Introduction

With the restoration of democratic order in the Gambia in 2017, the West African region regained the attention of the world with renewed hope and optimism for democratic consolidation in Africa. The Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) rejection of the undemocratic retention of power by former President Yahya Jammeh and its threat to apply force, coupled with Gambians’ resistance, resulted in the restoration of democratic order in the country. Similarly, ECOWAS’ preventive diplomacy efforts following the recent military incursion in 2021 affirmed the regional body’s zero-tolerance stance for power acquired through unconstitutional means. The practice of accessing political power through credible elections under the watch of civil society and international actors is progressively taking firm root across the region. However, despite these democratic gains, the region is also witnessing setbacks in emerging political developments across Member States.

According to the Freedom House ‘Freedom in the World Report 2021’, of the 12 countries with the most significant decline in democracy year-on-year, five are in West Africa.[1] The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index (2020) showed that only Ghana and Cabo Verde still qualify as fully-fledged democracies in the region.[2] Recently, the region has also witnessed a resurgence in military interregna in Mali and Guinea. This democracy backsliding portends political instability, and its attendant economic consequences for the ECOWAS is concerning considering the developmental agenda of the region. Central to this negative democratic trend are concerns around political reforms that have undermined electoral integrity, inclusiveness and legitimacy in Member States. The application of some of these reforms has fuelled crises, which have led to the resurgence of coups d’état and threatened stability, peace and security in the region.

Ordinarily, political reforms are critical for enhancing democracy and inclusive socio-economic development. But in the recent past, a number of problematic political reforms were introduced. These have favoured unconstitutional retention of power, on the one hand, and reforms that appear to be politically motivated and seek to exclude or disqualify key political opponents from contest, on the other hand.[3] Notably, change and/or modification of constitutions relating to eligibility for political leadership and term limits have been witnessed in Togo, Senegal, Cote d’Ivoire, and Guinea, among others. These constitutional reforms, which largely followed contentious processes, allowed incumbents to extend their term in power. In Togo, for instance, after changing the Constitution through a controversial legislative process, President Faure Gnassingbé, who had spent 14 years in office, contested and won the presidential election in 2019 amid sustained protests that saw at least 16 people killed.[4]

Today, the question of stability in West Africa is more prominent at regional, continental and global levels than it has ever been. ECOWAS and other international actors have called into question political reforms that have impacted governance dynamics and the sustainability of social, economic and political processes in the region. This is significant as the surge in instability came when the region, as in other parts of the world, witnessed the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic brought human suffering, uncertainty, and major economic disruption, among other unexpected challenges, while exposing the fragility of ECOWAS Member States. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the economy of sub-Saharan Africa will shrink by 3% due to the pandemic, which is ‘the worst outcome on record’.[5]Managing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic raised the stakes in the recent crises fuelled by the implementation of political reforms in the region. Stability in West African States is crucial to the security and economic prosperity of the region.

Leveraging its preventive diplomacy efforts, ECOWAS successfully managed the recent crises in Togo, Guinea, and Cote d’Ivoire.[6] Though ECOWAS was able to manage these crises through mediated solutions, the root causes of the political impasses that engulfed these countries might not have been necessarily addressed. The recent resurgence in coups d’état in Guinea and Mali indicate the need to overhaul ECOWAS’ democratic governance architecture because most of the reforms undertaken since 2015 in West Africa have resulted in a disconnection between the political elite and the people.[7] This trend has become an emerging trigger for democratic backsliding and instabilities in Member States and constitutes a litmus test for ECOWAS’ resolve in upholding the defence of democratic norms and standards for the consolidation of peace and security in the region.

Clearly, ECOWAS’ Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance was adopted over two decades ago to provide a concerted regional response to structural conflicts and instability in the region. The Protocol prohibits the modification of constitutions or electoral codes six months prior to elections unless such amendments receive the support of the majority of political actors. More critically, the possibility of an ostensibly ambitious incumbent government amending a constitution has allowed opportunities for abuse. Also, many other recent legal and policy reforms across Member States have explicitly or implicitly compromised inclusivity, fairness, integrity, the rule of law, and human rights – all of which are the hallmark of ECOWAS’ democratic norms and standards.

Under these prevailing circumstances, ECOWAS’ commitment to advancing democracy is faced with a dilemma in consolidating democratic gains and maintaining stability in the region. The regional body adopted normative and legal instruments to promote democracy and democratisation in Member States to maintain stability, peace and security. But the experiences of enacting and implementing political reforms in recent times have more or less fuelled instability, thereby posing a serious threat to peace and security in the region. ECOWAS’ normative and legal instruments have proven less appropriate to address the recent undemocratic political reforms in the region.

This article, therefore, addresses the question: Is ECOWAS well-equipped to prevent or manage political tenure elongation orchestrated through constitutional and electoral reforms in Member States? The article analyses the context of recent political reforms in West Africa, including political reforms induced by ECOWAS. The article examines the implications of recent political reforms for democracy and stability. It further suggests policy directions which ECOWAS and Member States can pursue to prevent and manage undemocratic retention of power through the combination of strengthened regional normative and legal instruments and technical support for Member States.

Context of Recent Political Reforms in West Africa

Political reforms have been an integral, although challenging, component of democratic transitions in West Africa. Managing the conflict that accompanies political transitions has been a critical factor in the enactment and implementation of political reforms in West Africa. For example, post-World War II political reforms brought about political self-determination and democratisation in West Africa and Africa at large.[8] The period 1990-1999, following the end of the Cold War, showed political reforms leading to multi-party systems and regular elections in practically all states in West Africa. However, reforms undertaken since 2015 in West Africa have often resulted in a disconnection between the political elite and the people.[9] This article, therefore, focuses on the recent change of national constitutions and other ancillary policies relating to political leadership, term limit, and inclusivity, which have increasingly become sources of instability in the ECOWAS region. The context of these reforms has been argued to be not only controversial, non-inclusive and untrustworthy, but also the reforms have either been tacitly exploited for tenure elongation by incumbents or constituted legal barriers that have prevented opponents from participating in elections.

Constitutional Reform Favouring Tenure Elongation

Respecting constitutionalism is a cornerstone of democratic governance. The constitution as a foundational norm of any nation is supreme. Its legal order and normative disposition guide the exercise of power, political governance, and electoral processes. West African States have embarked on a range of constitutional reforms to deepen democratic culture, peacebuilding, and sustainable development. For example, the repeal of the principle of ivorite in the Ivoirian Constitution has allowed more inclusive political processes and entrenched national unity and stability in Cote d’Ivoire. Comparatively, West African States have made significant strides in strengthening democracy.

However, in recent years, politicians have adopted more complex and sophisticated ways to retain power in the ECOWAS region. Recent constitutional reforms have implicitly reset the clock of tenure for incumbent leaders to zero in Togo, Cote d’Ivoire, and Guinea. The incumbents had reached their absolute term limit but argued that the new constitution enabled them to start with fresh mandates unrestricted by previous constitutional limits. In essence, by invoking the application of the non-retroactivity principle of law, newly adopted constitutions have been argued to have no legal effect on the previous term of office of incumbents. These countries embarked on such opportunistic reforms despite the track record of African leaders who have stayed in power at times for more than 10 years being marred by repression, corruption, financial instability, underdevelopment, and conflict.[10]

In Guinea, for example, despite having experienced 50 years of authoritarian rule and a legacy of misgovernance, former President Alpha Conde sought constitutional reform after 10 years to extend his stay in power. Some analysts have argued that the 2020 constitutional reform was illegitimate as it was singlehandedly authorised by the President of the National Assembly in contravention of the Constitution, which requires a consensual decision of Parliament to authorise a constitutional reform. Similarly, the credibility of the referendum for the adoption of the new Constitution has been called into question by some analysts as grievous irregularities marred the process. On the day of the referendum, local media outlets and social media reported that there were not enough ‘No’ ballots at some stations. Voter cards were confiscated, some were told to wait outside while someone else voted on their behalf, and others said they were forced to vote ‘Yes’.[11] The voter turnout was another source of disagreement between civil society actors and the government. While the former noted a turnout rate of 30% and less than 15% in Conakry, the government pegged the official turnout rate at 58%, with 89% voting for the adoption of the new Constitution.[12] While a number of people were killed,[13] the recent coup d’état has further exacerbated democratic decline in Guinea.

In Togo, the constitutional reform of May 2019, which was adopted in circumstances that have been described as controversial and non-inclusive, paved the way for a fourth and possibly 50-year mandate for the incumbent President Faure Gnassingbé in 2020. The boycott by the opposition coalition, C14, of the 20 December 2018 election enabled the ruling party, alongside its allied political parties, to secure a four-fifths majority in Parliament. Parliament adopted the new Constitution, which reinstated the two-term limit on the presidency as an absolute majority in Parliament could replace the need for a constitutional referendum. However, the prospective application of the Constitution allowed the incumbent to evade the two-term limit. While ECOWAS’ role in facilitating dialogue between the government and opposition groups could be commended, the legitimacy crisis with regard to Faure Gnassingbé’s presidency hampers efforts towards democratic consolidation in Togo.

While the scenario in Guinea and Togo also played out in Cote d’Ivoire, it is important to note that the cases of constitutional reforms across these ECOWAS Member States largely followed procedures set out in the relevant constitutions, as measures such as required majorities were achieved, and required referenda and/or legislative adoption were also realised. However, superficial compliance with constitutional requirements smartly disguised constitutional and legal manipulations, as the principle of non-retroactivity of law was invoked to justify tenure extension in these Member States. These practices defeat both legal and normative understandings of constitutionalism. Hence, beyond requiring that constitutional reform follow established constitutional procedure, ECOWAS and Member States must ensure that the process is legitimate, inclusive, and respects human rights and the rule of law.

Extra Constitutional Reforms in West Africa

Besides clear-cut constitutional reforms that have reset presidential terms to zero, incumbent governments have also adopted policies with exclusionary principles and/or exploited the restrictive interpretation and instrumentalisation of the judiciary to disqualify strong presidential opponents. Electoral reforms around the parrainage (sponsorship) policy were politically applied to undermine competitive and participatory democracy in ECOWAS Member States.

Parrainage Policy

Parrainage is a process of endorsement and sponsorship of candidates for elections. The policy, which is prevalent across Europe, requires a candidate to amass a number of signatures from citizens or elected officials in a specified number of regions across the country to be eligible to run in an election. The rationale for this policy is hinged on the need to address the proliferation of fanciful candidates, enhance competitiveness, and deepen the quality of elections.

Parrainage has been entrenched in the recent electoral reforms undertaken in some French-speaking ECOWAS Member States, but in marked variations in both the nature and substance of the policy. While some Member States adopted citizen parrainage, others preferred elected official parrainage. Due to the application of parrainage in Benin Republic, the number of registered political parties increased from 118 in 1998 to more than 250 in 2019, but has since been reduced to four major parties before the 2021 presidential election. As laudable as the parrainage system appears to be, its implementation has shown a deleterious interplay among democracy, equal participation, and politics across Member States. Implementing parrainage has led to abuse of democratic principles and manipulation of democratic institutions by the incumbent government for undue political advantage over the opposition.

Senegal, known for its frequent reforms, introduced parrainage for presidential aspirants of political parties and political formations in 2018. According to the Electoral Code as amended, a potential candidate is required to gather sponsorship from a minimum of 0.8% (53 457) and a maximum of 1% (66 820) of registered voters in at least seven regions, with a minimum of 2 000 per region.[14] Based on this requirement, the Constitutional Council announced the confirmation of only five eligible candidates (Macky Sall, Ousmane Sonko, Madicke Niang, Idrissa Seck and El Hadji Sall) out of 27 for the 2019 presidential election. The parrainage requirement was suddenly modified by the ruling government without the consent of the major political actors. This development heightened the already tense political environment as Senegal moved towards the election. In addition, the inability of the Constitutional Court to try this contentious reform before the 2019 presidential election raised serious rule-of-law concerns and undermined equal political participation. More importantly, the applicability and consistency of parrainage for the electoral framework will be a serious factor affecting instability in future elections in Senegal.

Furthermore, the list of sponsors, which is expected to contain sensitive information about electorates (names, dates and places of birth, and voter registration numbers), is attached to the endorsed candidate’s nomination form for the Constitutional Council’s validation and undermines the secrecy of voting. This approach to parrainage plays out as an election before the main election as the electorate declares in advance which candidate they intend to support since a voter can only endorse one candidate. In addition, this practice carries enormous risks for electorates who grant their sponsorship to a candidate as they may be subject to harassment and attacks by the opponent’s political party supporters. This concern, among others, served as the premise on which the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice ruled that the Senegalese government must restore the rights of disqualified candidates by abolishing the parrainage system which constitutes a real obstacle to the freedom and secrecy of the right to vote on the one hand, and a serious infringement on the right to participate in elections as a candidate, on the other hand.[15]

Conversely, Benin Republic and Burkina Faso operate grand electeurs parrainage as only elected officials are allowed by law to sponsor candidates for the presidency. In Burkina Faso, the January 2020 reform of the electoral code requires every presidential candidate to be sponsored by at least 50 elected officials. When sponsors are municipal councillors, they must be located in at least seven of the 13 regions of the country. In Benin Republic, the electoral code requires candidates to be endorsed by 10% of mayors or parliamentarians. The application of parrainage in the two countries created more obstacles for new political parties and independent candidates to participating in the electoral process as elected officials’ loyalty to their parties is undisputable, except in exceptional circumstances. Democracy is, therefore, at peril, particularly as old political parties have used parrainage as a tool to stifle equal access to competitive elections and limit citizens’ options for changing leadership. Parrainage may be worsening in countries like Nigeria and Ghana, where citizens have harkened to calls for alternative platforms as traditional political parties are increasingly losing their credibility and/or a party’s supremacy has hindered the emergence of credible candidates.

The Way Forward for ECOWAS

The costs of democratic backsliding for West African States and ECOWAS are high in terms of democracy, stability, human rights, reconciliation, violent extremism, security, and development. The implications of these political reforms explain the relationship among prolonged stays in power, instability, and violent conflict that the region has experienced. In fact, there is a strong correlation between these concerns and the recent resurgence in coups d’état in Mali and Guinea. Strengthening ECOWAS’ legal democratic instruments, including norms to enthrone good democratic practices and mechanisms to enhance checks and balances and democratic accountability against opportunistic reforms can help overcome democratic backsliding in the region. Also, Member States should undertake efforts to ensure that political reforms are consensual, inclusive, and emanate from credible and transparent processes. This is critical to complementing regional initiatives and ensuring that political reforms attain the goal of deepened political liberalisation, greater political accountability, and socio-economic development for the benefit of ordinary citizens.

Enhancing ECOWAS’ Legal Instruments

In spite of the significant potential of the Supplementary Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance for entrenching democratic practices and culture, lessons drawn from two decades of its implementation have revealed some of its weaknesses, particularly with regard to emerging political developments in the region. Issues around presidential term limits, constitutionalism, democratic institutions’ credibility, political reforms legitimacy, democratic support and enforcement mechanisms, as well as some cross-cutting issues like gender and human rights, are critical standards to be strengthened in the Protocol to upgrade its effectiveness, relevance and responsiveness.

Presidential Term Limit

ECOWAS’ principles on zero tolerance for power obtained or maintained by unconstitutional means and the fundamental principle of free, fair and transparent elections have come under criticism in the face of recent undemocratic trends and the retention of power through opportunistic reforms in Member States. Evasion of term limits by incumbents has undermined the efficacy of the Protocol.

In strengthening the Protocol, presidential two-term limits of varied duration (seven, five or four years) should be clearly institutionalised as part of the Constitutional Convergence Principles. Research has shown that countries lacking term limits tend to be more unstable, and a third of these 18 countries are facing armed conflict. In contrast, just two of the 21 countries with term limits are in conflict.[16] Term limits are not only a democratic principle that must be respected, their scrupulous implementation across Africa has demonstrated stability.

Having presidential term limits institutionalised in the constitution is not an end in itself. Rather, it is a means to ensure that leadership succession is structured and peaceful, while safeguarding democratic principles and maintaining stability. Other factors such as disregard for constitutionalism and ambiguous term limit provisions have undermined the effective application of presidential term limits in West Africa. In addressing these concerns, some Member States introduced an ‘unamendable clause’ in their constitutions to ensure that a term limit can never be changed. This approach is, however, less effective as it can hardly stand the test of legality when the principle of non-retroactivity of law is invoked when a new constitution is adopted to reset the clock for the incumbent president to zero. Therefore, moving forward, an important priority for ECOWAS is that presidential terms be made an absolute maximum of two, without prejudice to restriction on the number of consecutive terms a person may serve. This implies that no person can serve more than two terms as president, whether consecutive or not. Consequently, the 2015 proposal by the ECOWAS Commission to adopt a regional obligation on term limits could be re-introduced for consideration by the Authority of Heads of State and Government. The timing seems appropriate as Togo and Gambia, the two Member States that were antagonistic to the adoption of the presidential term limit in 2015, have now entrenched term limits in their respective national constitutions.

Strengthened Democratic Institutions

A major challenge of democracy in West Africa is the excessive power wielded by the executive arm and flawed checks and balances exerted on this autocratic tendency. Strong democratic institutions exert checks on the exercise of power by the executive. For democracies’ superior performance, three overarching qualities stand out: shared power, openness, and capacity for self-correction.[17] Independence and effective functioning of the judiciary, parliament, civil society, and free press with inclusive political participation and political equality are critical norms that need to be further entrenched in the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance. In addition, ECOWAS’ legal instruments should enhance parliamentary immunity and basic functions in political governance processes to deter undemocratic practices in Member States. There should be regular capacity enhancement on key legislative functions (oversight, representation, and law-making) to ensure parliamentarians put national interests above personal, party, regional, or religious considerations when political reforms with the potential of tenure elongation are brought to the fore. In this regard, the tension between party loyalty and partisanship should be resolved in favour of bipartisanship and patriotism in legislative practice and debate, particularly on matters of constitutional reform for undemocratic retention of power by incumbents.

Democratic Support

ECOWAS’ support in terms of democratic strengthening, electoral assistance, and election observation have deepened electoral integrity, political participation, and electoral security in Member States. But this support needs to be expanded to incorporate new initiatives to enhance constitutionalism, participation, pluralism, and human rights. Specifically, in view of structural conflict orchestrated by the application of national constitutions, ECOWAS should facilitate the development of a Model Constitution that will be hinged on the Constitutional Convergence Principles and other international best practices. It should also reflect international standards on electoral management and administration, leadership succession, party registration, democratic and good governance norms, among others. In addition, given the controversies surrounding parrainage across Member States, ECOWAS should facilitate the development of regional guidelines on parrainage. These guidelines should comprise harmonised principles that govern the application of parrainage with particular emphasis on domestic political and socio-cultural context of States without prejudice to human rights, the rule of law, participation, and electoral quality.

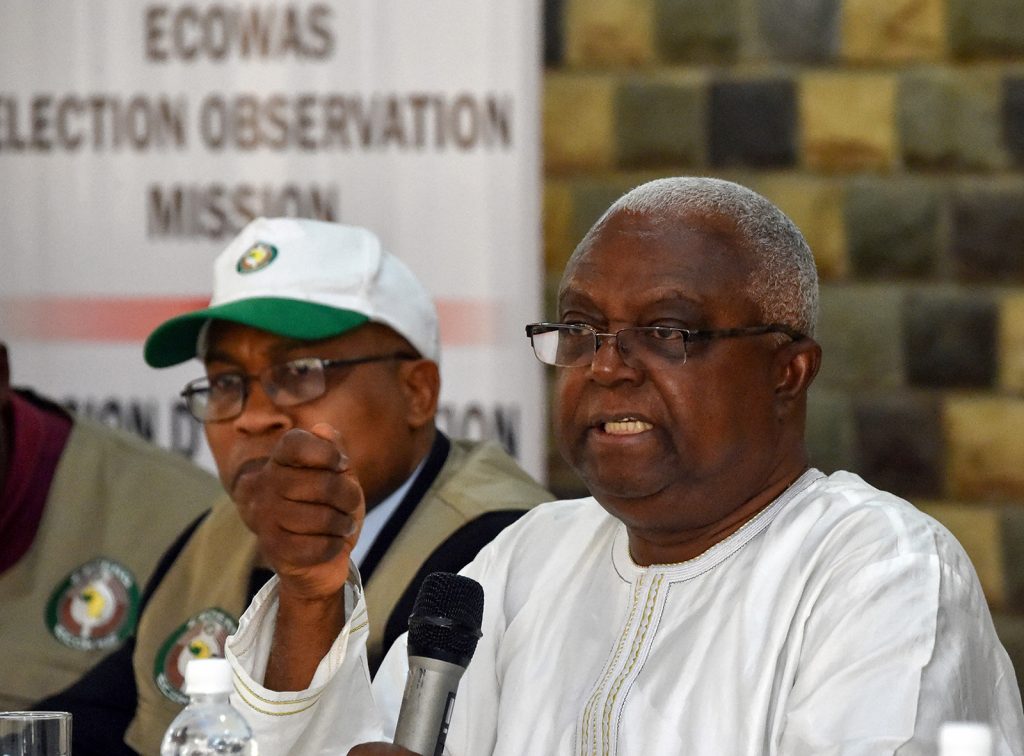

Similarly, ECOWAS needs to maximise its engagement with past Heads of State and Governments to promote peaceful power transfer and after-office security. The ECOWAS Commission has been engaging former Heads of State to lead ECOWAS Election Observation Missions. In other instances, former Heads of State and Government have been appointed by ECOWAS as chief mediators and facilitators. While these initiatives are commendable, their ad hoc nature and limited scope have made the efforts less effective and efficient, considering the enormous opportunities available for these personalities to enhance democratic practice and stability in the region. Besides leading Election Observation Missions, ex-presidents should be appointed as champions of democratic courses, human rights advocates, and peace ambassadors.

In addition, other non-state actors, such as the media and civil society, play a vital role in upholding norms of democratic accountability. Importantly, ECOWAS’ engagement with civil society organisations and the media should be further strengthened. The media and civil society organisations should be supported to educate the public on the implications of changes to provisions on eligibility, equal participation, and leadership succession. These actors should empower the general public to exert sustained pressure against illegal and illegitimate political reform to deter an incumbent government’s attempt to extend its stay in power undemocratically. Against this backdrop, the civic space should be consistently protected, and any attempt aimed at regulating civil society and censoring media should be resisted.

Elections are a process and not an event. ECOWAS should, therefore, refocus its democratic support towards sustainable democratic institution-building. ECOWAS should be focused on building national expertise and capacities to enhance electoral systems. This will engender national ownership of the regional initiatives to deepen institution-building. Funding partners should also align with this vision of supporting democratic institutions to deliver credible and democratic elections.

Reforming Electoral Processes

Political reform can either aid in the consolidation of democratic institutions and processes or create vulnerabilities for instability and violent conflict. The interplay between reforms and their consequences is central to whether such reforms will fuel instability and conflict. Hence, to improve political stability in West Africa, ECOWAS must set certain principles to guide Member States in enacting political reforms. Principally, political reforms should be conducted in compliance with democratic tenets, while ensuring a maximum level of respect for fundamental human rights, accountability and sustainability. Democratic tenets for political reform should promote consensus, inclusivity, credibility and transparency as key principles guiding the process and implementation.

The question of consensus should be addressed alongside the timeline within which political reforms relating to political leadership, term limit, and inclusivity can be adopted. This is important because the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance bans any electoral reform six months before the holding of an election, except when such reform is agreed upon by the majority of political actors. The possibility of amendments to the constitution by an ostensibly ambitious incumbent government has opened the way for abuse. Clearly, the six-month period during which a reform can be accepted has outlived its importance as opportunistic politicians have undertaken reforms that resulted in undemocratic retention of power between one and four years before the holding of an election (Cote d’Ivoire in 2016, Togo in 2018, and Guinea in 2019). This does not imply banning electoral reform. Rather, ECOWAS and Member States should focus on ensuring that reforms are consensual and legitimate both in process and content.

Reaching consensus on political reforms has been difficult across Member States largely due to corruption and intimidation. While consensus does not equate with unanimity, the reductionist conception of pluralism has restricted the scope of actors required to consent to political reforms. Attaining consensus on political reforms should be hinged upon broad-based pluralism of stakeholders, including civil society organisations, traditional and socio-cultural authorities, trade unions, and professional bodies. This approach to political reforms accords more legitimacy and sustainability to the reforms. The process and outcome of political reforms are important to enhance the credibility of the reform.

Enforcement Mechanisms

The Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance and other relevant legal and normative instruments commit Member States to constitutionalism, the rule of law, and human rights. This provides the basis for developing robust enforcement mechanisms to ensure the effective application and protection of these norms. Sanctions are contained in the Protocol to make Member States comply with democratic and human rights principles. Lessons learnt from sanction application shows that they are less appropriate to address emerging political reforms that favour presidential term extension and/or policies that exclude opposition or discriminate against women and youth. In strengthening the sanction regime, ECOWAS should consider the progressive application of suspension of electoral support, including election observation boycotts, trial and ban of perpetrators from contesting elections, and non-recognition of governments emanating from such elections.

Conclusion

The quality of democracies in the ECOWAS region is declining, driven by disrespect for constitutionalism, illegitimate and exclusionary electoral policies, weakened checks and balances, shrinking civic spaces, and increasing gender inequality. In this context, the implication of democracy backsliding in West Africa may lead to a resurgence in coups d’état, regional instability, and negative effects on international peace and security. ECOWAS’ democracy and governance assistance is increasingly difficult to execute, but ever more crucial to nurturing and consolidating legitimate democratic gains recorded over the years.

Given the significant investment that ECOWAS and other domestic, regional and international actors make in West Africa to promote democracy and mitigate conflict, it is important for the regional body to recalibrate its efforts towards entrenching adherence to constitutionalism, strengthening democratic institutions, refocusing democratic support, supporting efficient enforcement mechanisms, and reinforcing civil society.

Mubin Adewumi Bakare is a Consultant at the ECOWAS Commission. He is also a doctoral student at the Department of Defence and Strategic Studies, Nigeria Defence Academy, Kaduna, Nigeria.

Endnotes

[1] Repucci, Sarah and Slipowitz, Amy (2021) ‘Freedom in the World Report 2021’, Freedom House, Available at: <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege> [Accessed 14 August 2021].

[2] The Economist (2020) ‘Democracy Index: Global Democracy Has A Very Bad Year’, Available at: <https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/02/02/global-democracy-has-a-very-bad-year> [Accessed 15 August 2021].

[3] Osori, Ayisha (2021) ‘How Tenure Elongation and a Lack of Term Limits Weaken the Integrity of Elections in Africa’, Mail and Guardian, 23 March, Available at: <https://mg.co.za/africa/2021-03-23-how-tenure-elongation-and-a-lack-of-term-limits-weakens-the-integrity-of-elections-in-africa> [Accessed 10 July 2021].

[4] Bado, Kangnikoe (2019) ‘Togo’s Continuing Constitutional Crisis and ECOWAS’s Failed Mediation Effort’, ConstitutionNet, Available at: <https://constitutionnet.org/news/togos-continuing-constitutional-crisis-and-ecowass-failed-mediation-effort> [Accessed 11 July 2021].

[5] Africa News (2020) ‘COVID-19 Takes its Toll on African Economy’, Africa News, 30 December, Available at: <https://www.africanews.com/2020/12/30/covid-19-takes-its-toll-on-african-economy> [Accessed 15 August 2021].

[6] Brown, Odigie (2017) ‘Regional Organisations’ Support to National Dialogue Processes’, Conflict Trends, 3(17), Available at: <https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/regional-organisations-support-national-dialogue-process> [Accessed 11 July 2021]; Brown, Odigie (2020) ‘ECOWAS Mediation in Togo 2017/2018 Political Crisis: Feats, Deadlock and Lessons’, African Peacebuilding Network, Working Paper No. 27; Mubin, Bakare (2020) ‘Threats to Credible Elections in Cote d’Ivoire: An Overview’, Centre for Democracy and Development, Available at: <https://cddelibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/threats-to-credible-elections-in-cote-d’ivoire-2.pdf> [Accessed 20 July 2021].

[7] Olukoshi, Adebayo (2018) ‘Political Reforms and Link with Governance at a UNOWAS Regional Colloquium on Challenges and Prospects of Political Reforms in West Africa’, Abidjan, 26-27 March.

[8] Mamdani, Mahmood (1992) ‘Africa: Democratic Theory and Democratic Struggles,’ Economic and Political Weekly, 27(41), 2228–32. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org/stable/4398993> [Accessed 14 September 2021].

[9] Olukoshi, Adebayo (2018) op. cit.

[10] Boucher, Alix (2020) ‘Defusing the Political Crisis in Guinea’, Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, Available at: <https://africacenter.org/spotlight/defusing-political-crisis-guinea> [Accessed 19 July 2021].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Federation Internationale Pour les Droits Humains (2020) ‘Communique – Guinée: Les acquis de la démocratisation de 2010 remis en cause’, Available at: <https://www.fidh.org/fr/regions/afrique/guinee-conakry/guinee-les-acquis-de-la-democratisation-de-2010-remis-en-cause> [Accessed 19 June 2021].

[14] Government of Senegal (2018) ‘Loi No. 2018-22 du 4 Juillet 2018 portant revision du Code Electorale’, Available at: <https://www.sec.gouv.sn/loi-n%C2%B0-2018-22-du-04-juillet-2018-portant-r%C3%A9vision-du-code-%C3%A9lectoral> [Accessed 11 May 2021].

[15] ECOWAS Community Court of Justice (2018) ‘Judgement on USL vs Republic of Senegal – ECW/CCJ/APP/59/18’, Available at:<http://prod.courtecowas.org/2021/04/29/court-judgment-mandates-senegal-to-remove-obstacles-to-free-participation-in-countrys-elections> [Accessed 1 July 2021].

[16] Siegle, Joseph and Cook, Candace (2020) ‘Circumvention of Term Limits Weakens Governance in Africa’, African Centre for Strategic Studies, Available at: <https://africacenter.org/spotlight/circumvention-of-term-limits-weakens-governance-in-africa> [Accessed 1 July 2021].

[17] Halperin, Morton; Siegle, Joseph; and Weinstein, Michael (2010) The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace. New York: Routledge, pp. 71–78.