Introduction

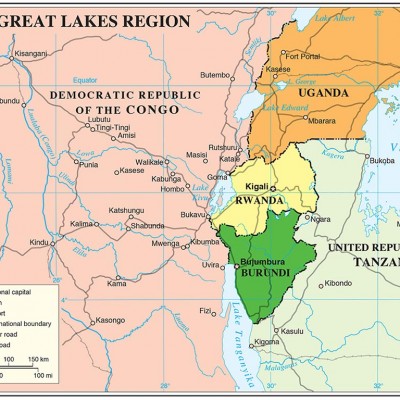

In today’s violent conflicts, civilians are increasingly caught on the frontline. Africa’s Great Lakes Region has witnessed some of the most intense violence and protracted conflict of the last half-century. The region is home to some of Africa’s most intractable and turbulent conflicts, reflected by the genocide in Rwanda, civil war in Burundi and South Sudan, conflict in Sudan (Darfur), cross-border conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), exacerbated by internal and external illegal armed groups; and, more recently, sectarian conflict in Central African Republic (CAR). One of the most devastating forms of extreme hostility waged against civilians in the region is conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV). While women and girls are often the primary targets, CRSV is also strategically perpetrated against men and boys. Even with all the measures put in place in the region and in CAR, recent and fresh allegations against peacekeepers continually surface. The circumstances that render women and children vulnerable to these situations include low economic empowerment and displacement due to conflict, leading to a lack of food, security and shelter. For some women and children, this may lead to transactional sex in exchange for these basic needs, while others are coerced or sexually violated by armed groups or security forces. Sexual violence, exploitation and abuse impacts on the social fabric of society and hinders effective post-conflict reconstruction.

This article draws from the experiences of CAR and discusses the lessons learned regarding sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) as a result of conflict in the country.

Conflict in CAR, the Plight of Civilians and a Peacekeeping Mandate to Protect Civilians

In December 2013, the mainly Christian anti-Balaka (anti-machete) movement took up arms against the mainly Muslim Séléka rebel coalition which had staged attacks in the country, leading to intercommunal clashes. The conflict also took on increasingly sectarian overtones. Months of violence led to wrecked state institutions, leaving millions on the brink of starvation. Thousands of people are believed to have been killed, and 2.5 million people – more than half of the entire population – needed humanitarian aid.1 Widespread human rights violations were reported during this period. Following the continued escalation of the conflict, the United Nations (UN) Security Council authorised an African Union (AU)-led International Support Mission to the CAR (MISCA) and a French-backed peacekeeping force (known as Operation Sangaris) through its Resolution 2127 (2013), to quell the spiralling violence. MISCA transitioned to the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in the CAR (MINUSCA) in 2014, due to the security requirements on the ground that called for a bigger force. MINUSCA is mandated to protect civilians and undertake the promotion and protection of human rights in CAR, among other key tasks. The conflict in CAR has increased the vulnerability of its civilians to CRSV, including SEA.

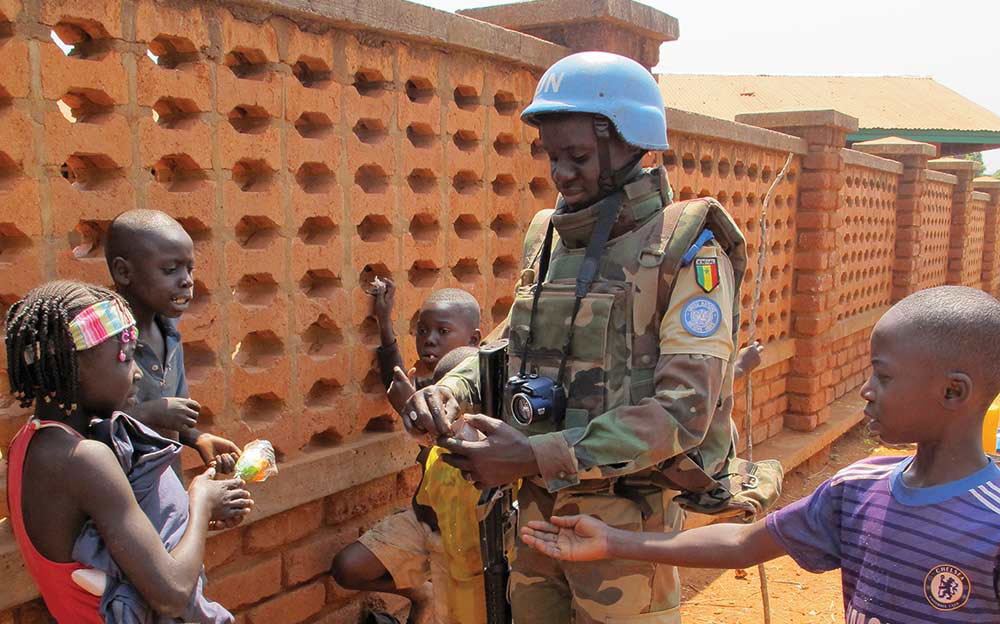

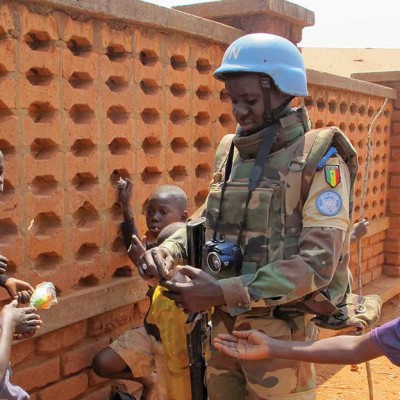

CAR is currently home to peacekeepers from all over the world, among them UN peacekeepers and European troops (authorised by the UN Security Council). The Great Lakes Region contributes 40.6%2 of all the uniformed peacekeepers in MINUSCA. Some UN peacekeepers in CAR – from Bangladesh, the DRC, Morocco, Niger and Senegal – have been implicated by the allegations of SEA. Troops from Europe have also been named in recent SEA allegations in the country. While the peacekeepers have made gains in protecting civilians, the allegations of sexual misconduct have tainted their work.

Conflict-related Sexual Violence, Exploitation and Abuse in CAR

Levels of sexual violence often rise in crisis and conflict settings, where systems of protection, security and justice break down and women and children are left particularly vulnerable. Reports indicate that the militia in CAR have used rape to deter women from undertaking economic activities. Other cases indicate that perpetrators used rape to punish women and girls suspected of interacting with people on the other side of the sectarian divide. Further compounding this scourge are reports of SEA by peacekeepers in the country. While carrying out their responsibilities, peacekeepers are expected to uphold principles of good conduct and discipline and not violate the rights of the host community. When peacekeepers sexually or otherwise exploit the vulnerability of the people they have been sent to protect, it is a fundamental betrayal of trust. Prosecution of the peacekeepers implicated in these allegations – once substantiated – is the responsibility of the member states. The lack of adequate national capacity and expertise to investigate and prosecute acts of sexual violence remains one of the main impediments to ensuring accountability for such crimes.

Cases and Allegations

The allegations documented by the UN Conduct and Discipline Unit, as at 31 November 2015,3 reflect that in 2015, 22 allegations have been made against its peacekeepers in MINUSCA – a mission only established in 2014. Nineteen of these allegations implicated the military, two implicated the police and one implicated civilian personnel. So far, in 2016,4 22 allegations have been made against peacekeepers in MINUSCA; 19 of these allegations implicate the military, two implicate the police and one allegation is yet to be accounted for in terms of the mission component category responsible. These numbers are suspected to be higher, noting that there may be more allegations that were not reported.

SEA Allegations for All Categories of UN Personnel per Year5

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 20156 | |

| Allegations (total)7 | 127 | 83 | 112 | 85 | 75 | 60 | 66 | 52 | 69 |

| Civilians | 32 | 26 | 35 | 30 | 22 | 23 | 20 | 14 | 15 |

| Military | 56 | 49 | 55 | 38 | 40 | 19 | 37 | 25 | 38 |

| Police | 24 | 7 | 16 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 13 | 16 |

| Unknown | 12 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| MINUSCA | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | No data | 22 |

In 2015, Human Rights Watch documented at least 25 cases8 of sexual violence in CAR. This was followed by other allegations, reported recently in 2016, of UN peacekeepers sexually abusing or exploiting at least eight women and girls, including the rape of a 14-year-old girl and the gang-rape of an 18-year-old woman. Other reports by Amnesty International9 and Médecins Sans Frontières document similar allegations. Distinctively and increasingly, most of the cases reported involve minors.

Vulnerabilities of Children to Sexual Violence, Exploitation and Abuse in CAR

Conflict situations create new protection risks and exacerbate children’s vulnerability to violence, exploitation and abuse. Further, poverty renders children vulnerable to exploitation, neglect and abuse. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recently highlighted the continuing allegations of the SEA of minors in CAR by members of foreign military and police forces in 2014, 2015 and 2016. Sexual activity with children (persons under the age of 18) is prohibited, regardless of the age of majority or age of consent locally.10 Mistaken belief regarding the age of a child is not a defence.11 Ten of the 22 allegations reported to have been committed by MINUSCA peacekeepers in 2015, and 18 of the 22 allegations reported in 2016, involved minors.12 This translates to 45.5% of all MINUSCA allegations involving minors in 2015 (10 out of 22), and 81.8% of all MINUSCA allegations involving minors in 2016 (18 out of 22). Thus in comparison with all the UN Missions, in 2015, MINUSCA recorded allegations involving minors standing at 43.5% (10 out of 23 cases); in 2016, MINUSCA is at the lead with allegations involving minors standing at 100% (all 18 cases) as at end of February 2016.13 In 2014, the records stood at 13 cases involving minors in all UN missions. This increase in the involvement of minors in recent years is a worrying trend, with 2016 numbers already at 18 in the first quarter of the year. Other allegations, implicating French troops, involved boys as young as 11 years old – more often in exchange for basic needs such as bottled water and food. Allegations also indicate that members of a European Union (EU) peacekeeping contingent raped two girls and paid two others for sex. The girls were 14–16 years old at the time. The children who reported the violations also indicated that they knew of other children who had been repeatedly sexually abused by peacekeepers.

The Reasons for Sexual Violence, Exploitation and Abuse

Social and economic factors can influence and shape the decisions made by the civilian population. Poverty, conflict, lack of education and unemployment can all contribute to vulnerability and exploitation. The scarcity of economic opportunities for displaced populations may result in commercial and exploitative sex as a means of income generation to meet basic needs. In addition, the support system for children has been weakened by conflict, which makes them vulnerable to sexual predators. Some peacekeepers exploit these situations to commit rape and other forms of SEA. The recent abuse allegations implicating French troops are reported to have involved children living on the streets. In the displacement camps, levels of protection and security are generally poor, and justice and policing is weak. Most of the abuse cases reported were against young boys, girls and women around the camps. There are also glaring gaps in holding perpetrators accountable. When cases are reported, far too many of these crimes continue to go unpunished, with the perpetrators enjoying impunity.

Few awareness-raising efforts have been carried out among vulnerable groups in the wake of the escalation of sexual violence. The peacekeeping environment has been described by many as stressful, mostly due to factors such as exposure to atrocities, alien culture and battle fatigue, among others, which can adversely affect the adjustment of soldiers in mission environments and may lead to them committing SEA acts. The 12 361 peacekeepers serving in MINUSCA as at December 201514 are of 48 different nationalities. They bring with them to the mission their cultures, attitudes, experiences and perceptions on gender and human rights.

Unintended Consequences of Peacekeeping: The Impact of Conflict-related Sexual Violence, Exploitation and Abuse

While the arrival of peacekeeping personnel has the obvious advantage of providing the local population with an increased sense of security, it may also have some negative repercussions. SEA threatens the well-being of individuals and communities, and undermines the legitimacy of peacekeeping missions. The presence of peacekeepers in an environment has been reported to be a trigger for increased prostitution, thus leading to cases of sexually transmitted diseases and the related risks of HIV transmission. SEA can have serious and irreversible consequences that threaten the physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development of children, and even their survival. Sexual violence, exploitation and abuse, particularly involving minors, affects the child’s mental health, cognitive and emotional orientation to the world, often resulting in low self-esteem. It also causes trauma by distorting their self-concept and affective capacities. Pregnancy as a result of sexual violence, and the plight of children born of rape by peacekeepers, is a consequence that affects the life of the victim or survivor for a very long time. SEA, particularly through rape, exposes women and girls to reproductive health challenges, and some may not have children in the future or may develop other health complications. Sexual violence and SEA present foundational constraints on women’s and children’s capacities to exercise their citizenship rights and their societal roles, and to contribute fully to reconciliation. SEA also hinders the local promotion of gender equality – an objective that the peacekeepers are supposed to promote. Further, experiences of survivors of CRSV indicate that complete healing is a prerequisite for peacebuilding and sustainable development; without the healing of the body, mind and soul, they cannot engage fully in building sustainable peace in their communities.

What is Being Done to Prevent and Respond to SEA?

After numerous allegations of SEA committed by UN peacekeepers and other foreign peacekeepers in CAR, several efforts and measures have been taken to respond to the abuse allegations and to prevent any further SEA by peacekeepers.

Investigations: The responsibility for investigating SEA allegations by UN peacekeepers and taking subsequent disciplinary action rests with the troop- and police-contributing country. The EU, Georgia, France and other European countries are investigating the alleged crimes, including rapes, mostly committed in 2014. The UN undertakes its own investigation if the countries implicated do not respond to the UN’s request to take the lead on the matter. Further, since 2014, the International Criminal Court has been conducting investigations in CAR. Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda adopted a policy paper on sexual and gender crimes in June 2014, and pledged to make these crimes a priority in investigations by her office. More recently, more than 10 years after the Zeid Report,15 the UN appointed an independent panel of experts to look into the allegations of SEA by peacekeepers in CAR, including French troops, and how the UN handled the SEA allegations.

Leadership and responsibility: Highlighting the commitment to zero tolerance of SEA, and following reports on the allegations of SEA by MINUSCA peacekeepers, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon called for and accepted the resignation of Babacar Gaye of Senegal, who was head of MINUSCA. Further, senior military leaders16 from Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Togo met in January 2016 for a sensitisation workshop on SEA within the context of peacekeeping operations.

Feedback loop and information-sharing: The UN has continued to correspond with member states on the allegations made against UN peacekeepers, requiring them to complete investigations on SEA within six months and report back to the UN on the outcomes of investigations and actions taken.17 The disciplinary sanctions and any other judicial actions taken against the individuals involved are not often shared with the survivors of SEA.

The years 2013, 2014 and 2015 reflect more interactions and responses by member states compared to preceding years, indicating an increased commitment to responses relating to SEA.

A human rights-based approach: The 2015 report titled Taking Action on Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by Peacekeepers,18 emphasised SEA being a human rights issue, besides it being a criminal offence. This reflects similar recommendations by the UN Peace Operations review (2014), as well as the global study on UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2015). In February 2016, the UN Secretary-General appointed Jane Holl Lute as Special Coordinator, to improve the UN response to SEA committed by peacekeepers and facilitate the better alignment of peacekeeping and human rights systems.

A disciplinary approach: Implementing zero tolerance to SEA has recently led to the mission’s repatriation of 120 DRC troops, following allegations of SEA in CAR. A recent UN Resolution 2272 (2016) reinforces the UN’s action of replacing all units of troop or police-contributing countries whose peacekeepers are implicated in SEA allegations. The UN has also adopted (and implemented) a new policy of suspending payments – which countries normally receive for the troops they contribute to peacekeeping missions – to countries where allegations are credible. The money that is suspended is expected to go into a trust created by the UN for victim assistance and support initiatives. The Secretary-General has also announced that countries whose troops and police are serving in UN peacekeeping missions and are facing credible accusations of SEA will be listed on a website, scheduled to be ready in March 2016. In addition, the Secretary-General announced that countries which are repeatedly listed in annual reports on children and armed conflict, and on CRSV, will not be allowed to participate in peacekeeping.

Coordination, synergies and collaboration: The establishment of a police force joint brigade to identify SEA perpetrators and deter the occurrence of new cases is one of the steps underway in MINUSCA. This will be complemented by increased patrols in the displacement camps, in close collaboration with CAR security forces. The UN is working with civil society organisations (CSOs) in CAR to implement victim assistance programmes for victims and children born out of SEA. OHCHR is also planning to carry out joint actions, as part of the reinforcement of MINUSCA’s ability to combat SEA.

Regional frameworks: The Pact on Security, Stability and Development in the Great Lakes Region, adopted by the heads of state and government of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) in 2008, contains the Protocol on the Prevention and Suppression of Sexual Violence against Women and Children. The UN and AU have also condemned acts of CRSV and SEA in the region. This is reflected in the UN-AU joint framework, signed in 2014,19 on the prevention and response to CRSV in Africa. In addition, similar sentiments are emphasised in the framework of cooperation between ICGLR and the UN Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict (SRSG-SVC), signed in 2014.20

The Role of Female Peacekeepers in Prevention and Response to SEA |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not a single female peacekeeper has been accused of SEA in MINUSCA. Further, women’s participation in the security sector at all levels has been recognised as a critical component of mission success. The UN encourages this role and emphasises the inclusion of women in peacekeeping missions in civil, military and police functions, recognising that their presence may encourage women from local communities to report acts of sexual violence.

Gender Statistics in MINUSCA Uniformed Personnel (Strength of 12 361) as at December 201520

In 1993, women made up 1% of the UN’s deployed uniformed personnel. As at December 2015, MINUSCA had 1.3% female military representation and 7.7% female police representation. Most CAR abuse victims point out military personnel as the major perpetrators, with few allegations implicating the police and civilians. Among member states from the Great Lakes Region, the DRC has been implicated in allegations of SEA, and some of its peacekeepers were sent back home. As at December 2015, the DRC had a total of 919 peacekeepers serving in MINUSCA, amounting to 7.43% of the mission force (out of 12 361). They included formed police units, comprising 101 males and 17 females, and contingent troops, comprising 799 males and two female soldiers.22 The percentage of female peacekeepers from DRC is 2.07%. The rape and SEA allegations reported often reflected gang rape by male peacekeepers. If there were female peacekeepers in these groups of male peacekeepers, chances are that the male peacekeepers would not naturally commit these acts. The presence of women raises the awareness of women’s issues and improves operational effectiveness. Thus, the presence of female peacekeepers can act as a deterrent to sexual violence, exploitation and abuse. Therefore, it is key to encourage and support member states to deploy more female military and police officers to peacekeeping missions. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

Allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers were first reported in 2004. Twelve years later, we are still reading about the increase in the misconduct of peacekeepers. The UN and the international community have strengthened their efforts in preventing abuse; however, more needs to be done.

Economic empowerment: Issues of poverty often lie behind all forms of exploitation. Reports indicate that transactional sex with peacekeepers earns women food or 1 000 CFA (approximately US$1.60).23 Thus, programmes that address livelihood issues and provide appropriate job training, income-generation schemes and credit for micro-enterprises are vital in preventing exploitation. These potential solutions go hand in hand with the provision of basic needs such as food, shelter, health and security.

Attitude change and a human rights approach: Peacekeepers should be trained in human rights issues, with the aim of changing their attitudes towards the rights of women and children. Peacekeepers who come from countries with better records of gender equality may hold values that are more in line with treating women as their equal, instead of potential sources of exploitation. Human rights should be at the heart of all peacekeeping operations. There is the need for strengthened modalities for AU–UN peacekeeping transitions, ensuring strict adherence to the human rights screening policy and capabilities.

A conducive environment for prevention and response: Peacekeepers are obliged to create and maintain an environment that prevents SEA and promotes the implementation of the agreed code of conduct in a peacekeeping environment. Managers at all levels have particular responsibilities to support and develop systems that maintain this environment.

Strengthen leadership, command and control in prevention: As stipulated in UN Security Council Resolution 1960, missions should hold all peacekeepers in leadership positions accountable for the actions of their teams, including sexual misconduct. Thus, early warning systems on SEA should be strengthened, and better checks and balances for managers and commanders at all levels should be introduced.

Accessible, inclusive and responsive reporting mechanism: MINUSCA and other foreign peacekeeping forces in CAR should ensure that complaint mechanisms for reporting SEA are accessible to the civilian population. When SEA allegations came to light through a confidential report (not publicly released) on the sexual abuse of children by French and other peacekeeping troops in CAR – the Sexual Abuse on Children by International Armed Forces Report, delays were reported in providing the children with basic medical care, psychological support, shelter, food, and protection. There were further claims that no steps were taken to locate additional child victims to determine if they also required protection and care. The loop between reporting and response should therefore be strengthened to ensure that all victims receive support. There is the need for more mechanisms or avenues for the community to report cases of SEA by peacekeepers and other armed groups – for example, the establishing of a SEA reporting hotline. There is also the need to strengthen community-based protection and response systems, by involving families and communities in identifying areas and situations of vulnerability for women and children.

Establishment of an international tribunal for SEA by UN peacekeepers and UN staff in the field: Once SEA allegations are reported, investigations completed, and the allegations substantiated, the UN cannot prosecute the peacekeepers implicated in these SEA allegations; this responsibility rests with member states. It is recommended that the UN General Assembly should authorise the establishment of an international prosecuting mechanism. This will be a professional investigative capacity (staffed by experts who have experience in sex crime investigations) to probe allegations of SEA by peacekeeping personnel.24 This can be complemented by an on-site court-martial for SEA allegations and can facilitate access to witnesses and evidence in the mission area, as well as demonstrating to the local community that there is no impunity for acts of SEA by members of military contingents.

Protecting and encouraging whistleblowing: A senior UN official, Anders Kompass, director of Field Operations and Technical Cooperation Division, OHCHR, was suspended following accusations of him breaching UN protocols by leaking details of a confidential report on the sexual abuse of children by French peacekeeping troops in CAR. While he was later exonerated, this trend discourages other peacekeepers who may want to blow the whistle on such violations. Thus, more needs to be done to create favourable conditions for whistleblowers to report cases of SEA.

Strong communication and feedback loop: The communication loop is weak, and troop-contributing countries fail to advise the local civilian population (or the victims) of the steps taken towards delivering justice. This gives the perception that nothing is being done. This is damaging – not only for the individual victim, but also for the relationship between the civilian population and the mission. Effective and visible means of bringing offenders to justice is an extremely important factor in deterring exploitative behaviour. Therefore, accountability to the beneficiary community should be strengthened and institutionalised.

Establishment of rapid response teams: The UN should establish immediate response teams within the mission that are able to deploy immediately, or in one to two days, to collect and preserve evidence and protect victims. This should be part of a larger strategy that also involves strong in-country partnerships, consisting of community-based organisations and CSOs which provide support to victims.

Effective child protection strategies: Specific strategies to address the challenges faced by street children and children separated from their parents in conflict situations should be developed. States must respect and promote the rights of children living in poverty, including by strengthening and allocating the necessary resources for child protection strategies and programmes.25 All contributing countries must ensure the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child through national action plans. If the peacekeepers are exposed to these frameworks in their home countries, they will be expected to respect similar frameworks in the peacekeeping environment.

Strengthen an evidence-based approach: A stronger evidence base – as indicated in the International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict26 – will lessen the burden on survivor testimony as the basis for prosecutions, as well as ensuring that victims are not further stigmatised or traumatised by the trial process. To avoid repeated stigmatisation, an audio or video recording of the child victim’s story could be made, so that child victims do not have to repeat the story many times, or tell it when the criminal is in the same room.27

Strengthen the capacity and capability of justice sector actors: The judiciary, police, magistrates, prosecutors and advocates/lawyers are part of the prevention and response cycle, and their capacities should be further strengthened to handle allegations of sexual violence crimes appropriately. This goes hand in hand with improved systems, strengthened institutions (including laws and policy) and greater synergy between national and international approaches. The ICGLR Regional Training Facility (RTF) on Prevention and Suppression of Sexual Violence in the Great Lakes Region runs training programmes to strengthen the capacity of military justice systems within ICGLR member states to investigate and prosecute cases of sexual violence and related crimes. The facility is still new and should be supported to cover the region.

Conclusion

Sexual violence in conflict is now recognised as a core security challenge. Women and children are frequently the targets of sexual violence before, during and after armed conflict, with rape, sexual slavery and other forms of SEA increasing. The issue of SEA by peacekeepers and humanitarian workers remains a problem for the UN – one that requires effective and strong action. Many allegations are not properly investigated by member states – or are considered unsubstantiated – and when resolved, the perpetrators get very lenient disciplinary measures or criminal sentences. Strengthening the prevention of and response to CRSV, exploitation and abuse therefore calls for pragmatic reforms at the national, regional and international level. Protecting and promoting women’s human rights and resolving the problem of SEA by peacekeeping personnel is a shared responsibility, and can only succeed with firm commitment and action by the UN, member states and non-state actors. There is much to be done to implement a zero tolerance policy on sexual violence, exploitation and abuse – noting that immunity must not mean impunity. Training for peacekeepers on the protection of human rights should be continuous. Sustainable funding is also necessary for building long-term sustainable engagement with communities, therefore funding for frontline responders should be long term and not only focused on emergency phases. All these measures should be complemented by physical protection and the economic empowerment of the community (especially women and children) to reduce their vulnerability to sexual violence, exploitation and abuse. Further, cooperation among the different professionals involved in managing cases of SEA is essential to avoid revictimisation in the judicial process.

Endnotes

- MINUSCA (n.d.) ‘MINUSCA Background’, Available at: http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/minusca/background.shtml [Accessed 5 December 2015].

- Uniformed (police and military) peacekeepers from ICGLR are: Burundi (1 134), Republic of Congo (906), DRC (919), Kenya (13), Rwanda (1 276), Tanzania (1) and Zambia (774). United Nations (2015a) ‘UN Mission’s Contributions by Country, Month of Report: 31-Dec-15’, Available at: http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/contributors/2015/dec15_5.pdf [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (2015) ‘Statistics – Allegations by Category of Personnel per Mission (Sexual Exploitation and Abuse)’, Available at: https://cdu.unlb.org/Statistics/AllegationsbyCategoryofPersonnelSexualExploitationandAbuse/AllegationsbyCategoryofPersonnelPerMissionSexualExploitationandAbuse.aspx [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (2016) ‘Statistics – Allegations for All Categories of Personnel per Year (Sexual Exploitation and Abuse)’, Available at: https://cdu.unlb.org/Statistics/AllegationsbyCategoryofPersonnelSexualExploitationandAbuse/AllegationsforAllCategoriesofPersonnelPerYearSexualExploitationandAbuse.aspx [Accessed 10 March 2016].

- Ibid.

- The data reflects UN Investigations Division of the Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) reports dated up until 29 February 2016.

- Civilian personnel includes UN staff members and UN volunteers; military personnel includes contingent personnel and military observers; police refers to UN Police, including Formed Police Units; unknown refers to unidentified subjects; other includes consultants and employees of UN contractors. UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (2015) op. cit.

- Human Rights Watch (2015) ‘Central African Republic: Amid Conflict, Rape’, Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/17/central-african-republic-amid-conflict-rape [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- Amnesty International (2015) ‘CAR: UN Troops Implicated in Rape of Girl and Indiscriminate Killings Must be Investigated’, Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/08/car-un-troops-implicated-in-rape-of-girl-and-indiscriminate-killings-must-be-investigated/ [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2003) ‘Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse’, Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/405ac6614.html [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- See Report of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Task Force on Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in Humanitarian Crises of 13 June 2002, Plan of Action, Section I.A.

- UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (2016) ‘Statistics – Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Allegations per Mission Involving Minors’, Available at: https://cdu.unlb.org/Statistics/SexualExploitationandAbuseAllegationsInvolvingMinors/SexualExploitationandAbuseAllegationsPerMissionInvolvingMinors.aspx [Accessed 10 March 2016].

- Ibid.

- United Nations (2015) op. cit.

- United Nations (2005) A Comprehensive Strategy to Eliminate Future Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in United Nations Peacekeeping Operations [hereinafter Zeid Report], UN Secretary-General Report A/59/710, 24 March.

- These countries have troops serving in CAR.

- UN Conduct and Discipline Unit (2015d) ‘Statistics – UN Follow-up with Member States (Sexual Exploitation and Abuse)’, Available at: https://cdu.unlb.org/Statistics/UNFollowupwithMemberStatesSexualExploitationandAbuse.aspx [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- Deschamps, Marie, Jallow, Hassan B. and Sooka, Yasmin (2015) Taking Action on Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by Peacekeepers. Report of an Independent Review on Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by International Peacekeeping Forces in the Central African Republic. New York: United Nations, p. 2.

- Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Sexual Violence in Conflict (2014a) ‘Joint Communiqué with the African Union and the United Nations on Framework of Cooperation to Prevent and Respond to Conflict-related Sexual Violence’, Available at: http://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/joint-communique/joint-communique-with-the-african-union-and-the-united-nations-on-framework-of-cooperation-to-prevent-and-respond-to-conflict-related-sexual-violence/ [Accessed 20 December 2015].

- Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Sexual Violence in Conflict (2014b) ‘Framework of Cooperation between the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region and the United Nations Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General’, Available at: http://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/joint-communique/framework-of-cooperation-between-the-international-conference-on-the-great-lakes-region-and-the-united-nations-office-of-the-special-representative-of-the-secretary-general/ [Accessed 20 December 2015].

- United Nations (2015) op. cit.

- Off, Carol (2015) ‘As it Happens: Graça Machel Demands the UN Stop Sex Abuse by Peacekeepers’, Available at: http://www.cbc.ca/radio/asithappens/as-it-happens-wednesday-edition-1.3072550/gra%C3%A7a-machel-demands-the-un-stop-sex-abuse-by-peacekeepers-1.3072861 [Accessed 24 November 2015].

- United Nations (2015b) ‘Gender Statistics by Mission for the Month of December 2015’, Available at: http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/contributors/gender/2015gender/dec15.pdf [Accessed 24 January 2016].

- Ibid. [Accessed 26 January 2016].

- Human Rights Watch (2016) ‘Central African Republic: Rape by Peacekeepers’, Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/02/04/central-african-republic-rape-peacekeepers [Accessed 5 February 2016].

- UN Women (2015) Preventing Conflict Transforming Justice Securing the Peace: A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. New York: UN Women, p. 149.

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) (2012) ‘Guiding Principles on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights’, Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/OHCHR_ExtremePovertyandHumanRights_EN.pdf [Accessed 27 March 2015].

- Foreign & Commonwealth Office and The Rt Hon William Hague (2014) ‘Chair’s Summary – Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict’, Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chairs-summary-global-summit-to-end-sexual-violence-in-conflict/chairs-summary-global-summit-to-end-sexual-violence-in-conflict [Accessed 27 March 2015].

- Office of the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Violence against Children (2013) ‘Raising Understanding among Children and Young People on the OPSC – Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography (OPSC)’, Available at: http://srsg.violenceagainstchildren.org/sites/default/files/children_corner/RaisingUnderstanding_OPSC.pdf [Accessed 12 January 2016].