Introduction

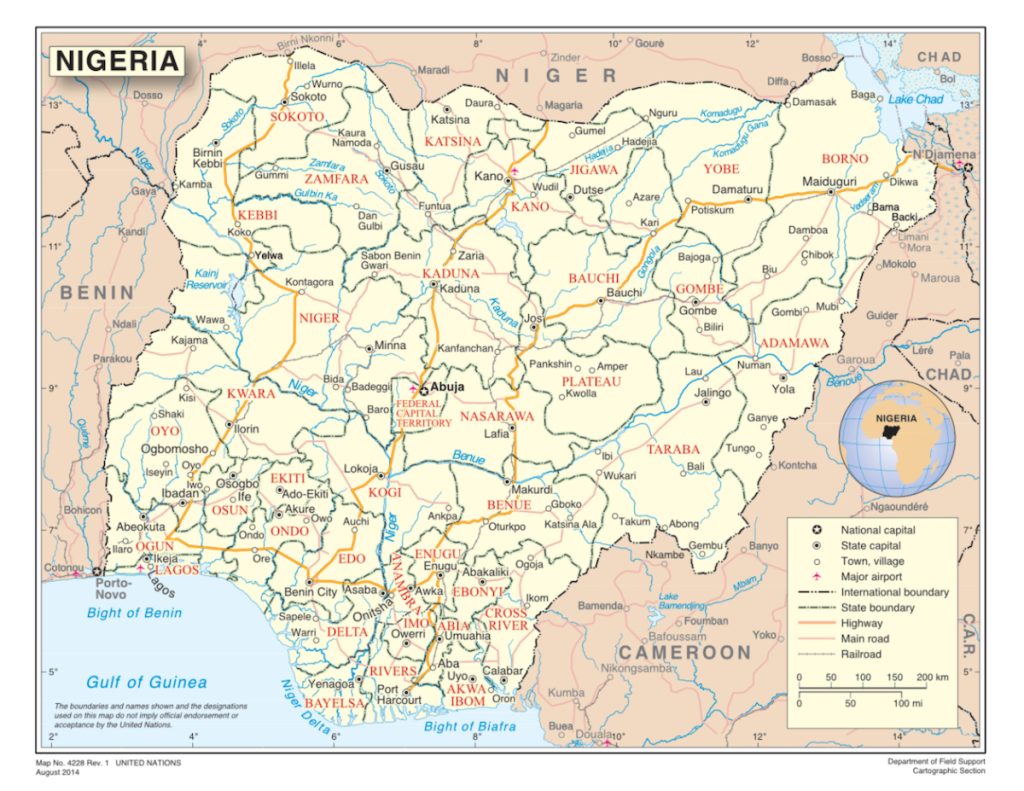

For over a decade, the Nigerian State has been confronting the ravaging insurgency perpetrated by Boko Haram and its splinter group, the Islamic State of West African Province (ISWAP), which has been responsible for about 350 000 deaths, and the displacement of over 2.3 million people.1Sanni, Kunle (2021) ‘Boko Haram: 350 000 dead in Nigeria-UN’, Premium Times Nigeria,Available at: <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/470476-insurgency-has-killed-almost-350000-in-north-east-undp.html> (Accessed 26 July 2022). It is estimated that over 15 million people have been affected by the insurgency and counterinsurgency (COIN) operations in North-East Nigeria.2Felbab-Brown, Vanda (2018) ‘In Nigeria, we don’t want them back’, Brookings, New York, Available at: <https://www-brookings-edu.cdn.ampproject.org/v/s/www.brookings.edu/research/in-nigeria-we-dont-want-them-back> (Accessed 26 July 2022). The activities of these groups, coupled with the recent armed banditry, have triggered one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.3Carsten, Paul and Onuah, Felix (2021) ‘Northeeast Nigeria Insurgency has killed almost 350 000 – UN’, Reuters, Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/northeast-nigeria-insurgency-has-killed-almost-350000-un-2021-06-24> (Accessed 25 July 2022). Unfortunately, the police mandated to handle internal security have, since the commencement of the insurgency, been overstretched and overwhelmed due to poor training and inadequate funding. Because of the combined effects of the Boko Haram insurgency, banditry, kidnappings, separatist agitations, ethno-religious conflicts, and the farmer-herder crisis, the Nigerian military has been drafted to play a frontline role in quelling the multifarious security crises in the country. This situation, among others, has largely marked the overwhelming engagement of the Nigerian army in internal security operations. However, some analysts and scholars have posited the danger of an expansive role of the military in the ongoing fight against counterinsurgency, claiming that it may threaten civil-military relations.4Ojo, O. Emmanuel (2008) ‘New Missions and Roles of the Military Forces: The Blurring of Military and Police Roles in Nigeria’, Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 11 (1&2), 1–18; Punch Nigeria (2022) ‘Military deployment in 36 States dangerous’, Available at: <https://punchng.com/military-deployment-in-36-states-dangerous> (Accessed 25 July 2022). Recently, Nigeria’s Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), General Lucky Irabor, stated that 80% of the country’s armed forces are presently engaged in internal security operations in all 36 states of the federation. This suggests, as several analysts have highlighted, that the Nigerian military has essentially taken over internal security, which is largely within the purview of police service.5Punch Nigeria (2022) ‘Military deployment in 36 States dangerous’, Available at: <https://punchng.com/military-deployment-in-36-states-dangerous> (Accessed 25 July 2022).

Interestingly, the increased role of the military in internal security operations has led to a rise in budgetary allocations from $1.5 billion in 2009 when Boko Haram onslaughts commenced to $2.57 billion in 2020.6Macrotrends (2022) ‘Nigeria Military Spending/Defence Budget 1960–2022’, Available at: <https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/NGA/nigeria/military-spending-defense-budget> (Accessed 27 July 2022). Sadly, studies indicate that systemic corruption in the military has undermined its effectiveness and legitimacy.7Onuoha, C. Freedom; Chikodiri Nwangwu and Michael I. Ugwueze (2020) ‘Counterinsurgency operations of the Nigerian Military and Boko Haram Insurgency: Expounding the Viscid Manacle’, Security Journal, 33, 401-426; Oriola, Temitope (2021) ‘Nigerian Soldiers on the War Against Boko Haram’, African Affairs,120(479), 147–175. According to Onuoha et al., institutional corruption in the Nigerian military is undermining COIN operations in the North East and has led to recurrent complaints of soldiers about their pitiable conditions of service and welfare.8Ikem, Patrick Afamefune; Onuoha, Freedom C.; Edeh, Herbert C.; Ononogbu, Olihe A. and Enyiazu, Chukwuemeka (2022) ‘Decoding the Message: Understanding Soldiers’ Mutiny in Nigeria’s Counterinsurgency Fight’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 33(8), 1372–1397. Reports on military operations in Nigeria suggest that these untoward developments largely account for the rise in the number of deaths recorded among the soldiers engaged in COIN operations.9Anderson, Eva and Page, Matthew (2017) Weaponising Transparency: Defence Procurement Reform as a Counterterrorism Strategy in Nigeria. New York: Transparency International. Furthermore, the Nigerian military either underestimated soldiers’ casualty rates or refuses to acknowledge deaths of non-commissioned soldiers killed in COIN operations.10Oriola, Temitope (2023) ‘Nigerian Troops in the War Against Boko Haram: The Civilian-Military Leadership Interest Convergence Thesis’, Armed Forces & Society,46(2), 275–309. Worse still, the military has taken it as an official position to cover-up or deny these accusations.11Abubakar, A. Tasiu (2017) ‘Strategic Communications, Boko Haram, and Counter-Insurgency’, Defence Strategic Communications, 3(Autumn), 139–170. As a result, several mutinies have occurred due to outdated weapons and equipment, high-handedness and apathy of senior military officers to their plight, long duty tours, and pervasive corruption in the military undermining their effectiveness in engaging the insurgents. Also, some soldiers have allegedly threatened to mutiny. For instance, in 2022, a soldier with the 23rd Brigade of the Nigerian army based in Adamawa state hinted of a possible mutiny due to the failure of authorities to address their welfare issues.12Sahara Reporters (2022) ‘Nigerian Soldier Warns Of Impending Mutiny, Laments Troops Pay N42,000 Each For Uniforms, Boots, Live In “Barracks Fit For Rearing Goats”’, Available at: <https://saharareporters.com/2022/06/09/nigerian-soldier-warns-impending-mutiny-laments-troops-pay-n42000-each-uniforms-boots> (Accessed 23 October 2023). While the military had previously court-martialled mutineer soldiers, and initial death sentences were passed on them, this was later changed to prison terms of ten years.

Mutiny is conventionally viewed as a criminal offence not only against the military, but also against the state.13Rose, Elihu (1982) ‘The Anatomy of Mutiny’, Armed Forces and Society,8(4), 561–574. This position has informed states’ proscription of the act and stipulated the death sentence for its perpetrators. However, studies indicate that democratic countries have substantially rescinded their implementation of the death sentence for mutineers due to rising human rights concerns.14Hamby, E. Joel (2002) ‘The Mutiny Wagon Wheel: A leadership Model for Mutiny in Combat’, Armed Forces & Society, 28(4), 575–600. More recently, studies have challenged the conventional view of mutiny as a criminal act carried out by unruly, disloyal and villainous soldiers.15Dwyer, Maggie (2017) Soldiers in Revolt: Army Mutinies in Africa. United Kingdom: Hurst & Company. For Dwyer, mutiny is not necessarily an act of insubordination, rather it is an action intended to open up dialogue with military or political leadership regarding soldiers’ expectations from them. This paper aligns with this perspective and anchors its analysis on it. The paper contends that instead of interpreting Nigerian soldiers’ mutinies as actions carried out by unruly, criminal or disloyal troops, their actions should be understood in the context of institutional failures which make the fight against insurgency so difficult for the soldiers that they have to take the risk and make their grievances known. In other words, seeing mutiny as dialogic may even stem its occurrence because it may harness soldiers’ perspectives on their welfare, living conditions, engagement with the enemy etc., which may help to develop better strategic and tactical options and objectives to overcome some of the shortfalls encountered in the COIN operations in Nigeria.

Dialogic view of mutiny in Africa: A theoretical discourse

Despite the vast literature on African militaries, adequate attention has not been focused on lesser acts of insubordination, such as mutiny,16Ibid, p. 15. and the viewpoints of the rank-and-file on COIN operations.17Oriola (2021) op. cit. Interestingly, these viewpoints are critical to gaining insight into the nuanced nature of mutiny in Africa. According to Boisvert, mutiny is a bottom-up expression of grievances within the ranks, which results in few premeditated or purposeful acts of indiscipline.18Boisvet, Marc-Andre (2019) The Malian Armed Forces and its discontents: civil-military relations, cohesion and the resilience of a postcolonial military institution in the aftermath of the 2012 crisis, PhD thesis, University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. p. 23. This definition suggests that the act of mutiny is perpetrated by lower ranking officers in the military, but does not provide details as to whether the mutinying soldiers may be expecting some corrective interventions from the government or not. Dwyer, on the other hand, defines mutiny as an act of collective insubordination in which military personnel revolt against lawfully constituted authority to express grievances and make explicit demands.19Dwyer (2017) op. cit. p. 16. While this kind of action may influence political leadership to respond to the demands of the mutinying soldiers, scholars generally agree that the implicit and explicit goal of mutiny is not to seize state power or instigate a change in those holding political offices.20Ibid.

However, it is important to note that the adverse effect of mutiny on civil-military relations and society is generally acknowledged. Moreover, mutiny is distinct from other military-related incidents, such as coups, protest by veteran or demobilised soldiers, and desertions.21Schiel, Rebecca, Jonathan Powell & Christopher Faulkner (2020) ‘Mutiny in Africa, 1950–2018’, Conflict Management and Peace Science,38(4), 481–499. Although coup attempts may almost appear to be an act of mutiny, scholars agree that the goal of the phenomena differ. While mutiny is a collective action by soldiers to protest or register their grievances with an expectation of corrective interventions from both the military, and in some cases, political leadership, on the other hand, a coup, from the outset, is aimed at overthrowing the political system.22Dwyer (2017) op. cit. Actions of out-of-service soldiers, such as veterans or demobilised soldiers, are not considered as mutiny because these categories of individuals are deemed to be outside of the armed forces. This is also the case for soldiers that desert or abandon their position or posts.23Schiel et al. (2020) op. cit.

In Dwyer’s analysis of mutinies in West and Central Africa, she argued that mutinies by soldiers are beyond material demands. Predominantly, soldiers’ mutinies have been described by state officials and analysts as pay revolt, and are, therefore, seen as primarily concerned with the material needs of the soldiers such as income, living conditions and food.24Dwyer (2017) op. cit. This is further supported by the fact that mutinies in Africa are mainly carried out by lower ranks commonly viewed as comprising less educated individuals and belonging to a lower socio-economic class. This view has been criticised for being too narrow by construing mutiny as pay revolt and assuming that meeting the material demands of soldiers automatically quells it. This view largely disregards other fundamental structural or normative issues, such as unfair treatment based on ethno-religious grounds and patron-client relations, replacing formal institutional reward systems and procedures, among others.25Ikem et al. (2022) op. cit. Such structural anomalies have been noted to account for mutinies in Africa. Therefore, an analysis of mutiny in Africa goes beyond the confines of the materialist perspective, which Dwyer remarked as being ‘unhelpful in assessing how or when soldiers decide to mutiny’,26Ibid, p. 5. to non-materialist issues of injustices borne out of structural anomalies embedded in most military institutions across Africa, especially Nigeria.

More recently, Dwyer has provided a more nuanced perspective on communication to the analysis of mutiny to better understand the undergirding rationale of the soldiers’ actions. This new perspective challenges the traditional views of the military institution and existing scholarship, which see soldiers’ mutiny as a repulsive crime against the state carrying the death sentence for perpetrators. In contrast, Dwyer argued that mutiny serves as a rational strategy of communication for soldiers to open up dialogue with authorities (military and political leadership) and elicit corrective interventions from them as regards their conditions of service and welfare generally.27See also Ikem et al. (2022) op. cit. The willingness of former Gambian President, Dawda Jawara, to dialogue with resentful returnee soldiers from their Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) peacekeeping mission in Liberia in 1991 and 1992, as well as the decision of Ivorian President Houphouet-Boigny to meet with mutinous soldiers about their demands for better welfare amid the government’s increase in taxes in the 1990s, both serve as examples of how sincere complaints of rank and file can be handled. Going by this dialogic logic rooted in the communication perspective of mutiny in Africa, Dwyer provides a more analytical and sophisticated means of unravelling the nuanced actions of Nigerian soldiers in the ongoing COIN operations. This dialogic approach closely aligns with Rose’s military managerial mode of leadership in which, like conventional corporate managers, leaders ‘are likely to seek mediation and compromise rather than confrontation in the face of collective discontent and may thus be increasingly unwilling to define opposition behaviour as mutiny’.28Rose (1982) op. cit. p. 573. Several self-made videos and interviews of implicated soldiers confirm that they carried out mutiny after authorities failed to respond to their complaints regarding outdated weapons and lack of equipment, poor welfare packages, and long tour of duty. In this regard, Dwyer further notes that ‘mutinies can more accurately be viewed as soldiers communicating deeper perceptions of tensions and injustices within a military environment’.29Dwyer (2017) op. cit. p. 574.

The ongoing COIN operations from the rank-and-file perspective

Despite numerous studies on the Boko Haram insurgency and the COIN operations being carried out by the Nigerian military, the perspectives of soldiers engaged at the tactical level have not been fully appreciated. Oriola avers that the perspectives of Nigerian soldiers provide ‘nuanced and textured micro-sociological insight [into] why Nigeria has been struggling to win the war against Boko Haram’.30Oriola (2021) op. cit. p. 173. Some soldiers expressed concern over the seemingly intractable nature of the war, particularly taking cognisance of their enviable peacekeeping efforts and experience abroad. A recent empirical study done by Oriola revealed that the soldiers are losing hope over the termination of the war since they believe that it has become a money-making machinery for certain highly-placed military officers, government officials, and their cronies. Several complaints by the soldiers about outdated and inadequate weapons and equipment have largely been ignored. For instance, the Soviet-era Shilka artillery guns and T-72 tanks were refurbished and deployed for the COIN operations.31Olatunji, Hakeem (2019) ‘Soldiers using Soviet-era Weapons to fight well-equipped Boko Haram’, The Cable, Available at: <https://www.thecable.ng/soldiers-using-soviet-era-weapons-to-fight-well-equipped-boko-haram> (Accessed 1 August 2023). This is one reason why Nigerian soldiers were frequently unable to put up a resistance against Boko Haram, resulting in military bases being overrun by the insurgents with many weapons and military equipment carted away. In the same vein, they claimed they were lacking the necessary military kits, and in fact, soldiers were reported to have been seen wearing slippers to the frontlines of the COIN fight instead of combat boots.32Ikem et al. (2022) op. cit. p. 1382. These developments further diminished the soldiers’ morale and informed the then Jonathan-led government to contract a South African private military company, Special Task, Training, Equipment and Protection (STTEP) International Ltd, to support the combined effort of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) comprising Chadian, Nigerien, Cameroonian and Nigerian troops to combat Boko Haram.

After the change of government in 2015, the merit of the soldiers’ complaints about weapons and equipment was realised upon the revelation of appalling corruption at the military high command. This informed why civil society organisations (CSOs) admonished the military against executing soldiers. In fact, there were calls for the cases of the soldiers to be revisited by the then newly appointed military leadership. Consequently, the then Chief of Army Staff (COAS), Lt. General Tukur Buratai, created a committee to reassess the soldiers’ case. As a result, in August 2015, the army recalled and absolved 3 032 officers who had been dismissed under the leadership of the previous COAS.33Asomba, Ikenna (2015) ‘More dismissed soldiers beg Buhari for Reinstatement’, Vanguard Nigeria, Available at: <https://www.vanguardngr.com/2015/09/more-dismissed-soldiers-beg-buhari-for-reinstatement> (Accessed 20 October 2020); also see Ikem et al. (2022) op. cit. p. 1388. Meanwhile, the counsel to the imprisoned mutineers, Femi Falana, argued that since the court martial had established that the soldiers’ offences were caused by the negligence of authorities to provide adequate weapons for them, as stipulated in Section 217 of the Nigerian Constitution, they should be pardoned. Moreover, the former CDS, Air Martial Alex Badeh, said during his pulling-out parade that he led a military that was not properly equipped and motivated to engage the insurgents.34George, Taiwo (2015) ‘Badeh: I headed a Military that lacked Equipment’, The Cable, Available at: <https://www.thecable.ng/badeh-headed-military-lacked-equipment> (Accessed 23 October 2023).

Notwithstanding the former CDS admission of the inadequacies which confronted his troops, this did not in any way exonerate him from the findings of the Presidential Committee on the Audit of Defence Equipment Procurement (CADEP) 2007–2015, instituted by President Buhari, which indicted serving and retired generals, including the former National Security Adviser (NSA), Col. Sambo Dasuki, service chiefs and civilians in a defence arms scandal involving US$15 billion in stolen military funding.35Alli, Yusuf (2016) ‘EFCC Uncovers $12.9b more Fraud in Arms Deals Probe’, Sahara Reporters, Available at: <https://saharareporters.com/2016/04/27/efcc-uncovers-129b-more-fraud-arms-deals-probe> (Accessed 23 October 2023). For instance, the former NSA was said to have awarded a contract worth US$500 million to a crony and financier of his principal (the former President Goodluck Jonathan) to renovate helicopters in 2014. The helicopters were later found to be unfit for combat deployment in COIN operations.36Solomon, Salem (2017) ‘Report: Corruption in Nigerian Military benefits Boko Haram’, VOA News, Available at: <https://www.voanews.com/corruption-nigeria-military-boko-haram-report> (Accessed 14 June 2022). Also, the CADEP discovered that over $125 million in defence contracts were awarded to a company on the same day it was registered.37The Nation (2018) ‘$2.1b deals: Ex-Army chief Minimah refunds N1.7b’, <https://thenationonlineng.net/2-1b-deals-ex-army-chief-minimah-refunds-n1-7b> (Accessed 20 October 2020). It was reported that past air chiefs, including then CDS, Alex Badeh, diverted N558.2 million monthly from the salary account of Nigerian Air Force personnel.38Jonathan, Zovoe (2016) ‘We traced 17 Accounts to Badeh-EFCC’, Punch Nigeria, <https://punchng.com/we-traced-17-accounts-to-badeh-efcc> (Accessed 1 August 2023). On the whole, the CADEP found that the NSA awarded 513 defence contracts worth US$ 8.36 billion; N2.19 trillion and €54 000, respectively, out of which 53 contracts were said to be failed contracts which amounted to US$2.38 and N 13.73, trillion respectively.39Ikem et al. (2022) op. cit. p. 1381. Following questioning by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), former Chief of Army Staff (COAS), General Kenneth Minimah, and the Chief of Air Staff (CAS) were forced to refund some of the stolen money while their properties acquired through corruption were seized by the CADEP.40Akinkuotu, Eniola (2016) ‘Arms Scam: Ex-NAF Boss, Amosu, returns N2.3bn to FG’, Punch Nigeria, <https://punchng.com/arms-scam-ex-naf-boss-amosu-returns-n2-3bn-to-fg>

Soldiers’ revolts

The continued indifference to the plight and complaints of COIN soldiers led to a revolt in May 2014. This was the first reported case of mutiny in the ongoing COIN operations in North-East Nigeria. The soldiers shot indiscriminately into the air, and reportedly shot at the car of the then General Officer Commanding (GOC) the 7th Division of the Nigerian Army, Major General Abubakar Mohammed. Although nobody was hurt, the military claimed that it was an attempted murder and the 12 soldiers involved were subsequently court-martialled. Following this, in July 2014, soldiers mutinied following the death of 23 of their colleagues and 182 soldiers wounded in a Boko Haram attack on a military base in Borno State.41British Broadcasting Corporation (2015) ‘Boko Haram Crisis: Is the Nigerian Army Failing?’ Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-31046809> (Accessed 4 April 2021). Again, on 4 August 2014, 54 soldiers of the 111th Special Forces Battalion refused the order of their commander to take part in a planned operation to clear Delwa in Borno State of Boko Haram terrorists who had besieged the community. It is not surprising to see the frequency of soldiers’ revolts in 2014.42Ikem et al. (2022) op. cit. According to Omeni, it was one of the most lethal years of the insurgency with the highest death rate of soldiers.43Omeni, Akali (2018) Counter-Insurgency in Nigeria: The Military and Operations against Boko Haram, 2011-2017. London: Routledge. In 2021, an SB Morgen (SBM) Intelligence report revealed that 985 security personnel were killed with the military suffering the highest number at 642 deaths.44Olaiya, T. Tope (2021) ‘Nigeria at war, SBM report reveals’, The Guardian, Available at: <https://guardian.ng/news/nigeria-at-war-sbm-report-reveals> (Accessed 26 July 2022). The report also indicated that 322 police officers, 11 Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC), and two Department of State Services (DSS) personnel were among those killed within the period.

In 2016, soldiers of the 21st Brigade of the Nigerian Army, on a mission to clear Sambisa Forest in Borno State, mutinied against their commanding officer and reportedly shot into the air, with some prepared to abandon the operation. They accused their senior officers of mistreating them and telling them lies.45Ogundipe, Samuel (2016) ‘Gunshots, Confusion in Borno as Soldiers Fighting Boko Haram go on Rampage’, Premium Times Nigeria, Available at: <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/218127-breaking-gunshots-confusion-bornu-soldiers-fighting-boko-haram-go-rampage.html> (Accessed 20 October 2020). In a viral video released by a soldier of 145th Battalion of the Nigerian Army based in Damasak, Borno State, he accused their commander of starvation, lack of water, and non-payment of their allowances without explanation.46Sahara Reporters (2021) ‘“We’ve Not Been Given Food For Four Days”– Nigerian Soldier in Maiduguri Laments’, Available at: http://saharareporters.com/2021/04/07/weve-not-been-given-food-four-days%E2%80%93-nigerian-soldier-maiduguri-laments> (Accessed 12 March 2022). Similarly, soldiers complained of being overpowered and outgunned by insurgents because they were deployed to fight without adequate supplies. Also, another army unit reportedly almost lynched their GOC, Major General Victor Ezegwu, for abandoning them without food and water while they battled the insurgents.47Ogundipe, Samuel (2016) ‘Nigerian Army General who lied about troops’ mutiny escapes lynching by hungry soldiers’, Premium Times Nigeria, Available at: <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/218308-nigerian-army-general-lied-troops-mutiny-escapes-lynching-hungry-soldiers.html> (Accessed 23 July 2022). In March 2021, the headquarters of the theatre Command of the COIN operations in Borno State were under siege when angry soldiers started shooting into the air in protest over the non-payment of their allowances and obsolete equipment.48Tunoh, Blessing (2021) ‘Soldiers Protest Poor Equipment, Unpaid Allowances in Borno’, Available at: <https://www.channelstv.com/2021/03/26/soldiers-protest-poor-equipment-unpaid-allowances-in-borno > (Accessed 27 July 2022). It is noteworthy, however, that the military has always denied the claims by the mutinying soldiers. An interesting dialogic example in 2017, instead of imposing punitive penalties, a top military officer acknowledged the predicament of the mutinying soldiers’ and pledged to resolve their concerns.49Lere, Mohammed (2017). ‘VIDEO: Why we went on rampage in Sambisa- Nigerian soldiers’, <https://www.premiumtimesng.com/video/219558-video-went-rampage-sambisa-nigerian-soldiers.html> (Accessed 26 July 2022). More recently, the current Chief of Army Staff, General Taoreed Lagbaja, may be following the accommodationist path, which inherently may entail interfacing with the rank-and-file soldiers to improve their welfare. This comes as General Lagbaja outlines his inclusiveness and adaptability-based leadership philosophies.50Orji, Ndubuisi (2023). CDS, COAS Promise to Prioritise Troops Welfare, Transform Military. <https://sunnewsonline.com/cds-coas-promise-to-prioritise-troops-welfare-transform-military/> (Accessed 20 October 2023). With reference to equipment, he recently said “We no longer rely on 1970 or 1980 equipment to fight the battle of 2023.”51Premium Times Nigeria (2023). Army Chief Lagbaja Lists Priorities, Says Soldiers have Modern Equipment. <http://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/608242-army-chief-lagbaja-lists-priorities-says-soldiers-have-modern-equipment.html>

Conclusion

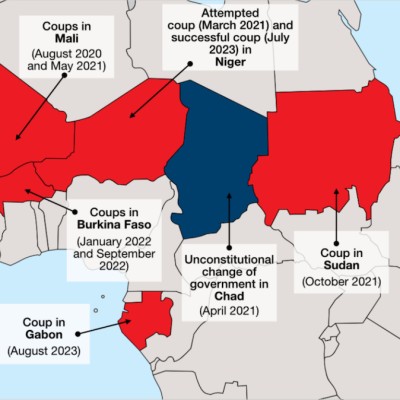

This article has argued that a more nuanced view is needed of various mutinies carried out by Nigerian soldiers in the ongoing COIN operations as a means to communicate their grievances amid military prohibition of such acts. This argument is germane as the military has been inundated with systemic corruption. The rising budgetary allocations have not been justified. This portends danger for Nigeria amid the multifaceted and immanent security threats in the country. With the rising cases of military coups in West Africa, it is instructive for the Nigerian military to be more responsive and rid itself of corruption. This will bolster its COIN operations against Boko Haram.

Patrick Afamefune Ikem is based at the Department of Political Science at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria.