Twenty-five years after the cold war, we are experiencing one of the most peaceful and prosperous eras in the history of humanity, and yet inequality is at its highest level ever and violent intrastate conflicts continue to proliferate across the world. In Africa, inequality and violent intrastate wars overshadow the progress that the continent has made in growing its economies by getting young people into schools and rolling out the necessary infrastructure to create a climate for businesses to grow.

The last five years in Africa have been particularly disappointing in the number of countries that seem to revert to instability and conflict after a period of relative stability. Why is Africa experiencing this apparent reversal of fortunes? In the last 25 years, we have built a formidable global, regional and sub-regional architecture for peace and security. The shift from interstate to intrastate conflict has led to the creation of mechanisms to deal with conflicts that involve not just the opposing armies of two or more states but, increasingly, a combination of states, militia or rebel groups, and civilians.

As a consequence of this change in the nature of conflict and the protagonists, existing mechanisms had to be adapted and new ones created. Peacekeeping departments at the United Nations (UN), African Union (AU) and other intergovernmental organisations had to adapt their peacekeeping doctrines to include protocols on the protection of civilians, respect for human rights, mainstreaming gender into peacekeeping and a host of other initiatives that take into account the fact that civilians are at the centre of conflicts. Mediation has been strengthened with the creation of mediation support units and the preparation of hundreds of mediators. Peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction have become mainstream thinking in intergovernmental organisations.

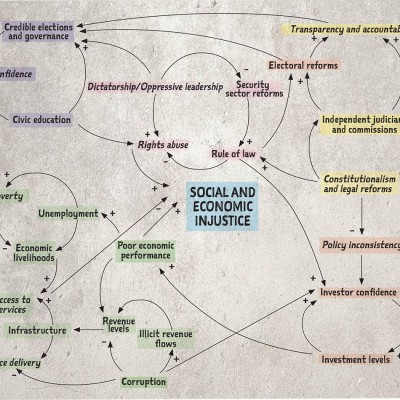

This comprehensive conflict resolution architecture is backed by significant funding and an army of personnel experienced in managing such conflicts. The funding and personnel have been deployed around the world with relative success. The question, then, is why are we still seeing resurgence in these conflicts? The answer lies in understanding the nature of such conflicts, determining where our emphasis has been in attempting to resolve these conflicts, and analysing whether our efforts have been sufficient and correctly deployed.

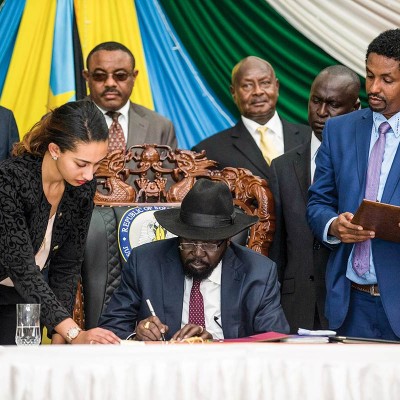

Intrastate conflict requires the external intervention of regional organisations, such as the AU or the Southern African Development Community (SADC), when the conflict reaches a stage where it borders on civil war and threatens to spill over into neighbouring countries, thereby jeopardising global peace and security. It is for this particular eventuality that we have invested so much over the last 25 years in building conflict resolution mechanisms, infrastructure and personnel.

While all these efforts have been valuable and useful in maintaining global peace and security, we have missed one important opportunity to build a more effective response: building local and national capacities for conflict resolution. Many intrastate conflicts have a growth trajectory; they do not just suddenly appear as civil wars. These conflicts begin with some level of dissatisfaction that manifests in low-level peaceful opposition and graduates to street-level protests, which can be peaceful or violent. This state of conflict can fester for years in a country and increase in complexity and intensity over a period of time. By the time it reaches the stage of a civil war, trust and confidence among the protagonists have completely broken down, combatants on all sides may have been killed, thereby hardening attitudes, and the nature of the grievances may have changed and become more complex. At this stage, resolving the conflict becomes much more difficult. Syria is a current case in point.

The gap, therefore, in our elaborate architecture for resolving intrastate conflicts is our lack of investment in building local and national capacities for peace that can be deployed at an early stage to mitigate conflicts before they escalate into civil wars. Respected members of societies who have gravitas, authority and respect, and who stand out as role models, need to be equipped with skills that enable them to intervene in societies to diffuse situations that can explode into violent conflict. Over the next decade, while we strengthen our global and regional instruments to resolve conflicts, we must also build our local and national instruments.