Introduction

Language and politics are intrinsically linked. Some argue that language is founded in an exclusionary way as a means of distinguishing allies from enemies, and of grooming allies and potential allies. Similarly, others locate the origin of a language in the need to form coalitions of a critical size, representing the initial form of social and political organisations. In the same vein, in his attempt at disclosing the enigma of language embedded in the political nature of human beings, Aristotle states:

…Yet it is an idea with a venerable heritage: hence it is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man by nature is a political animal… now, that man is more of a political animal than bees or any other gregarious animal is evident. Nature, as we often say, makes nothing in vain and man is the only animal who she has endowed with the gift of speech.1

This implies that the very act of language is political in its nature. It reveals language as a necessary part of politics in every corner.

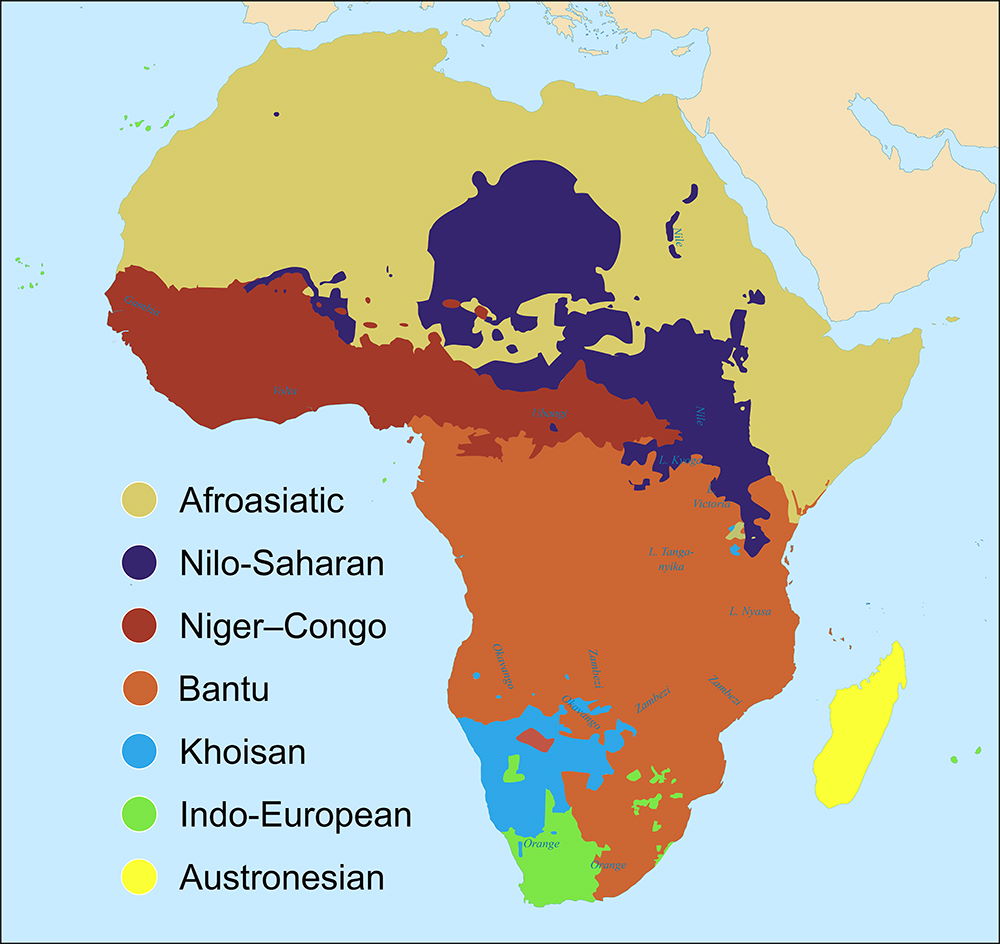

Sub-Saharan Africa is a very linguistically diversified region. This diversity is also coupled with cultural and ethnic variations. Building stable national identities in the vast majority of post-colonial sub-Saharan African states is often a problematic task, mainly because of the language factor. This compelled Ndhlovu to argue:

Any African studies discourse that overlooks the role and place of language would be incomplete because language occupies an important position in any meaningful dialogue on African development and on Africa’s engagement with herself and with the wider international community.ii

In the immediate aftermath of the colonial era, several sub-Saharan African countries saw the development of what can be referred to as “linguistic nationalism” as a way of contesting a state-directed effort of linguistic homogenisation. This attempt of homogenisation or the “one nation – one language” motto is evident in some cases, for example in Tanzania and Ethiopia. Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia attempted to promote one language as part of their nation-building projects. Such nation-building projects can be explained in two ways. One is the recognition of a single language at the expense of others – or what is termed an “assimilationist” language policy. The second explanation falls under the pragmatic need to promote one language that may serve all as the language of wider communication. Linguists from Ethiopia – for example, Leyew3 – accorded the second explanation as the rationale for their attempt at nation-building.

In post-colonial situations, the choice between the colonial language and an indigenous language was almost always politically driven, although in different ways in different places. The politics of language choice becomes particularly difficult when institutional selections have to be made, including questions such as: in what language/s will the government conduct its activities and communicate with its citizens, and what will the language/s of education be? It has been seen that non-democratic language policies are linked to bloody conflicts and ethnic tensions. In Ethiopia, for example, the language of “WoGaGoDa” was undemocratically introduced in the 1990s, aimed at uniting the ethnic Wolaita, Gamo, Gofa and Dawro groups. The people of the region rallied in opposition to the government – which claimed many lives and finally resulted in the withdrawal of this language policy and the creation of new, fragmented administrative structures.

The scramble for Africa introduced interesting dynamics in language, ethnicity and the nation-state nexus. It carved sub-Saharan Africa into new political entities without paying any regard to longstanding political, cultural and linguistic frontiers. This led to an emergence of African states having no solid foundation and where divergent ethnic groups became compatriots, as was the case in Nigeria. Another aspect of this is former unitary groups that were separated into two or more nations – as is evident in the Yorubas, who belong to Nigeria and Benin; the Ewe in Ghana, Togo and Benin;4 the Somalis in French, British and Italian Somaliland, and so on.

Language is an important factor of identity formation, and given the multilingual nature of Africa, political discourse related to ethnic and nation-state issues founded on the language factor is crucial to a holistic understanding of the situation. A brief glance at divergent conceptualisations of multilingualism in sub-Saharan Africa may enrich the discussion of language, ethnicity and the nation-state nexus.

Competing Views on Multilingualism

Two diametrically opposite views have emerged with respect to the presence of numerous languages across the various countries of sub-Saharan Africa. The first view capitalises on the negative consequences of multilingualism, associating it with many problems – such as ethnic conflicts, political tensions, and poverty and underdevelopment. This school of thought states that language diversity is “a bane of African unity, whether at the national, regional, or continental level”.5 Multilingualism is regarded as a burden, particularly when considered in the context of the extent of resources needed to promote the use of many languages in the areas of education, media, law and administration, business and commerce, and international communication. Moreover, the presence of many languages is equated with economic backwardness, while the existence of a single language is associated with economic prosperity and political stability. Linguistic heterogeneity is further associated with poor economic performance, insufficient provision of public goods, higher levels of corruption, less social trust and a high probability of internal conflict.

The second perspective on language diversity, which is based on a post-modern human rights discourse, demonstrates the indispensability of multilingualism. This can be seen within the context of democracy and human rights, where the right to language choice is considered an integral part of fundamental human rights. Rather than being a costly obstacle to development, nation-building, national unity, political integration and social cohesion, Buzási argues that multilingualism is “considered to be an asset”.6 The premise in the second school of thought rests on the point that every language in a multilingual society has the right to exist and to be given an “equal opportunity to develop legal and other technological limbs to flourish”.7 As a relatively new approach, some scholars suggest that people must be careful in interpreting linguistic diversity as a completely harmful societal condition that must be eliminated.

Some linguists indicate ambivalence on the issue of multilingualism, with the argument that the abundance of languages in Africa is attributed to be the cause of the continent’s predicaments, particularly in education and politics. At the same time, they also state that multilingualism appears to have helped Africans to gain a wider cultural understanding and enhanced them culturally to acquire forbearing and affable personalities. Beyond the either/or debate, what is more important is the need to accept the reality that the continent is linguistically diversified, and language in and of itself (or language per se) is not the problem – and that its management plays a significant role in eliminating challenges. Moreover, in a region such as sub-Saharan Africa, where a primordial conception of ethnicity dominates the political environment, the language factor needs special attention as being an essential marker of ethnic identity.

The Concomitance of Language and Ethnicity

The language-ethnic identity relationship discourse provides considerable insights into the link between language and culture. Each language is tied to distinct ethnic dynamics, and a strong emotional attachment to language and ethnicity is the norm in sub-Saharan Africa. The cultural context , as Fishman argues, is “shaped by its language”.8

Each ethnic group in the region expresses and identifies itself by the language it speaks. It is not uncommon to hear a “Ghanaian, Nigerian, Ugandan, Sierra Leonian, Cameroonian, or Togolese refer to somebody as ‘my brother’ simply because they share the same language and ethnic group background”.9 Sameness of language and ethnicity serves as a basis in defining bonds of acceptance and togetherness, identity, separateness, solidarity, and brotherhood and kinship. Language is a “reliable criterion for ethnic identity and social identity, in its most general sense, is reflected in linguistic behavior”.10

Before contact with the outside world, particularly with Europeans, Africans predominately lived in distinct ethnic and linguistic groups. One can argue that the various ethnic groups lived autonomously to each other before the advent of colonialism. Each ethnic group had its own quasi-political and administrative structures, its particular language and, often, its own cultural values. The various ethnic groups could be said to constitute “states”, with members speaking the same language.

In Ghana, for example, “[T]he Akan saw themselves as a state, and the Akan language performed a dual function.”11 The language both brought the Akan people together and set them apart from other ethnic groups. The same phenomenon also applied elsewhere in the region.

Each African language thus served as a means of self-expression and defined the intra-ethnic communication of identity groups. Each language effectively constituted a binding force that linked families, lineage, clans and the entire ethnic group. Languages in sub-Saharan Africa are said to constitute the storehouse of ethnicity, essentially because each ethnic group expressed and identified itself through the language it spoke. Moreover, in conditions where there were larger ethnic groups, minor differences in dialectsled to the creation of more organic and cohesive small units. Within ethnic groups, therefore, language persisted as an icon of the group’s distinctiveness, as well as the group’s cultural heritage.

In sub-Saharan Africa, language often appeared to be a “passport to ethnic origin, just as ethnic background was indexical of a language”.12 Since ethnicity and linguistic affinity overlap, they were also instrumental in strengthening the groups and in consolidating their defences against invasion by outsiders. Speakers of the same language who belonged to the same ethnic group experienced solidarity and strong bonds in any situation of strife and happiness. But this is not to argue that complete unity is automatically engendered through the agency of language. The Akan of Ghana found themselves in internal conflict more times than they fought with other ethnic groups. Similarly, in Somalia and Zanzibar – where a relative homogeneity prevails in terms of ethnicity – violence and unrest in the post-Mohamed Siad Barre era and early 1960s respectively illustrated that common language by itself is not a remedy for avoiding intragroup conflicts. Despite such anomalies, however, the colonial enterprise impacted significantly on intergroup and intragroup communication.

As a result of contact with European traders, explorers, missionaries, educators, colonial officers and even settlers in certain areas, new and larger communities – which formed a conglomeration of various ethnic and linguistic backgrounds – came into existence. New political frontiers entered the ethnic divide and led to situations where inhabitants were subjected to being torn between their ethnic and linguistic allegiances and allegiances to the state. These situations resulted in political unrest.

In the 1960s and 70s, sub-Saharan Africa saw the blossoming of the ethnic revival movement. Politically, this era was marked by struggles for independence. What the then politicians failed to give due consideration to was that the almost irrevocable bond between language and ethnicity had resulted in the development of enduring stereotypes of those who shared a language and related ethnic identity. In Nigeria, for example, some stereotypes were “the Ebiras as noisy, the Hausas as self-loving, domineering, careless, and hating European education; the Yorubas as gullible, unreliable, and betraying; the Idomas as promiscuous, and the Igbos as lovers of money and greedy”.13

The ethnic consciousness of the time brought about a reawakening of resentful feelings. Some members of ethnic groups regarded themselves as superior to all others and devalued languages other than their own – and the people who spoke such languages. The ethnic revival movement did little to discourage the resentment of members of other ethnic and language groups; it hardly promoted inter-ethnic understanding beyond the official level.

Some ethnic groups were associated with significant discriminatory, prejudicial and stereotypical images, and people discouraged members of their ethnic grouping from interacting with such stereotypes. In some instances, there were secessionist attempts – as was the case in Biafra, Nigeria, in the late 1960s, or the Antor secessionist scare in Ghana in the late 1950s. In other cases, strong ethnic feelings led to “ethnic cleansing”, as was observed in Rwanda and Burundi, and the civil war in Liberia.

Although people could, with difficulty, live together as one nation and acquire the feeling of oneness, at the same time each ethnic group forming the state had specific characteristics – such as language, an alleged common psychological make-up, religion and so on – that distinguished them from others. Although living in the same country, they continued to see themselves as distinct ethnic groups. Thus, although politicisation may help transform ethnic identity into nationalism elsewhere, in sub-Saharan Africa the reverse happened. Politicisation perhaps aggravated ethnic affiliations and jeopardised the multi-ethnic feature of Africa’s statehood.

More importantly, the ethnic revival – and accompanying strong ethnic identity feelings – brought with it political exclusionism and unique voting patterns during elections. In most sub-Saharan African countries, politicians could simply win the votes of members of their ethnolinguistic groups, in spite of their professional incompetence. The ethnolinguistic divide thus dominated the political landscape, to the detriment of meritocracy. A good example is the current situation in Ethiopia. Of the estimated over 100 opposition parties that now exist, very few of them transcend the ethnic divide. The ruling coalition itself, which has ruled the country for the past 28 years,14 is a formation of parties organised according to an ethnolinguistic arrangement. This political modus operandi makes ethnolinguistic identity and politics inseparable. In addition, Ethiopia institutionalised the intermingling of the two factors with a federal structure based on an ethnolinguistic formula – which, ipso facto, is likely to result in further divisions in the country.

Language and the Nation-state Discourse

The concept of the nation-state is vague. Delanty articulates it as such: “The state is the government and its institution; the nation is best described as some kind of grouping of people who identify with each other, be it for cultural, ethnic, linguistic, or historical reasons. The nation-state is the marriage of the two ideas.”15

The nation-state in the context of policy and planning operations has been problematic in sub-Saharan Africa for numerous reasons. First, the nation-state narrative in Africa is marked by the arbitrariness of boundaries from the partitioning of Africa at the Berlin Conference in the 1880s. Ethnic nationalities were bisected and trisected by colonial boundaries, and people with diverse – and, in some cases, conflicting – aspirations were lumped together in one nation. Thus, the nation-state narrative seems to have been formed to fail – or at least to face formidable difficulties in succeeding. Second, migration and displacement as part of the post-modern condition in Africa have diffused once-homogenous communities, particularly in urban areas where diverse communities exist. These two conditions – at times jointly, at other times separately – pose a challenge for the success of the nation-state framework.

The language factor is an essential condition in sub-Saharan Africa’s post-independence quest for a nation-state. In the region, central government-authored policies often do not reflect the reality of language-use needs and practices of the majority of the populous within that particular state, who either do not have the official language of their own vernacular or possess only modest competence in those languages that are deemed official. Faced with two ideological positions – the 19th century European nation-state ideology on the one hand, and the 20th/21st century African renaissance ideology on the other – language planners and decision-makers in Africa found themselvesin a complex dilemma. The academic and political discourse on the language factor in post-colonial Africa was highly ideologised. The ongoing debate suffers from a mismatch between the multilingual realities in African post-colonies and the political ideology that governs the mainstream discourse on nation-building inside and outside of Africa.

The mainstream discourse on nation-building is based on ideological positions that expound official monolingualism, which promotes one colonial language. With the reality that most African countries are essentially pluralistic in terms of language, culture and ethnic compositions, such official monolingualism opts for some kind of neutral or unifying language. The idea is that such a heterogeneous reality should conform to the Westphalian model of a nation-state, which is characterised by factual or ideologically postulated linguistic, cultural and ethnic homogeneity, ideally allowing the constituents of the polity to speak of one single “nation” populating its own nation-state.

The ideology that promotes the import of such policies – that is, the official monolingualism policy – is basically Social Darwinist16 by a prior acceptance of the essential evolutionary difference that exists between human societies, with some being more advanced than others, and thus legitimises colonialism. As far as language policy is concerned, it favours what linguists refer to “exoglossic monolingualism” – that is, the promotion of ex-colonial languages in the guise of neutrality and unity. This disregards the historically grown sociocultural realities in Africa with roots in the continent’s characteristic territorial multilingualism. Such an official monolingualism policy fosters language attitudes that target the eradication of multilingualism for all official purposes, including in formal education, in emergent post-colonial nation-states. Put otherwise, the ideological presupposition is that modern statehood in Africa must be “de-Africanised” to match Western prescriptions. This widely shared perspective has been – and remains – under sharp criticism for its inherent racism and continued linguistic and cultural imperialism.

In its 2015 edition, the Ethnologue17 identifies 2 138 languages in Africa, putting aside the theoretical challenge of language and dialect. On average, there are 40 languages per state. This further implies that most African ethnolinguistic groups do not have their own nation-state. Thus, one might infer that the Western notion of the nation-state, anchored on the idea of official monolingualism, makes little to no sense in the African context, fundamentally, because sub-Saharan Africa is multilingual, by and large.

The argument that views multilingualism as threatening or blocking national unity and social coherence – and therefore, by implication, policies that would officially accept multilingualism are detrimental to socio-economic modernisation and development – is a myth based on a monistic Western nation-state ideology. The Somali experience perfectly matched the nation-state formula but the country remained in political crisis. The Somali people, who share more or less the same language, culture, religion and perhaps even very similar ethnicity, remained in a serious political crisis for nearly three decades. The myth of multilingualism as threatening to social coherence is used as political propaganda in post-colonies for two reasons. First, it is used to discredit multilingual policies that would include indigenous languages. Second, it is used to maintain the hegemonic dominance of the language of the former colonial master – and, consequently, to avoid jeopardising the quasi-natural privilege of the “owners” of the language of power.

Conclusion

The issue of language in sub-Saharan Africa dominates the political arena in a significant way. The politics of ethnicity and the nation-state cannot be examined without the language factor, as the sense of ethnic self is created and perpetuated by language. Ethnic and linguistic identification are still at the centre of the sociopolitical and cultural lives of sub-Saharan Africans. Even in those countries that may constitutionally ban political mobilisation along ethnic divides, such as Kenya, the driving force behind political office is ethnolinguistic identity.

It is observed that in sociocultural life in sub-Saharan Africa, ethnolinguistic identities determine privileges, positions, achievable goals and aspirations. Ethnic identity is preserved through language, and ethnicity has been one of the many tools and strategies for the assertion of superiority and the denial of, or protest against, being labelled ethnolinguistically different or competent.

With the discourse of the nation-state that has dominated the sub-Saharan Africa political environment in the post-independence period, in effect it can be observed that although several different ethnic groups are lumped together in one polity, there is an absence of a strong sense of political belonging. The situation of offering little or no emphasis to various African languages with the intent to unify people by promoting a colonial language/s under the guise of neutrality experienced serious challenges, which remain. The sustained use of colonial language created a form of dejection in the masses, and excluded a large populous from participating in public activities and from making decisions affecting their own lives. This reality reinforces people’s need to intensify their links with their ethnic groups, which are linguistically and culturally accommodating.

Endnotes

- Aristotle (1885) The Politics of Aristotle (translated by Jowett, Benjamin). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ndhlovu, Finex (2008)Language and African Development: Theoretical Reflections on the Place of Languages in African Studies. Nordic Journal of African Studies,17 (2), pp. 137–151.

- Leyew, Zelealem (2012) The Ethiopian Language Policy: A Historical and Typological Overview. Ethiopian Journal of Languages and Literature, XII (2), p. 9.

- Badejo, Rotimi (1989) Multilingualism in Sub-Saharan Africa.Africa Media Review, 3 (2), p. 42.

- Zeleza, Paul Tiyambe (2006) The Inventions of African Identities and Languages: The Discursive and Developmental Implications. Selected Proceedings of the 36th Conference on African Linguistics. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 14–26.

- Buzási, Katalin (2016) Languages and National Identity in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multilevel Approach. In Gazzola, Michele and Wickström, Bengt-Arne (eds) The Economics of Language Policy. Cambridge, MA and London, UK: MIT Press, pp. 225–264.

- Mazrui, Ali A. and Mazrui, Alamin M. (1998) The Power of Babel: Language and Governance in the African Experience. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p. 114.

- Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.) (1999) Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 355.

- Ibid.

- Wolff, Ekkehard (2000) Language and Society. In Heine, Bernd and Nurse, Derick (eds) African Languages: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 301.

- Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.) (1999), p. 354.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 356.

- It is only very recently that the coalition rebranded itself into the “Biltsigina” (Prosperity) Party, claiming to be a pan-Ethiopian party surpassing the ethnic divide. The political modus operandi, however, does not show a fundamental departure.

- Delanty, Gerad (1996) Beyond the Nation-state: National Identity and Citizenship in a Multicultural Society – A Response to Rex. Sociological Research Online, 1 (3), p. 1.

- Wolff, Ekkehard (2017) Language Ideologies and the Politics of Language in Postcolonial Africa. Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus, 51, pp. 1–22.

- Lewis, Paul M. (2015) Ethnologue: Languages of the World (18th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. Available at: <http://www.ethnologue.com>.