Introduction

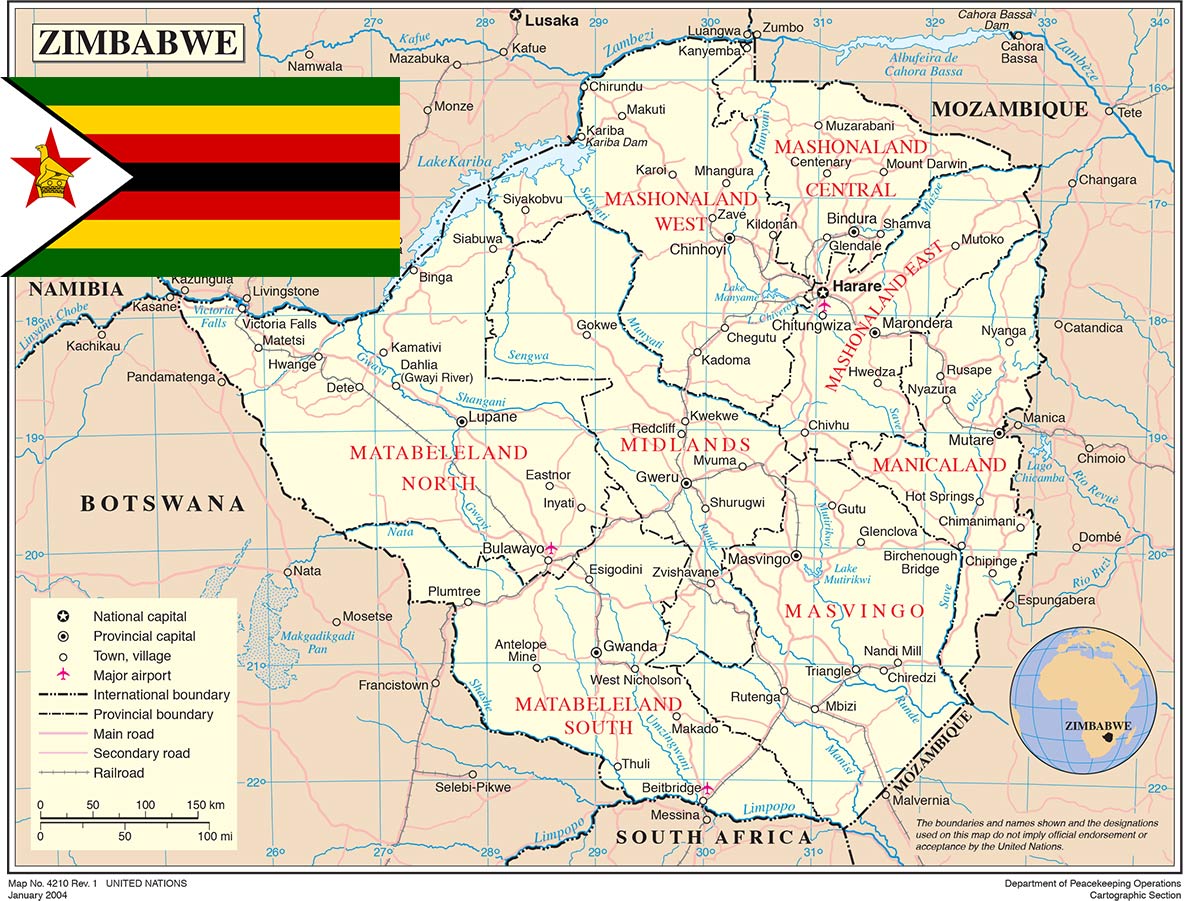

Zimbabwe’s transition to a peaceful nation remains at a crossroads, as the government has failed to put in place viable transitional justice mechanisms. The southern African country experienced a series of conflict episodes before and after its independence in 1980, but there has never been a viable nationally adopted process that facilitates meaningful national healing, reconciliation and integration. Zimbabwe adopted a new constitution in 2013, providing for the establishment of a National Peace and Reconciliation Commission (NPRC) that marks the government’s interests to address past conflicts and maps a new path for peacebuilding. Essentially, conversations and interventions on transitional justice, truth-telling, reconciliation, justice and restoration are already taking shape. However, within the current transitional justice discourse among civil society actors, the government and citizens, the notion of “amnesty” as part of the broad transition dialogue remains absent. This article therefore attempts to explore the place for amnesty in Zimbabwe’s transitional justice process.

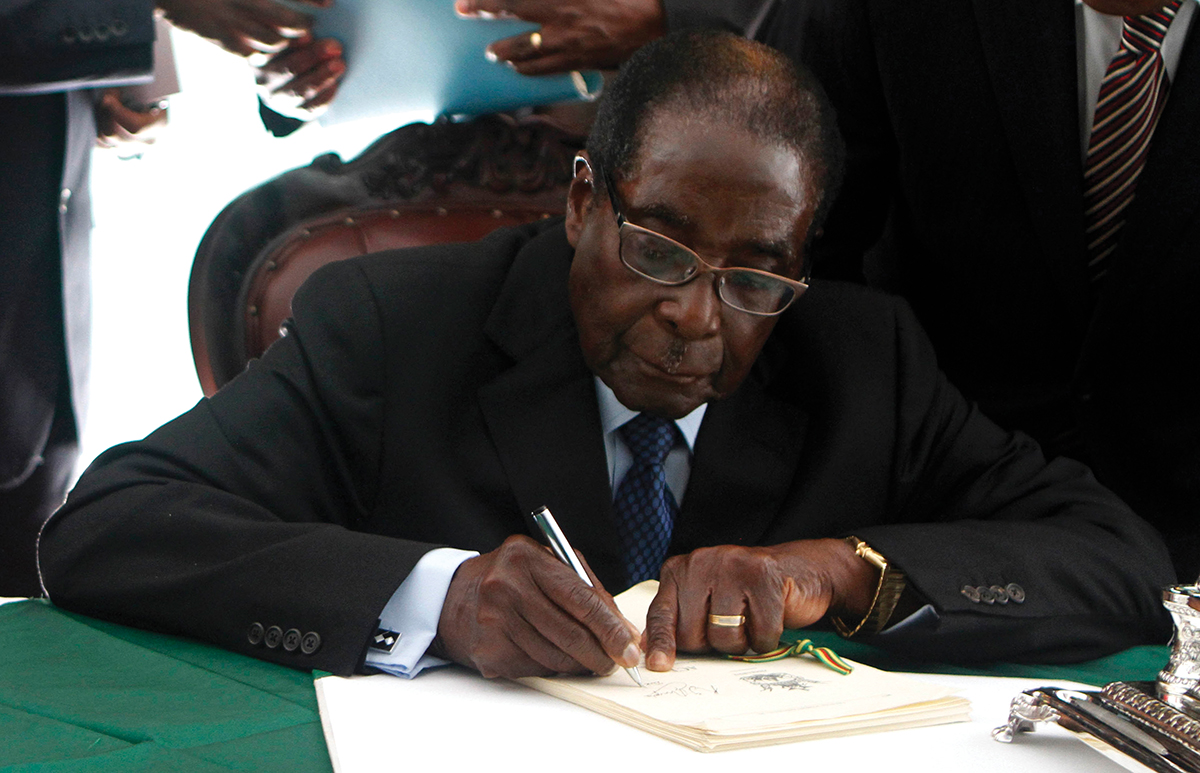

Following the publication of the NPRC Bill on 18 December 2015, and the subsequent swearing in of NPRC members by President Robert Mugabe in early 2016, the process of national healing and reconciliation can now officially begin in Zimbabwe. The environment in which the process is taking place is, however, replete with stumbling blocks and drawbacks – chief of which is political interference and a glut in funding. Thus, much of the “transitional justice” at present is in the form of discussion and dialogue, especially among civil society organisations and opposition political parties. Of concern in these dialogues is the absence of amnesty as part of the transitional justice process. Currently, much of the dialogue places emphasis on truth-telling, criminal justice, reparations and reconciliation. Commenting on the National Transitional Justice Working Group (NTJWG), which was established to coordinate the process, one observer remarked:

The notion of amnesty in exchange for truth-telling was rejected by a large majority of NGOs, with the exception of church-based groups, who however conceded that their constituencies resisted amnesty.1

Yet amnesty is a pivotal pillar of transitional justice – as it has been in South Africa, where the truth was exchanged for amnesty from prosecution.2 It is this incentive that encourages the telling of truth, thereby leading to reconciliation. There is no use for perpetrators to voluntarily come forth and tell what they did if they do not hope to get anything out of it, or if they will be prosecuted or subjected to punishment.

At the moment, the transitional justice process in Zimbabwe is a political minefield as there has not been any shift in power; hence, there cannot be meaningful transitional justice without transition. It is therefore incumbent upon those who seek to address the past to cajole and persuade perpetrators to come forward. Admittedly, this cannot be expected to commence easily, given that those implicated in gross human rights violations would want unconditional amnesty without truth-telling.3

Conceptualising Amnesty

Amnesty refers to the act of forgiving someone or a class of persons for past offences. The pardoning is particularly done for political criminals, and can be granted either before trial or after conviction. While the term can be applied in a variety of settings, amnesty within the context of transitional justice has traditionally been used as a political tool of compromise and reunion following war and conflict. The emergence of amnesty is a result of countries absolving those people involved in crimes against humanity and gross human rights abuse to avoid their prosecution, as a way of encouraging the restoration of democracy.4 Facilitating amnesty can be a necessity, especially under circumstances where the incumbent political leaders and hardliners are holding back transitional justice for fear of retribution, arrests and loss of material benefits. This means amnesty in itself can predictably curb repression from incumbent political leaders and hardliners afraid of retribution.

Amnesty can be distinguished from other pardons. A pardon is a tool that exempts a convicted criminal or criminals from serving his, her or their sentence(s), in whole or in part, without expunging the underlying conviction by an Official Act.5 Amnesty, on the other hand, refers to the broader transitional justice framework – a set of judicial and non-judicial measures targeted at addressing the legacies of human rights violations.

In Zimbabwe, amnesty has previously been applied through the Amnesty (General Pardon) Act [Chapter 9.03]. This Act, which authorises discontinuance of prosecution, is popularly known as the presidential pardon, as it is exercised by the president.6 The Amnesty (General Pardon) Act authorises pardoning of any offence committed in good faith before or after 1980, and any other offences specified in the Act. Whilst Zimbabwe had several declarations of amnesties that benefited perpetrators of gross human rights violations, those processes have neither promoted transitional justice, national healing and reconciliation nor proved to be developmentally democratic. Alex Magaisa observes that Zimbabwe’s presidential amnesties rewarded villains and perpetuated violence, gross human rights violations and unbearable political corruption.7 For example, security forces who presided over the massacre of over 20 000 people in the Matabeleland and Midlands regions of Zimbabwe were granted amnesty in 1988 through Clemency Order No. 1 of 1988.

Whether democracy and sustainable peace in Zimbabwe can be reached through amnesty requires a thorough interrogation. Controversially, amnesty can be viewed as the protection of those who murder, torture and perpetuate human rights violations. In Afghanistan, there was an outcry when its amnesty law was established. Citizens complained that it did not benefit the nation, but rather protected and benefited those who had committed war crimes, and actually inspired others to commit the same kind of crimes. In South Africa, amnesty played a significant part in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), but the majority of the black population who suffered under apartheid remain disillusioned.

Amnesty is not a silver bullet or magic wand to promote transitional justice. Instead, it can generate destabilising dissent and, to a greater extent, defeat the purpose of justice and the justice delivery system. To make matters worse, amnesty neither guarantees an end to impunity, gross human rights violations and torture nor the non-recurrence of such violations.

While amnesty is practised by states, the Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC) prohibits countries from supporting amnesty for crimes against humanity (international crimes, including genocide and war crimes). This suggests that within the ambit of international law, some offenders should face the full wrath of the law, regardless of the benefits that may come with the amnesty exercise.

The Practice of Amnesty in Zimbabwe

The granting of amnesty in Zimbabwean history is not new. However, what is uncommon are the motives behind each general pardon granted. From the colonial era to independent Zimbabwe, amnesties – also known as presidential pardons, prerogatives of mercy or presidential clemency – have been pronounced several times: 1975, 1979/80, 1988, 1990, 1993, 1996, 2000, 2001 and 2014.

Amnesties in Zimbabwe8

| Year | Amnesty |

| 1975 | The Indemnity and Compensation Act granted amnesty to the police force, civil service and Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) members for offences committed in the past (in retrospect) and for those anticipated |

| 1979/80 | Amnesty Ordinances of 1979 and 1980 were granted by the transitional government at the sealing of the Lancaster House Agreement. |

| 1988 | General Notice (GN) 257A/1988 granted amnesty to “dissidents”, collaborators and members of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU).9 |

| 1990 | General amnesty, repeating GN257A/88 to include the state’s uniformed forces, who had been responsible for Gukurahundi in the Matabeleland and Midlands provinces in Zimbabwe from 1982 to 1987. Gukurahundi is the name given to the bloody military repression of opposition to the government immediately after Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980. This repression led to over 20 000 deaths, affecting mainly the Ndebele tribe in Zimbabwe’s Midlands and southern provinces. |

| 1993 | GN111C was a general amnesty for people arrested before 31 March 1980 and prisoners serving less than 12 months. |

| 1996 | GN362A was a general amnesty for life sentences before 31 January 1981, infanticide offenders and determinate sentences. |

| 2000 | GN457A was a general amnesty for politically motivated crimes (liability pardon and remission of sentences). However, the names of those pardoned were never published. |

| 2014 | Close to 2 000 inmates were granted pardon – reportedly due to hunger and service delivery pressures in the country’s prisons. |

It is important to note that the peace which Zimbabwe enjoyed between 1980 and 1998 was due to two amnesties: that contained in the Lancaster House Agreement,10 and that which marked cessation of hostilities between the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and ZAPU and culminated in the signing of the Unity Accord in December 1987. The Unity Accord led to the merging of ZANU and ZAPU to establish the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF). These amnesties were clear post-independence political exonerations. Unfortunately, the absolutions technically united the political elites, leaving the grassroots divided.

The amnesty in 2000 (GN457A) benefited ZANU-PF supporters who were implicated in unleashing politically motivated violence, arson, the burning of homes and the intimidation of opposition supporters.11 This amnesty could have been perceived as a sign that the country was shielding human rights violators from prosecution. Such insulation from legal and criminal justice has consequently further exacerbated the culture of violence in Zimbabwe. Geoff Feltoe agrees that the practice of amnesty in Zimbabwe has been partisan and has engendered a culture of impunity.12

Violence also increased with the implementation of the fast-track land reform policy, where many white farmers and their workers were killed, tortured and harassed. Few of these instigators of violence were tried and charged, as most of them were granted amnesty under the Clemency Order of 2000.From this perspective, the practice of amnesty can be less attractive if supporters of one hegemonic political party (such as ZANU-PF) enjoys state amnesty without contrition. Thus, any future partisan amnesty will unequivocally frustrate genuine and noble efforts towards conflict transformation and peacebuilding.

Going Forward

Transitional justice remains an outstanding item on Zimbabwe’s socio-economic and political reform agenda. The objective of exploring options for amnesty should be to “isolate the hard-line insurgents from the communities that support them ideologically, financially, or logistically”.13 Although civil society organisations reject the idea of amnesty as part of a broader framework of the transitional process, there is a need to appreciate the practical realities that can limit certain governments (such as the ZANU-PF government) in implementing specific justice measures. Therefore, as Bryan Sims writes: “The demand for criminal justice is not an absolute, but must instead be balanced with the need for peace, democracy, equitable development and the restitution of the rule of law.”14

Two options lie ahead: Zimbabwe can pursue either conditional or unconditional amnesty as part of its political transition process towards sustainable peace. Conditional amnesty simply allows pardoning when the perpetrator either offers the truth about the past or offers reparations, while unconditional amnesty allows forgiving without subjecting the beneficiaries to justice and truth-telling. Without interrogating the merits and demerits of each option, the careful use and balance of either option depends on several factors. Most importantly, the transitional and peacebuilding mechanism that Zimbabwe adopts should not close or freeze some conflict episodes without offering justice. History is littered with cases where the rights of victims to seek redress have been traded for amnesty, but without solving conflict and sociopolitical tensions. Therefore, a thoughtful, practical analysis on the validity of any possible amnesty in Zimbabwe, which places salience on the careful balance of a truth-for-amnesty formula, is a necessity.

Grassroots-driven amnesty can facilitate sustainable political transition, as it allows collective forgiveness and horizontal unity across the political divide. This means Zimbabwe can facilitate amnesty by consulting diverse stakeholders – including non-governmental organisations (NGOs)/civil society institutions, community-based and faith-based organisations, student bodies, churches, academia, individuals, independent commissions, donor agencies, traditional leadership, political parties and various ministries – to initiate dialogue along issues of amnesty, justice and reconciliation. A multi-stakeholder approach allows for collective decision-making processes that evolve with democratic principles.

Since amnesty – whether conditional or unconditional – does not guarantee non-recurrence and the repentance of the pardoned elements, there is a need to understand the desires and interests of those likely to receive amnesty. Extensive empirical research can assist political players, including policy-makers and stakeholders, to determine the feasibility of an amnesty programme in the country. However, such studies might be difficult to embark on, given the country’s current volatile and sensitive political context. A study carried out by Freedom House and the Mass Public Opinion Institute (MPOI), entitled Change and “New” Politics in Zimbabwe,15 agrees that the volatility of the Zimbabwean political landscape is not conducive for research on sensitive topics. Therefore, good security mechanisms may be of great importance if this option is taken into consideration.

Facilitating dialogue on transitional justice while deliberately placing amnesty as part of the broader transitional process can be helpful. Civic society institutions and democracy-supporting organisations working on peacebuilding and transitional justice may need to open the space for engagement and discussion with state, society, local stakeholders and global actors. This will help in articulating a shared national vision on peacebuilding and transitional justice that transcends what South African scholar, Adam Habib, terms the “dialogue of the deaf”.16 This refers to a situation where one party is not responsive to what the other is saying, leading to conflict and disengagement. In other words, civil society organisations need to utilise what John Gaventa, through the Power Cube Matrix,17 terms “spaces of engagement” to claim, initiate and demand participation towards effective political transitional processes.

There is need to advocate for victim-centred amnesty legislation and amnesty hearings that are victim-friendly, to enable victims to exercise their inalienable right to seek justice and redress. However, this can be best realised if democracy-supporting institutions and the state create agency for civic actors and promote citizen participation in public affairs. How can this succeed? NGOs should continue working with the government whilst maintaining some modicum of autonomy (although this is difficult, given the challenging state-civil society interactions in Zimbabwe). Peace-related organisations should join forces with other pro-democracy movements and push for a national reconciliation process that considers the efficacy and feasibility of amnesty in Zimbabwe. In addition, the victim-centred legislation should be protected from abuse by political entrepreneurs, who may want to exploit it for political expediency.

Conclusion

This article concludes that the missing link in the Zimbabwe national peace and reconciliation debate is a lack of inclusion of amnesty in the transitional justice discourse. While amnesty can facilitate the evasion of justice and perpetuate gross human rights violations and crimes against humanity, it can be deliberately effected to induce smooth political transition. Political hardliners guilty of crimes against humanity may decide to step down from power once their future safety is guaranteed. Nonetheless, there is need to balance justice and amnesty to avoid depriving victims of violence from accessing justice. Together with other transitional justice processes, a truth-for-amnesty formula can be a reasonable approach in the national healing discourse.

Endnotes

- Sims, Bryan (2008) ‘The Question of Amnesty in Post Conflict Zimbabwe’, Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/2445282/The_question_of_amnesty_in_post_conflict_Zimbabwe> Accessed 15 January 2016.

- Grange, Jason (2014) ‘The Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Did it Fail to Resolve Conflict between South Africans?’, Available at: <http://www.ejournalncrp.org/the-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-did-it-fail-to-resolve-conflict-between-south-africans/> Accessed 26 May 2016.

- Dugard, John (1999) Dealing with Crimes of a Past Regime. Is Amnesty Still an Option? Leiden Journal of International Law, 12(04), pp. 1001–1015.

- Mallinder, Louise (2007) Exploring the Practice of States in Introducing Amnesties. Study submitted for the International Conference ‘Building a Future on Peace and Justice’, Nuremberg, 25–27 June.

- United Nations (2009) ‘Rule-of-law Tools for Post-conflict States: Amnesties’, Available at: <http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Amnesties_en.pdf> Accessed 27 March 2016.

- The Government of Zimbabwe (1980) Amnesty (General Pardon) Act [Chapter 9.03]. Harare: Print Flow.

- Magaisa, Alex (2016) ‘The Big Saturday Read: Presidential Amnesty – A Short History of Impunity and Political Violence in Zimbabwe’, Available at: <http://alexmagaisa.com/big-saturday-read-presidential-amnesty-%E2%88%92-short-history-impunity-political-violence-zimbabwe/> Accessed 27 January 2016.

- Human Rights NGO Forum (2003) Enforcing the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe: A Report by the Research Unit of the Zimbabwe Human Rights NGO Forum. Special Report 3.

- Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) is a political party in Zimbabwe. It was established in 1961 as a militant organisation that fought for Zimbabwe’s independence, alongside the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU).

- The Lancaster House Agreement was reached from a constitutional conference, held in December 1979, to set the parameters for Zimbabwe’s independence from the British Authority. The agreement established a transitional framework for the Independence Constitution, ceasefire and pre-independence arrangements.

- Human Rights Watch (2002) Zimbabwe: Fast Track Land Reform in Zimbabwe. Human Rights Watch, 14(1A).

- Feltoe, Geoff (2004) The Onslaught Against Democracy and Rule of Law in Zimbabwe in 2000. In Harold-Barry, David (ed.) Zimbabwe: The Past is the Future: Rethinking Land, State and Nation in the Context of Crisis. Harare: Weaver Press.

- Sims, Bryan (2008) op. cit.

- Ibid.

- Booysen, Susan (2012) ‘Change and “New” Politics in Zimbabwe. Interim Report of a Nationwide Survey of Public Opinion in Zimbabwe: June-July 2012’, Available at: <https://www.freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/Change%20and%20New%20Politics%20in%20Zimbabwe.pdf> Accessed 13 March 2016.

- Habib, Adam (2013) ‘VC’s Post: A View from Habib: Leading a University at the Very Source of Civilization’, Available at: <http://blogs.wits.ac.za/vc/2013/08/24/leading-a-university-at-the-very-source-of-civilization/> Accessed 27 May 2016.

- Gaventa, John (2006) Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis. Institute of Development Studies Bulletin, 37(6), pp. 23–33.