Introduction

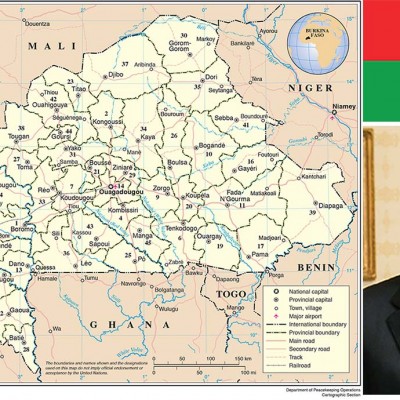

Since 2006, there has been much effort exerted towards integrating peacebuilding as a component of key policies and strategies as well as development programmes in post-conflict countries. This idea became acceptable to the Liberian government as a means to institutionalise peacebuilding following efforts by the United Nations (UN) to work with post-conflict countries, either within the specific mandates of UN military missions or through the UN’s Peacebuilding Architecture. Beginning in 2006, the mandates of most military missions shifted to incorporate peacebuilding as a key element. Likewise, Statement of Mutual Commitments (SMCs) and/or Peacebuilding Priority Plans (PPP) have been developed and adopted, both by governments and the UN, to provide peacebuilding support to post-conflict countries. The SMCs and PPPs, in most cases, have been developed based on conflict analysis involving multiple actors, and intended to help address the root causes of conflict and potential conflict triggers.

This article intends to contribute to ongoing discussions on institutionalising peacebuilding, with a focus on Liberia. The article sets the premise that in order to foster the link between security and emergency programming, including longer-term development and sustained peace, especially in post-conflict countries, peacebuilding elements need to be infused into policies and programmes. In this regard, the article discusses efforts by the government of Liberia to integrate peacebuilding as a component of policies and frameworks as well as development programmes.

First, the article examines efforts to integrate peacebuilding in the policy frameworks of the government – particularly the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS), the Liberia Medium Term Economic Growth and Development Strategy, the Agenda for Transformation and the Liberia Peacebuilding Programme (LPP), with its dual focus on justice and security and national reconciliation. The article highlights that the efforts of the government to infuse peacebuilding approaches within its policies and frameworks have been supported – if not guided – by earlier attempts of the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) to integrate peacebuilding as a key element of the mission’s mandate. Second, the article emphasises that effective peacebuilding must be a strategic process entailing the synergetic and standardised application of a series of multidimensional actions targeted at identifying and removing the sources of conflict and identifying and supporting structures and capacities for peace. Finally, the article identifies some challenges to integrating peacebuilding within policy frameworks, and concludes with suggestions for identifying a strategic direction that institutions in Liberia and elsewhere can take to ensure an integrated and sustainable approach to peacebuilding, especially in the context of peace consolidation.

Liberian Efforts to Integrate Peacebuilding in Policy Frameworks

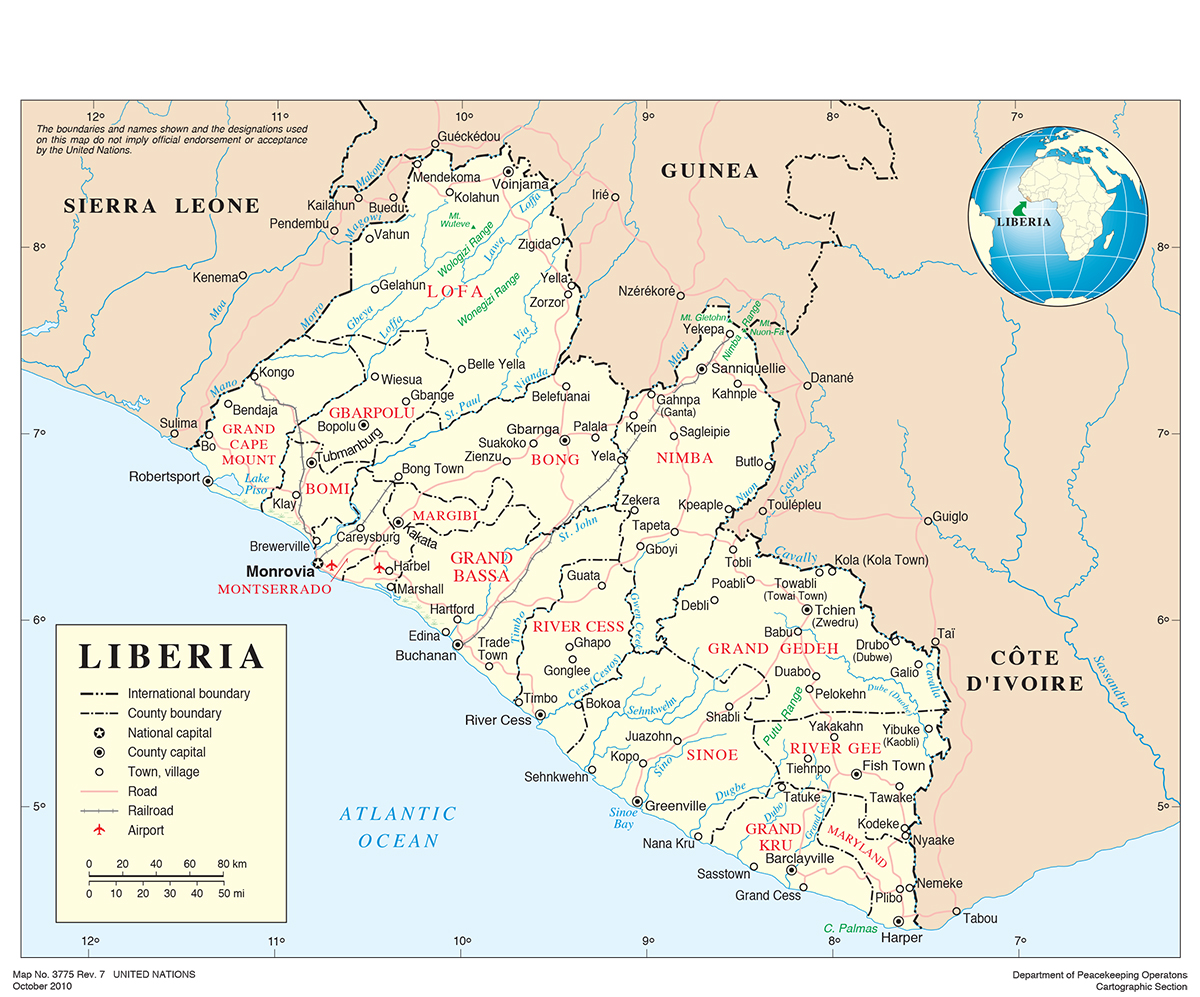

Since 2006, the government has recognised the importance of institutionalising peacebuilding within the strategic policy frameworks of post-conflict settings, and has taken practical steps in this regard. For example, the government’s PRS (2008–2011) identified the sources of conflict and polarisation in Liberia and highlighted a number of conflict factors, with appropriate interventions to address them over the PRS implementation period. In addition, the government has developed programmes and frameworks – including the LPP; the Justice and Security Joint Programme; the Strategic Roadmap for National Healing, Peacebuilding and Reconciliation; and the National Security Strategy – which not only identify the root causes of conflict and conflict drivers but also propose interventions to mitigate or address the pervasive conflict issues that cut across Liberia. Also notable in this effort is the establishment of the Liberia Peacebuilding Office (PBO), attached to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as the main government office for coordinating various peacebuilding initiatives.

The process of integrating peacebuilding within government policies and programmes took its cue from previous efforts by UNMIL to integrate peacebuilding within key policy frameworks of the mission. In 2005, following the establishment of the UN Peacebuilding Commission,1 both the role of peacekeeping missions and UN specialised agencies in post-conflict peacebuilding evolved to consider peacebuilding as an integral component of peacekeeping. Policy discussions in UNMIL were guided by the premise that the development of integrated peacebuilding strategies to inform the work of the UN in field operations would constitute good practice for durable peace and stability.

In Liberia, UNMIL’s mandate progressively included key aspects of peacebuilding, especially following the inauguration of a democratically elected government in January 2006. Priority tasks set out in the 10th Progress Report of the Secretary-General to the UN Security Council (UNSC) broadly included security, recovery and development imperatives. Resolution 1712 (2006) further called upon the Secretary-General to keep the UNSC informed with respect to progress on the facilitation of ethnic and political reconciliation, among other duties. The series of actions undertaken by UNMIL to integrate peacebuilding into strategic policy frameworks were underpinned by sound conflict analysis that specified the root causes of conflict, including a full appreciation of the interaction of factors and forces that drove the conflict. This analysis helped to identify pivotal structures and institutions, with a view to strengthening their capacities for peace.2

The inclusion of peacebuilding as a component of peacekeeping interventions was based on research findings at the time, which showed that a high percentage of post-conflict states erupted into violence after a peace agreement was reached.3 This trend was – and, to some extent, is still today – prevalent, particularly in the African context. This is in part because of the complexity of the conflicts involved, most of which feature transborder militarisation, shifting alliances and unorganised, heterogeneous militias that create complex post-conflict power-sharing dynamics, as well as large youth populations in an environment with minimal educational and livelihood opportunities, but flush with weapons. The recent crises in Guinea-Bissau and South Sudan are examples.

In November 2005, UNMIL established the Joint Peacebuilding Framework. This was a ‘seven-pillar’ framework for action that identified priority areas of support to the incoming government under four pillars: Peace and National Security, Good Governance Rule of Law, Economic Revitalisation, and Infrastructure and Basic Services. In June 2006, UNMIL and other UN agencies in Liberia published the Common Country Assessment, which represented a holistic analysis by the UN of the situation in Liberia with regard to peace, security, development and human rights. The Common Country Assessment identified seven conflict factors and presented nine interdependent challenges to peacebuilding and development, and cross-cutting imperatives, and suggested priority areas for action.4

By October 2006, UNMIL had developed the Integrated Mission Priorities and Implementation Plan – a framework that represented the UN’s mandate and strategic direction, and synthesised the objectives of key UN planning documents.5 In May 2007, the UN Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) was produced for an integrated programmatic response of the UN – mainly the specialised agencies, funds and programmes of the UN Country Team and the Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy (I-PRS) of 2007. The UNDAF also became a tool for achieving a ‘One UN’ approach.6

It is also worth noting the significant contributions of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in helping to ensure that the government’s peace and development policies considered the conflict dimension of poverty as well as conflict sensitivity in the implementation of these policies and strategies. In 2007, these institutions provided training for the I-PRS technical team, and provided suggestions to help strengthen both the I-PRS and PRS through what was referred to as the Joint Staff Advisory Note. The Joint Staff Advisory Note of July 2010 noted, for instance, on the peacebuilding and conflict sensitivity theme, the importance of a well-managed decentralisation process to reduce the urban–rural divide and expand the opportunities for democratic participation, among others.

While Liberia is currently in its 12th year of peace since the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was signed in 2003, peacebuilding activities remain a critical complement to development goals and policies. Consequently, a number of key policy documents – including the National Vision (Liberia Rising 2030), the National Reconciliation Roadmap and the Agenda for Transformation – highlight the conflict factors capable of mobilising groups into renewed violence, to identify priority areas for peacebuilding activities.7

Key Policy Instruments

The key policy instruments in Liberia include the PRS, the Liberia Peacebuilding Programme, the Agenda for Transformation and the Reconciliation Roadmap.

Poverty Reduction Strategy

One of the key policy instruments of the Government of Liberia is the PRS, developed in 2008. It not only described the “origin of conflict and polarization in Liberia” but also highlighted six root causes of conflict, all of which remain areas of conflict.8 The government has emphasised the importance of building the capacities of leaders, both at national and subnational levels, in conflict-sensitive approaches to policymaking and the implementation of development programmes. With this, the government maintained, it would be laying the foundations for sustainable peace and development.9 The government also included within the PRS a number of interventions intended to address these conflict factors over time.

Table 1 shows a few conflict factors mentioned in the PRS, with interventions to address them.

Table 1: Conflict Factors and Interventions

| Conflict Factors | Government’s Interventions |

| Poor leadership and misuse of power |

|

| Weak justice system |

|

| Identity based divisions and lack of shared national vision |

|

| Mismanagement of natural resources |

|

The Liberia Peacebuilding Programme

In September 2010, Liberia became formally engaged with the Peacebuilding Commission. An SMC was subsequently adopted in November 2010 by the Peacebuilding Commission and the government, highlighting three key peacebuilding priorities: supporting security sector reform, strengthening the rule of law and promoting national reconciliation. In May 2011, the LPP was approved, after being developed as a programmatic framework for achieving the commitments and targets in the SMC.10 The LPP highlights the three peacekeeping priorities in two components: (1) justice and security, and (2) national reconciliation. Also in 2011, a Justice and Security Joint Programme was developed to implement the first component of the LPP. The Justice and Security Joint Programme is intended to address three of the key conflict factors identified, including the weak security sector, the dysfunctional justice system, and the exclusion of the rural population from adequate justice and security services. The key focus of the Justice and Security Joint Programme is the construction of five justice and security regional hubs across Liberia, intended to provide a decentralised and holistic approach to security and justice service delivery. The hub concept is also a means by which national agencies can provide effective security for Liberia on a sustained basis, after UNMIL withdraws from Liberia in 2016.

The Agenda for Transformation

Following a three-year period (2008–2011) of intensive consultations in the diaspora, the government held a national stakeholders conference in December 2012, intended to endorse the National Vision – the Liberia Rising 2013 document. Among other elements, the National Vision strategises a two-pronged approach to achieving the vision:

- a focus on the ‘hardware’: infrastructure (power/energy and roads); people (youth skills development and employment, reconciliation, health improvement, education/manpower development and social safety net provision); and institutions (security, private sector development, and public sector institutions); and

- a focus on the ‘software’: including conflict issues, social cohesion and reconciliation.

However, despite the Agenda for Transformation being focused primarily on economic growth, its first chapter focuses on peace, security and the rule of law.

The Reconciliation Roadmap

The Reconciliation Roadmap was developed and launched in 2012, and complements other peacebuilding-related programmes – but with a slight focus on addressing conflict drivers through 12 thematic areas, separated into three broad categories.11 The Roadmap aims to achieve three inter-related goals:

- transforming individual, community and societal mindsets;

- rebuilding and strengthening intergroup relations; and

- dismantling and replacing polarising institutions with more inclusive institutions as a safeguard to not return to civil war.

These goals strive to consolidate the various forces that continue to foster a degree of discontent and divisiveness in Liberian society.12

Another key policy instrument is the National Security Strategy for the Republic of Liberia (NSSRL). The primary purpose of this instrument is to identify key security challenges, develop a national security coordination mechanism, and establish a holistic approach to security with sustainable architecture. While the NSSRL is unsurprisingly focused on the security sector, it also offers a comprehensive analysis of conflict factors affecting Liberia’s national security environment, separated into three categories and listed in order of priority and urgency: internal, regional and global.13

Although this article focuses on the efforts of the government with support from the UN, it is worth mentioning that civil society organisations (CSOs) have played a critical role in these efforts. These CSOs include the Interfaith Mediation Council, the Mano River Women in Peace Network, the Liberia Women Initiative, the New Africa Research and Development Agency, and the West Africa Network for Peacebuilding. In addition, several CSOs have contributed immensely to the development of various peacebuilding-related policies and strategies, and have mobilised grassroots support and participation for the implementation of peacebuilding efforts through the Liberia non-governmental organisation network and the National Civil Society Council of Liberia.

Challenges to Integrating Peacebuilding

First, as the Liberian experience has shown, sometimes post-conflict governments are apprehensive as to what the peacebuilding process entails. Some governments are weary of prioritising and sequencing what is often orchestrated by the international community for post-conflict countries: peacebuilding, early recovery, reconstruction and development. In the case of the Government of Liberia, the formulation of a 150-Day Action Plan soon after assuming power was the earliest signal of the government’s eagerness to move beyond relief into full-scale recovery and development. Therefore, infusing conflict issues into government policies and development programmes, or developing a full-scale strategy for peacebuilding, could not find political space.

Second, since peacebuilding is a quintessentially political question, it was difficult terrain for the Liberian authorities, as it required a re-examination of past legacies; the character, and nature of, the interaction between formal, informal and traditional systems; who the players are, and what they stand to gain or lose from change; and so on. Consequently, much of the analytical work from 2003 – such as the Results-focused Transitional Framework – did not delve into the root causes of the Liberian conflict and its key drivers (unemployment, social exclusion, and so on). These root causes were instead relegated to a secondary position, in favour of mainstream sectors such as health and education.

Third, besides political will, there was also the question of capacity to develop, adopt or mainstream peacebuilding into programming itself. Inculcating peacebuilding elements in policies and development programmes requires continuous engagement with policymakers, as well as providing moral, technical and financial support where necessary.

In practice, while many aspects of peacebuilding have been undertaken as part of the UN’s post-conflict interventions – and on the part of the government – to integrate peacebuilding in policies and frameworks, these approaches have often been characterised by a lack of strategy, coordination and complementarity between actors and institutions. Many key actors seem not to be on par with this emerging trend and, in some cases, it is difficult to get their commitment. In some instances, this has served to impede operational progress and, ultimately, prevent sustained results.

Conclusion

This article has discussed the integration of peacebuilding in policy and strategies. It has also highlighted efforts on the part of the Liberian government, with support from the UN, and notes the importance of identifying the root causes of conflict and factoring their role into decision-making on programming and policymaking towards preventing future conflict.

However, there are some limitations, as the Liberian case demonstrates: the linkages and synergies anticipated from the interactions of measures across peacebuilding dimensions are sometimes overlooked, and this ultimately lies at the heart of the challenge in producing integrated strategies. In addition, some of the key policy documents discussed did not propose an operational framework or methodology for how policy choices could be made in ways to ensure conflict sensitivity. This is also true for the Reconciliation Roadmap, which mentions conflict sensitivity as a guiding principle for implementation – but it is not clear how to infuse conflict-sensitive approaches within the programmes developed to implement the 12 thematic areas in the Roadmap. In their rationale and proposed methodologies, both the Agenda for Transformation and Roadmap do, however, highlight some practical steps to address various conflict factors in the listed interventions. This, however, can only adequately serve peacebuilding, if undertaken effectively.

Notwithstanding, these earlier efforts at integrating and institutionalising peacebuilding have made some tangible gains, and are useful for the implementation of the National Vision – Liberia Rising 2030, and in future endeavours. In addition, efforts must be exerted to galvanise and mobilise the support and participation from the vast majority of the citizenry in the implementation of peacebuilding and reconciliation programmes.

Endnotes

- The UN Peacebuilding Commission was established in 2005 under the UN Peacebuilding Architecture. The Commission provides political accompaniment, and mobilises technical support and resources for countries on the Commission’s Agenda.

- Developed by Johan Galtung in 1975, the concept of peacebuilding found its way into UN discourse with former Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s 1992 Agenda for Peace. Referred to as “actions to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid a relapse into conflict”, peacebuilding was viewed as measures undertaken immediately after peacekeeping to establish frameworks and structures for a transition to a more stable and secure society. See Call, Charles (2005) ‘Institutionalizing Peace: A Review of Post-conflict Concepts and Issues for DPA’, Consultant Report, 31 January.

- Gray-Johnson, Wilfred N. (2009) Approach to Post-conflict Peacebuilding in Africa: The Mission in Liberia. Conflict Trends, 3 (2009), p. 12.

- United Nations (2006) United Nations Common Country Assessment in Liberia. June, p. 8.

- This framework suggested focusing on a number of government institutions (for example, the Liberia National Police) or critical sectoral areas (for example, the justice sector), and thematic issues (for example, corrections and human rights) and specific activities to achieve expected outcomes.

- The One UN Approach advances coordination mechanisms among various UN Agencies and UNMIL in support of government peace, security and development priorities.

- In 2010 (revised in 2014), the Liberia Peacebuilding Office undertook a comprehensive desk review of 15 policy-related documents, including conflict-mapping reports. Overall, a total of 17 conflict factors are identified across the 15 documents examined. A few of these conflict factors are identified in Table 1.

- Government of Liberia (n.d.) Poverty Reduction Strategy, 2008–2011, pp. 14–15.

- Ibid., p. 21.

- The SMC is more a policy framework that highlights a number of commitments, as well as targets to be met over a five-year period both by the government and the Peacebuilding Commission, while the LPP is a programmatic framework for actualising the SMC.

- A) Accounting for the Past: 1. Palava Hut Process of Addressing Past Wrongs, 2. Memorialisation, 3. Reparation 4. Diaspora and Reconciliation; B) Managing the Present: 5. Political Dialogue, 6. Conflict Prevention and Mediation, 7. Women’s Recovery and Empowerment 8. Children and Youth Recovery and Empowerment, 9. Psychosocial Recovery and Empowerment for Persons with Disabilities; and C) Planning for the Future: 10. Inclusive People’s History and Collective Identity, 11. Transformative Education System and 12. Constitutional and Law Reforms.

- The roadmap argues further that genuine peacebuilding and reconciliation in Liberia must usher in a new and reconciled beginning, which should be facilitated by public acknowledgement and accounting for individual and collective responsibilities, offering public apology, committing to the short- and long-term reparation of victims and their communities, and addressing ongoing ethnic and land-based conflicts. It must ensure policies and actions are conflict-sensitive and deliberately seek to foster social cohesion and nation-building.

- The principal conflict factors identified by the NSSRL include: land and property disputes; youth vulnerability and exclusion; nascent democracy and issues with ensuring civilian control of security forces; lack of respect for the rule of law; poverty and food insecurity (particularly emphasising the lack of livelihood opportunities for ex-combatants and servicemen); the regional dimension, including porous national borders, regional instability and high youth unemployment; overcentralisation of power; global issues such as international crime and terrorism; a dependent economy; and a weak security sector.