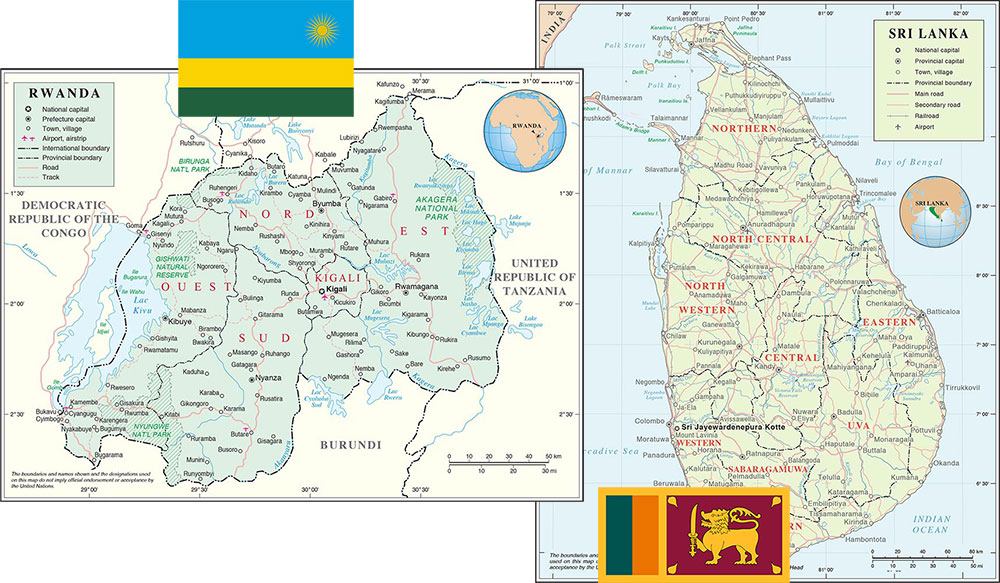

The thrust of this comparative analysis is to examine the extent to which reconstruction processes in Sri Lanka and Rwanda lead to social reconciliation, and the strengths and weaknesses of the divergent mechanisms of reconciliation adopted in the two countries. The process and outcomes of reconciliation and the effectiveness of different mechanisms are subject to debate and discussion. This article argues that Rwanda and Sri Lanka have succeeded in certain respects but failed in others, and hence can learn lessons from each other. How do countries coming out of wars achieve reconciliation among the polarised ethnic groups? Do we have sufficient knowledge on efficient and effective mechanisms of fostering reconciliation and stabilising peace? I try to respond to these key questions through a larger study on peace education in Rwanda in which I was one of the researchers, and several research endeavours in Sri Lanka in the last five years.

The term “reconciliation” has Latin roots and is derived from the Latin expression conciliatus, which means “coming together”. Reconciliation is social when such a process involves social groups rather than individuals. Kumar1 argues that in the general understanding, social reconciliation refers to a process of re-establishing the broken relationships between social groups. Therefore, at a very basic level, social reconciliation must begin with former enemies accepting each other’s right to exist. Then, a process of social reconciliation attempts to promote tolerance and understanding between and/or among groups, to promote non-violent conflict resolution, and finally to heal the wounds of violence in the long term.2 There are three objectives of a process of social reconciliation: to prevent violent conflict, to address negative emotions (anger, prejudices, misunderstandings), and to establish or re-establish positive relationships among the conflicting parties. Scholars also agree that reconciliation aims to address the trauma experienced by the victims of conflicts to bring closure between the victims and the perpetrators. Reconciliation is a “reciprocal and gradual process” that attempts to make it possible for people to live together. Reconciliation essentially has three stages: simple co-existing, democratic reciprocity, and the reconstruction of bonds among former victims and perpetrators.3

Nurturing reconciliation among war-affected people is seriously challenging, both theoretically and empirically, but is an existential necessity. There is ample evidence to show that there are many cases of violent conflict in which conflicts have restarted after brief periods of relative peace, when parties to conflict feel that their needs have not been addressed. According to conflict resolution literature, the majority of conflicts in the world end in military victory for one of the parties. Although there are many success stories of conflict being solved through peace negotiations, most intrastate conflicts have generally tended to cease with a military victory for one of the protagonists.4 However, at the same time, most conflicts ceasing due to a military victory end up in renewed violence after a period of five to 10 years.5 The failure to address the underlying root causes of conflict and address original or subsequent grievances can cause post-conflict reconciliation to fail, and hence increase the risk of renewed violence. Military victories are rarely sustainable, especially while genuine grievances remain unaddressed – seeds for future conflict can gradually grow.

Sri Lanka and Rwanda have experienced violent conflicts in the past and have witnessed immense human cost in intrastate conflicts, although the human cost was massively greater in Rwanda. These countries can currently be identified as post-conflict societies, given that overt violence has ended. Rwanda entered the post-conflict phase after the 1994 genocide and when the former Rwanda government was overthrown by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) through its armed wing, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA). The RPA fought against the Interahamwe militia and government soldiers who committed the genocide against the Tutsi and certain sections of the Hutu community that opposed the genocide.6 Compared to Rwanda, Sri Lanka is a relatively new entrant to post-conflict status, after having won a three-decade war in 2009 against a rebel group, called the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The LTTE fought against the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) to carve out a separate homeland for the Tamil ethnic minority in Sri Lanka.7 When the Sri Lankan military defeated the LTTE in 2009, the conflict – at least the military confrontations – ended.

The conflicts in Sri Lanka and Rwanda have both parallels and stark dissimilarities. In both cases, ethnic segregation and polarisation, fuelled by politics of ethno-nationalism, was at the root of the conflicts. Both countries involve a government and a rebel group, representing the majority and minority ethnic groups respectively. In both cases, colonial interventions used “divide and rule” policies, fuelled hatred between communities and solidified the significance of ethnicity as a source of mobilisation. And in both cases, there were grievances attached to ethnicity and post-independent discrimination of a minority by the government, which largely represented the majority ethnic community. However, despite a high number of battle-related deaths (60 000–70 0008) in Sri Lanka, the intensity of violence was nowhere near that of Rwanda, which is considered to be one of the deadliest genocides in human history. Nevertheless, in the Sri Lankan conflict, both the GOSL and the LTTE have been accused of serious and gross violations of human rights. Therefore, these two conflict settings provide interesting cases to compare from the point of view of conflict and post-conflict dynamics.

There is another sense in which both these cases warrant serious systematic academic scrutiny: as mentioned, both countries presently experience post-conflict reconstruction in which social reconciliation supposedly constitutes an important component. The Rwandan government claims to be attempting to build “one nation”, devoid of ethnic divides. For example, the Rwandan government has banned the use of ethnic labels such as Hutu, Tutsi or Tva and compels its citizens to identify themselves as “Rwandans”, and tries to build cooperation between formerly antagonistic groups through grassroots cooperative activities. The Rwandan government is determined to downplay the social and political significance of ethnic identity or differences, and this approach is predicated on the belief that by creating a common identity as a Rwandan, the country will be able to heal the wounds of violence and roll back on polarisation. Nevertheless, ethnic identity and differences remain strong in Rwanda, and this issue requires political space where people have the freedom to express and negotiate their differences. The Sri Lankan government is attempting to build a society where ethnicity is recognised, acknowledged and expressed socially and politically, and groups can co-exist in peace. For example, the government, which came to power in 2015, reintroduced the national anthem in both Sinhala and Tamil, and has started teaching Sinhala and Tamil as compulsory subjects in primary education.

Some scholars point out that sponsoring material development in post-war contexts is one of the instruments of social reconciliation. Development can be a highly significant instrument for sustainable peace, especially in the context of civil wars where protagonists fight over the inequitable distribution of scarce resources. In such a context, there can be calls for the integration of development into peace processes as a conscious strategy aimed at sustainable peace.9 This argument is especially relevant in Sri Lanka, where both real and perceived inequitable distribution of resources among different ethnic groups was one of the causes of the ethnic conflict. For example, dry agricultural development in Sri Lanka from 1930 to the 1980s caused ethnic tensions between Tamils and Sinhalese. After the end of the war in 2009, Sri Lanka invested heavily in large-scale development projects in war-affected provinces, including the development of infrastructure such as roads, schools, hospitals, highways, railways, bridges, power plants, ports and state buildings. These investments have improved access to markets and essential services, and have fostered mutually beneficial interactions with the south of the country.

Similarly, in Rwanda, distribution of state resources – such as employment and education – was important in causing ethnic polarisation, and the current government has therefore undertaken an ambitious development drive. However, compared to Sri Lanka, one finds less attention on equitable material development in the grassroots in Rwanda as a conscious tool of reconciliation. Although certain attempts have been made to provide primary education to all children, and to support poor families, Rwanda still has high levels of poverty.

In terms of transitional justice, there is a significant difference between Rwanda and Sri Lanka. The Rwandan government appears to be determined to create a common identity and “one nation” to prevent a recurrence of violence. Although the Rwandan government highlights the need to create a viable socio-economic base, it was forced immediately to approach the issues of reconciliation, due to the large-scale involvement of the Rwandan people in the genocide. From the very inception of the reconstruction process, Rwanda has emphasised and implemented a conscious strategy of transitional justice10 and various programmes such as cooperatives (where people of a village work together for community development); the Ndi umunyarwanda programme (“I am Rwandan” campaign, where people talk about history, repent on past crimes committed on the other ethnic group, and heal); Umuganda (a day dedicated to collective community work such as cleaning infrastructure, repairing roads and so on, once a month); Umugoroba w’ ababyeyi (parents’ evening, where parents of the same village talk about various issues, from politics and development to family issues) and Ijisho ryúmuturanyi (eye of the neighbour), as well as many other measures intended to foster social reconciliation. These measures have seen various levels of success and failure. Some case studies in Rwanda commend that the structure of cooperatives in Rwanda – due to long-term interactions and gradual relationship-building – contributes to genuine reconciliation among direct victims and perpetrators of the genocide.11

In comparison to Rwanda, Sri Lanka has failed to give sufficient priority for social reconciliation, and instead has employed a strategy of development-led material reconstruction. Although the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) was appointed, its mission was more fact-finding in nature, and many of its recommendations remain to be implemented. Meso-level and grassroots measures – such as peace committees or forums that bring formerly divided communities together – have been absent in Sri Lanka, although non-governmental organisations have undertaken micro measures such as youth exposure visits, awareness meetings, youth camps and so on. War-affected people find few opportunities to express their painful memories, mourn their dead relatives and find emotional closure to the wounds of violence. Therefore, one could argue that attention on social reconciliation has been inadequate in Sri Lanka, except perhaps the setting up of the Office of Missing Persons (OMP). The GOSL hoped that the physical and economic development of war-affected regions of the country would help it to win the hearts and minds of the Tamil community, which had been backing the LTTE for nearly three decades to procure them a separate homeland.12 The GOSL seems to believe that a recurrence of the conflict will be prevented by addressing material conditions – which initially contributed to creating the ethnic conflict.

Challenges

Both Rwanda and Sri Lanka face the serious challenge of bringing together highly polarised ethnic groups, which were set apart by a history of ethnic polarisation, perceived as well as real discrimination, prejudices and violence. In both cases, the military victory of one party against another has brought the conflict to a halt. Yet, ethnic prejudices, mistrust, and perceived and real discrimination continue to plague the two countries – and hence, the possibility of relapsing into violence remains real. Based on data collected in the two countries, including my observations,13 it is possible to state that both Rwanda and Sri Lanka have made significant strides in their post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation. Economic development in Rwanda has picked up in the capital city, although the rural areas need much more investment and state patronage. Primary education has been opened up and made compulsory, but it is higher education that determines socio-economic mobility; opportunities to get a higher education needs improvement. Rwanda has undertaken large-scale judicial scrutiny of cases of perpetrators and has used the Gacaca courts14 as an alternative for judicial review. This has enabled a rapid transitional justice process. However, there are still a large number of people awaiting trial. Any viable reconciliation process requires solid democratic space and a vibrant civil society so that people are able to debate, critique and change in their methods of reconciliation. Rwanda requires further scrutiny and constant reconsideration of its methods to improve post-conflict reconciliation.

In Sri Lanka, elections have been held in the war-affected provinces, and have enabled people to choose their provincial representatives. At the grassroots, significant attention has gone into the reconstruction of houses and basic facilities, such as schools and health facilities. Nevertheless, unlike in Rwanda, attention to social reconciliation has been weak in Sri Lanka, and there are criticisms that material development alone has not been able to win the hearts and minds of the people. Although certain strategic measures – such as the singing of the national anthem both in Sinhala and Tamil, and the rehabilitation of former rebels – have been undertaken, concrete measures for reconciliation have been weak. The north and east of Sri Lanka have also suffered various social and emotional break-ups as a result of the war, and these remain largely unaddressed so far. Such social and emotional break-ups include marital instability among war-affected people, more suicides, increased alcoholism and a high prevalence of household violence.15 These are the social wounds of the war, which require the strong intervention of both the government and non-governmental actors. Although the Sri Lankan reconciliation process has marked some important achievements, there is a long road ahead and more concrete actions needed.

Conclusion

Rwanda and Sri Lanka are both interesting post-conflict cases, having remarkable similarities as well as profound differences – which makes them attractive for qualitative comparative analysis. Both countries have a history of colonial interventions, ethnic prejudices, polarisation and violence – and both currently implement post-conflict reconciliation programmes. This article has argued that the approach of the two countries is rather different. Rwanda has taken concrete measures towards transitional justice but is weak in terms of economic restoration, equitable grassroots development, providing essential services, restoration of vital infrastructure and access to health and education. Sri Lanka, on the other hand, has invested massively in the economic development of the former conflict-affected regions and has fared well in terms of economic restoration, provision of basic services and improving infrastructure and livelihoods, but has been weak in terms of transitional justice and social reconciliation. Further, Rwanda is trying to supress ethnic identity to create a common nation and common identity, whereas Sri Lanka is consciously facilitating expression and the recognition of ethnic identity. Therefore, the outcomes of their reconciliation programmes remain somewhat incomplete and weak in relation to the efforts made in each context and impacts on long-term peacebuilding. Therefore, there is much that these two countries can learn from each other to ensure that their social reconciliation is more effective.

Endnotes

- Kumar, Krishna (1999) ‘Promoting Social Reconciliation in Post-conflict Societies: Selected Lessons from USAID’s Experience’, US Agency for International Development, Available at: <http://pdf.dec.org/ pdf_docs/pnaca923.pdf> [Accessed 20 September 2010].

- Herath, Dhammika (2012) Wounded Society: Social Wounds of the War and the Breakup of Community Social Structures in Northern Sri Lanka. In Herath, D. (ed.) Healing the Wounds: Rebuilding Sri Lanka after the War. Colombo: ICES, pp. 49–80.

- Crocker, D.A. (2000) Forgiveness, Accountability and Reconciliation. Perspectives on Ethics and International Affairs, 2(7), pp. 13–40.

- Wallensteen, P. and Axcell, K. (1995) Armed Conflict at the End of Cold War. Journal of Peace Research, 30(3), pp. 331–46.

Miall, Hugh, Ramsbotham, Oliver and Woodhouse, Tom (1999) Contemporary Conflict Resolution. Cambridge: Polity, pp. 1–34. - Ibid.

- Melvern, Linda (2006) Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide. London and New York: Verso.

Prunier, Gérard (2008) Africa’s World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp 1–30. - De Silva, Kingsley M (2000) Reaping the Whirlwind: Ethnic Conflict, Ethnic Politics in Sri Lanka. Penguin, pp. 1–50.

Gunaratna, Rohan (2000) The LTTE and Suicide Terrorism. Frontline 17(3), pp. 5–8.

Loganathan, Ketheshwaran (1996) Sri Lanka: Lost Opportunities: Past Attempts at Resolving Ethnic Conflict. Centre for Policy Research and Analysis, University of Colombo, pp. 1–200. - An estimate based on the author’s fieldwork in Sri Lanka.

- Herath, Dhammika (2012) op. cit.

Smoljan, J (2003) The Relationship between Peace-building and Development. Conflict, Security & Development, 3(2), pp. 233–50. - Clark, Philip and Kaufman, Zachary Daniel (2009) After Genocide: Transitional Justice, Post-conflict Reconstruction and Reconciliation in Rwanda and Beyond. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 70–100.

Gahima, Gerald (2013) Transitional Justice in Rwanda: Accountability for Atrocity. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 25–55. - Sentama, Ezechiel (2009) Peacebuilding in Post-genocide Rwanda: The Role of Cooperatives in the Restoration of Interpersonal Relationships. Gothenburg: School of Global Studies, Peace and Development Research, pp. 10–100.

- Herath, Dhammika (2017) Breakup of Community Social Structures in the War-affected Northern and Eastern Provinces in Sri Lanka. Forthcoming publication under the current project. World Bank, pp. 30–50.

Herath, Dhammika (2012) op. cit. - My research study in Rwanda included interviews with government officials, university academics, students and civil society leaders in 2014 and 2015. Each collection segment took about four weeks, and interviews were done in Kigali.

- Gacaca courts are a grassroots mechanism for the trial of perpetrators, who make a public statement of crimes committed and render an apology.

- Herath, Dhammika (2017) op. cit.