. However, the operationalisation of this solidarity norm is ad hoc, disjointed and uncoordinated, and therefore does not yield expected outcomes in terms of adequate resources mobilisation for African post-conflict reconstruction. The revival of the ASI framework would help to institutionalise coordination and synergy in African solidarity norms for more effective post-conflict peacebuilding in Africa. The robust implementation of the AU’s PCRD policy, in this case, requires the effective operationalisation of the ASI framework.31

Conclusion: Recommendations for the resuscitation of the African Solidarity Initiative

The usefulness of the ASI in the AU’s PCRD interventions in Africa is indispensable and cannot be overemphasised. Resuscitation of the ASI would re-engineer and strengthen the AU’s efforts in post-conflict peacebuilding in Africa. How, then, can the ASI be reactivated?

First, there must be a renewal of political engagement at strategic policy levels. The present key document containing the ASI ideas is, at best, a declarative statement, which is more a statement of intention and does not contain concrete steps to bring it to reality. There should be a purposeful policy framework designed, which contains details for implementation to become a clear action plan. This is important for at least three reasons. It would rekindle a new political commitment and buy-in at strategic levels across the relevant AU decision-making organs; articulate the ASI’s implementation modalities; and enunciate how it differs from, or relates to, the AU Peace Fund (PF).

Second, the means of generating financial resources for the ASI, particularly from the member states, should focus exclusively on the PF rather than the ASC, to avoid duplication of contributions. In this scenario, the means of funding the initiative through African-owned resources would be self-assuring, since African countries are increasingly demonstrating their commitments to the AU’s PF.32 This is not difficult to achieve, since the AU PSC, at its 593rd meeting on 26 April 2016, unequivocally asserted that a percentage of the PF would “be dedicated to support AU PCRD projects on the continent”.33

Third, there should be a focus on the mobilisation of in-kind resources, while depending on the PF as a key financial source. In-kind supports – which are not necessarily measured in monetary terms – are germane for sustainable peacebuilding processes. Effective mobilisation of in-kind resources through the ASI would invariably strengthen the AU’s interventions in post-conflict states. A clear way to facilitate this process is for AU policymakers to develop a strategy that would integrate existing pan-African bilateral cooperation into the ASI framework.

Fourth, African private sector actors must be engaged to participate and contribute to the ASI. For the past seven years, these actors have been largely neglected in the effort to implement the ASI. Many of these private sector actors, such as Mobile Telephone Networks (MTN), have the capacity to offer necessary contributions that are pivotal for peacebuilding interventions in Africa.

Fifth, there is no doubt that the newly established AU PCRD Centre has a central role to play if the ASI becomes an effective and functioning mechanism for intra-African resource mobilisation for peacebuilding interventions in Africa. The centre should be empowered as a platform for coordinating and implementing the ASI project in terms of advocacy, strategic engagement and reporting.

Finally, a group of ASI implementation stakeholders and advocates should be established. The membership of the group should include, among others, regular AU staff, peacebuilding policy experts and representatives of some member states. They should serve as the interface, while working very closely with the PCRD Centre in engaging different African constituencies in the implementation of the ASI.

The renascence of the ASI as a way of empowering African peacebuilding is not impossible. To achieve this goal, however, demands a new ASI implementation framework, activation of the PF as the ASI’s major financial source, and placing of more focus on in-kind resource mobilisation within the scheme. There is also a need for the participation of African private sector actors, coordinating the role of the AU PCRD Centre and the establishment of ASI implementation ambassadors. Taking these steps may be necessary for an African renaissance in the area of post-conflict peacebuilding. As Ali Mazrui asserted, “African hopes may… lie in other areas of organized self-reliance.”34

Endnotes

- This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship.

- For more information on the AU’s ambition for a conflict-free Africa, see Organisation of African Unity (OAU)/African Union (AU) (2013) 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration, 26 May.

- African Union (2015) African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) Roadmap 2016-2020. Addis Ababa: African Union Commission.

- African Union (2017) Third Progress Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the African Union’s Efforts on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development in Africa, PSC/PR/2.(DCLXX), 22 March.

- Murithi, Timothy (2005) The African Union: Pan-Africanism, Peacebuilding and Development. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing.

- “Silencing the Guns by 2020” is a policy agenda enunciated by the AU’s Assembly of Head of State and Government on 26 May 2013. It aims at ending all violent conflicts in Africa by the year 2020. For more information about this policy goal, see OAU/AU (2013) 50th Anniversary Solemn Declaration, 26May.

- African Union (2015) op. cit.

- African Union (2002) Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union. Addis Ababa: African Union Commission.

- African Union (2006) Policy on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD). Adopted in Banjul, Gambia.

- Lotze, Walter and De Coning, Cedric (2010) Looking Back when Looking Forward: Peacebuilding Policy Approaches and Processes in Africa. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 5 (2), p. 108.

- Personal interview, 17 September 2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. This further buttresses Zondi’s argument that the “AU sees peace as linked to development”. See Zondi, Siphamandla (2017) African Union Approaches to Peacebuilding: Efforts at Shifting the Continent towards Decolonial Peace. African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 17 (1), p. 123.

- For an account of some of the post-conflict African countries that experienced relapse in the second decade of the 21st century, see Khadiagala, Gilbert M. (2017) Whither Peacebuilding? A Reflection on Post-conflict African Experiences. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies – Multi-, Inter and Transdisciplinarity, 12 (1), pp. 91–106.

- All the multidisciplinary assessment missions that the AUC deployed to different post-conflict African states – such as Central African Republic (2006 and 2012), Sierra Leone (2009), Liberia (2009), Burundi (2010), Democratic Republic of the Congo (2010) and South Sudan (2011) – confirmed the prevailing problem of inadequate resourcing in post-conflict African states.

- African Union (n.d.) ‘Concept Note: African Solidarity Initiative in Support for Post-conflict Reconstruction and Development in Africa’, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/asi-concept-note.pdf> [Accessed 8 August 2019].

- Murithi, Timothy (2005) op. cit., p. 2.

- African Union (2012a) ‘Declaration on the Launch of the African Solidarity Initiative (ASI) for the Mobilization of Support for Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development in Africa’, Available at: <http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/asi-declaration-en.pdf> [Accessed 10 September 2018].

- Lucey, Amanda and Gida, Sibongile (2014) Enhancing South Africa’s Post-conflict Development Role in the African Union. Institute for Security Studies (ISS), Paper 256, May.

- African Union (2012a) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Personal Interview, 23 August 2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Personal interview, 17 September 2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- The concept of “ambition-commitment gap” resembles what Lucey and Gida describe as “over-committing and under-delivering”. Lucey, Amanda and Gida, Sibongile (2014) op. cit.

- For a detailed analysis of pledges made during this conference, see Bruce-Tetteh, Vivian (2014) Drafted Report on the African Solidarity Conference.

- African Union (2012b) Report on Workshop to Draft Roadmap for Implementation of the African Solidarity Initiative (ASI). Johannesburg, South Africa, 24–26 October.

- Englebert, Pierre and Tull, Denis M. (2008) Postconflict Reconstruction in Africa: Flawed Ideas about Failed States. International Security, (32) 4, pp. 106–139.

- See Zondi, Siphamandla (2017) op. cit., p. 125.

- African Union Peace and Security Council (AU PSC) (2006) Report of the Multidisciplinary Experts’ Mission to the Central African Republic (CAR), 3–15 April 2006. Addis Ababa: African Union; AU PSC (2009a) Report of the Multidisciplinary Team of Experts’ Mission to Liberia, 9–20 February 2009. Addis Ababa: African Union; AU PSC (2010a) Multidisciplinary Mission for Evaluation of Post-conflict Reconstruction and Development Needs in DRC (21 January–13 February 2010) and Burundi (13–22 February 2010), PSC/PR/2 (CCXXX). Addis Ababa: African Union; AU PSC (2010b) Communiqué, PSC/PR/COMM. (CCXXX). Addis Ababa: African Union; and AU PSD (2009b) Report of the Multidisciplinary Team of Experts’ Mission to Sierra Leone, 2–8 February 2009. Addis Ababa: African Union.

- Ake, Claude (1965) Pan-Africanism and African Governments. The Review of Politics, 27 (4), p. 539.

- Lucey, Amanda (2015) Implementing the Peace, Security and Development Nexus in Africa. Strategic Analysis, 39 (5), p. 507.

- Paris, Roland (2004) At War’s End: Building Peace after Civil Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- The points raised in this section reinforce the opinions and thoughts shared by a number of AU policymakers and practitioners during the author’s personal communication with them.

- Personal interview, 24 September 2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- AU PSC (2016), Communiqué, PSC/PR/COMM. (DXCIII), 26 April, Addis Ababa.

- Mazrui, Ali (1977) Africa’s International Relations: The Diplomacy of Dependency and Change. Colorado: Westview Press, p. 18.