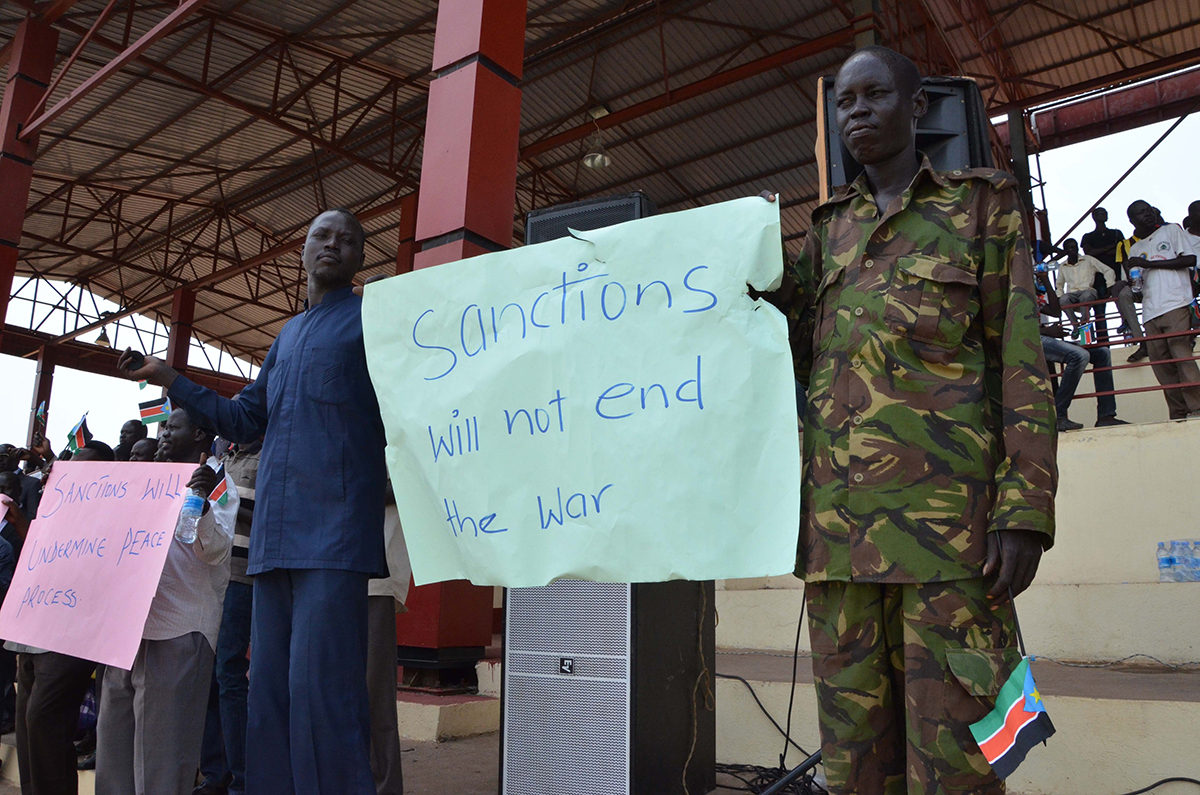

The misguided application of targeted sanctions in South Sudan will not support peace; rather, they have the potential to foster conflict.1 Nor are targeted sanctions the appropriate forum to further justice. The following consideration of the use of targeted sanctions in the case of South Sudan’s current internal conflict (2013-2015) and peace process concludes that rather than support peace, as the sanctions presented by the United States (US), European Union (EU), Canada and, most recently, the United Nations (UN) Security Council purport, they are at best benign, and at worst, present a threat to sustainable peace.

On 8 September 2015, US, British and French representatives at the UN Security Council circulated a proposal, under Resolution 2206, to add targeted sanctions on a further two South Sudanese leaders they claim are obstacles to peace. Even though Russian and Angolan representatives voiced objection, forcing the deferral of the proposal,2 the choice to propose further sanctions – only weeks after a peace agreement between the warring parties was resolved – raises questions regarding these sanctions specifically, and the usefulness of targeted sanctions in supporting peace, more generally.

South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir Mayardit and opposition leader Riek Machar (formerly vice president, before his rebellion) agreed to peace in August 2015. There has been a struggle to maintain this agreement; indeed, many suggest there is little peace to keep.3 The most recent report by the official body monitoring the process has reported more than 50 violations of the ceasefire in the last 19 months – 29 violations by the rebel opposition forces and no less than 24 attributed to government forces.4

In the context of a faltering peace, the approach by those advocating sanctions is to single out specific individuals whom they conclude are responsible for continuing conflict and undermining the peace. These sanctions are, in one way or another, meant to remove these individuals from the equation and to deter others from similar recalcitrance – so goes the narrative. The most recent sanctions proposal targets the South Sudanese military’s chief of staff, General Paul Malong Awan, along with opposition commander Major General Johnson Olony. The newly proposed sanctions are meant to pressure these individuals to prevent violations of the peace. Instead, like earlier sanctions, they are likely to exacerbate the politics poised to undermine peace, and can even be directly connected to some of the violations of the agreement.

Sanctioned Leaders are Critical for Peace

The first and most obvious flaw in the choice to add further sanctions is the fact that those being sanctioned will undoubtedly prove critical in the process of implementing the peace agreement, especially security provisions and wider security sector development. To alienate them now, when neither party to the peace is requesting such action, is highly questionable.

Just as those being targeted were important players in the conduct of the conflict, they too will prove critical in securing the implementation of peace. If they and their corresponding support groups are alienated by such sanctions, the result is that these figures could regroup and force continued threat and conflict.

We have already seen several top commanders of the opposition forces of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition (SPLM-IO) rebelling from their own group after they were sanctioned by the US, EU and Canada. The leadership of the opposition group used the discrediting of the sanctions to sideline powerful commanders. The resulting politics saw these powerful commanders move to continue their struggle with their own rebel group. The most prominent example is General Peter Gadet Yaka, who has since sought support from the Sudanese government in Khartoum, and has launched various campaigns to scuttle the current power-sharing agreement.5

A former state governor and revered leader of the civil war that led to South Sudan’s independence, General Paul Malong Awan’s leadership of a key South Sudanese community, a wide patronage network and his importance in the security sector, means he is an important figure in securing peace. His centrality in the conduct of the counter-rebellion effort, in particular, corresponds to his centrality in securing and implementing any peace agreement.

Malong is one of many military leaders – including those already sanctioned – on both sides of the conflict, who will prove important to the success of the implementation of the current agreement. In particular, the extensive security provisions will require a lot of military leaders, both in terms of compromise and in technical competence. The senior and more experienced leaders of both sides will thus have to work together to make the peace agreement function.

Most of the top leaders targeted by sanctions have a history of leadership dating to the previous civil war in Sudan, and many – such as Malong – have even longer histories of military leadership, going back to resistance to colonialism. Their exploits during war mean that such leaders are revered and respected – not only in the military, but in wider society. Most of the older leaders are seen by their respective communities as heroes of the liberation struggle, and for many, like Malong – whose home region was one of the more remote but main frontlines resisting northern Sudanese efforts to Arabize and oppress Southerners – are seen as defenders of their people.

Dismissing this history and influence runs counter to the functioning of society in South Sudan. To ignore this reality and move to impose narrow, targeted sanctions suggests a lack of appreciation of political and social dynamics in South Sudan, which are central if anyone is interested in building or even supporting peace. This is not to reject the idea of justice and accountability, however. Nor is it the proposition that security must come before justice, as some have proposed.6 Rather, the argument here is that measures to support peace must be designed with the utmost care, in a manner appropriate for the particular context. Targeted sanctions as they stand are far from reflective of South Sudan’s cultural, social, political and historical context.

Deterrence and Individuals

Those proposing sanctions claim that, by pressuring individual leaders in this way, the powerful will be compelled to maintain peace. They also argue that sanctioning a few major figures will serve as deterrents – other players, fearing similar moves might be made against them, will act accordingly to avoid sanction. Instead, these sanctions risk further polarising the political situation between groups opposing each other, and within the leaderships of both government and opposition forces.

After the last round of sanctions, with leaders of all parties still deeply suspicious of the tenuous peace deal, forces loyal to sanctioned commander Gadet broke with the opposition group. Believing they would lose out, they opposed any peace deal. Indeed, once sanctions were imposed, rebel SPLM-IO leader Machar moved to dismiss Gadet and other commanders. Presumably, this was because the international community had blacklisted these commanders, so continued association would have made courting international political and material support more difficult for Machar and the SPLM-IO. At the same time, Gadet declared his own rebellion against the SPLM-IO of Machar and the government, and has since been launching attacks. Thus, in part, the sanctions contributed to cleavages within the opposition forces. Instead of compelling Gadet to become a partner in peace, he is now a spoiler.

The idea of deterrence not only ignores the lessons of history, as noted above, but also ignores the realities of South Sudanese society. South Sudan is a proud, martial society where resistance has become a way of life, due to the long liberation wars dating back to the colonial period. Using threat and sanction to make an example of some to threaten and deter others from action has little foundation in society. Not to mention the fact that this method, designed to work in an individualist society, is unlikely to function as expected when applied to South Sudan’s communal society.

Added to the problems identified above regarding how the sanctions will function to deter, most of those sanctioned have little or no international financial holdings and travel infrequently. Thus, the current regime of sanctions has had little real impact on those already sanctioned, all of whom still hold their positions. For a deterrent to function, an appreciable negative impact needs to be felt, so that the perceived cost of continuing the actions associated with the sanction become too high for others and they are coerced into changed behaviour.

The following is a list of those sanctioned to date, and their current status since being sanctioned:7

| Rebel/Opposition SPLM-IO commander | Status since initial targeted sanctioning |

| Major General James Koang Chol | Remains an active commander |

| Major General Simon Gatwich | Remains an active commander |

| General Peter Gadet Yaka | Leading his own rebellion after defecting from the SPLM-IO |

| Government/SPLA officers | Status since initial targeted sanctioning |

| Lieutenant General Gabriel Jok Riak | Remains the top field commander of the SPLA, sector one commander |

| Major General Marial Chanoung Yol | Continues to be a senior officer and head of the Presidential Guard |

| Major General Santino Deng Wol | Remains an active commander in the SPLA |

The evidence, thus, is in the result – all those sanctioned continue to be important military leaders, conducting operations, since the sanctions were imposed by the US, EU, Canada and UN. Nor have the sanctions curtailed the willingness of other leaders to conduct aggressive military operations.

The targeted sanctions already imposed have even made several leaders more popular and influential. The sanctions create incentives for more extreme action, because anyone seen flaunting this is viewed by many in South Sudan as resisting outside meddling, even resisting renewed colonialism or neo-imperialism by the West. Acting in direct opposition to the sanctions, and flaunting this in language and action, thus becomes an act of resistance. Resistance is laudable in South Sudan, and thus the sanctions and the rejection of them by leaders is perceived to be contrary to the way those designing them may have believed would be the case.

It is widely understood that political figures on both sides have encouraged the conflict to escalate rapidly into one with an ethnic narrative and frame. This problem has been pointed out clearly by observers, such as the International Crisis Group.8 However, this most recent round of proposed sanctions again focuses exclusively on military leaders. Despite many observers and those involved recognising that many military figures have been more inclined to negotiate and work with mediators to resolve the current conflict, the international community continues to target military figures rather than politicians.

Thus, the sanctions have compelled an increased determination by several of those sanctioned to press their campaigns forward and prove their power and influence in military terms, so that they cannot be ignored by the coming power-sharing government and future political dispensation. The result is pushing political and military figures to more extreme positions than they may otherwise have taken, with little practical pressure in financial or other terms. Clearly, this is the opposite of the intended result of sanctions.

Divide and Rule Rather than Support for Peace

A deeper consideration of the use of sanctions in South Sudan suggests that it is impacting internal political dynamics by dividing key leaders and groups. Dividing leaders in government, in particular, but also among the opposition, resembles the efforts of divide and rule employed by foreign governments to control states in the colonial period and during the cold war. The purported justification and purpose of the sanctions is to secure peace. Internal division, competition and confrontation are certainly not in line with the goals set out for the sanctions regime.

Targeted sanctions have the potential for – and are currently resulting in – increasing internal competition. Both opportunists and those looking to support the state are making political manoeuvers in response to the way the sanctions have framed individuals as beyond the bounds of acceptance. It follows that any leader sanctioned needs to be sidelined, and this makes space for new leaders to step in. While in theory this may seem a strong strategy, if leadership for the large part has been determined to be recalcitrant and uncooperative with the international community, it is more likely to have the disastrous consequence of creating further divisions, and further cleavages to be exploited and leveraged into justifications for violence and political machinations.

Paul Malong Awan, at the airport in Juba, upon arriving after attending peace talks in Ethiopia (6 March 2015).

Gallo Images/Reuters/Jok Solomun

While some in the press and diplomatic circles have suggested that sanctions and other pressure from Western states helped push the South Sudanese leadership to accept the most recent peace terms, in actual fact, they made it increasingly difficult for the president or others in the government to sell peace to their core constituencies. The various communities in South Sudan tend to interpret the situation as a zero-sum game, in which compromise is tantamount to loss.

Targeted sanctions are an attempt to use coercion to support peace. Perceived as part of a wider agenda to impose a political outcome on South Sudan, the sanctions reinforce the belief held by many that the current conflict, peace process and other actions of the international community are threats to the survival of their community; at least, a part of the threats to their community laid bare by the current conflict. This perceived threat is likely to be met with strong resistance, which frighteningly translates into justifications for violent defensive action, with many seeing their communities facing an extreme emergency.9 The international community should be striving to work against this zero-sum view of conflict and towards engagement around the idea that a compromise accord can have a positive sum outcome for a future South Sudanese nation, with all communities playing important and included roles.

Furthermore, sanctions against the top leaders impact the internal brokering for the next set of political postings. Much of South Sudan’s politics focuses on who gets which post in government and the bureaucracy. The sanctions will affect the internal power dynamics in the government and ruling political party. This certainly runs counter to stability and sustainable peace theories. Worse, it borders on negative meddling. Again, to ignore the reality of the system and society in South Sudan, regardless of one’s judgement of it, is a barrier to designing effective interventions in support of peace.

A final way that targeted sanctions can have a destabilising effect on the political dynamics in South Sudan is the creation and/or cementing of potential spoilers to the peace. The sanctioning of the sometime opposition/sometime government commander Olony is one such example of how the sanctions could contribute to the spoiler effect. To date, Olony has been willing to resolve deals with the government, but has also shown himself willing to rebel from the government and from the SPLM-IO when placed in positions he feels are disadvantageous, or if he sees alternative opportunity. The rewards of rebellion are thus higher than remaining loyal – at least by his calculations. If placed in a situation that jeopardises his access to financial or political concessions in the power-sharing agreement or future government, Olony, like many others, is not daunted to use force to assert control of certain geographic spaces and, through this, effectively deny the monopoly of government violence. The past has proven that this strategy works, and there is little reason why targeted sanctions applied in the current context would change that.

Further, the placing of sanctions on a leader like Olony is likely to place such leaders in a situation where there is little advantage to maintaining peace, as they are effectively ostracised for future political legitimacy in the eyes of international actors and the terms of the new government arrangements under the peace agreement. The dynamic result is that there are incentives for Olony to assert his and his armed group’s control of space to force their inclusion.

There are many people in situations similar to Olony. Gadet has already proven that when placed in an ostracised political position by sanctions, the incentives to move to spoil the current peace are higher than the costs. As noted previously, since being sanctioned, he has coalesced his armed group and supporters on the ground, along with accessing resources and support from the government in Khartoum. The Sudanese government in Khartoum seems content with a destabilised South Sudan as part of its own internal security effort, since South Sudan is believed to be a supporter of several rebel opposition groups in Sudan, particularly the SPLM-North in the Blue Nile and Nuba Mountains.10

Sanctioning Communities not Individuals

Ironically, the opposite of the logic being applied by those advocating sanctions targeted on individuals is true – sanctions of individuals in South Sudan have consequences akin to blanket/general sanctions. This problem with targeted sanctions functions in two ways: (1) undermining the distribution of income via a patronage network, and (2) fostering intercommunal competition and conflict.

In South Sudan, there are very wide patronage networks that function around the elites of each community, extracting wealth from the state and other sources and then dispersing it through their network. The essential point here is that by cutting off the ability of individual leaders to engage in wealth creation and dispersion, the community is hurt. And since most leaders are likely to impose austerity in the system from the wide end of the pyramid first – thus protecting their personal and inner circle from loss – targeted sanctions can have the result of hurting large groups of civilians not directly involved in or responsible for conflict. Despite the dysfunction of this patronage system in broader development or governance, it is the system that currently exists, and should only peacefully be changed over time on the terms of the South Sudanese themselves.

A further and potentially deeper problem related to social structure is the fact that just as people vote and act politically in community groups, the targeting of a community’s leader translates into targeting the entire community. Thus, for example, to sanction Malong is to target his community in Northern Bahr el Ghazal. Sanctions imposed by purportedly impartial international actors can then be leveraged by rival communities to brand the community of a sanctioned leader as a problem, and can correspondingly give justification and support to intercommunal competition. A sanctioned community thus could become the target of a group that now sees the sanctioned community as weak and possessing material resources which could be taken with justification, harkening to the international sanctions.

What’s more, the selection of certain individuals to sanction – and, in so doing, certain communities – provides the motive and justification for revenge by other communities, which correspondingly blame associated communities for acts the sanctioned leaders are said to be responsible for. This dynamic is the most dangerous, and the most likely, in the heated and cleaved ethnic situation in South Sudan.

The Wrong Forum for Justice

A final major problem worth noting, with respect to the use of targeted sanctions in South Sudan, is how they are being used as a punitive action, but are not being carried out by a judicial actor. Further, South Sudan is a society that has long held a restorative principle of justice, rather than a punitive one focused on individual perpetrators.

All the targeted sanctions – those applied unilaterally by the US, EU and Canada in preceding years, and those recently applied by the UN – are meant to support peace, not punish wrongdoing. It is clear from comments by US and other state officials that these sanctions are seen as a means to punish war crimes, rather than compel or support peace.

Sanctions are meant to pressure to secure peace, not as a stand-in for a legitimate judicial or court process. They further threaten any future judicial effort to bring those responsible for war crimes or other violations to justice, as the sanctions and rhetoric associated with them are likely to prejudice any future case. Thus, the use of sanctions to punish has no basis in a court or judicial process. And it is of concern why the international community is resorting to this kind of mechanism to pass summary judgement of guilt, without due process.

With the effort to create a hybrid court in South Sudan, to address any crimes committed during the war, included in the peace yet to be established, it is presumptuous and dangerous for the UN Security Council or others to pass judgement in a political forum rather than a judicial one. The cases for sanctions cannot be challenged by those accused nor by anyone else for accuracy. This presents a major problem in terms of assessing the balance of the potential value of the sanctions and the potential dangers. Not only are the sanctions not likely to support peace, they are likely to compel conflict. Added to this, they are likely to prejudice and undermine efforts at justice in South Sudan. It is clear that justice is essential to sustainable, positive peace in South Sudan.

While many focus on the headline-grabbing sanctions, the real work of peacebuilding – through a national reconciliation process and an active nation-building constitutional process – has been left aside. Until focus is placed on these processes, justice will continue to prove elusive in South Sudan.

Political Marketplace and More Harm than Good?

There is clearly a political marketplace in South Sudan,11 which has been the only means through which any stability has reliably been achieved. Upon taking office, Kiir used the large oil wealth and major financial support to purchase the loyalty of major factions that might have opposed him – often referred to as “Kiir’s Big Tent”.12 As those resources dried up, with oil prices plummeting and Western willingness to bankroll this effort disappearing, defections and rebellions increased. Political moves by more centrally placed figures, compounded by a heavy-handed response by government, sent the infant country into a disastrous spiral of political violence. At least in the short term, the use of the political marketplace to purchase loyalty for stability has had a much better track record. With the political marketplace in South Sudan nearly bankrupt, targeted sanctions only ostracise factions and create more desperation in the political marketplace.

Instead of working on new and more creative ways to secure peace – such as using the inclusion of the wider public to convince leaders of the merits of power-sharing and cooperation – the international community, by using sanctions, further exacerbates the dynamics of threat and force. With growing financial restraints due to oil prices and other issues, the threat of sanctions undermines any opportunity to support stability through the South Sudanese political marketplace. While problematic in many respects, South Sudan’s collective society, with tribe and identity deeply connected to patrons, can only evolve slowly over time. To try and change it using threats is, at best, reflective of the ignorance of the social structures that must be taken into account to achieve peace.

So what are the goals of these targeted sanctions? The documents proposing the most recent round of sanctions suggest they are meant to “impose consequences for breaches of the ceasefire agreement”.13 South Sudan has already suffered the consequence of the war; even the people being targeted are not ignorant of those consequences. UN Resolution 2206 (2015) concerning South Sudan talks about supporting and building peace, and given the myriad problems discussed herein, it is difficult to see how the current targeted sanctions serve these goals of peace, stability and security. Rather, the sanctions seem to reflect more of an act for the consumption of domestic audiences in the West, leaders desiring to look as though they are doing something – anything – with little real cost for their action.

To genuinely support peace, we need intensive diplomatic work and strong humanitarian efforts, and innovative models of mediation and negotiation – not further bravado and aggressive posturing, no matter how well such bravado plays in Western states during an election cycle. Western states have backed away from the kind of heavy lifting required to support peace in South Sudan – targeted sanctions are a poor replacement for creative diplomacy and mediation efforts. South Sudan would have been better served by international actors supporting the effort to build a more inclusive peace process, but that was abandoned at the first signs of cost and difficulty. Key actors capable of crossing the conflict’s dividing lines, such as churches, were not effectively or sufficiently included in the process, because international governmental actors wanted the credit for being the peacemakers.

If its proposed goal of furthering peace is sincere, the international community must learn from recent experience, and urgently find a more effective course of action. The simplistic need to be seen as ‘acting’, with little cost, will be of no help to those suffering, and will likely do more harm than good.

Endnotes

- A brief early version of this argument is contained in a blog post/opinion piece by Matthew LeRiche for the Centre for Security Governance, where the author is a Senior Fellow. See LeRiche, Matthew (2015) ‘Targeted UN Sanctions in South Sudan a Threat to Peace’, Available at: <http://www.ssrresourcecentre.org/2015/10/29/targeted-un-sanctions-in-south-sudan-a-threat-to-peace/>.

- BBC (2015) ‘South Sudan Sanctions Blocked by Russia and Angola’, 16 September, Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-34267405>.

- Blair, David (2015) ‘British Troops in South Sudan will have No Peace to Keep’, The Telegraph, Available at: <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/south-sudan/11926263/British-troops-in-South-Sudan-will-have-no-peace-to-keep.html>.

- Office of the IGAD Special Envoys for South Sudan (2015) ‘The IGAD Monitoring and Verification Mechanism’, Available at: <http://southsudan.igad.int/index.php/2014-08-07-10-16-26>.

- Reeves, Eric (2015) ‘Khartoum’s Arming of Renegade Rebel Elements’ Available at: <http://sudanreeves.org/2015/06/26/khartoums-arming-of-renegade-rebel-elements-a-serious-threat-to-peace-in-south-sudan-26-june-2015/>.

- LeRiche, Matthew (2014) ‘In South Sudan Courts and Justice are Essential for Peace: A Reply to Mbeki and Mamdani,’ African Arguments, Available at: <http://africanarguments.org/2014/02/19/in-south-sudan-courts-and-justice-are-essential-for-peace-a-reply-to-mbeki-and-mamdani-by-matthew-leriche/>

- For more detail, see the actual sanctions list, Available at: <http://www.un.org/sc/committees/2206/2206.htm>.

- ICG (2015) ‘No Sanctions without a Strategy’, 29 June, Available at: <http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/media-releases/2015/africa/south-sudan-no-sanctions-without-a-strategy.aspx>.

- Sometimes referred to as ‘Supreme Emergency’, the principle in international law holds that when faced with a clear existential threat to the community or nation, governments are justified to take measures that would normally be considered beyond acceptable conduct. This particularly relates to the use of violence and the revocation of rights.

- The leaders and much of the body of supporters and fighters in the SPLM-North in Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile, fighting the government in Khartoum, are the remnants of the SPLM/A, who were effectively left behind in Sudan as South Sudan gained independence as part of the culmination of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that ended the Sudan Civil War between the SPLM/A and the government of Sudan. Deep personal ties still link many in South Sudan and the groups in Blue Nile and Nuba Mountains.

- De Waal, Alex (2014) ‘Legitimacy and Peace Processes: From Coercion to Consent,’ Accord, 25, Available at: <http://www.c-r.org/accord/legitimacy-and-peace-processes/violence-and-peacemaking-political-marketplace>, and De Waal, Alex (2015) ‘Two Rationales for Imposing Sanctions on South Sudan’, African Arguments, Available at: <http://africanarguments.org/2015/08/24/two-rationales-for-imposing-sanctions-on-south-sudan/>.

- LeRiche, Matthew and Arnold, Matt (2012) South Sudan: From Revolution to Independence. New York: Oxford Press, pp. 160, 199.

- The UN Security Council Committee established pursuant to Resolution 2206 (2015) concerning South Sudan. ‘Note By the Chair’, Communication dated 5 September 2015 from the United States Mission to the United Nations addressed to the Chair of the Committee Including Communication of US, UK and France proposed listings in pursuance of Resolution 2206 (2015). UN Document, S/AC.57/2015/NOTE.30, 8 September 2015.