Introduction

The United Nations (UN) Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) is one of the three pillars that integrates the known Peacebuilding Architecture (PBA), in conjunction with the Peacebuilding Commission (PBC) and the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO). The PBF was initially designed as a fund for post-conflict peacebuilding and since its inception in 2005, it has taken a proactive role in financing projects and programmes aiming at peacebuilding around the world. The PBF has engaged mostly in African countries, when compared to other recipient countries. This article analyses the role played by the PBF during its first decade of functioning (2005–2015).

What is the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund?

The PBF was originally conceived when the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) approved the resolutions establishing the PBC in December 2005.1 Initially, the PBF was designed to be a multiyear standing fund for post-conflict peacebuilding that would be funded by voluntary contributions, with a focus on “the immediate release of resources needed to launch peacebuilding activities and the availability of appropriate financing for recovery”,2 as well as supporting interventions that were considered critical to the peacebuilding process that directly contributed to the stabilisation of countries emerging from conflict.3 Although the PBF was conceptualised in 2005, it gained a formal structure only eight months after the adoption of the UNSC and UNGA’s decisions on the PBC. In August 2006, former UN Secretary-General (UNSG) Kofi Annan was requested to report to the UNGA on how the PBF should be designed. The document, entitled Arrangements for Establishing the Peacebuilding Fund, expressed not only the context in which the PBF emerged but also the funding gapit was filling – being the financial support to countries where no other funding mechanism was available.4 Most importantly, the document established the terms of reference (ToR) of the PBF. When formally launched, the ToR “indicate[d] that funding from the [PBF] will be informed by an analysis of critical gaps in peacebuilding that would be conducted by national authorities and the United Nations presence in the country concerned”.5

In this regard, the ToR became the PBF’s guidelines, since they delimitated the structure of the Fund as well as the role each actor should play within the financial mechanism for peacebuilding. In addition, the ToR determined that the PBF structure should be centralised with the UNSG, who determines country eligibility for the PBF, and also that the PBF should be managed by the PBSO and administered by the United Nations Development Programme – Multi Partner Trust Fund (UNDP-MPTF), which administers 181 funding mechanisms. The ToR determined that the PBF was created to be a mechanism focused on four specific areas:

- activities in support of the implementation of peace agreements;

- activities in support of efforts by the country to build and strengthen capacities that promote coexistence and the peaceful resolution of conflict;

- establishment or re-establishment of essential administrative services, which may include the payment of civil service salaries and other recurrent costs; and

- critical interventions designed to respond to imminent threats to the peacebuilding process, such as the reintegration of ex-combatants disarmed under a disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programme.6

In pragmatic terms, these four areas are what the PBF envisions for peacebuilding. These strategies refer to a filtering process for determining what must be financed with regard to which country becomes eligible for funding. This means that in its scope, the PBF has direct engagement at the country level through two axes of financial support: the Immediate Response Facility (IRF), which is designed for “wherever peacebuilding opportunities arise in the immediate aftermath of political crisis or conflict”,7 and the Peacebuilding Response Facility (PRF), which is “typically applied within several years following the end of a conflict to support national efforts and consolidate peacebuilding”.8 Both the IRF and PRF were designed as part of the process of making the PBF catalytic and responsible for the respective contexts of the countries’ need.

Context

The creation of the PBF was part of an institutional discourse within the UN that there was no platform capable of providing peacebuilding recovery to countries in their transitional phase from war to peace,9 and that the new architecture was a way the UN found for not taking “its eyes off countries emerging from conflict too soon”.10 Although this perception was a central argument for the emergence of the Peacebuilding Commission, with regard to the PBF, there are three main features. First, it “was established to reduce the propensity of countries relapsing into violent conflict as a result of faltering peacebuilding processes due to the absence of sufficient funds to run projects”.11 Second, it was “intended to help kick-start peacebuilding activities in war-torn countries at an early stage” – indicating that the PBC would have little financial clout due to the size of the PBF structure.12 And third, it was “designed to provide catalytic funding to reinforce financial assistance by other agencies”.13 When the PBF was formally created, it was a fund for post-conflict countries, and not for providing financial support only to countries included in the PBC. This enabled it to play an important role in the financing peacebuilding niche. In this regard, the PBF became the PBA’s fund for peacebuilding.

Table 1: African Countries that Benefited from the PBF (2007–2015)14

| Burundi |

| Central African Republic |

| Chad |

| Comoros |

| Côte d’Ivoire |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Guinea |

| Guinea-Bissau |

| Kenya |

| Liberia |

| Libya |

| Madagascar |

| Mali |

| Niger |

| Sierra Leone |

| Somalia |

| South Sudan |

| Sudan |

| Uganda |

Although this analysis refers to the first decade of the PBF (2005–2015), the official data from the PBF support dates from 2007, which implies data compilation of nine years only. Within this time frame, the PBF provided financial support to 33 countries.15 Geographically, the majority of these recipient countries were located in Africa, with 19 countries, as Table 1 depicts. Other countries were located in Asia (seven), Central and South Americas (three), Middle East (two), Europe (one) and Oceania (one). There was a prevalence for financing peacebuilding in Africa due to the fact that when the UN decided to establish the PBC, its focus was exclusively on African countries.16This influenced where the PBA could provide its role. This perception has support in what scholars explained about the role of the PBA in Africa. For some, the UN has a long and impressive history of engaging in Africa through peacebuilding, symbolised by supporting decolonisation processes and also by the role of peacekeeping operations on the ground,17 making Africa “the site of a large number of international and continental projects to promote peace”.18 In addition, the focus on Africa implied that PBF funding played a role in legitimising peacebuilding projects and programmes in the respective African countries, and in enhancing an agenda for reconstruction.

PBF’s Agenda for Peacebuilding

Table 2: Number of PBF Projects per Continent (2005–2015)19

| Africa | 300 |

| Asia | 50 |

| Middle East | 16 |

| Central/South Americas | 8 |

| Oceania | 7 |

| Europe | 1 |

| Total number of projects | 382 |

The majority of African countries that benefited from the PBF had a direct implication on the number of peacebuilding projects and programmes financed by the Fund. Looking at the quantity of projects when compared from a continental perspective, the PBF provided financial support to 382 projects and programmes around the world during its first decade. These projects were approved for starting implementation until the end of 2015. From this total, only African countries20 were responsible for the allocation of financial support to 300 projects, as Table 2 shows. Africa had the highest number of projects implemented under the PBF, followed by Asia, Middle East, Central and South Americas, Oceania and Europe.

This active role enabled the PBF to become the UN fund for post-conflict peacebuilding, with the “unique role of providing funding for strategic peacebuilding plans through country-based steering committees that resemble the role played by country-level MDTFs [multi-donor trust funds]”.21 This role was made possible because the PBF found its potential niche, where it could fill a gap among the increased number of MDTFs “driven to some extent by donors who wanted to support selected themes in a more visible manner, as distinct from providing financial support for agency programs”.22 Based on the idea that it “was important for the PBF to have clearly defined funding priorities while allowing for some flexibility in activities that could be supported in a specific transition context”,23 the quantity of projects financed reveals more than a number – rather, the PBF’s direction on what it intended to be peacebuilding in practice. The agenda that the PBF financed as part of a broader institutional practice designed exclusively for post-conflict settings, comprising the implementation of a range of programmes across many thematic areas,24 is good reference. All PBF recipient countries implemented projects under six main thematic areas: Democratic Governance, Security, Youth Empowerment/Employment, Public Administration, Human Rights, and National Political Dialogue. As Africa led the quantity of projects financed by the PBF, the implementation of the 300 projects was focused exclusively on four main areas of intervention: Democratic Governance, Security, Youth Empowerment/Employment, and Public Administration.

Table 3: Number of PBF Projects per Thematic Area in Africa (2005–2015)25

| Democratic Governance | 66 |

| Security | 45 |

| Youth Empowerment/Employment | 32 |

| Public Administration | 30 |

| Human Rights | 9 |

| National Political Dialogue | 6 |

| Energy Power | 1 |

| Property and Land | 2 |

| Community Affected by Conflict | 13 |

| PBF Unallocated | 4 |

| PBF-IRF | 92 |

| Total | 300 |

The panorama of what the PBF financed in Africa reflects that projects within the scope of Human Rights and National Political Dialogue were less than what should be expected, assuming the notion that peacebuilding does not only comprise strategies aimed at structural change on state-centric behaviour. In addition, the data highlighted in blue in Table 3 represents areas limited to specific26 demands only, which did not become a common agenda for some African countries.27 The PBF also concentrated part of its funding on emergency needs under the IRF, in which 92 projects – highlighted in red in Table 3 – focused on rapid funding within the time frame of up to 18 months. This funding was divided, based on two amounts: up to US$3 million when there was no eligibility required and the decision relied on the PBSO,28 and up to US$15 million when the UNSG decided which country was eligible for funding from the PBF.29

Implications for Peacebuilding in Africa

Designing a peacebuilding framework embedded in the identified thematic areas corroborates with what Curtis30 has elucidated in understanding peacebuilding. There are three main ideas on which the debate on peacebuilding, with a focus on Africa, should be considered: peacebuilding as part of a liberal agenda, a strategy for stabilisation, and a structure for achieving social justice.Despite the fact that these ideas “rest on different conceptions of power and politics in Africa”,31 one does not neglect the other. Rather, they congregate “important normative assumptions about the nature of peace”.32 Since peacebuilding as social justice represents the diffusion of an international and institutional agenda, such diffusion implies that these PBF countries in Africa were prone to behave as if they were on the road to peace. Such a perspective on behavioural change reflects what Kühn33 pointed out on this issue, affirming that peace becomes an institutional exercise, being understood more as a policy rather than as a vague concept.

Table 4: Amount of financial support from the PBF per continent (2005–2015)34

| Africa | US$498 872 810.00 |

| Asia | US$70 808 985.00 |

| Middle East | US$23 712 026.00 |

| Central/South Americas | US$16 799 999.00 |

| Oceania | US$9 090 836.00 |

| Europe | US$2 000 000.00 |

| Total | US$621 284 656.00 |

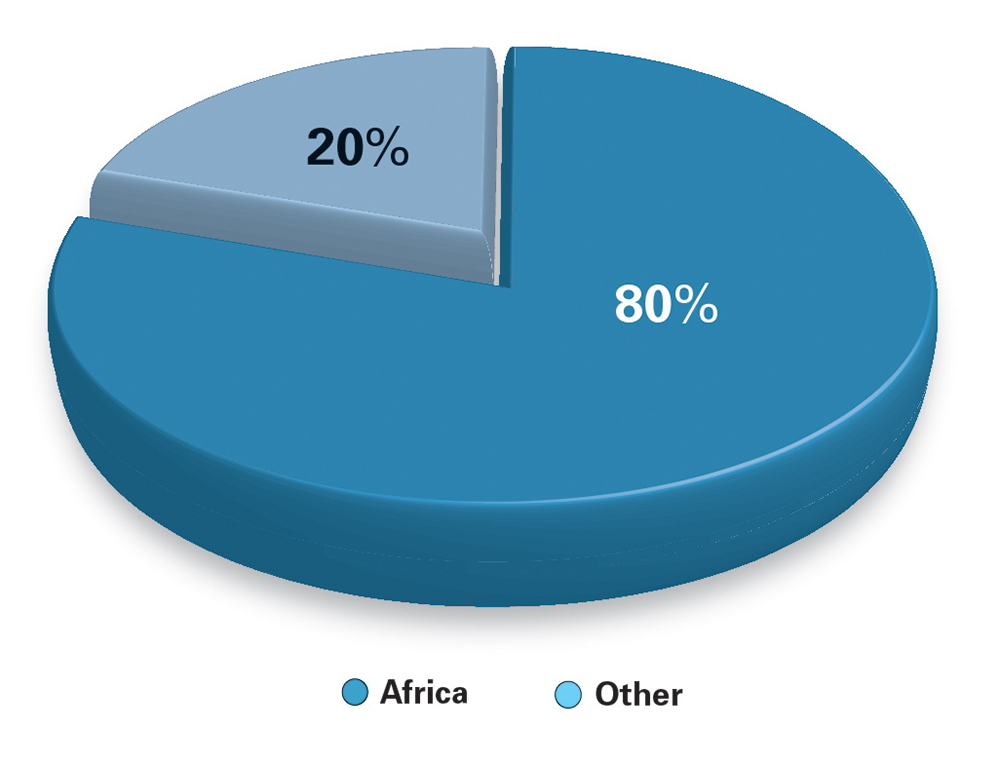

Africa is the main continent where the PBF played a role, mainly with regard to the quantity of projects financed, the common agenda and the amount of money donated to these respective projects. As Table 4 shows, the amount of money donated for peacebuilding projects in African countries is four times higher than that allocated to the other continents combined. Africa leads with 80% of funding from the PBF during this first decade of analysis, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: PBF Funding Comparison

Such evidence does not mean that the PBF had a preference for investing in African countries, rather that African countries seized the opportunities opened by the PBF while also bringing to the UN what the challenges were for peacebuilding from the ground, and what the promotion of peacebuilding posited to them and to the organisation.

This perspective is embedded in the notion that peacebuilding is the “associative approach”, in which its “structures must be found [to] remove causes of wars and [to] offer alternatives to war in situations where wars might occur”.35 Within this conceptualisation, peace “must be built within nations as well as between nations”.36 As such, peacebuilding does not only acquire a connotation of being associated with countries facing transitional phases from intrastate war to peace but, most importantly, it becomes incorporated into a multilevel approach in which peacebuilding is an inherent part of the local, national, institutional and international practice of politics.

Final Considerations

Although the PBF was established by the UN as part of the creation of the PBC, it acquired an active role in financing peacebuilding projects and programmes around the world. The concentration of money allocated to African countries does not mean that the PBF had a country bias for justifying what must be financed, but that each country posited different perspectives of what peacebuilding is and how the combined demands reflect the challenges of peacebuilding.

Endnotes

- United Nations Security Council (2005) ‘Resolution 1645 (2005) Adopted by the Security Council at its 5335th meeting, on 20 December 2005’, S/RES/1645(2005), Available at: <https://undocs.org/S/RES/1645(2005)> [Accessed 1 February 2020].

- Ibid.

- United Nations General Assembly (2006) ‘Arrangements for Establishing the Peacebuilding Fund. Report of the Secretary-General’, A/60/984, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/A/60/984> [Accessed 1 February 2020].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO) (2014) ‘United Nations Peacebuilding Fund (PBF). Guidelines on Application and Use of Funds’, Available at: <www.un.org/peacebuilding/fund/documents/guidelines> [Accessed 20 August 2016].

- Ibid.

- United Nations General Assembly (2005) ‘In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All. Report of the Secretary-General’, A/59/2005, Available at: <https://undocs.org/en/A/59/2005> [Accessed 1 February 2020].

- De Coning, Cedric and Stammes, Eli (2016) Assessing the Impact of the UN Peacebuilding Architecture. In De Coning, Cedric and Stamnes, Eli (eds) UN Peacebuilding Architecture: The First 10 Years. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–20.

- Murithi, Tim (2008) Peacebuilding or ‘UN-Building’? African Institutional Responses to the Peacebuilding Commission. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, 4 (2), pp. 89–94.

- Miall, Hugh (2007) The EU and the Peacebuilding Commission. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 20 (1), pp. 29–45.

- Otobo, Ejeviome Eloho (2015) Consolidating Peace in Africa: The Role of the United Nations Peacebuilding Commission. Princeton: AMVPS.

- United Nations Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office (MPTF-O) (2016) ‘Trust Fund Factsheet – Peacebuilding Fund’, Available at: <http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/PB000> [Accessed 31 January 2020].

- Ibid.

- From the first decade (2005–2015) of the functioning of the PBC, only six countries were included in its agenda: Burundi, Central African Republic, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia and Sierra Leone. See also Murithi, Tim (2009) The Ethics of Peacebuilding. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Otobo, Ejeviome Eloho (2015) op. cit.

- Curtis, Devon (2012) The Contested Politics of Peacebuilding in Africa. In Curtis, Devon and Dzinesa, Gwinyayi A. (eds) Peacebuilding, Power, and Politics in Africa. Ohio: Ohio University Press, pp. 1–28.

- MPTF-O (2016) op. cit.

- Based on the UNDP-MPTF Gateway, projects and programmes financed by the PBF are classified as Operationally Closed, Financially Closed or On Going.

- Lotz, Christian (2011) Financing for Peacebuilding: The Case for a Broader Concept of Aid Effectiveness. Journal of Peacebuilding and Development, 6 (2), pp. 1–14.

- Williams, Abiodun and Baily, Mark (2016) The Vision and Thinking Behind the UN Peacebuilding Architecture. In De Coning, Cedric and Stamnes, Eli (eds) op. cit., pp. 23–39.

- Ibid.

- Jenkins, Rob (2013) Peacebuilding: From Concept to Commission. New York: Routledge.

- MPTF-O (2016) op. cit.

- The project under the theme “Energy and Power” was implemented only in Sierra Leone, and the one identified as “Community Affected by Conflict” was implemented in the Central African Republic exclusively. Projects under the theme “Property and Land” were implemented in Burundi and Liberia.

- “Unallocated” refers to projects financially supported by the PBF in which there is no specific theme identified. The four projects identified as “unallocated” were implemented in Sierra Leone only. See: MPTF-O (2016) op. cit.

- MPTF-O (2016) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Curtis, Devon (2012) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kühn, Florian P. (2016) International Peace Practice: Ambiguity, Contradictions and Perpetual Violence. In Turner, Mandy and Kühn, Florian P (eds) The Politics of International Intervention: The Tyranny of Peace. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 21–38.

- See endnote 16.

- Galtung, Johan (1976) Three Approaches to Peace: Peacekeeping, Peacemaking and Peacebuilding. In Peace, War and Defense: Essays in Peace Research, Vol. 2. Copenhagen: Ejlers, pp. 282–304.

- Ibid.