The problem of human-wildlife conflict (HWC) in Africa – meaning the interaction between humans and wildlife that results in negative effects for both humans and wildlife – poses risks to the preservation of livelihoods as well as wildlife conservation. HWC affects the food security of people, it decreases their physical and psychological well-being and increases their workload.1 In Botswana, for example, where the largest concentration of elephants on the continent can be found (estimated at 126 114 in October 2018),2 the significant number of elephants is not only putting pressure on the ecosystem, but has also led to increased HWC. The wildlife numbers pose a threat to human life, with official statistics indicating that between February 2018 and June 2019, 20 deaths by elephants and several injuries were recorded.3 Elephants encroach on communities, not only killing people but also destroying crops, thereby impoverishing the rural communities who rely on farming for their livelihood. Hidden costs in the form of diminished psychosocial well-being and disrupted social activities raise additional concerns.

On the other hand, HWC is ranked among the main threats to conservation in Africa.4 Given the previously mentioned negative effects for people, conservation efforts can be undermined by arising animosity and intolerance to wildlife. It can also increase illegal poaching and lead to the extinction of wildlife. Therefore, HWC poses a challenge to national governments, while the management of HWC can also generate political conflict between local people and government institutions. HWC is therefore a multifaceted problem.

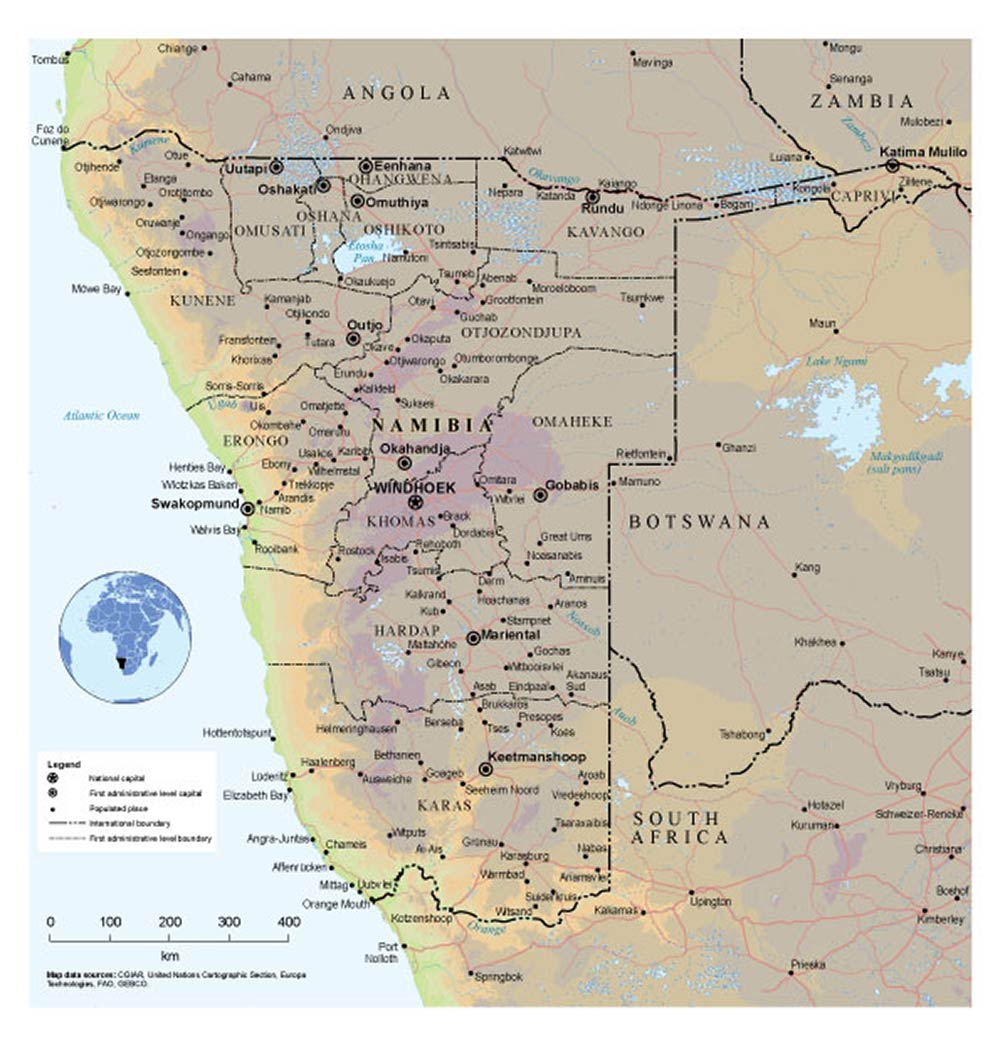

This article focuses specifically on HWC in Namibia, and draws attention to the manner in which the government approaches the problem of wildlife conservation and HWC. It also provides a brief overview of selected attitudes to wildlife conservation and HWC of the Ovahimba people in the Kunene region.

The incidents of HWC in Namibia are high, totalling 8 067 conflict incidents recorded in 71 of the country’s 83 registered conservancies during 2017.5 According to The State of Community Conservation in Namibia report,6 these figures may be an underestimation, given the fact that only 71 conservancies reported figures in 2017. Furthermore, HWC has increased, due to the growth in wildlife populations and the shifting patterns of movement of humans and wildlife in response to drought. Livestock attacks, in particular, have shown a substantial increase in 2017: there was an average of 106 incidences per conservancy, of which an average number of 91.1 were livestock attacks (up from an average number of 75.5 per conservancy in 2016) and 13.1 were incidents of crop damage, while the average number of human attacks per conservancy were only 0.2. Other conflicts related to wildlife and humans are damage to property (such as waterpoints and boreholes, fences, gates, kraals and houses), damage to vegetation and wildlife, and competition with livestock for forage.7

Wildlife conservation – and thus also HWC – in Namibia cannot be separated from the country’s community-based natural resource management programme (CBNRM) and its chosen model of conservancies.

Conservancies and Wildlife Conservation in Namibia

In 1996, the Namibian government created an inventive CBNRM that is concerned with the suitable management of natural resources – particularly, but not exclusively, wildlife on communal land. The Nature Conservation Amendment Act of 1996 was adopted, allowing rural communities the rights to manage and benefit from the use of wildlife and tourism. The CBNRM programme was intended to respond to several policy concerns in the country, ranging from the large drop in wildlife numbers on rural communal lands as a result of a combination of a civil war, drought and poor incentives to protect wildlife, to high poverty levels. Furthermore, white farmers had the right to manage wildlife found on their freehold land and benefit from the commercial use of this resource (enacted in the Nature Conservation Ordinance No. 4 of 1975). Therefore, white farmers held some property rights over wildlife, while black Namibians were denied these rights. Consequently, white commercial farmers had incentives to protect wildlife on their property, while for black people there was little incentive to protect wildlife on communal farms. Instead, they often cooperated with poachers to gain some benefit on their land. A change in the Ordinance provided black rural Namibians living on communal land with legal rights and responsibilities over their natural resources.8

Wildlife may now be utilised sustainably under conservation management in communal conservancy areas. CBNRM is therefore a policy to address conservation and rural economic development by giving local people incentives to search for profitable ways to manage wildlife and develop tourist-related activities. It operates through communal conservancies, each having clearly defined boundaries, a defined membership, a legally recognised constitution, an elected body of representatives for equitable distribution of benefits from resources to members, and a plan.9 The essential elements of good governance, set out by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) in its standard operating procedures (SOPs), are to be obeyed. The MET can degazette a conservancy that fails to comply with the SOPs.

There are currently 83 registered communal conservancies, covering 163 151 square kilometres (comprising 19.8% of Namibia), representing 52.9% of all communal land in Namibia and inhabited by an estimated 212 092 residents.10 The registered conservancies have achieved various levels of success. Conservancies earn income from tourism and hunting operations. In 2017, community conservation generated over N$132 million in returns for local communities, of which the benefits distributed by conservancies to members stand at an average of about 20% of conservancy income. These benefits are paid after costs – which include office expenses, vehicles and salaries (particularly to the game guards) – have been met.11 Besides the cash benefits, other benefits are in-kind, such as meat distribution and fringe benefits from tourism employment, such as staff housing. Other successes that have been achieved include remarkable wildlife recovery due to government and conservancy efforts – for example, a large free-roaming lion population outside of national parks and growth in the elephant population from 7 500 to 22 800 between 1995 and 2016.12 However, as noted previously, the increase in wildlife populations, together with the shifting patterns of movement of humans and wildlife in response to the three successive drought years since 2015 (the worst in 30 years), has resulted in a considerable increase in livestock attacks in 2017. In several places, people and wildlife compete for the same resources.

Namibia’s HWC Policy

One of the challenges to the CBNRM programme over the years has been HWC. Although HWC occurs throughout Namibia on communal as well as freehold land, the main problems occur on the communal land outside protected areas, where the most elephants and large predators are found and where people are the least able to bear the costs of losses and damages. In 2009, the MET implemented the National Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Policy. In 2018, a revised and updated policy was published to reflect changing circumstances (according to the report), a new thinking regarding HWC and the experience gained in managing the issues since the first policy. The government’s point of departure is that it is not possible to eradicate all HWC, but that the conflict has to be managed effectively so that it can be reduced to an acceptable level. The policy13 sets out a number of objectives, as well as 12 strategies to address the impact of HWC, including: land use planning and integrated measures to avoid HWC, appropriate technical solutions for mitigating HWC, removal of problem-causing animals, addressing the losses of affected persons, and HWC management schemes. The strategies can be categorised in terms of prevention (avoidance of such conflict and addressing its root causes), protection strategies (when the conflict has occurred or is about to occur) and, lastly, mitigation strategies (attempting to reduce the impact and lessen the problem).

The removal of problem-causing animals, for example, is allowed in exceptional cases where life and property are persistently threatened, or when the numbers of wild animals are so high that the conflict can no longer be tolerated by the resident people. This, however, can be done only with the authorisation of the minister in terms of strict requirements.

The Namibian government does not offer direct compensation to individual farmers or communities, due to the complexity of compensation schemes and their potential to be open to abuse. However, conservancies receive fixed payments through the Human Wildlife Conflict Self Reliance Scheme to compensate farmers for their losses. People in non-communal areas (similar to the 2009 policy) are also entitled to payments, but not people on private land. For every hectare destroyed by elephants, buffaloes and hippos, an amount of N$1 000 per hectare is paid out, while for livestock, N$300 is paid out for cattle, N$500 for a goat, N$700 for a sheep, N$800 for a horse, N$500 for a donkey and N$700 for a pig. Payments will be made only if certain requirements are met, such as reporting the incident within a day, keeping the animals in adequate livestock enclosures at night, and that the killing is verified by a ministry staff member or a community game guard (where such structures exist). Also, in incidents where a person is killed by a wild animal, N$10 000 is paid towards funeral cover. The stated amounts have increased by 50% from those set out in the 2009 report. Although the government acknowledges that the amounts do not cover the full value of the animal concerned, the purpose is to partially compensate the farmer for the loss. The revised policy has not made provision for property damaged by wildlife, as was the case in the 2009 policy. One of the government’s objectives is to establish an insurance scheme for human death and injury caused by wild animals, as well as a HWC livestock insurance scheme. Once in place, these insurance schemes will replace the Human Wildlife Conflict Self Reliance Scheme.

Attitudes of the Ovahimba in the Epupa Conservancy to Wildlife Conservation and HWC

The attitudes of local people towards wildlife is critical for communal nature conservation. On the other hand, HWC can have an impact on the attitudes of people towards wildlife, as wildlife can have a negative influence on people’s livelihoods.14

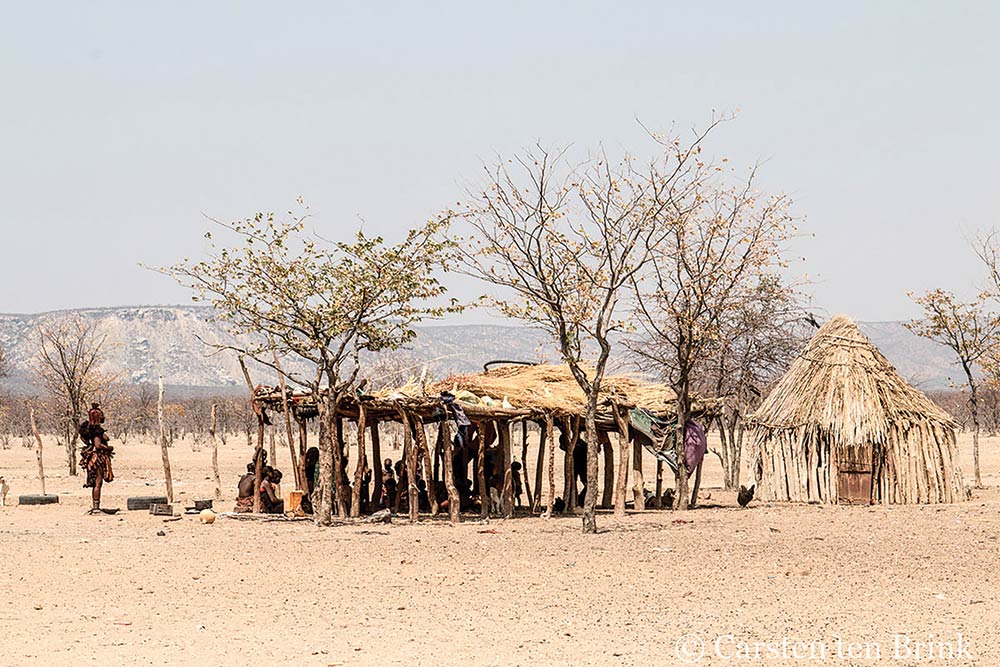

This research focused on the Epupa conservancy (it includes the Epupa Falls), which is located in the north-west of Namibia and is one of the most recently registered conservancies (gazetted in 2012), with approximately 3 518 permanent inhabitants. The semi-nomadic Ovahimba people are the native occupants of the conservancy. Pastoralism (goats, cattle and sheep) is the main form of subsistence.

Three focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in May 2019. One FGD consisted of 10 women and was conducted in the vicinity of the Epupa Falls. A snowball sampling technique was used to recruit the women, who came from seven different villages. The second female FGD was conducted approximately 60 kilometres north-west of the Epupa Falls. These women, from five different villages, were busy building a kraal with huts to display their culture to tourists. A male FGD, which consisted of 17 men from eight different villages, was conducted in the same area. The men were gathered for a traditional ceremony. A female interpreter was used for the female groups, while a male interpreter accompanied a male interviewer. A number of informal discussions were also held with individuals in the conservancy.

The focus of the research was not specifically on HWC, but on the broader topic of wildlife conservation, poaching and the role of the conservancy. Given the fact that people’s attitudes to wildlife can be influenced by the negative effects on livelihoods of such conflict, the issue of HWC was also raised.

The first aspect raised with the focus groups was to establish their attitudes towards the conservation of wildlife (or killing of wild animals). Respondents made it clear that before the conservancy, it was acceptable to kill wild animals. However, “nowadays it is not good to kill wild animals.” Various reasons were provided, such as:

- “wild animals are our own”;

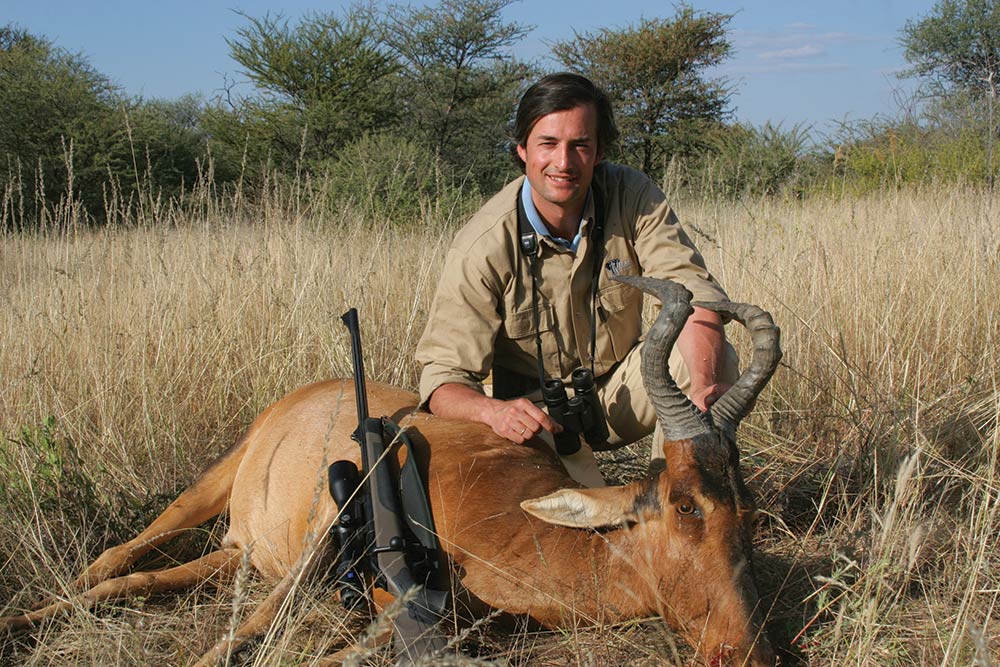

- “the community benefits when hunters with permits come and hunt – so wild animals should not be killed off”;

- “wild animals should be protected because that will bring development to the community (in this regard, trophy hunters are great because they bring in money)”;

- “the conservancy is our area and outsiders cannot come and destroy this”; and

- “wild animals are the responsibility of the community – it is important to keep wild animals for the future generation”.

If people are caught killing wildlife, they will go to jail. Respondents were also adamant that they would report people who kill wild animals such as kudu.

On the question of whether wildlife have killed some of their animals, a number of respondents indicated that their animals have been killed on several occasions. The most troublesome animals are jackals, hyenas, leopards, cheetahs and crocodiles. To members of the focus group in the Epupa Falls area (Kunene River), crocodiles pose the biggest problem to both humans and animals, and some women had no problem with the idea of killing/shooting the crocodiles, which has been done on the Angolan side of the river. The women who live more inland stated that their goats were killed by jackals and hyenas. The women stay in the villages with the goats while the men go with the cattle into the mountains for better grazing, where they are attacked by cheetahs and leopards. They have had no incidents of crop damage, since crops such as maize, pumpkin and watermelons are no longer planted because of the persistent drought. From the discussions, it became evident that retaliation killing of troublesome animals (except crocodiles) is not an option to those who have lost livestock. In the words of one woman: “If jackals kill our livestock – how can we kill it if it is part of our wildlife – hunters would like to kill so protect them.”

The greatest concerns, however, relate to the issue of compensation for livestock death by wild animals. In this regard, two problems were mentioned. First, the compensation is inadequate. The amount paid out is below the replacement value of the animal. As one respondent remarked: “If 10 goats are killed, we will only get paid the worth of two goats.” The second problem relates to the payment process. In the words of respondents:

- “we do not get paid”;

- “payments are not processed”;

- “only some people get paid”; and

- “the conservancy/government takes time to pay”.

From the informal discussions with community members (including some of the focus group respondents), it seems that reimbursements or payments to livestock owners are not made because many do not meet the policy compensation requirements. For example, livestock are mostly left unattended during the day and are also not in enclosures at night, as required by the HWC policy. Furthermore, due to distances and an immediate lack of transport, as well as no credit on phones or bad reception, the killing of their animal is not reported within the required 24-hour period. On the other hand, community members confirmed that they are also aware of the fact that compensation (from the conservancy) for killed livestock takes a long time to be processed, or that these “payments” are not made at all. Given the requirements in terms of reporting and the problem with reimbursements, losses are increasingly not being reported. This situation has an impact on official figures on HWC in the conservancy.

Given the fact that the conservancy is the model for the CBNRM programme on wildlife conservation and development, it was also important to establish the attitudes of respondents to the role of the conservancy. Some of the respondents did not know much about the conservancy, while the majority had mixed views. Positive aspects about the conservancy that were raised were:

- “the conservancy gave us the idea to build huts to show our culture to tourists and preserve wildlife”;

- “they brought water close to us”;

- “before the conservancy we cut trees – now we must ask for permission – it is good because trees have been damaged”;

- “the conservancy is a good thing – they made four boreholes”;

- “they provided waterpoints”;

- “we only see good from the conservancy”;

- “they [the conservancy] introduced rotation of grass for animals so that other parts grow – before the drought – now grass does not grow”; and

- “conservancy protects wildlife – we trust them”.

Respondents also mentioned the fact that they have a conservancy meeting the first week of every month, where they talk about wild animals. Negative points against the conservancy were also raised, such as the lack of payment for killed livestock by wild animals, and that the conservancy makes money from the lodges, tourism and hunting, but the local people do not get any of this.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that Epupa is one of the most recently established conservancies, it was evident from all the FGDs that the message of the value of conservation – and particularly wildlife conservation – has spread in the community. Before the establishment of the conservancy, respondents acknowledged that wild animals were not protected. Furthermore, the benefits of wildlife, such as hunting and tourism, have made respondents more appreciative of the value of wildlife.

The positive attitude towards wild animals also seems to have an effect on their attitudes to HWC. The immediate reaction of respondents to questions on these attacks was not that of killing the animal (except for crocodiles), but rather the fact that they are not adequately compensated for their losses. Not only were the amounts paid out far below the value of the animal killed but, in many instances, they have reported their losses but have had no payments from the conservancy. The reasons for the failure of payments are not quite clear – whether it can be attributed to failing to meet the requirements set out in the government’s HWC or incompetence on the side of the conservancy/government. The fact that the men have to travel to different areas with their cattle as a result of the drought does create problems of securing animals in enclosures at night, while it is also often problematic to report incidents within the required 24 hours. This could possibly change the attitudes of the community to HWC and back to the retaliatory killings of troublesome animals, if this issue is not addressed by the conservancy and the government.

The severe drought in the area poses a serious problem for the community. Not only are they losing livestock because of the drought due to a lack of grazing, but the availability of wildlife (for permit hunting) is also affected. This could also lead to an increase in incidences of HWC. If the drought continues, the community may, as a last resort, be compelled to illegally hunt kudu and other wild animals for food. For the protection of wildlife and the potential impact of the drought on HWC, the conservancy needs to engage with the community on ways in which the effects of the drought can be mitigated.

Endnotes

- Kahler, Jessica S. and Gore, Meredith L. (2015) Local Perceptions of Risk Associated with Poaching of Wildlife Implicated in Human-wildlife Conflicts in Namibia. Biological Conservation, 189, p. 49.

- Chase, Michael; Schlossberg, Scott; Sutcliffe, Robert and Seonyatseng, Elford (2018) ‘Dry Season Aerial Survey of Elephants and Wildlife in Northern Botswana (July-October). Survey Conducted Jointly by Elephants Without Borders and Department of Wildlife and National Parks (Botswana)’, p. 19, Available at: <http://elephantswithoutborders.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2018-Botswana-report-final-version-compressed-upload.pdf.>

- Dube, Mthokozisi (2019) Elephant Hunting Ban is Lifted. The Star, 18 July, p. 24.

- Muruthi, Philip (2005) Human Wildlife Conflict: Lessons Learned from AWF’s African Heartlands. AWF Working Papers, July, p. 1.

- Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET)/Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organizations (NACSO) (2018) The State of Community Conservation in Namibia: Annual Report 2017. Windhoek: MET/NACSO, p. 45.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Boudreaux, Karol and Nelson, Fred (2011) Community Conservation in Namibia: Empowering the Poor with Property Rights. Economic Affairs, 31 (2), pp. 17-18.

- Mufune, Pempelani (2015) Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) and Sustainable Development in Namibia. Journal of Land and Rural Studies, 3 (1), p. 123.

- MET/NACSO (2018) op. cit., p. 28.

- Ibid, p. 13.

- Ibid.

- MET (2018) Revised National Policy on Human Wildlife Conflict Management 2018-2027. Windhoek: MET, pp. 10-25.

- Störmer, Nuria; Weaver, L. Chris; Stuart-Hill, Greg; Diggle, Richard W. and Naidoo, Robin (2019) Investigating the Effects of Community-based Conservation on Attitudes Towards Wildlife in Namibia. Biological Conservation, 233, pp. 193-194.