Introduction

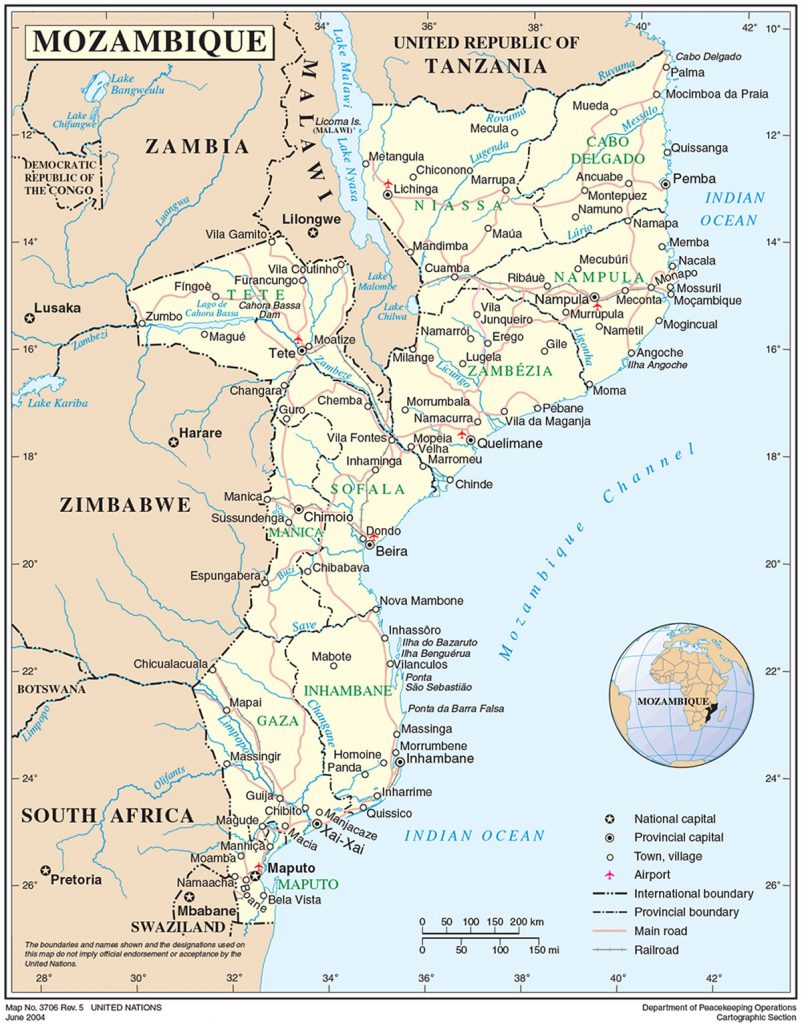

Since early October 2017, when the Islamist militants or jihadists – identified as the Ansar al-Sunna – launched their first attacks in the villages and towns of Mozambique’s northern province of Cabo Delgado, insurgency and conflict has continued to escalate, targeting civilians, public infrastructure and government buildings. Although the Government of Mozambique continues to make concerted efforts to fight and subdue the terrorist insurgency through its national defence forces, the Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique (FADM), a series of battles with the terrorist militants has resulted in widespread violence, insecurity, the death of over 2 400 people[1] and the displacement of over 500 000 civilians by the end of November 2020.[2] It has also disrupted economic activities, especially farming, thereby worsening food insecurity.

It is now four years since the first attack in Mozambique was launched by Islamist militants on 5 October 2017. Mozambique requested assistance and support from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states at the SADC Extra-Ordinary Organ Troika Summit of Heads of State and Government, held in Harare, Zimbabwe, on 19 May 2020, to fight against the terrorist insurgency in northern Mozambique.[3] So far, the regional body has not intervened to assist in managing and resolving the conflict. Instead, SADC member states, at their 40thOrdinary Summit of Heads of State and Government meeting in August 2020, only “expressed solidarity and commitment to support Mozambique in addressing the terrorism and violent attacks”.[4] At the SADC Extra-Ordinary Organ Troika Summit held on 27 November 2020 in Gaborone, Botswana, the regional body again “noted with concern” the ongoing insurgency in Cabo Delgado, and “expressed continued SADC solidarity with Mozambique”.[5]Although the summit directed the urgent “finalization of a comprehensive regional response and support” to Mozambique,[6] no concrete action has been taken thus far. This is despite the fact that the terrorist insurgency in Mozambique has the potential to cause instability and insecurity in the region, and that one of the objectives of SADC, as stated under Article 5 of the SADC Treaty of 1992, is “to promote peace and security”.[7]

This article will therefore examine the role that SADC can play in managing and resolving the insurgency and conflict in Mozambique. In doing so, the analysis focuses on the need, rationale, justifications, nature and form of interventions, as well as the possible nationwide and region-wide implications of such interventions.

Background and Origins of Conflict and Insurgency in Mozambique

The terrorist insurgency in Mozambique is traced to 5 October 2017, when 20 armed members of the Ansar al-Sunna attacked three police stations (a police command, a natural resources and environment police patrol station, and a police post) in a pre-dawn raid in Mocímboa da Praia, a coastal district in Cabo Delgado Province.[8] The attackers, who spoke Portuguese, Kiswahili and Kimwani (a language widely spoken along the coast of Cabo Delgado Province), killed two policemen during the raid.[9]

It has been reported that Ansar al-Sunna (Helpers of Sunnah) is driven by Islamic fundamentalism. Sunnah(“habitual practice” in Arabic) generally refers to traditional and legal customs of the Islamic community. Some refer to the group as Ahlu Sunna Waljama’a (ASWJ) – itself a name associated with an Islamic paramilitary group based in Somalia that opposes hardline and radical Islamist groups such as Al-Shabaab – whilst there has been footage where the insurgents claim that they belong to the “Islamic State Central Africa Province” (IS-CAP). Thus, Ansar al-Sunna in Mozambique is made up of Islamic fundamentalists who are Mozambicans from the districts of Mocímboa da Praia, Palma and Macomia, together with foreign nationals from Somalia and Tanzania. The insurgent group continues to recruit members locally, as militias.

Different theories and explanations attempt to locate the root causes and origins of the insurgency. Like many terrorist groups, the insurgents have no public face. The dominant argument has been that the insurgency in Mozambique has been instigated by poverty, lack of socio-economic opportunities, marginalisation, discrimination, inequality and the frustrations of young people as a result of prolonged and unresolved conflict in the country. In 2017, when the first insurgent attacks were recorded, Mozambique’s economy was experiencing a slowdown. The gross domestic product (GDP) growth was 3.8% in 2016 and 3.7% in 2017, compared to an average growth of 7.3% in the previous 10 years.[10] Mozambique’s overall public sector debt accounted for 112% of the country’s GDP in 2017 – way above debt sustainability thresholds.[11] In terms of poverty prevalence, 46.1% of the population was living below the poverty line in 2017.[12] Economic governance deteriorated, with the country recording a decreasing score of 3.3 in 2017, down from 3.6 in 2017, as ranked by the African Development Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment. This was below the continent’s average, itself a reflection of the poor quality of economic policies and institutions.[13] Youth unemployment was 41.7% in 2017.[14] Only 29% of the national population had access to the electricity grid, whilst only 20.5% of the population had access to safely managed sanitation facilities.[15] Almost 20% of the population was food insecure and 25% of the population experienced hunger or malnourishment in 2017.[16]

Given the high inequality in Mozambique, the economic reality was consistent with the relative deprivation theory, often attributed to sociologist Robert Merton, which explains that revolutions and social movements occur when poor masses are deprived.[17] This is relevant, considering that Mozambique is rich in resources, with vast mineral deposits that include coal, iron ore, tantalum, titanium, copper, bauxite, lithium and gold, as well as the newly discovered natural gas reserves in Rovuma Basin, which have the potential to transform the country into a significant exporter of liquified natural gas (LNG). By 2017, Mozambique was among the most unequal countries in the world, with a Gini Co-efficient Index of 54%, and also ranked 180 out of 189 countries in the world in terms of human development.[18] The possibility that Cabo Delgado may have turned into a theatre of natural resource-curse wars – as has been the case in most resource-rich countries and regions – cannot be dismissed. When the estimated 180 trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves were discovered off the coast of northern Mozambique (which is second in size only to Nigeria and Algeria), resulting in a US$20 billion financial investment decision in 2019, there was a stampede of oil and gas exploration companies including Total, ExxonMobil, ENI, Shell and China National Petroleum Corporation. This, coupled with frustrations and political discontent due to perceived delayed delivery of proceeds from natural gas exploitation, may have provided fertile ground for the manipulation (by elites) of local grievances and dissatisfaction with public procurement and investment decisions in Cabo Delgado.

There are, however, other explanations that the insurgency in Mozambique has been instigated by Muslims radicalised by preachers from Kenya and Tanzania, whilst others attribute this to the conservative Islamism (Wahhabism) of Mozambican students who studied in Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Sudan.[19]

The Implications of Insurgency in Mozambique

The insurgent group has engaged in several raids on homes, villages and communities in Cabo Delgado Province, resulting in communities abandoning their homes for security reasons. The majority of people have sought refuge in some parts of Mocímboa da Praia town, other safer parts of the province and in the neighbouring provinces of Nampula, Niassa and Zambezia. As of 8 December 2020, there were 711 violent attacks by the insurgency, according to estimates from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED).[20] Given the nature of terrorism and insurgency, it is highly probable that numerous attacks in Cabo Delgado go unreported; hence, the ACLED estimates may be an underestimation.

As is the case with most terrorist groups, Ansar al-Sunna has used several unconventional warfare tactics and strategies. The insurgents have attacked civilians and used gruesome killing methods, such as decapitating and burning victims. They have also burned houses, pillaged the properties of fleeing families, destroyed public infrastructure facilities, targeted vehicles and stolen firearms and ammunition from national security forces.[21] Based on various reports from the media, police and government, there are a significant number of affected villages and communities in Cabo Delgado,[22] with civilians (including women and children) having been kidnapped, killed, injured or displaced, and properties either pillaged or burnt.

Attacks and raids by the terrorist militia have also extended to public infrastructure and business operations. On 21 February 2019, for example, suspected insurgents attacked Anadarko Petroleum Corporation on two occasions in the town of Palma in Cabo Delgado, killing one worker and injuring several others.[23] Anadarko Petroleum Corporation, a United States petroleum and hydrocarbon exploration company, led the LNG project on the Indian Ocean coast before it was replaced by Total at the end of 2019. There were also reports that a company vehicle for Fenix Construction Services, a construction firm subcontracted by Total South Africa on the Mozambique LNG project, was ambushed by insurgents just outside Mocímboa da Praia town on 27 June 2020, and eight workers were killed.[24] The national power utility company, Electricidade de Moçambique (EdM), had a repair truck ambushed in Muidumbe District by insurgents on 28 September 2020, as its workers attempted to repair power lines that had been cut by the insurgents. The workers were captured and injured before being released.[25] Another EdM worker was killed by suspected insurgents in Awasse in September 2020, whilst a primary school was vandalised and a hospital burnt in September 2019.[26] The insurgents captured the district capital of Quissanga and the town of Mocímboa da Praia – including the connecting roads to the towns – in March 2020[27], and the strategic port of Mocímboa da Praia in August 2020.[28] Thus, the insurgency in Mozambique continues to affect national peace, security, safety, livelihoods of the people, economic activities, and national development projects and programmes.

Due to the escalating violence and displacement of civilians caused by the terrorist militias, the Government of Mozambique dispatched its national defence and security forces to fight the insurgency. These include the FADM, the Mozambique Republic Police (PRM), the Rapid Intervention Unit and the National Criminal Investigative Service (especially the Counter-Terrorism Unit). The national defence and security forces have recorded both victories and casualties in the asymmetric warfare and counterinsurgency against the terrorists. For example, on 29 October 2020, the PRM Commander-General reported that they had pursued and killed 108 terrorists in Cabo Delgado, and had seized huge quantities of war materials from the terrorists in the “past 72 hours”.[29]

The insurgency has had far-reaching implications within the social, economic, humanitarian and political spheres. What is undeniable is the fact that Mozambique has not yet been able to contain and subdue the insurgents, as they need more capacity in terms of training, military intelligence, reconnaissance and equipment. It is against this background that the role of SADC is not only unavoidable but also obligatory, consistent with the SADC Treaty and other relevant SADC and African Union (AU) instruments. Other compelling security and political factors also warrant SADC intervention in Mozambique.

The Role of SADC: Rationale, Justification and Implications

Given the state of insurgency in Mozambique, especially the rising death toll, kidnapping and displacement of civilians, human rights abuses of people in the hands of insurgents, disruption of economic activities and the potential that the continued insurgency will have on the LNG project in Cabo Delgado, there is sufficient basis and justification for SADC to intervene.

SADC has at its disposal a number of instruments to facilitate an intervention: the SADC Treaty of 1992; the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security of 2001, and the SADC Common Agenda (as amended in 2009); the Strategic Indicative Plan for the Organ on Defence, Politics and Security (SIPO); and the SADC Mutual Defence Pact of 2003. The structures and institutions that can be used include the Summit of Heads of States or Government; Council of Ministers; Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation (OPDSC); and the Troika.

There are four crucial factors that constitute the justification for SADC to intervene in Mozambique. First, SADC member states have a legal and moral obligation to assist another member state facing security threats and challenges. One of the objectives of SADC, as stated under Article 5 of the SADC Treaty of 1992, is “to promote peace and security”.[30] On the other hand, under Article 2, the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security also provides that the OPDSC shall “protect the people and safeguard the development of the region against instability arising from the breakdown of law and order, and intra-state conflict”.[31] It further obligates the OPDSC to “prevent, contain and resolve inter- and intra-state conflict by peaceful means” as well as to allow for cooperation between police and state security services to promote “community-based approaches to domestic security”.[32]

By November 2020, the insurgency in northern Mozambique had resulted in the death of over 2 400 people, the displacement of over 500 000 civilians, disrupted economic activities and worsened food insecurity.[33] In addition to this, there is a humanitarian crisis in northern Mozambique as displaced civilians – especially children (who constitute 45% of displaced people), the elderly, women and girls, people living with disabilities, and people living with HIV/AIDS – face protection risks and are exposed to exploitation.[34] It has also been reported that 10% of these internally displaced persons (IDPs) are staying in collective sites, which are overcrowded and have limited access to safe shelter, water and sanitation facilities.[35] The intrastate conflict in Mozambique therefore qualifies and satisfies the conditions under which SADC is obliged to intervene in member states, as provided under in the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security. Article 11(2)(b) of the Protocol provides that the SADC OPDSC shall seek to resolve “large scale violence between sections of the population, or between the state and sections of the population” and “a condition of civil war or insurgency”.[36] Thus, SADC not only has a legal basis to intervene in Mozambique, as provided for under its own legal instruments, but also has moral justification to assist Mozambicans as they continue to be exposed to death, kidnapping, abuse, displacement and all the effects of insecurity and instability posed by the insurgents. In addition, the country is facing the ramifications of COVID-19, having recorded 17 002 cases and 143 deaths as of 15 December 2020.[37] Mozambique is also yet to fully recover from cyclones Idai and Kenneth of 2019, which claimed 603 lives, injured over 1 600 people, destroyed over 200 000 houses and left 3.8 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in the provinces of Zambezia, Sofala, Manica, Tete and Inhambane.[38]

Second, SADC member states are legally obligated to honour commitments that they have made at the continental level under the AU through various instruments. These include the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Resolution on the Strengthening of Cooperation and Coordination among African States (1992), the OAU Declaration on the Code of Conduct for Inter-African Relations (1994), the OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism (1999), the AU Plan of Action for the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism (2002), and the AU Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism (2004), which all call for African states to cooperate in combating terrorism and insurgency through collective and collaborative approaches. Although only three SADC member countries (Lesotho, Mozambique and South Africa) have ratified the AU Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism (2004), and only five SADC member countries (Botswana, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eswatini, Zambia and Zimbabwe) have not ratified the OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism of 1999, the Protocol and the Convention entered into force in 2014 and 2002 respectively.[39] SADC member states are therefore legitimately expected to honour the letter and spirit of these AU commitments and intervene in Mozambique, in line with the pacta sunt servanda principle of international law. Moreover, SADC member states, being member states of the AU, agreed in 2013 to cooperate in ending all wars, civil conflicts, violent conflicts and human rights violations under “Silencing the Guns in Africa by 2020”, one of the flagship projects of the AU’s Agenda 2063.

Third, the Government of Mozambique has requested assistance and support from SADC member states to assist in fighting insurgency in line with the procedural regularities provided for under Article 11(4) of the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security. This was done officially at the SADC Extra-Ordinary Organ Troika Summit of Heads of State and Government held in Harare, Zimbabwe, on 19 May 2020.[40] However, there appears to be indifference or lack of political will to intervene on the part of SADC. Mozambique was requested by the SADC Summit to prepare a roadmap to address insurgency in Cabo Delgado, for consideration by the SADC Inter-State Defence and Security Committee (ISDSC) and Inter-State Politics and Diplomacy Committee (ISPDC).[41] However, despite the gravity of the matter, it was reported in September 2020 – four months later – that the ISDSC and ISPDC had not met, as they wanted to provide more time to Mozambique “to finalise preparations of the roadmap” and an indication of the required assistance from SADC.[42]

Although there have been allegations that Zimbabwe and South Africa have deployed troops to fight insurgency in Mozambique, the Government of Zimbabwe has dismissed such news as fake and stated that it has not done so,[43] whilst the Government of South Africa has neither confirmed nor denied such allegations, even after Parliamentary probing.[44] Instead, the South African Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor, stated that South Africa was ready to assist Mozambique with intelligence services or military upon request, adding that SADC had requested Mozambique to provide a roadmap on the nature of assistance needed before a decision on the course of action is considered.[45] What is worrying is that despite the existence of the SADC Mutual Defence Pact of 2003, which facilitates mutual cooperation in defence and security matters, Mozambique is now looking for help beyond SADC, and has requested humanitarian, logistical and capacity-building assistance from the European Union (EU) to fight the insurgency.[46] Further, there are indications that the Wagner Group/Grupa Vagnera – a Russian private paramilitary organisation that is believed to be an arms-length unit of the Russian Ministry of Defence – is reportedly providing military aid, combat troops and military equipment to Mozambique to prop up the anti-terrorism fight.[47]

Fourth, SADC has to intervene in Mozambique, since the insurgency may threaten regional peace and security. Article 11(2)(b) of the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security justifies the basis for SADC intervention if “a conflict threatens peace and security in the region or in the territory of another state”.[48] Given the trend, nature and intensity of the insurgency in Mozambique, there is a reasonable basis to suggest that this may spill into neighbouring SADC countries if not addressed, especially those countries contiguous to Mozambique, namely Zimbabwe, Tanzania, South Africa, Eswatini, Zambia and Malawi. Already, South Africa has made it clear that Mozambique may destabilise the region, reverse regional peace gains and dividends, increase the inflow of IDPs into South Africa and neighbouring countries, and disrupt possibilities of South Africa importing natural gas from Mozambique.[49] There are security risks and challenges for SADC countries, as they fear reprisals from the insurgents if they intervene in Mozambique. Perhaps, this is why most of the bilateral and even regional engagements between Mozambique and SADC are highly classified and confidential. For example, there have been communications from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant/Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which is linked to the insurgents, to the effect that if South Africa intervenes in Mozambique, it would “open the fighting front” within South Africa’s borders.[50] However, experiences with insurgency and terrorism elsewhere in Africa (such as Boko Haram in Nigeria; Al-Shabaab in Somalia; Ansar Dine in Mali; Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in Algeria, Mali and Niger; Ansar al-Shari’a in Benghazi and ISIS in Libya; Islamic State West Africa Province in Nigeria and Lake Chad region; and others) present instructive lessons to Africa on how terrorist and insurgent groups easily expand their networks and recruitment base, as well as scale up their sophistry and radicalise, if they are not contained in their infancy. Insurgents in Mozambique reportedly carried out cross-border raids in the village of Kitaya in Tanzania’s Mtwara region on 14 October 2020.[51] This prompted Tanzanian authorities to sign a memorandum of understanding with Mozambique to facilitate security cooperation along the common border. For SADC, a stitch in time may save nine, to defuse the insurgency in Cabo Delgado before it spreads across the region.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The insurgency in Mozambique is escalating and its political, security, humanitarian and cross-border implications are far reaching. This has tested the efficacy of established SADC norms and response frameworks, as well as the commitment of the regional body to its instruments, especially the SADC Treaty; the SADC Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security; the SADC Common Agenda; SIPO; and the SADC Mutual Defence Pact, as well as commitments made at the AU level to fight terrorism and insurgency. SADC has the legal, moral and security justification to intervene in Mozambique. In terms of scope of assistance, SADC may assist through providing military troops, technical training, intelligence gathering and information sharing, military equipment and maritime security cooperation – especially South Africa, given its military might in terms of technological advancement, combat service support capacity and operational or logistical capability. Diplomatically, SADC also has the latitude to facilitate or mediate negotiations between the Government of Mozambique and identified interlocutors in the insurgent group. Mozambican president, Filipe Jacinto Nyusi, has expressed willingness to negotiate with the insurgents on the condition that they “unmask” themselves.[52] SADC, however, appears to be adopting a measured and unhurried approach. The current chairperson of SADC is Mozambican President Nyusi, whilst the OPDSC is chaired by Botswana’s president, Mokgweetsi Eric Keabetswe Masisi. The Mozambican president may need to leverage on his current chairpersonship of SADC to push for a more swift and rapid response to the crisis in Cabo Delgado.

It is in the interests of SADC to urgently address the insurgency in Mozambique before the insurgents develop a regional terrorist hub and spoke networks, as has been the case in the Sahel region, Lake Chad Basin and the Horn of Africa. The AU may need to put diplomatic pressure on SADC to step up efforts in assisting Mozambique. A conflict-free Mozambique will ensure peace, security and stability in the region, thereby creating a conducive environment for the pursuit of the SADC vision for socio-economic development and transformation.

Dr Clayton Hazvinei Vhumbunu is a Technical Officer at Rhodes University, Faculty of Humanities (Public Service Accountability Monitor) in Grahamstown, South Africa.

Endnotes

[1] Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (2020a) ‘Cabo Ligado Weekly: 30 November–6 December 2020’, 15 December 2020, Available at: <https://acleddata.com/2020/12/08/cabo-ligado-weekly-30-november-6-december/> [Accessed 15 December 2020].

[2] United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) (2020) ‘Global Humanitarian Overview 2021. Part Two: Inter-Agency Coordinated Appeals’, November 2020, Available at: <https://gho.unocha.org/mozambique> [Accessed 15 December 2020].

[3] Southern African Development Community (SADC) (2020a) ‘Extraordinary Organ Troika Plus the Republic of Mozambique Summit of Heads of State and Government’ – Harare, Zimbabwe, 19 May 2020, p. 2, Available at: <https://www.sadc.int/files/9315/8991/2199/Communique_of_the_Extraordinary_SADC_Organ_Troika_Summit_held_on_19_May__2020.pdf> [Accessed 18 October 2020].

[4] SADC (2020b) ‘40th Ordinary Summit of the Heads of State and Government’, 17 August 2020, p. 4, Available at: <https://www.sadc.int/files/8115/9767/2537/Communique_of_the_40th_SADC_Summit_August_2020_-ENGLISH.pdf> [Accessed 19 October 2020].

[5] SADC (2020c) ‘Communiqué of the Extraordinary Organ Troika Summit Plus Force Intervention Brigade – Troop Contributing Countries, The Democratic Republic of Congo and The Republic of Mozambique, 27 November 2020’, p. 2, Available at: <https://www.sadc.int/files/5116/0649/0216/English-Communique_for_the_Extraordinary_OTS_Plus_Summit_27_Nov_2020.pdf> [Accessed 15 December 2020].

[6] Ibid, p. 2.

[7] SADC (2015) ‘Consolidated Text of the Treaty of the Southern African Development Community’, p. 6, Available at: <https://www.sadc.int/files/5314/4559/5701/Consolidated_Text_of_the_SADC_Treaty_-_scanned_21_October_2015.pdf> [Accessed 20 October 2020].

[8] Frey, Adrian (2017) ‘Armed Men Attack Police Stations in Mocimboa da Praia – AIM Report’, Club of Mozambique, 5 October 2017, Available at: <https://clubofmozambique.com/news/armed-men-attack-police-stations-in-mocimboa-da-praia-aim-report/> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

[9] Ibid.

[10] African Development Bank (2018) ‘Country Results Brief 2018 – Mozambique’, African Development Bank Group, p. 1, Available at: <https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/CRB_Mozambique-En.pdf> [Accessed 25 October 2020].

[11] Santos, Almeida Andre (2018) Mozambique: 2018 African Economic Outlook, African Development Bank Group, p. 5, Available at: <https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents/country_notes/Mozambique_country_note.pdf> [Accessed 25 October 2020].

[12] Ibid., p. 24.

[13] Ibid., p. 2.

[14] Ibid., p. 23.

[15] Ibid., p. 24.

[16] Ibid., p. 9.

[17] Sayles, Marnie (1984) Relative Deprivation and Collective Protest: An Impoverished Theory? Sociological Inquiry, 54 (4), pp. 449–465.

[18] United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2019) ‘Human Development Report 2019: Beyond Income, Beyond Averages, Beyond Today: Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st century’, pp. 302–311, Available at: <http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2019.pdf>[Accessed 20 October 2020].

[19] Morier-Genoud, Eric (2020) The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, Nature and Beginning. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14 (3), p. 397.

[20] Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (2020a) op. cit.

[21] Matsinhe, David H. and Valoi, Estacio (2019) ‘The Genesis of Insurgency in Northern Mozambique’, Institute for Security Studies, Southern Africa Report 27, October 2019, p. 7, Available at: <https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/sar-27.pdf> [Accessed 20 October 2020].

[22] These include Alto Gigone, Banga-Vieja, Bilibiza, Cagembe, Cariaco, Chai, Changa, Chitolo, Chiuba, Columbe, Diaca Velha, Ibo Island, Ida, Ipho, Litingina, Macomia, Maculo, Maluku, Mangwaza, Manilha, Matemo Island, Mecungo Islands, Mitumbate, Monjane, Mucojo, Muidumbe, Nacate, Nagalue, Naliendele, Namaluco, Nantodola, Nathuko, Naunde, Ntapuala, Olumbi, Piqueque, Quirimbas Islands, Rueia, Tapara, Vamizi Islands and Xitaxi. Ibid., pp. 4-5. See also: African Union (2020a) ‘The Monthly Africa Terrorism Bulletin’, African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism Centre/Africain d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Terrorisme, Edition No. 08, 1–31 August 2020, pp. 37–38, Available at: <http://caert.org.dz/Medi-review/Terrorism-bulletin/BULLETIN-Aug-2020.pdf> [Accessed 21 October 2020]; African Union (2020b) ‘The Monthly Africa Terrorism Bulletin’, African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism Centre/Africain d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Terrorisme, Edition No. 07, 1–31 July 2020, pp. 42–43, Available at: <https://caert.org.dz/Medi-review/Terrorism-bulletin/BULLETIN-July-20.pdf> [Accessed 21 October 2020]; and African Union (2019) ‘The Monthly Africa Terrorism Bulletin’, African Centre for the Study and Research on Terrorism Centre/Africain d’Etudes et de Recherche sur le Terrorisme, Edition No. 017, 1–15 September 2019, p. 25, Available at: <https://caert.org.dz/Medi-review/Terrorism-bulletin/BULLETIN%20-%2017.pdf> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

[23] Pilling, David (2019) ‘Anadarko Petroleum Attacked Mozambique’, Financial Times, 22 February 2020, Available at: <https://www.ft.com/content/fcd30100-36d0-11e9-bb0c-42459962a812> [Accessed 24 October 2020].

[24] AllAfrica (2020) ‘Mozambique: Eight Killed in Terrorist Ambush’, 6 July, Available at: <https://allafrica.com/stories/202007060998.html> [Accessed 23 October 2020].

[25] Reliefweb (2020) ‘Cabo Ligado Weekly: 28 September–4 October 2020’, 6 October, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/cabo-ligado-weekly-28-september-4-october> [Accessed 21 October 2020].

[26] United States Department of State (2019) ‘Country Reports on Terrorism 2019’, Bureau on Counterterrorism, p. 28, Available at: <https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Country-Reports-on-Terrorism-2019-2.pdf> [Accessed 23 October 2020].

[27] Fabricius, Peter (2020a) ‘Islamist Insurgents Capture Second Town in Northern Mozambique Within 48 Hours’, Daily Maverick, 26 March, Available at: <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-03-26-islamist-insurgents-capture-second-town-in-northern-mozambique-within-48-hours/> [Accessed 26 October 2020].

[28] Baptista, Andre and Kajjo, Sirwan (2020) ‘Islamist Insurgents Capture Strategic Port in Northern Mozambique’, Voice of America, 13 August, Available at: <https://www.voanews.com/africa/islamist-insurgents-capture-strategic-port-northern-mozambique> [Accessed 26 October 2020].

[29] Club of Mozambique (2020) ‘Mozambique: FDS Announce Killing of 108 Terrorists in Cabo Delgado – Miramar’, 29 October, Available at: <https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-fds-announce-killing-of-108-terrorists-in-cabo-delgado-miramar> [Accessed 25 October 2020].

[30] SADC (2015) op. cit., p. 6.

[31] SADC (2001) ‘Protocol on Politics, Defence and Security of 2001’, p. 3, Available at: <http://www.sadc.int/files/3613/5292/8367/Protocol_on_Politics_Defence_and_Security20001.pdf> [Accessed 26 October 2020].

[32] Ibid, p. 4.

[33] UNOCHA (2020) op. cit.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] SADC (2001) op. cit., p. 12.

[37] Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) ‘Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Latest Updates on the COVID-19 Crisis from Africa CDC’, 15 December, Available at: <https://africacdc.org/covid-19/> [Accessed 15 December 2020].

[38] United Nations Children’s Fund (2020) ‘Cyclone Idai and Kenneth’, August 2019, Available at: <https://www.unicef.org/mozambique/en/cyclone-idai-and-kenneth> [Accessed 29 October 2020].

[39] African Union (2017a) ‘List of Countries which have Signed, Ratified/Acceded to the AU Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism of 2004’, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37291-sl-protocol_to_the_oau_convention_on_the_prevention_and_combating_of_terror.pdf> [Accessed 25 October 2020]. See also: African Union (2017b) ‘List of Countries which have Signed, Ratified/Acceded to the OAU Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism of 1999’, Available at: <https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37289-sl-oau_convention_on_the_prevention_and_combating_of_terrorism_1.pdf> [Accessed 25 October 2020].

[40] SADC (2020) op. cit.

[41] Government of South Africa (2020) ‘Briefing on the Security Situation in Cabo Delgado, Northern Mozambique, and its Impact on South Africa’s Foreign Policy Aspirations for a Secure and Peaceful SADC Region’. Presentation by Naledi Pandor, Minister of the Department of International Relations and Cooperation, Portfolio Committee on International Relations, 2 September, p. 12, Available at: <https://www.scribd.com/presentation/474604864/Presentation-to-PC-on-Cabo-Delgado-Final-02-09-2020#download&from_embed> [Accessed 25 October 2020].

[42] Ibid., p. 14.

[43] The Herald (2020) ‘Zim has No Troops in Mozambique: Minister’, 8 May, Available at: <https://www.herald.co.zw/zim-has-no-troops-in-mozambique-minister/> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

[44] Gerber, Jan (2020a) ‘Questions about SADF Deployment in Mozambique Unanswered’, News24, 9 July, Available at: <https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/isis-questions-about-sandf-deployment-in-mozambique-unanswered-20200709> [Accessed 25 October 2020].

[45] Fabricius, Peter (2020b) ‘South Africa Ready to Help Mozambique Fight Islamist Insurgency’. Daily Maverick, 3 September, Available at: <https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-09-03-south-africa-ready-to-help-mozambique-fight-islamist-insurgency/> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

[46] Machado, Zenaida (2020) ‘EU Counterinsurgency Aid to Mozambique Should Help Protect Rights’, Reliefweb, 14 October, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/eu-counterinsurgency-aid-mozambique-should-help-protect-rights> [Accessed 28 October 2020].

[47] Frey, Adrian (2020) ‘More Russians to Fight Terrorism in Cabo Delgado – Carta’, Club of Mozambique, 12 March, Available at: <https://clubofmozambique.com/news/more-russians-to-fight-terrorism-in-cabo-delgado-carta-155000/> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

[48] SADC (2001), op. cit., p. 12.

[49] DefenceWeb (2020) ‘South Africa is Ready to Help Mozambique with its Insurgency’, 3 September, Available at: <https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/south-africa-is-ready-to-help-mozambique-with-its-insurgency/> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

[50] Gerber, Jan (2020b) ‘ISIS Warns SA: Steer Clear of Mozambique Conflict’, News24, 7 July, Available at: <https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/isis-warns-sa-steer-clear-of-mozambique-conflict-20200707> [Accessed 30 October 2020].

[51] Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (2020b) ‘Cabo Ligado Weekly: 12–18 October 2020’, p. 1, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Cabo-Ligado-Weekly_-12-18-Oct.pdf> [Accessed 15 December 2020].

[52] AllAfrica (2019) ‘Mozambique: Nyusi will Talk to Insurgents – if They Show Their Faces’, 19 September, Available at: <https://allafrica.com/stories/201909160755.html> [Accessed 30 October 2020].