Introduction

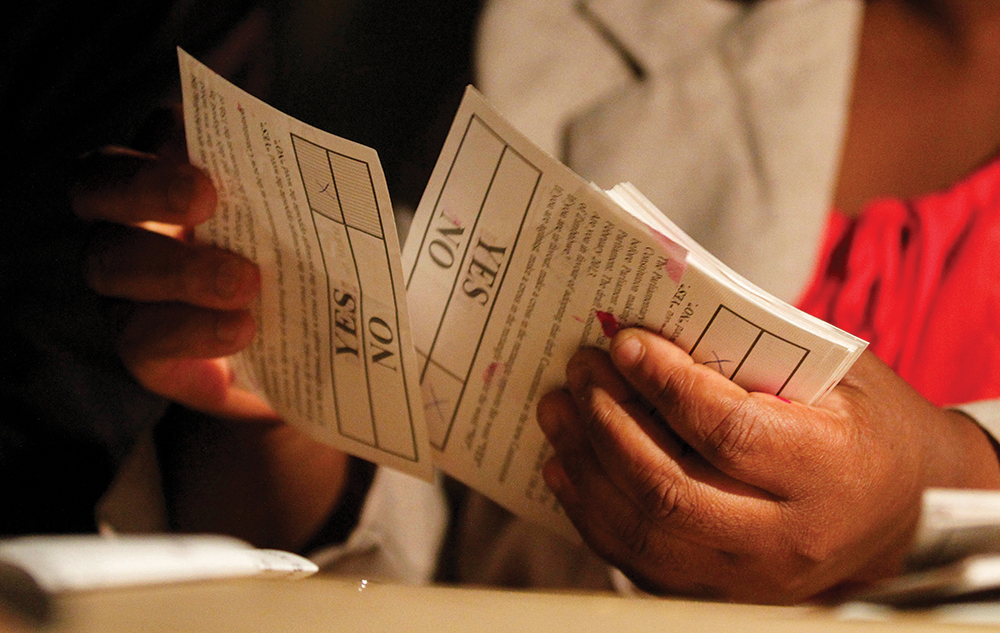

In 2013, Zimbabweans overwhelmingly endorsed the adoption of a new constitution through a referendum held in March 2013. The constitution was hailed by many as constituting a break from the past; thus the document represented an “aspirational nation”. The ”YES Vote” campaign drew support from across the political divide. An overwhelming 94.4 % of the electorate voted in support of the new constitution while the “No Vote” campaign fronted by the National Constitutional Assembly (NCA) garnered less than 5% of the national vote.1 One possible explanation for the overwhelming endorsement is that the proposed constitution touched on bi-partisan issues that the electorate saw as important in moving the country forward and breaking with the past. For example, it guaranteed freedom of speech and association, introduced presidential term limits and also proposed mechanisms to increase and enhance the visibility of women in national politics.

A closer analysis of the exercise, however, reveals that constitution making was in fact cumbersome. Political party representatives involved in the processes tried hard to outsmart each other in an attempt to sway the process to either camp’s advantage. So arduous was the process that the constitution making exercise had to be briefly aborted as the main political actors, namely, Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) and the two Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) formations reached a political stalemate. Once the challenging issues had been resolved, the process continued and a new constitution was finally birthed and adopted in May 2013.

Prior to all this, in the year 2000, a ZANU PF driven referendum had been overwhelmingly rejected by the electorate as it sought to entrench ZANU PF misrule and curtail people’s freedoms. However, there were some positives which the referendum in 2000 included but which also did not survive. Among other things, for example, it sought to deal with the issue of “women’s rights”. With the referendum rejected, women’s rights issues were also shelved and only resurfaced again in 2009 as the Constitution Parliamentary Select Committee (COPAC) spearheaded the constitution making process. And women’s rights was one of the fundamental issues agreed to under the Global Political Agreement (GPA) negotiations signed between ZANU PF and the two MDC formations.

This article offers insight into Zimbabwe’s political processes with particular attention to processes involved in the quota system. Quotas are methods used in politics as a means of addressing women’s macro and micro level needs in society. They have been implemented with varying degrees of success in South Africa, Liberia, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Burundi and Rwanda among other countries. It touches on issues of how the quota has been used in various circumstances to disempower and undermine women’s involvement in politics. Through highlighting the various structural and systematic challenges that Zimbabwean women face with regards to participation in politics, the article interrogates whether this model of gender empowerment has actually improved the conditions of women in the country. Finally, it sheds light on what might need to happen post 2023 to sustain “gains” reaped from the quota system should calls for the extension of the quota system go unfulfilled.

Zimbabwe’s Elections: Where are the Women?

Table 1: Women’s Representation in Zimbabwe’s Parliament 1980 – 2018

| Election Year | National Assembly | Senate | ||

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| 1980 | 9 | 91 | 3 | 37 |

| 1985 | 9 | 91 | 3 | 37 |

| 1990 | 17 | 133 | UNICAMERAL | UNICAMERAL |

| 1995 | 22 | 128 | UNICAMERAL | UNICAMERAL |

| 2000 | 14 | 136 | UNICAMERAL | UNICAMERAL |

| 2005 | 25 | 125 | 21 | 45 |

| 2008 | 32 | 178 | 23 | 70 |

| 2013 | 86 | 185 | 38 | 42 |

| 2018 | 85 | 185 | No Data Yet | No Data Yet |

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union2

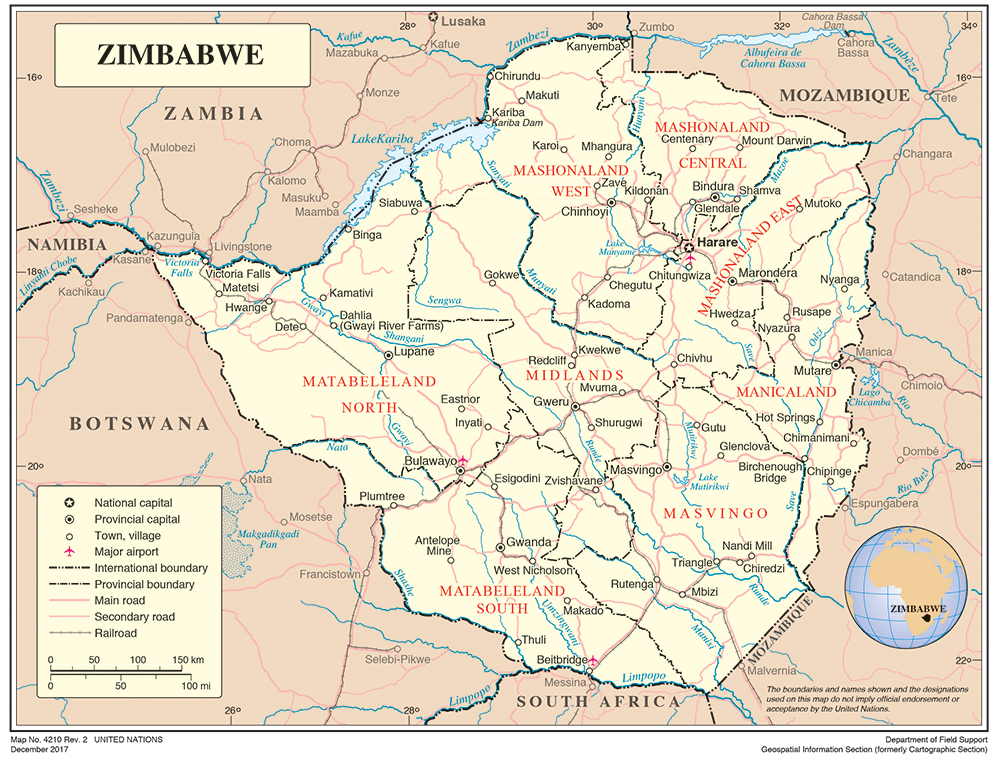

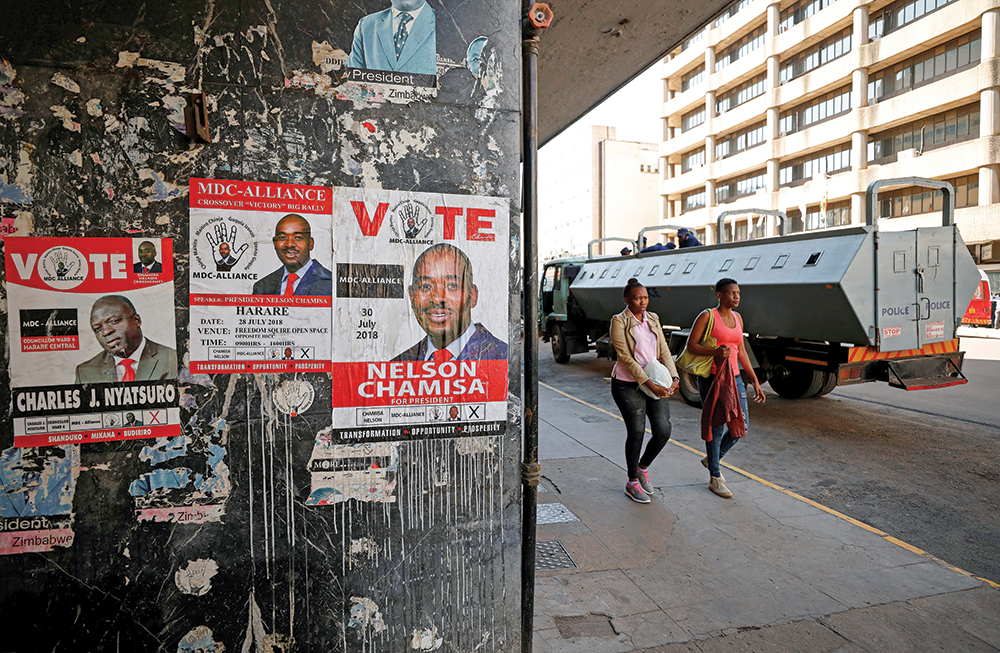

On 30 July 2018, Zimbabweans across the political divide headed to the polls to elect a government of their choice. Unlike previous elections in the country, the 30th July election was significant in two major ways. First, it was the first election in the country’s history where former president Robert Mugabe did not participate after he grudgingly tendered his resignation in November 2017 following a military assisted intervention. Second, it was the first election to have a significant number of women run for public office either as independent candidates or political party representatives. Some notable female contenders among many others included Thokozani Khupe, the leader of a splinter MDC faction; Joice Mujuru, leader of the National People’s Party (NPP); Fadzayi Mahere, who stood as an independent candidate for the Mount Pleasant constituency as well as Kudzai Mubaiwa and Duduzile Nyirongo who both ran as independent candidates for Councilor in Harare’s wards six and seven respectively.

At a surface level, one could make assumptions about Zimbabwean politics “‘coming of age”. However, a closer nuanced analysis reveals a worrying trend. The coming into effect in 2013 of the women’s quota system in Zimbabwe was applauded as a progressive step towards opening up the political space to women, while also addressing women’s macro and micro societal needs (see Table 1). In Zimbabwe Parliament is divided into two chambers, the Senate and the House of Assembly. The quota reserves 60 seats for women in the National Assembly while senators are elected based on a party list in which women and men are listed on an alternating basis with women always topping the list. The decision to implement quotas in many African countries came as a result of, albeit grudgingly, enacting international instruments such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) signed in 1979 at the Beijing World Conference (1995) and United Nations Security Resolution 1325 (2000) combined with other progressive regional and national legislation on equal opportunities between sexes.

In Zimbabwe, women’s lobby groups and gender activists who pushed for the inclusion of a quota system in the constitution making process envisioned a situation where Zimbabwe would join the ranks of Rwanda, Uganda, South Africa and Liberia, among others, that had, and continue to use, the women’s quota in varying degrees to achieve, or surpass, gender parity in parliament. A case in point is Rwanda. Zimbabwe’s gains have not been as clear cut. For example, a closer look and analysis of statistics with respect to women elected to parliament in Zimbabwe via the quota system reveals a shocking observation that may have escaped many. While in the Seventh parliament, women’s representation was 16 % and 25 % in both the National Assembly and Senate respectively, in the Eighth parliament, women’s representation increased to 35 % in the National Assembly and 48 % in the Senate.3 However, an obsession with numbers and statistics usually serves to obscure important considerations. For example, the number of women directly elected to parliament decreased as a result of the quota system. A quick look at the previous elections in 2008 is instructive. In 2008, there were 34 women directly elected to parliament compared to 26 women directly elected in 2013.4 In the just ended election, the number of women elected directly into parliament dropped to 25. The decrease in the number of women directly elected into parliament points to significant structural challenges with respect to the quota system. For example, there are reports that both ZANU-PF and MDC-Alliance (a coalition of pro-democracy parties) used the quota to prevent or block women from directly contesting public office because their seats were guaranteed.

Given this situation, the following questions are important for consideration: can quotas be relied on to deliver on and sustain women’s empowerment? Are quotas sufficient vehicles to change men’s and societies’ stereotypical beliefs about women? What also makes the Zimbabwean situation interesting is that according to constitutional provisions, the quota system will expire in 2023. There seems to be no interest on the part of government, at least for now, to extend the quota beyond 2023. Some notable political figures, such as Temba Mliswa – an independent Member of Parliament, have come out openly to condemn the quota system as ‘wasteful’ and “unsustainable”. With all the debates surrounding the quota system and the predominantly masculine nature of Zimbabwean politics, combined with a decline in the actual number of women directly elected to parliament in the last two elections, the quota may have worked to undermine women’s participation in politics.

Another challenge levelled at quotas is that they have a tendency to bring to parliament “unqualified” women who are more concerned with toeing the party line. Politics of patronage work to the disadvantage of experienced and qualified women who lack the necessary political capital to get into parliament. The argument here is that “token representation” brings to parliament women more concerned with toeing the party line than advancing the interests of other women and society at large. They essentially become political proxies for male politicians who ride on their blind loyalty to entrench male dominance and leadership. Women who fall out of favour with the ‘”system” are left in the political wilderness never mind their impressive track record in parliament. A notable example is Priscilla Misihairabwi-Mushonga, of the MDC formation led by Welshman Ncube, who was dropped from the party’s proportional representation list after she fell out of favour with the political system. In Zimbabwe, women parliamentarians elected through the quota system have had to carefully navigate the political terrain to avoid “outsmarting” directly elected parliamentarians or upsetting the political system. For example, in an interview with one of the country’s leading newspapers, proportional representation legislator for Bulawayo, Dorothy Ndlovu, lamented how she was viewed as a threat to sitting members of parliament (MPs) in the constituencies to which she was elected and therefore has to seek permission from them to pioneer and champion any developmental projects in their respective constituencies to avoid conflicts.5

However, the quota system must be applauded for averting a potentially catastrophic situation with respect to women’s involvement and participation in national politics in Zimbabwe. As demonstrated in Table 1, Zimbabwean politics has always sought to advance the interests of men while subverting those of women. For example, in the first nationalist government of Robert Mugabe, women were severely underrepresented, occupying only nine seats out of a 100 seats.6 While the number of female parliamentarians has increased since 1980, there are still concerns that change is not happening fast enough and women continue to face political, social and economic exclusion. There were concerns raised by women aspirants in the run up to the 2013 harmonised election that political parties, mainly ZANU-PF and the Movement for Democratic Change – Tsvangirai (MDC-T) formation – were employing subtle tactics to elbow out female contenders. The tactics included allocating women to constituencies in opposition strongholds while men contested relatively easy-to-win constituencies where each respective party enjoyed popular support. In the absence of the women quota, there is no doubt that the number of women elected into parliament in 2013 and 2018 would have taken a dip. Even the 34 % increase from 19 % in 2008, while remarkable in the history of the country, still falls far below the 50 % gender parity representation by 2015 envisioned in the SADC protocol on Gender and Development.7 Political victimisation, violence associated with elections and economic and financial constraints are some of the reasons women struggle to compete for political office with men on equal footing. For example, in the recently ended ZANU-PF primaries for the 2018 elections, female aspirants like Epworth legislator Zalera Makari had to flee a mob of ZANU-PF youths who besieged her campaign with the intention to oust her from the constituency to make way for a male contender.8

Way Forward?

Given the circumstances surrounding the quota system, the article advances a few recommendations as Zimbabwe’s 9th parliament comes to life, signalling the second and last phase of the quota. What is clear so far from the Zimbabwean experience is that quotas alone are not sufficient to transform the attitudes of men about women in general, and their political aspirations in particular. What is also clear is that while having numbers is critical for voting and passing laws, the quality of representation is of paramount importance. If political parties are sincere about advancing the needs of women in particular, and society in general, one would expect that parties move beyond political networks based on patronage, clientelism and nepotism to nominate experienced and qualified women from outside their political networks to advance the interests of women. This reasoning makes sense in a context where majority of the electorate are women. The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) recently released data on voting demographics for 2018 and it found that women constituted 54.64 % of registered voters.9 Also, in spite of the fact that the eighth parliament had the highest number of female parliamentarians in Zimbabwean history, the attitude displayed by political parties towards women aspirants is disappointing. Women like Thokozani Khupe, Jesse Majome and Joice Mujuru have in the recent past been subjected to violence and senseless victimisation by their political opponents. In February 2018, Thokozani Khupe was almost set ablaze by MDC-T youths going by the moniker of the “party vanguard” at the funeral of MDC-T stalwart Morgan Tsvangirai.10 She was accused of being a dissident and fanning “tribalism” in the wake of MDC-T leadership wrangles that followed the death of Morgan Tsvangirai in February 2018.

One could possibly argue too that the attitude of the media, both public and private, has unwittingly played a role in demonising and trivialising women. For instance, instead of capturing issues generated by women in parliament and in their respective Portfolio Committees, the media has instead focused on negative stories about the personal lives of the female MPs, their relationships to men and their education or lack of it.11 The media environment in Zimbabwe remains skewed in favour of the male voice while trivialising that of women and their concerns.

Women across political parties need to find common ground to advance their collective interests as a special interest group. Section 17 of the constitution of Zimbabwe mandates the state to ensure promotion of full gender balance in Zimbabwean society. This constitutional provision gives the state the right to enact laws needed to ensure than women constitute at least 50% of membership in all commissions, elective and appointed government bodies.12 This constitutional provision offers women a fresh opportunity to insist on full compliance with the constitution. Alternatively, women parliamentarians – with the support of civic society, gender lobbyists and activists – could demand that parliament amends the Electoral Act to make explicit the demands of women with respect to representation at all levels of government. Section 17 of the constitution is ambiguous and can be made clearer. Section 17(1)(b)(ii) of the constitution reads as follows;

The State must promote full gender balance in Zimbabwean society and in particular …must… take all measures including legislative measures needed to ensure women constitute at least half of the membership of all commissions and all elective and appointed governmental bodies established by or under this Constitution or any Act of Parliament.

This provision could be made clearer by clarifying the exact number of seats to be allocated to women at both parliamentary and local government level.

Finally, women must hold their political parties accountable by pushing for the adoption of a specified quota system in line with regional and international instruments. The challenge with political party quotas in Zimbabwe is that they are based on political accommodation. For example, the MDC has a voluntary 30% female quota which is always violated in favour of men. If recent events involving primary elections in both ZANU-PF and the MDC-Alliance are anything to go by, these developments must rally women across the political divide towards a common objective: for example to put pressure on their leaderships to insert and implement provisions in their respective party constitutions for the inclusion of women – based on constitutional mandates rather than the present voluntary quotas. All parties can learn from the experience of the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa. The ANC has managed to surpass its 30 % female quota in parliament by implementing mechanisms that ensure that women are “adequately” represented at all levels of party structures.13 By its own admission, as of 2009 the ANC had almost achieved gender parity in parliament with 49.2 % of National Assembly members being women.14 Political parties in Zimbabwe need to go beyond rhetoric and implement similar mechanisms within their structures.

Conclusion

It is a given reality that the number of women contesting political office in Zimbabwe is significantly lower than that of their male counterparts. It is also clear from the preceding discussion that increasing the number of women in parliament without transforming the political and social institutions that suppress women could prove unsustainable in the long term. While quotas are an important starting point, sustained transformation requires that we go beyond quantitative analysis to qualitative analysis. By examining the deep structural challenges that prevent women’s effective participation in politics, we take the conversation to a new level. Misdiagnosis can only result in ineffective and unsustainable interventions. The rampant victimisation and sexualisation of women points to a larger problem that quotas may not sufficiently address. The media, being the fourth estate, also has a crucial role to play in this regard through gender-sensitive reporting as well as demystifying old and unhelpful gender stereotypes. Equally important is for women across the political divide to bury their political hatchets and work towards a common good – advancing the interests of society. The new Zimbabwean constitution is aspirational. It presents activists and gender lobbyists with an opportunity: to pressure parliament and institute systems that will ensure realisation of the gender equality dream.

Endnotes

- African Democracy Encyclopaedia Project, ‘Zimbabwe: 2013 Referendum Results’, Available at: <https://www.eisa.org.za> [Accessed 05 July 2018].

- Inter-Parliamentary Union ‘Zimbabwe House of Assembly’, Available at: <http://archive.ipu.org> [Accessed 07 July 2018].

- Research Advocacy Unit (2017) ‘Increasing Women’s Political Participation’. Policy Brief No.2/17, Available at: <researchandadvocacyunit.org> [Accessed 30 June 2018].

- Ibid.

- Moyo, Nizbert (2018) ‘Challenges of being a P.R Legislator’, Available at: <https://www.newsday.co.zw> [Accessed 11 July 2018].

- Gudhlanga, Enna (2013) ‘Shutting Them Out: Opportunities and Challenges of Women’s Participation in Zimbabwean Politics – A Historical Perspective. Journal of Third World Studies, 30, (1), pp. 151-171.

- SADC (2008) ‘Protocol on Gender and Development’, Available at: <https://www.sadc.int> [Accessed 06 July 2018].

- Langa, Veneranda (2018) ‘Women Bear the Brunt of Political Violence’, Available at: <https://www.newsday.co.zw> [Accessed 09 July 2018].

- Zimbabwe Election Support Network (2018) ‘Comment on the ZEC BVR Provisional Statistics’, Available at: <http://elections.co.zw> [Accessed 10 July 2018].

- Chidza Richard (2018) ‘MDC-T Trio Survives Mob Attack’, Available at: <https://www.newsday.co.zw> [Accessed 08 September 2018].

- Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe [MMPZ] (2012) ‘Media Representation of Women in Politics’, October-November 2012.

- Veritas ‘The Constitution of Zimbabwe 2013’, Available at: <veritaszim.net> [Accessed 11 July 2018].

- ANC (2009) ‘Manifesto: Working Together we can do More’, Available at: <http://www.anc.org.za> [Accessed 08 July 2018].

- Ibid.