Introduction

This article is an attempt to interrogate Zimbabwe’s national unity and reconciliation efforts through one of its key organs, the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC). It contends that while the NPRC potentially represents a first attempt at resolving Zimbabwe’s violent past, the central premise on which both the Commission and the government’s broader national unity and reconciliation policy are based is critically flawed. The unity that the government seeks to achieve as a vehicle for reconciliation relies upon a negation of accountability, itself a core component of national healing and reconciliation that allows for an open and honest engagement with Zimbabwe’s dark and gruesome past. The problem is further compounded by what has been seen by many as the government’s unwillingness to engage honestly and genuinely with the past, possibly because a good number of past and current serving senior government officials fear implication.

The article also highlights some of the complexities that continue to characterise the national mood as far as national healing and reconciliation is concerned. For example, proposals were made recently at an Exchange Seminar of Civic Society Organisations (CSOs) in Bulawayo to have the NPRC’s mandate stretch from as far back as the 11th century. How to address all these issues holistically, given the limited time the Commission has before its official expiry, is something the Commission must be innovative about. These challenges demonstrate the mammoth task the NPRC has, and the responsibility it shoulders.

Reconciliatory Efforts: Retributive or Restorative Justice, or Both?

In the context of Zimbabwe and the NPRC model, restorative justice can be defined as a process aimed at the redefinition of crime so that is it seen not as an offence against a “faceless state”, but as wrongs or injuries done to other persons. Restorative justice, by its nature, seeks to promote healing and reconciliation of all concerned parties – victims in the first place, but also offenders, their families and the larger community. At the heart of restorative justice is the recognition that both victim and offender must be directly involved in the resolution of conflict.

A retributive model of justice, on the extreme end, is concerned with a prosecutorial approach as a means to “restoring” justice. Both models have their advantages and disadvantages. Finding what works best under which conditions is critical for successful post-conflict reconstruction and peacebuilding.

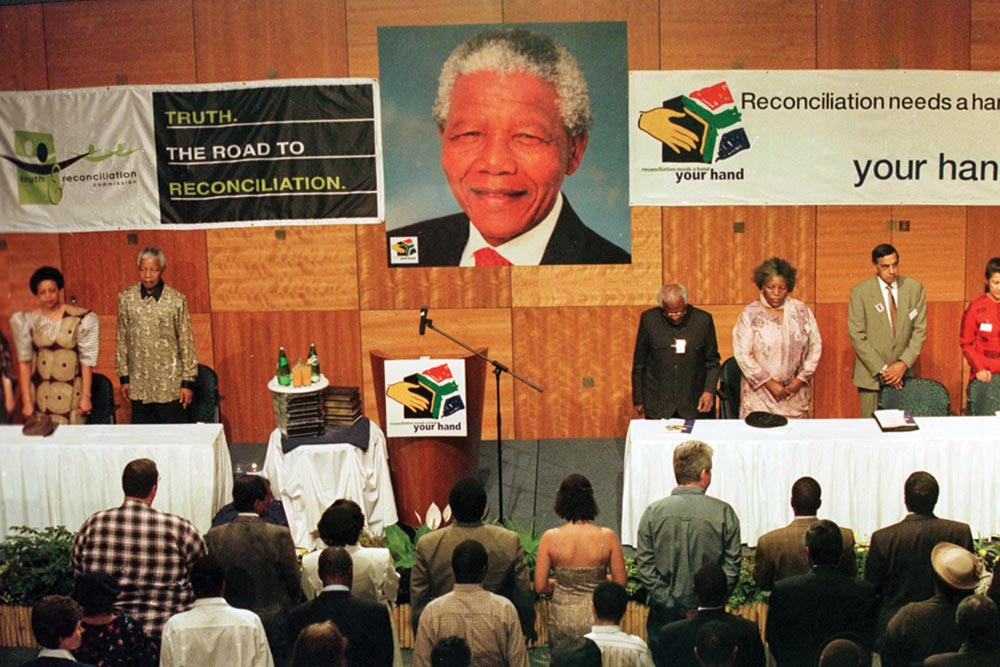

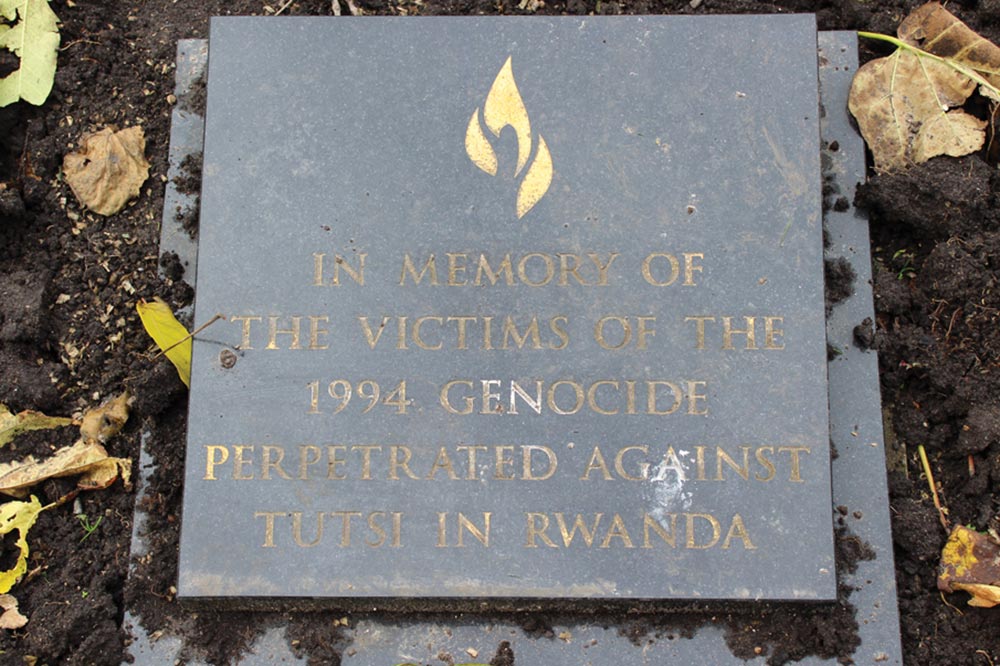

In post-conflict societies such as Zimbabwe where mass atrocities, violence and human rights violations have occurred, the following questions are key: Are healing and reconciliation possible? If so, how can they be achieved and if not, what are the consequences? Literature on transitional justice has traditionally focused on two particular mechanisms that are believed to aid reconciliation processes significantly.1 These are truth and reconciliation commissions (TRCs) and criminal trials. The former, in the case of South Africa, played a fundamental role in establishing the truth of what happened – a key prerequisite for reconciliation – while criminal trials reputedly facilitate reconciliation largely through dispensing justice. Post-genocide Rwanda is a case in point. There is currently a huge debate in Zimbabwe – albeit in hushed voices – as to which approach could possibly lead to more positive and sustainable peace. Insights on what could possibly work for Zimbabwe are shared later in this article.

Healing and reconciliation efforts in Zimbabwe continue to face substantial challenges. Before 1980, Zimbabwe waged a protracted liberation struggle against the white settler government of Ian Smith. About 80 000 Africans are estimated to have died during this war, while a further 450 000 suffered injuries of varying intensities.2 Emerging from this dark past, it did not take long before the country was once again plunged into conflict – but this time it was ethnic strife, where more than 20 000 predominantly Ndebele-speaking people and Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) supporters were murdered between 1982 and 1987.3 Hostilities were eventually halted with the signing of the Unity Accord in 1987 between the leader of ZAPU and the leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). However, this “unity pact” has incurred heavy criticism for having been too elitist and not taking into consideration the voices of actual sufferers and victims. The complexities around what transpired during this period have been made worse by half-truths and an almost-persistent blame game by both parties. This phase, the “darkest” of all post-independence atrocities, has posed significant challenges for any efforts directed at national healing and reconciliation. Still coming to terms with that legacy of brutal violence, the country once again found itself plunged into a series of high-level conflicts– the violent seizure of white-owned farms in 2000 and Operation Restore Order in 2005, which was an operation disguised as a “war on filth” that is estimated to have displaced close to 700 000 poor urbanites.4 Less than three years after Operation Murambatsvina (“Clean the filth”), the country was engulfed in a violent electoral conflict in 2008. This conflict claimed scores of opposition supporters who were either, killed, maimed or raped in the ensuing political conflict following Robert Mugabe and the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front’s (ZANU-PF) defeat by Morgan Tsvangirai’s Movement for Democratic Change (MDC-T).

Unlike Rwanda – which chose to deal with its dark past by using a variety of approaches such as international trials at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), national trials in local courts of laws and, in some instances, traditional dispute resolution mechanisms (gacaca trials) – the Government of Zimbabwe adopted a policy of national unity and reconciliation through the NPRC, which came into operation under Section 251 of its newly adopted constitution. Under the Constitution of Zimbabwe, the NPRC will have a life span of 10 years, which started in August 2013. The Commission faced several challenges from its inception, which further delayed its effective start date. As an example, the eight commissioners were only sworn in on 24 February 2016, and not much work was done until 5 January 2018 when President Emmerson Mnangagwa signed the NPRC Bill into law, making operational the Commission that was appointed two years previously. The unnecessary delays in operationalising the Commission cut the life span of the NPRC by half. In recognition of the unnecessary delays on the work of the NPRC, there have been calls by some sections of civic society to have the NPRC’s full 10-year mandate reinstalled. Whether the government will relent is yet to be seen. Section 252 of the Constitution mandates the NPRC to do the following, among other functions:

- ensure post-conflict justice, healing and reconciliation;

- develop and implement programmes to provide natural healing, unity and cohesion and the peaceful restoration/resolution of disputes;

- encourage people to tell the “truth” about the past and facilitate the making of amends and the provision of justice;

- develop procedures and institutions to facilitate dialogue between political parties, communities and other groups; and

- take appropriate action on complaints received from the public.

From the functions outlined above, it is clear that the NPRC’s emphasis is not only on healing and justice as paths to reconciliation. Most importantly, it emphasises unity and cohesion as fundamental ingredients to healing and reconciliation. The inward-looking nature of the NPRC and its strong focus on the grassroots reflects a more holistic and comprehensive approach to reconciliation than conventional TRC approaches. Yet, the central premise upon which both the Commission and the government’s broader national unity and reconciliation policy are based is critically flawed and cannot be a vehicle for attaining positive and sustainable peace. In other words, the NPRC seeks to achieve national healing and reconciliation through the creation of a false unity that ignores the critical aspect of truth-telling and accountability, and hence, does not allow for an open and honest engagement with the past. A recent survey by Heal Zimbabwe Trust in Matabeleland North province, home to scores of victims of state violence, revealed that 36.7% of its respondents mentioned that they wanted to see the NPRC promote accountability, transparency and truth-telling first.5 Failure to deal with the past in a holistic and comprehensive manner leaves room for the past to rear its ugly head in the future.

Possibly, it may be argued that similar to Rwanda, the establishment of the NPRC reflects a critical recognition by the Government of Zimbabwe that criminal justice and trials alone (retributive justice) are not sufficient to bring about reconciliation, as opposed to restorative justice. Certainly, there is merit in this argument, but it also begs the question: How can justice be restored and reconciliation achieved when perpetrators of some of the most heinous crimes continue to live lavishly and get “rewarded” with top positions in government, while victims of violence continue to live in abject poverty and misery? Furthermore, none of the known perpetrators have taken responsibility for their past actions, nor issued public apologies in acknowledgement of their wrongdoing. These and other contentious issues beg the question: Is Zimbabwe’s NPRC an attempt at “reconciliation without justice”?6 These are critical questions that the NPRC and the Government of Zimbabwe need to interrogate seriously, given that securing restorative and socio-economic justice consequently become a broader basis for ensuring sustainable peace, healing and integration.

Despite the shortcomings of the policy, one could think that the NPRC potentially represents a significant and innovative model that could be adapted to other post-conflict societies to aid peacebuilding processes. First, as clearly outlined in its constitutional mandate, the NPRC has a broad and comprehensive mandate. This is important, given that reconciliatory efforts usually require holistic and multidimensional approaches to nation-building and peacebuilding. This contrasts favourably with TRCs – which, due to limited time, sometimes scarce resources and the magnitude of their task, “have to be selective in what they cover and emphasize”.7 Post-genocide Rwanda’s experience is a case in point. Second, and most importantly, is that societies and communities affected by large-scale violence of the magnitude of Gukurahundi, Operation Restore Order (Murambatsvina), land seizures (Jambanja) and the election violence of June 2008 need to own the reconciliation process. This is something that cannot be imposed from outside or in a top-down approach. Huyse notes that “lasting reconciliation must be home-grown” – because, in the end, it is the survivors who assign meaning to the terms and the processes.8 What is creative about the model adopted by the NPRC is that it transfers ownership of the reconciliation process to local communities and encourages them to become the primary actors. For example, one of the Commission’s key functions is to “develop procedures and institutions to facilitate dialogue between communities, political parties and other groups”.9 Finally, whereas TRCs (and, to some extent, war crimes tribunals) are essentially premised on the notion that truth is healing and represents a path to reconciliation, the NPRC seeks to create reconciliation primarily via unity and cohesion. Amadume correctly argues that it amounts to modern arrogance to assume that courts of law can be instruments of true healing and reconciliation.10

The Way Forward?

While few authors agree on what constitutes reconciliation or how to achieve it, two core elements can be identified. First and foremost, reconciliation entails the repair and restoration of relationships – and, regrettably, Zimbabwe has scored marginally on this. This explains why Zimbabwe continues to be plunged into conflicts, mainly of a political nature. Second, reconciliation involves dealing with the past, taking responsibility and acknowledging wrongdoing. In fact, Jeong notes: “As a critical first step, guilt needs to be recognised with the acceptance of responsibility for atrocities or other events symbolising intercommunal and interpersonal relations.”11 In this area, however, there has been minimal progress, with much playing of the “blame game”. On the one hand, it may be argued that the NPRC represents the first major attempt by Zimbabweans to confront their painful past and build a brighter and more prosperous future for all citizens. Yet, on the other hand, its attempts to forge national unity and reconciliation through the suppression of truth and constant denial and victim blaming on the part of perpetrators represents a serious flaw by both the government and the NPRC to engage honestly and genuinely with the past. In terms of Zimbabwe’s future, there are grounds for both optimism and caution. The NPRC, which represents an original concept born out of a compromise between various political parties and which demonstrates the first attempt post-1980 to engage the past honestly and truthfully, raises much optimism and has a critical role to play and a significant contribution to make to the peace process. At the same time, however, the NPRC is the manifestation of a fundamentally flawed approach that must be addressed.

The creation of unity and national cohesion must first embrace and acknowledge the truth about what happened, rather than deny it. Simply put, the NPRC must work with existing reality rather than trying to create a new reality of its own. The NPRC must also be seen to be independent in carrying out its activities rather than to be seen as pursuing an ulterior motive, which is likely to jeopardise the peace process in Zimbabwe. The NPRC has already started on a bad footing, with two of its public meetings in Bulawayo and Lupane disrupted by activists who felt the Commission was trying to shield “powerful” people from taking responsibility for the Gukurahundi atrocities committed in the aftermath of political independence. This is one of the challenges the NPRC might want to look into in the future. Similar disturbances occurred in Harare at a Southern African Political Economy Series (SAPES) policy discussion, aimed at creating dialogue on national healing and reconciliation in Zimbabwe. Perhaps an even bigger challenge for the NPRC and its overall objective of healing and reconciliation lies in Section 10 of the NPRC Act. In what is seen by many as a huge drawback, the Act empowers the Minister of National Security to block an investigation by issuing a certificate blocking disclosure of evidence and documentation that they may deem to be prejudicial to the defence, external relations, internal security or economic interests of the state. Such a provision undermines the work of the NPRC and its quest to achieve unity and national cohesion.

Conclusion

The NPRC marks the first and important positive step by the people of Zimbabwe to non-violently and peacefully confront a painful past of violence, socio-economic hopelessness, forced disappearances and gruesome murders. It is a constitutional mandate that the NPRC will have to handle with great agility and must demonstrate great skill in balancing and moderating different demands and expectations from the populace on one hand and the government on the other, to whom the Commission is accountable. The possibility of successful reconciliation, national healing and integration in Zimbabwe hinges on identifying those cultural elements that make us all human – for example, ubuntu/hunhu: “l am because you are” – loosely translated as “a person is a person through other persons”. Once these elements have been identified, they can be used to aid the process of healing and reconciliation. In other words, any attempts at reconciliation and healing that fall outside the purview of conflict resolution rooted in Zimbabweans’ rich cultural heritage are likely to fail. The values and philosophical concept of ubuntu/hunhu recognises and affirms the people of Zimbabwe’s common and shared existence, which creates an atmosphere conducive to honestly and truthfully engaging the country’s dark past with a view to promoting national unity and cohesion. Some of the fundamental values of ubuntu/hunhu are espoused in part of a reconciliatory speech that former president Mugabe gave on the eve of independence in 1980, according to De Waal:12

You and I must strive to adapt ourselves, intellectually and spiritually to the reality of our political change and relate to each other as brothers bound one to another by a bond of national comradeship. If yesterday I fought you as an enemy, today you have become a friend and ally with the same national interest, loyalty, rights and duties as myself. If yesterday you hated me, today you cannot avoid the love that binds you to me and me to you. Is it not folly, therefore, that in these circumstances anybody should seek to revive the wounds and grievances of the past? The wrongs of the past must now stand forgiven but must not be forgotten. If ever we look to the past, let us do so for the lesson the past has taught us, namely that oppression and racism are inequalities that must never find scope in our political and social system.

Endnotes

- Oomen, Barbara (2005) Donor-driven Justice and its Discontents: The Case of Rwanda. Development and Change, 36 (5), pp. 887–910.

- Hapanyengwi-Chemhuru, Oswell (2013) ‘Reconciliation, Conciliation, Integration and National Healing Possibilities and Challenges in Zimbabwe’, African Journal on Conflict Resolution, 2013/1, Available at: https://accord.org.za/ajcr-issues/reconciliation-conciliation-integration-and-national-healing/ [Accessed 5 April 2018].

- Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace (CCJP) (1997) Report on the 1980s disturbance in Matabeleland and the Midlands.

- Potts, Deborah (2006) ‘Restoring Order’? Operation Murambatsvina and the Urban Crisis in Zimbabwe. Journal of Southern African Studies, 32 (2), pp. 273–291.

- Heal Zimbabwe Trust (2018) ‘Pathways to Peace and Reconciliation: Literature Lessons for Zimbabwe’, Available at: <http://www.healzimbabwetrust.org> [Accessed 9 June 2018].

- Mawondo, Simon Zvinaiye (2009) ‘In Search of Social Justice: Reconciliation and the Land Question in Zimbabwe’, Available at: <http://www.crvp.org> [Accessed 31 March 2018].

- Chapman, A. (2009) Truth Finding in the Transitional Justice Process. In Van der Merwe, H., Baxter, V. and Chapman, A. Assessing the Impact of Transitional Justice: Challenges for Empirical Research. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, pp. 91–113.

- Huyse, Lucien; Bloomfield, David and Barnes, Terri (2003) Reconciliation After Violent Conflict: A Handbook. Stockholm: International IDEA.

- The National Transition Justice Working Group of Zimbabwe (NTJWZ) (2017) A Guide to Understanding the National Peace and Reconciliation Commission in Zimbabwe.

- Amadiume, Ifi (2000) The Politics of Memory: Biafra and Intellectual Responsibility. In Amadiume, Ifi and An-Na’im, Abdullahi A. (eds) The Politics of Memory: Truth, Healing and Social Justice. London, New York: Zed Books, pp. 38–55.

- Jeong, Ho-Won (2005) Peacebuilding in Post-conflict Societies: Strategy and Process. Boulder, Co: Lynne Rienner.

- De Waal, Victor (1990) The Politics of Reconciliation: Zimbabwe’s First Decade. London: Hurst and Company.