Introduction

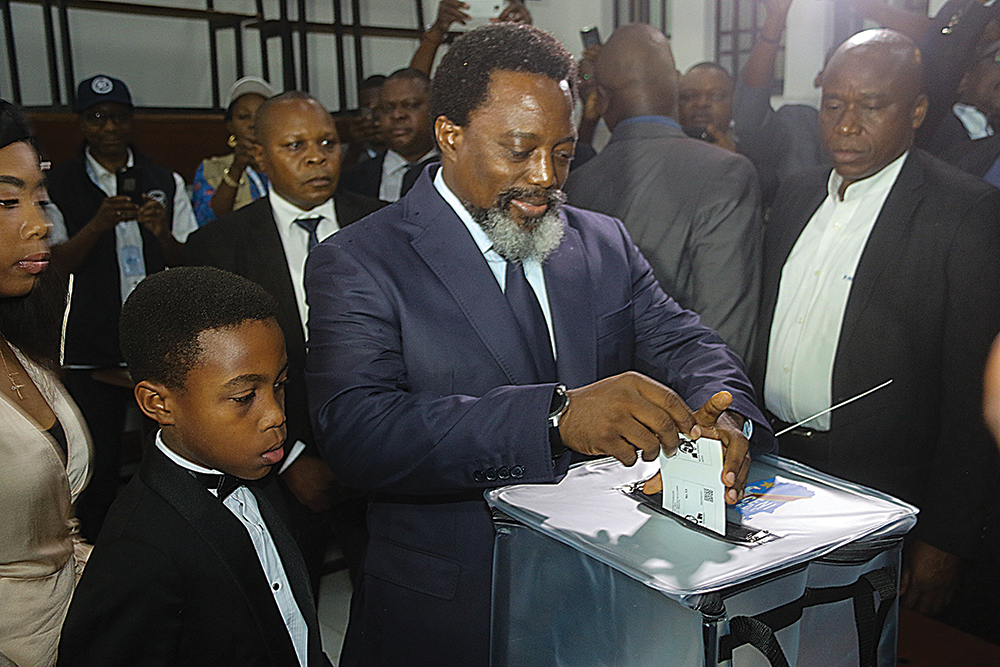

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has been home to the one of the oldest peacekeeping missions in the world – the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) – due to many periods of instability. Since independence in 1960, the country has been embroiled in conflict. Joseph Kabila succeeded his late father, Laurent Kabila, as president, following the latter’s assassination in 2001. He ruled the country for almost 17 years, and controversially won two elections, in 2006 and 2011. His tenure expired in November 2016, necessitating presidential and legislative elections. However, in September 2016, the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI) announced the postponement of elections, citing reasons of violence in parts of the country, as well as logistical and financial constraints. CENI also petitioned the Constitutional Court and obtained authorisation to postpone elections to compile a fresh voter register. These developments were met with widespread anger and protests over what some saw as Kabila’s refusal to relinquish power at the end of his second constitutionally mandated term.

In the face of a legitimacy crisis and mounting domestic and external pressures from western powers, the African Union (AU), the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), combined presidential, legislative and provincial elections were held on 30 December 2018. The initial announcement to the elections was met with some reservations. Nonetheless, the elections took place. Contrary to widely held views of machinations by the incumbent government to cling to power, long-time opposition leader, Félix Tshisekedi, emerged as the new president of the DRC, having secured over 7 million votes, representing 38.57% of the total votes cast. The runner-up – another opposition candidate, Martin Fayulu, leader of the Lamuka coalition – garnered about 6.3 million votes (34.38%). The ruling coalition’s candidate, Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary, came in third with over 4.3 million votes, representing 23.84% of votes cast.1 The voter turnout was 47.6%. However, Fayulu, who led the pre-election polls, filed a fraud complaint with the country’s highest court, calling for a recount of the official results. The court upheld the results. The DRC’s Catholic Church also intimated that the results gathered by its 40 000-strong monitoring team pointed to a different outcome than announced by the electoral commission.2 The disputed elections have larger consequences for the post-Kabila government.

This article discusses the issues surrounding the elections and implications for stability in the post-election environment. The first section discusses the contentious issues that characterised the pre-election phase. This is followed by an analysis of developments in the post-election environment and the overall implications for stability.

Contentious Pre-election Issues

Electoral preparations did not include some of the important elements of the Saint Sylvester Agreement, signed by the government and its opponents on 31 December 2016. This agreement was brokered by the influential Catholic bishops of the National Episcopal Conference of the Congo (CENCO), following the heavy security clampdown on protesters calling for Kabila to step down.3 The agreement set out a power-sharing roadmap for the transition period until elections by 31 December 2018. The agreement forbade Kabila from attempting a third presidential term and precluded constitutional amendments during the transition period. It also outlined certain measures meant to ease political tensions, including the release of political prisoners.4

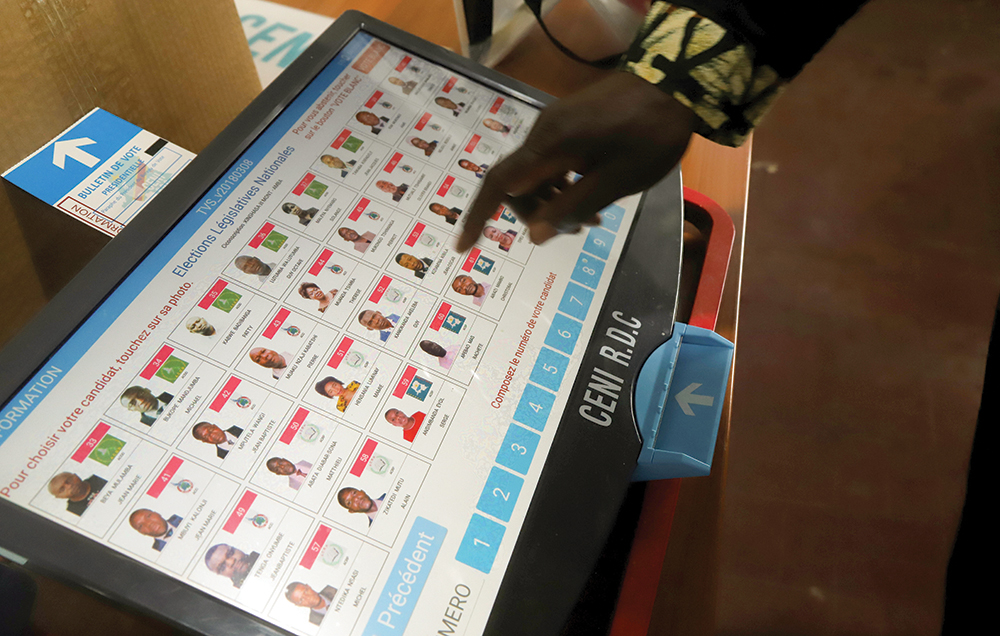

Following the announcement of the electoral calendar, preparations for the election started. These included new electoral legislation, voter registration, introduction of new voting technology, and dialogues between the CENI and opposition parties. Kabila approved a new electoral law on 24 December 2017. This law included provisions that sought to reduce the huge number of candidates, as was experienced in previous elections in 2006 and 2011. For example, the proliferation of political parties (more than 600) and candidates led to a 55-page ballot in Kinshasa in 2011.5 The law also included electoral thresholds (the minimum shares of the total vote that parties must win to qualify for seats in the national and provincial legislatures), and increased the non-refundable deposit for national assembly candidates to US$1 000, and almost doubled that of presidential candidates – from US$5 000 to US$100 000.6 These reforms were aimed at addressing some of the structural flaws of the Congolese political system. Typically, they helped reduce fragmentation in the legislature and led to a decrease in the number of smaller parties.7 Since February 2018, smaller parties were compelled to form new electoral coalitions to ensure that they could garner sufficient votes to meet the new electoral thresholds and qualify for seats in future national and provincial assemblies.

On 13 January 2018, the head of CENI, Corneille Nangaa, announced the end of voter registration, which took place between 25 July and 8 August 2017. This was an important milestone in electoral preparations. The DRC government funded a US$400 million voter registration exercise, which recorded over 46 million potential voters (well above the 41 million expected),8 and was seen as a very expensive and complex process. Nonetheless, opposition and other interest groups, such as the Catholic church, cited irregularities in the registration process and challenged the ensuing voter register.

One major issue was the electoral calendar and the limited transition period. The electoral cycle, including local elections, should be completed by 16 February 2020. The timetable was criticised by political and civil society groups as a difficult schedule orchestrated to give Kabila and his ruling party an unfair advantage, as the then ruling party had an upper hand in terms of organisational and resource capabilities. On the contrary, the relatively tight nature of the electoral calendar was seen as disadvantageous to the numerous and fragmented opposition political parties, which needed more preparation time. Despite scepticism about the process, most parties took steps to keep up with the CENI calendar.9

In spite of calls by the international community for him to make public his intentions of not seeking re-election, Kabila remained silent on the topic until his prime minister, Bruno Tshibala Nzenze, announced in June 2018 that Kabila would not seek re-election.10 This announcement helped to calm tensions at the time. The incumbent Peoples’ Party for Reconciliation and Democracy (PPRD) announced Shadary, the former interior minister, as its presidential candidate. This partly resolved earlier concerns and speculation about Kabila’s intentions, and also indicated the selection of a successor whom Kabila trusted to safeguard his family interests in the successor government, as Shadary is known to be close to Kabila.11 While some members of the international community viewed the election calendar as a sign of progress, many Congolese people remained sceptical, citing the rising tensions in the country.12 The country’s history of political conflicts remains a driver of instability, and violent conflict continued in the eastern part of the country.13 The pre-election period was characterised by violent protests and the state responding with excessive force.14

The PPRD has carried out some reforms, including making Kabila the president of the party, among other internal restructuring. These actions and political preparations pointed to a regime strategy that would see Kabila step down but still exercise a degree of control behind the scenes as the PPRD president. Even though Shadary has been beaten to third place in the presidential election, legislative results from the election showed that the Common Front for Congo (FCC), a pro-Kabila coalition, won a majority, with 341 of the 500 seats in the national assembly. This figure exceeds the threshold of 250 seats needed for a majority. Tshisekedi’s Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS) and its allied Union for the Congolese Nation (UNC) only managed 46 seats, while Fayulu’s Lumuka coalition won 94 seats.15

Before the elections, there were some concerns about the transparency and overall outcome of the polls. The Kabila government was operating from a position of relative strength: it retained firm control of the state security and electoral machinery, and was also better resourced than most of the relatively weak and fragmented opposition parties. The Kabila government had a strong footing in the CENI and the Constitutional Court, which arbitrates electoral disputes in the presidential and legislative elections. It also controlled most provincial governments. Furthermore, public perception about the impartiality of the CENI was low. Some local civil society groups described this as a “total crisis of confidence” in the electoral process.16

In addition, there were concerns about preparations for the elections, especially the logistics. In particular, the introduction of new voting technology stirred more controversy. The electoral body envisaged using voting machines instead of printed ballot papers – a change that sought to remedy the logistical challenges encountered in previous elections, particularly lengthy ballots. The opposition and civil society groups were worried that electronic voting machines could lead to voter fraud, and raised issues about voter confidentiality. Other political, technical and financial concerns were also raised. As recounted by a civil society activist: “DRC currently has a population which is 65% illiterate – mostly women and young people – who would consequently have enormous difficulties in using these machines, particularly as they are programmed in the French language, not the local language.”17 Others argued that although the CENI was testing prototypes that were reportedly more reliable, using novel technology potentially posed a risk, given the poor infrastructure and a lack of reliable electricity.18 Notably, there were concerns about financial transparency and the procurement of the machines, their timely delivery and the likely effects on training needed to use them. Some of these concerns were confirmed by the delay in the election process, especially in the collation of the results. The electoral body had to grapple with some logistical challenges – for instance, in early December 2018, one of its warehouses was burnt to the ground, including the thousands of electronic voting machines stored there. Voting was also suspended and delayed in some parts of the country – for example, close to a million people could not vote in states affected by the Ebola outbreak.19

Another contentious issue involved the contenders in the presidential elections. The names of prominent people – such as former vice president, Jean-Pierre Bemba, and Moise Katumbi, an exiled businessman and former governor of Katanga province – surfaced as likely candidates. However, opposition forces accused Kabila’s government of blocking some top candidates from running. Notably, Bemba was a surprise contender after the International Criminal Court (ICC) appeal judges, in June 2018, acquitted him of war crimes committed by his Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC) forces in the neighbouring Central African Republic in 2002 and 2003. Bemba returned to the DRC after more than a decade, and five weeks after his conviction for war crimes was overturned, he was nominated by the MLC as the party’s candidate for the upcoming presidential election.20 However, his candidature was disqualified by the electoral commission, citing a pending case in which Bemba was convicted of interfering with witnesses. This charge has been linked with corruption, as Congolese law prevents people convicted of corruption from running for the presidency. Unsurprisingly, on 3 September 2018, the Constitutional Court upheld the electoral commission’s decision that Bemba could not run because of the pending case at the ICC.21 Congolese authorities also blocked Katumbi, another top opposition contender, from entering the country to register as a candidate. In addition, the Constitutional Court upheld the invalidation of former prime minister Adolphe Muzito,22 but surprisingly, the Constitutional Court reinstated the candidature of former prime minister, Samy Badibanga Ntita, who was accused of having a second nationality.23

A further issue had to do with the role of the international community in the election process. The Congolese government indicated that the election was a purely internal affair and would fully pay for it. Interestingly, MONUSCO was mandated through Resolution 2409 to provide technical assistance and logistical support for the electoral process, in coordination with the Congolese authorities. However, the CENI stated that it would not accept any assistance from MONUSCO.24 The government also indicated that it was not open to having any outside special envoys observing the elections, and demanded an exit strategy for MONUSCO. For various reasons, in April 2018 the government denied the existence of a humanitarian crisis in parts of the country and refused to attend an international conference in Geneva, organised by the United Nations (UN), to raise US$1.7 billion for emergency assistance for over 13 million people in Congo affected by recent violence.25 The country also continued to suffer from recurrent outbreaks of the deadly Ebola virus. The position of the government was seen as part of a scheme aimed at repairing the image of the DRC to make it attractive to foreign direct investment.26 Western governments and local civil society were sceptical about the capacity of the government to bear financial responsibility for the elections – however, the elections did take place, with enormous state funding.

At a regional level, the AU established a small liaison office in Kinshasa and engaged in preventive diplomacy talks with Congolese political actors and regional leaders. The AU Peace and Security Council re-emphasised its support for the implementation of the Saint Sylvester Agreement and called for the region and the wider international community to provide technical, logistical and financial support for the elections.27 The roles of regional powers and neighbours in the election is noteworthy – for example, southern African governments appeared frustrated with Kabila’s failure to cooperate with their election-related initiatives. The DRC government turned down both South Africa and SADC’s offers of technical support that followed a December 2017 visit of SADC officials and election experts.28 Nonetheless, while SADC leaders nudged Kabila toward elections, some leaders of DRC’s immediate neighbours – Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi – seemed not to be directly involved. Interestingly, all three neighbouring countries have manipulated their own constitutions in the past to stay in power, and so have little credibility to push for respect of term limits, despite their security concerns vis-à-vis their borders with the DRC.

The Post-election Environment and Prospects for Democratic Stability

The results of the elections were finally announced after a long delay, amidst tensions and allegations of tampering by different candidates. However, the delay in the release of results was explained by the CENI as being a result of the slow transmission of tally sheets from across the vast country. There were allegations of fraud in the elections, giving the runner-up candidate reason to challenge the results in court, and there were concerns by both local and international actors about the election outcome. The AU called for a recount of the votes – a call that was uncharacteristic of the AU, which rarely criticises election results. Similarly, the ICGLR expressed “great concern” about the controversy. Interestingly, SADC initially called for a recount, only to backtrack later and urge the international community to respect the DRC’s sovereignty, stressing the need for stability in the country. The aftermath of the elections has seemed to give credence to some doubts about the credibility of the CENI. There are allegations that Tshisekedi struck a deal with Kabila to be declared victor, when it proved difficult to rig the election in favour of the FCC. Kabila sought to continue exerting influence behind the scenes.29 Tshisekedi was simply the least-worst option for Kabila and his networks, given Shadary’s manifest unpopularity.30 Indeed, Tshisekedi’s posture towards Kabila after the elections surprised many. During a speech, he referred to Kabila as “no longer an adversary, but instead as a partner in the democratic change in our country”.31

Some regional powers did not publicly congratulate President Tshisekedi, and he has a legitimacy deficit to overcome. As such, the government will likely find it difficult to undertake the many serious reforms that the DRC requires, because of its lack of legitimacy. Dynamics in the near future could be interesting for the new government. Although Kabila has officially stepped down from office, he and his associates will most likely continue to control the levers of power, such as the military and the economic sector. His political coalition, with the majority of seats in the National Assembly, has a voice in the choice of prime minister and cabinet ministers. Furthermore, the outcome of the senate elections in March 2019 seem to have tightened the leash on Tshisekedi, as the FCC won overwhelming control of the senate, with 90 of 108 seats.32 In May 2019, Tshisekedi named Sylvestre Ilunga Ilukamba, former head of the national railway company, as the new prime minister. This appointment comes from a political agreement between Tshisekedi and Kabila.33

The election hurdle has been crossed, amidst some challenges with consequences for political stability in the country. While there are functioning executive and legislative arms of government in place, the DRC remains unstable and underdeveloped, despite being rich in minerals. The country continues to face severe challenges in exercising the essential functions of a state, such as security and sustainable development, and is placed 176th out of a possible 189 on the Human Development Index.34 Deadly epidemics, such as Ebola, continue to break out in the country, and issues of sexual and gender-based violence persist – conflict-related sexual violence against women, girls and boys is rampant.35 MONUSCO has metamorphosed over the years in response to the political developments in the country. Its mission remains essential for meeting the existing security challenges of the DRC – in particular, those posed by armed groups in the east of the country. Nonetheless, there is a gradual disengagement of the mission in tandem with the effective exercise of the full sovereignty of the state over the entire territory.36 It is, however, still unclear how the recent democratic transition can provide an enabling environment for lasting peace in the country, and possibly lead to the end of one of the oldest peacekeeping missions in Africa.

Conclusion

In hindsight, local and international pressure worked to get Kabila to organise elections and respect the constitutional term limit. The delayed elections eventually took place amidst contentious political, financial and technical obstacles. Contrary to the widely held perception of the ruling party holding on to power through elections, the outcome was different in the DRC. The contested elections produced a government with a legitimacy deficit to tackle the DRC’s multiple security and development challenges. Some argue that the acceptance by many players in the international community of the outcome of the January 2019 elections in the DRC in the name of stability, represents a failure to the Congolese people.37 The DRC has benefited from significant international investments over the past two decades to help stabilise the country and the region. The international community must engage in robust preventive diplomacy to address some of the contentious issues still prevailing, and possibly push for important political and institutional reforms that will contribute to building confidence in future electoral processes, and to the consolidation of peace.

Endnotes

- Al Jazeera News (2019a) ‘Felix Tshisekedi Wins DR Congo Presidential Vote: Electoral Board’, 10 January, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/01/> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- BBC News (2019) ‘DR Congo Presidential Election: Church Questions Results’, 10 January, Available at: <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-46827760> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Afrinews (2017) ‘DRC Political Crisis: A Timeline of Events and the Church’s “Saviour” Role’, 5 January, Available at: <http://www.africanews.com/2017/01/05/> Accessed 10 September 2018.

- National Democratic Institute (2018) Assessment of Electoral Preparations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), February 28 – March 9.

- International Crisis Group (2018) Electoral Poker in DR Congo. Africa Report, No. 259, 4 April.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Al Jazeera News (2018a) ‘DRC President Joseph Kabila Will Not Seek Third Term: PM’, 12 June, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/06/> Accessed September 2018.

- International Crisis Group (2017) Time for Concerted Action in DR Congo. Africa Report, No. 257, 4 December.

- Wembi, Steve (2017) ‘Uncertainty as DRC Sets Election Date to Replace Kabila, Al Jazeera, 9 November, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/11/> Accessed 4 September 2018.

- Langevin, Liliane, Lamarch, Natalie, Down, Rebecca and Cimetta, Sara (2018) ‘Democratic Republic of Congo: 2018 Conflict Risk Diagnosis’, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/1551_0.pdf> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- France24 (2018) ‘Catholic Church Denounces “Barbarism” as Death Toll Rises in Anti-Kabila Protests’, 2 January, Available at: <https://www.france24.com/en/20180102> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Africanews (2019) ‘DRC: Kabila’s Coalition Wins Parliament Majority’, 12 January, Available at: <https://www.africanews.com/2019/01/12/> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Sauti Ya Congo (2018) ‘Joint Statement by Citizens Movements and Civil Society Organizations In the Democratic Republic of Congo’, 8 June, Available at: <https://www.sautiyacongo.org/drc-177-ngos-say-no-to-a-3rd-term-of-office-for-president-joseph-kabila> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- VOA News (2018) ‘UN: Right Conditions Needed for Credible Elections in DRC’, Available at: <https://www.voanews.com/a/un-right-conditions-needed-credible-elections-drc/4501481.html> Accessed 10 September 2018.

- International Crisis Group (2018) op. cit.

- Englebert, Pierre (2019) ‘Congo’s 2018 Elections: An Analysis of Implausible Results. African Arguments’, 10 January, Available at: <https://africanarguments.org/2019/01/10/> [Accessed 19 June 2019].

- Africanews (2018) ‘Jean Pierre Bemba Named as Presidential Candidate in DRC’, 16 July, Available at: <http://www.africanews.com/2018/07/16/jean-pierre-bemba-named-as-presidential-candidate-in-drc-the-morning-call> Accessed September 2018.

- Al Jazeera News (2018b) ‘DR Congo Opposition Leader Bemba Barred from Presidential Poll’, 4 September.

- Nyemba, Benoit (2018) ‘Congo’s Top Court Excludes Opposition Leader Bemba from Presidential Election’, Reuters, 3 September, Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Ibid.

- UN Security Council Report (2018) ‘DRC Briefing on the Electoral Process’, 24 August, Available at: <https://www.whatsinblue.org/2018/08> Accessed 12 September 2018.

- Human Rights Watch (2019) ‘Democratic Republic of Congo: Events of 2018. World Report 2019’, Available at: <https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/democratic-republic-congo> [Accessed 1 July 2019].

- Ibid.

- PSC/PR/BR. (DCCLVIII) AU Peace and Security Council, 758th Meeting, Press Statement, 14 March 2018. Crisis Group Interviews, AU Officials, Diplomats, Kinshasa, Addis Ababa and New York, February-March 2018.

- International Crisis Group (2018), op. cit.

- Berwouts, Kris (2019) ‘DRC: President Tshisekedi’s Leash Just Got a Little Tighter’, African Arguments, 3 April, Available at: <https://africanarguments.org> Accessed 3 April 2019.

- Shepherd, Ben (2019) ‘In DRC Election, a Political System Defends Itself’, 14 January, Available at: <https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Kirby, Jen (2019) ‘Congo’s Disputed Election Could Lead to a Historic Transfer of Power – or Violence’, 10 January, Available at: <https://www.vox.com/2019/1/10/18177141> Accessed 19 June 2019.

- Berwouts, Kris (2019) op. cit.

- Al Jazeera News (2019b) ‘DR Congo: President Tshisekedi Names New Prime Minister’, 20 May, Available at: <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/05/> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2018) ‘Human Development Index (HDI)’, Available at: <http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2018> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2018) ‘Responding to Sexual and Gender-based Violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’, Available at: <https://www.who.int/hac/crises/cod/2pager.pdf> Accessed 18 June 2019

- United Nations (UN) (2019) ‘The UN Security Council Extends the Mandate of MONUSCO until 20 December 2019’, 30 March, Available at: <https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/> Accessed 18 June 2019.

- Ibrahim, Mo and Doss, Alan (2019) ‘Congo’s Election: a Defeat for Democracy, a Disaster for the People’, The Guardian,

9 February, Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/feb/09/> Accessed 3 April 2019.