Introduction

On 8 May 2019, South Africans went to the polls to elect a government of their choice. This election was South Africa’s sixth since the country held its first democratic election in 1994. Twenty-five years later, questions are being asked about whether the ruling party has delivered on its electoral promises since its victory in the April 1994 election. These and other questions have arisen due to the country’s socio-economic challenges such as increasing youth unemployment, massive public-private sector corruption and deep-seated inequality. These challenges have resulted in renewed calls for political alternatives. This search for political alternatives is evidenced by a significant increase in the number of new political parties that have formed since 1994 – over 40 political parties contested the May 2019 election in various parts of the country. In spite of the growth in the number of political parties, the question that has not generated sufficient debate in either political and policy circles is the role of the youth in South Africa’s democracy, and in electoral processes in particular.

This article reports on the findings of a socio-anthropological research study on society, politics and electoral processes in South Africa, conducted as part of an international research project titled Re-examining Elections after African Experiences.1 The article provides an analysis on what the electoral process and voting specifically means to South African youth.

Theoretical Framework

Arnstein2 advanced the Ladder of Citizen Participation (LCP) theory to reflect on the marginalisation of the voices of minority groups in the United States (US), and how the marginalisation of these voices affected the quality and vibrancy of democracy in the US. The theory holds that representation and participation of all groups in society is key and fundamental to the existence of a vibrant democracy. In other words, a vibrant democracy requires that all social groups have a voice in how they wish to be governed, while institutions tasked with the exercise of this civic duty must provide spaces that allow for full and effective participation.

Arnstein highlights two important aspects that are essential in our analysis of the electoral process in South Africa. These are citizen participation as citizen power and empty ritual. Citizen power implies that the citizenry is given full and adequate support to participate in democratic processes, including electing public officials. Empty ritual describes situations where citizen participation is skewed in favour of certain constituents. In this article, we consider voting as a participative process that gives citizens the power to influence political decisions. The ability of the electorate to participate in electoral processes therefore ideally becomes an essential process that ensures a vibrant democracy. In addition to the electorate seeing themselves as crucial partners in the building of progressive society, in a vibrant democracy the electorate usually has power to control the behaviour of those they elect. The implication here is that citizen engagement through voting processes gives the electorate the ability and power to decide who gets to govern. However, if the process of participation is skewed and twisted to benefit only a select group, then participation becomes an empty ritual. Under these circumstances, the electorate’s disenchantment with political processes becomes a threat to democracy. This article outlines various political factors that result in electoral processes being rendered empty rituals from the perspective of the youth in South Africa.

Across the world, the actual casting of votes on polling day is considered one of the most effective ways to engage citizens in political and electoral processes. Scholars3 note that although there has been a noticeable decrease in voter turnout in South African elections since 1994, the poor and disjointed participation by the youth in particular is concerning. A vibrant democracy anywhere in the world depends on active and effective participation by the electorate.

Methodology

This article focuses on the findings of an electoral research project conducted in various provinces across South Africa between January and June 2019. The research is part of an international socio-anthropological study on society, politics and electoral processes undertaken by the Institut des Mondes Africains, a research institute based in France. We adopted a purely qualitative methodology and the data is analysed thematically. The data collection process was divided into two phases. The first phase was the construction of a data archive, and involved the collection and analysis of information about the electoral process in the country. Information collected for archival work was gleaned from newspapers, journal articles, television and radio interviews, and opinion editorials.

The second phase, which forms the basis of this article, involved the research team conducting primary research, largely through interviews and observation. This was conducted before the election, on the voting day and after the election, in the same areas. Observation was employed on the election day to complement data obtained through other sources. Semi-structured and in-depth interviews were conducted with voters, political party representatives and important stakeholders, during and after the election. This article reports on findings as they relate to youth involvement in the electoral process in South Africa. Arnstein’s theory is an efficient tool to examine the role of youth within the broader democratisation process in South Africa.

Youth Apathy in the South African Elections

There is increasing evidence that in the 21st century, youth across the globe are increasingly becoming disenchanted with political processes, and electoral processes in particular. Most recent studies show that in countries including the US and the United Kingdom (UK), there is a noticeable increase in the number of young citizens who have consciously and intentionally distanced themselves from political activities and electoral processes since the late 1990s.4 A study conducted by Hill and Rutledge-Prior5 in Australia shows that the country experiences a high number of intentional, informal voting (spoilt ballots), and youth are usually associated with this behaviour. In some contexts, this behaviour is associated with “protest voting” – a situation where the electorate intentionally spoils ballots to express their displeasure with governing parties, or simply to punish political parties they believe are failing them.

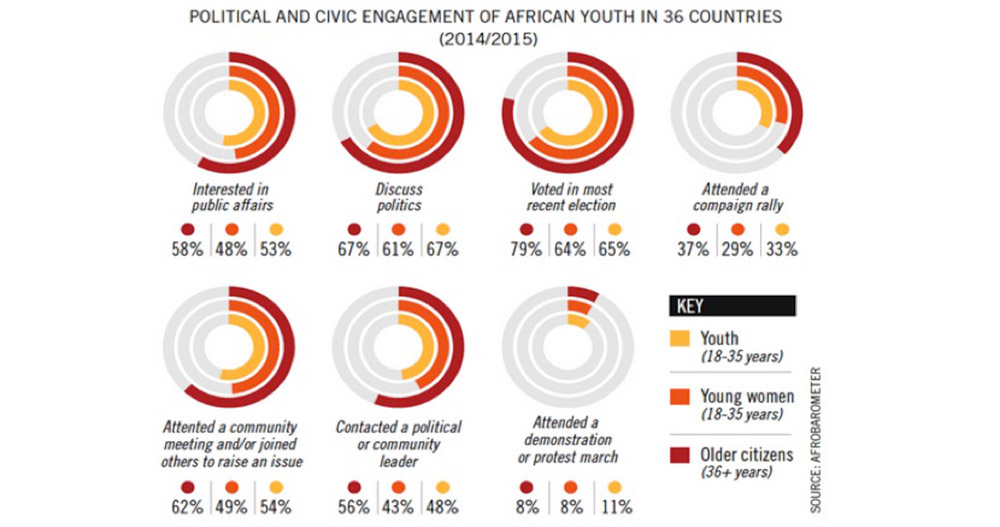

A survey6 of 36 African countries by Afrobarometer – a pan-African, non-partisan survey project that measures citizen attitudes on democracy, governance, the economy and civil society – notes that African youth exhibit the lowest levels of political and civic engagement compared with other age groups, as evident in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Political and civic engagement of African youth in 36 countries 2014/157

Although the youth discussed politics and showed a higher interest in political and public affairs, they were less likely to participate in an actual election. We found this to be the case with the youth we interacted with during our research.

Some reasons that have been provided to explain voter apathy and political disengagement, particularly by youth, include a lack of political party membership and low levels of political participation, a disinterest in electoral politics, high levels of cynicism about politics and a low level of confidence in the country’s democracy. These factors were found to hold true in a survey conducted by the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex in the UK.8 In some contexts, it is because most young citizens feel political parties do not have their concerns and interests at heart. Our findings show that some of these factors partly explain why youth in South Africa exhibit low levels of conventional political engagement and participation.

The general election in 2014 was noted for being the first national election in which young South Africans, mostly those born after 1994 (the “born-frees”) were expected to participate. Malila9 argues that the participation of youth in the election in 2014 was critical for two reasons. First, it remained a formal and legalistic way for people who have come of age politically to have their voices heard. Second, it was the first opportunity for this generation of South Africans to establish their political identity as active and engaged citizens, to fulfil their constitutional obligations and exercise their democratic and civic rights. However, the low voter turnout in that election, particularly among youth, was a wake-up call for South Africa. Analysts10 suggest that vote casting on polling day is only a part of a bigger and broader democratisation process. The point is that political participation cannot be reduced to vote casting alone. There are many ways to participate in political and electoral processes – for example, attending community meetings or writing to and contacting an elected official.

Emerging research on political and civic participation among youth in South Africa points to the fact that youth find formal political processes not only frustrating and alienating but also less likely to yield desired results.11 It is not surprising, therefore, that young citizens in South Africa are often apathetic and feel marginalised, sceptical and distrustful of political parties, and politicians in particular. These factors hinder their full, effective and active participation in political and electoral processes. Furthermore, young people often feel disempowered by the same political actors who should be empowering them.12 Our research team also observed that on election day, the number of youth at polling stations was lower compared to other age groups.

However, some scholars13 warn that youth voter apathy, in particular, must not be seen as general apathy to political participation. They argue that although youth participation in political and electoral processes has waned over the years, civic engagement in democratic processes remains vibrant in communities, university campuses and alternative platforms such as social media. Youth in South Africa remain actively engaged in various significant governance processes such as service delivery protests, community demonstrations and protests on university campuses. Although not necessarily new, this form of “unconventional engagement”, to use Dalton’s14 phrase, addresses various sociopolitical and economic issues that concern youth. A good example is the #FeesMustFall movement15 that gripped university campuses across South Africa in 2015, leading to policy shifts on the part of government on higher education financing.

Hills and Rutledge-Prior and Malila16 argue that although youth participation in legalistic and formalistic ways has declined – for example, in general and municipal elections, youth remain socially and politically engaged through other means such as social media. In the past, opinions shared and discussed on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have fundamentally transformed the social and political landscape in South Africa – for example, the #FeesMustFall protests. These alternative spaces offer conducive platforms for political organising. The importance of these platforms will become more crucial as more people get access to social media tools.

Political Fatalism and Voter Apathy among Youth in South Africa: Findings

The Electoral Act 73 of 1998 (S. 1) of the Republic of South Africa17 states:

Any South African in possession of an identity document has the right to register as a voter. Where a citizen is ordinarily resident outside the Republic, she/he must in addition to the identity document produce a valid South African passport. A person of 16 years or older may apply for registration but, if the application is successful, the applicant’s name may only be placed on the voter’s roll once the applicant reaches the age of 18.

South Africa’s National Youth Commission (NYC) Act of 1996 defines youth as persons aged between 15 and 35. The Act asserts that the essence of this categorisation is that many of the older youth, most of whom were disadvantaged by their role in the struggle against apartheid, needed to be included in youth development initiatives.18 However, our research exclusively focused on the 18–35 year age group.

An Unresponsive Political System

Mattes19 notes how South Africa’s transition from an authoritarian regime to a democratic dispensation was stalled by a paradoxical political situation that prevented the effective consolidation of democracy. He further posits that a stagnating economy, abetted by high levels of inequality, threatened the transition to democracy. Many factors – including but not limited to high unemployment (particularly among the youth); high poverty among blacks; poor and, in some instances, non-existent service delivery; and a corrupt and self-interested political elite – seem to have convinced the youth that voting is simply a waste of time. Poor governance problems have resulted in low levels of confidence in the ability of the political system to curb vices such as corruption. Governance problems are major disincentives to political participation. In our research, a participant explained the following:

The leaders are corrupt and only use voting to endorse themselves into office so that they can continue looting. How then can I participate in such a scam? I am educated but I cannot land any job with my degree, simply because some politicians are too busy thinking of how they can keep themselves rich, forgetting our [youth] struggles. There is no future for young people unless we decide to do something about it, but not by voting, it will not change anything.20

This view was widely shared among a number of young citizens. It confirms conclusions by Mattes and Richmond21 who, in 2013, found that South Africa’s youth are generally seen as disengaged from conventional forms of political participation such as voting and contacting elected officials, yet they are also seen to be disproportionately more likely to engage in protests and political violence. Interestingly, some party representatives saw this disengagement by young people as a betrayal of the youth of previous generations, who were involved in the Soweto Uprising22 in 1976 and, later, the street protests of the 1980s.

Low levels of political engagement do not necessarily mean that the youth are completely disengaged from political and civic matters. We agree with Mattes and Richmond,23 who argue that cognitive engagement – that is, the degree to which people are interested in politics and discuss it with family and friends – remains relatively high, especially among youth. The youth of South Africa seemed well versed with the political climate in the country. In fact, some of their predictions were insightful, especially once election results were officially announced a few days later:

Mmmmm, you see, we have a very complex political situation in South Africa. I hate to tell you this, my brother, but the ANC [African National Congress] will win. They have a huge following in rural areas and key metros like Gauteng and KZN. I don’t think the alleged factional fights within the ruling party will cost them the election. In any case, I expect them to get anything above 55%. The EFF are good but they don’t stand a chance. The ANC is the people’s liberator. Although I won’t be voting in this election, if I were forced to, I would go with the ANC.

When questioned further on why he would not be voting, the participant’s response was:

Why should I vote people who don’t care about my well-being? I enjoy talking politics, but I am not the person to waste my time nourishing a system that doesn’t recognise my self-worth. I have better things to do than wait for a political saviour.

This response is characteristic of the mistrust that exists between politicians and the electorate, on the one hand, and between the younger generation and the older generation, on the other. Young people generally place blame on the political system and see it as responsible for their misfortunes. Malila24 and others argue that an unsupportive political system is probably the biggest threat to youth participation in modern-day politics and political processes. Mattes and Richmond25 also confirm that youth apathy and political fatalism have increased over the years due to poor governance, the generational factor and general disinterest in political matters.

Our research found that young people are more comfortable engaging in other forms of activism, such as service delivery protests and protests at university campuses, which have become commonplace occurrences in South Africa. The youth see these protests as a platform to express their anger and disgust with public sector corruption, poor governance and poor service. However, as rightfully noted by Galton,26 these forms of activism usually fall outside the purview of the law, and often turn out to be violent and chaotic. This militant approach was justified by another participant as necessary to “get them to hear us”. She noted the following:

There is no way they will listen to us if we go and sit with them in air-conditioned boardrooms. After the boardroom, we are back to square one. We do not condone violence, but sometimes it’s the only way to get them to listen.

Economic Challenges and Youth Tokenism

Economic challenges were also cited as major disincentives inhibiting the youth’s effective participation in electoral processes. When asked about his take of the electoral process, a participant had the following to say:

I did not register to vote, nor did I feel the urge to take part in the electoral process. You see, my brother, the nature of my job pays according to the effort I put into it. My boss does not care if I voted or not; he wants me to meet his daily target. I cannot afford to lose money because of elections which will not change my situation. I voted in the past, but nothing has changed, I am a little worse off today than I was 10 years ago. This thing simply doesn’t work!

Even though he did not register to vote, the participant affirmed his undying loyalty for the ANC ruling party and expressed his optimism that the party would emerge victorious. He recalled how his late father was a veteran of the ANC and a key member of the party’s armed liberation wing. However, he still expressed reservations with the ANC, noting:

The ANC I grew up knowing is no longer the same ANC. Too many corruption scandals. It has soiled the party.

It is important to highlight that despite the youth demographic advantage, the majority expressed low confidence in electoral systems and political processes. It was also interesting that some young people seemed prepared to sacrifice democracy for a government that could promote development, create jobs and improve service delivery, as noted by a participant:

I don’t care about democracy. I only care about my well-being and that of my family. If democracy cannot provide jobs and a decent living, what’s the point?

Although very few identified with political parties, those who did had reasons for doing so – for example, familial political ties. Others formed political identities based on their dislike for other political parties. Political processes driven by dislike for the other party results in polarisation, with severe consequences. There is a need for voter education that invests in ideological politics rather than personalities. This is a process where political education and communication evolves from simply expressing why one candidate is better than the other to explaining what one should consider in selecting a preferred candidate. This is one way to mitigate political polarisation while minimising voter apathy, particularly among the youth.

Conclusion

While South Africa remains a democratic model in the region and the continent more broadly, the realisation that the country’s young population has lost faith in political systems, and electoral processes in particular, is concerning and does not bode well for democracy. Political parties and electoral bodies must strive to create conditions that allow for the effective participation of all age groups in politics, including young citizens. The rise to prominence of Robert (“Bobi Wine”) Kyagulanyi Ssentamu in Uganda, Nelson Chamisa in Zimbabwe and Julius Malema in South Africa is confirmation that young people are beginning to question the status quo and are pushing the limits of old systems. These dynamics demonstrate how generational politics can shift the political landscape and possibly bring countries within tipping points of new crises.

Endnotes

- We are grateful to Pietro di Serego for reviewing and providing insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

- The data gathered in this research project is accessible through the EleQta platform at <www.eleqta.org>

- Arnstein, Sherry R. (1969) A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35 (4), pp. 216–224.

- Malila, Vanessa (2016) Voting Void? Young South Africans, Elections and the Media. Communication, 42 (2), pp. 170–190. See also Oyedemi, Toks and Mahlatji, Destine (2016) The Born-free Non-voting Youth: A Study of Voter Apathy Among a Selected Cohort of South African Youth. Politikon, 43 (3), pp. 311–323.

- Ibid.

- Hill, Lisa and Rutledge-Prior, Serrin (2016) Young People and Intentional Informal Voting in Australia. Journal of Political Science, 51 (3), pp. 400–417.

- Lekalake, Rorisang and Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2016) ‘Does Less Engaged Mean Less Empowered? Political Participation Lags among African Youth, Especially Women’, Afrobarometer, Policy Paper 34, Available at: <http://afrobarometer.org/publications/youth-day-2016> [Accessed 15 July 2019].

- Ibid.

- BBC (2014) ‘Most Young People Lack Interest in Politics – Official Survey’, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-26271935> [Accessed 15 July 2019].

- Malila, Vanessa (2016), op. cit.

- Malila, Vanessa (2016), op. cit. See also Mattes, Robert (2012) The ‘Born-frees’: The Prospects for Generational Change in Post-apartheid South Africa. Australian Journal of Political Science, 47 (1), pp. 133–153.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Hill, Lisa and Rutledge-Prior, Serrin (2016), op. cit.

- Dalton, Russell (2009) The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation is Reshaping American Politics. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press.

- #FeesMustFall was a student-led protest movement that began in mid-October 2015 in South Africa. The goals of the movement were to stop increases in student fees and to increase government funding of universities.

- Hill, Lisa and Rutledge-Prior, Serrin (2016) op. cit. See also Malila, Vanessa (2016) op. cit.

- Electoral Act 73 of 1998, Juta and Company Ltd. Available at: <http://www.elections.org.za/content/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=989> [Accessed 15 July 2019].

- Government of South Africa Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) (2014) Background Paper: Youth. Twenty-year Review 1994-2014. Pretoria.

- Mattes, Robert (2012) op. cit.

- The data gathered in the EleQta platform can be accessed at<www.eleqta.org>

- Mattes, Robert and Richmond, Samantha (2015) ‘Are South Africa’s Youth Really a “Ticking Time Bomb?”’, Afrobarometer, Working Paper No. 152, Available at: <http://afrobarometer.org/sites/default/files/publications/Working%20paper/AfropaperNo152.pdf> [Accessed 18 July 2019].

- The Soweto Uprisings were a series of demonstrations and protests led by black schoolchildren in South Africa that began on the morning of 16 June 1976.

- Ibid.

- Malila, Vanessa (2016) op. cit.

- Mattes, Robert and Richmond, Samantha (2015) op. cit.

- Dalton, Russell (2009) op. cit.