Introduction

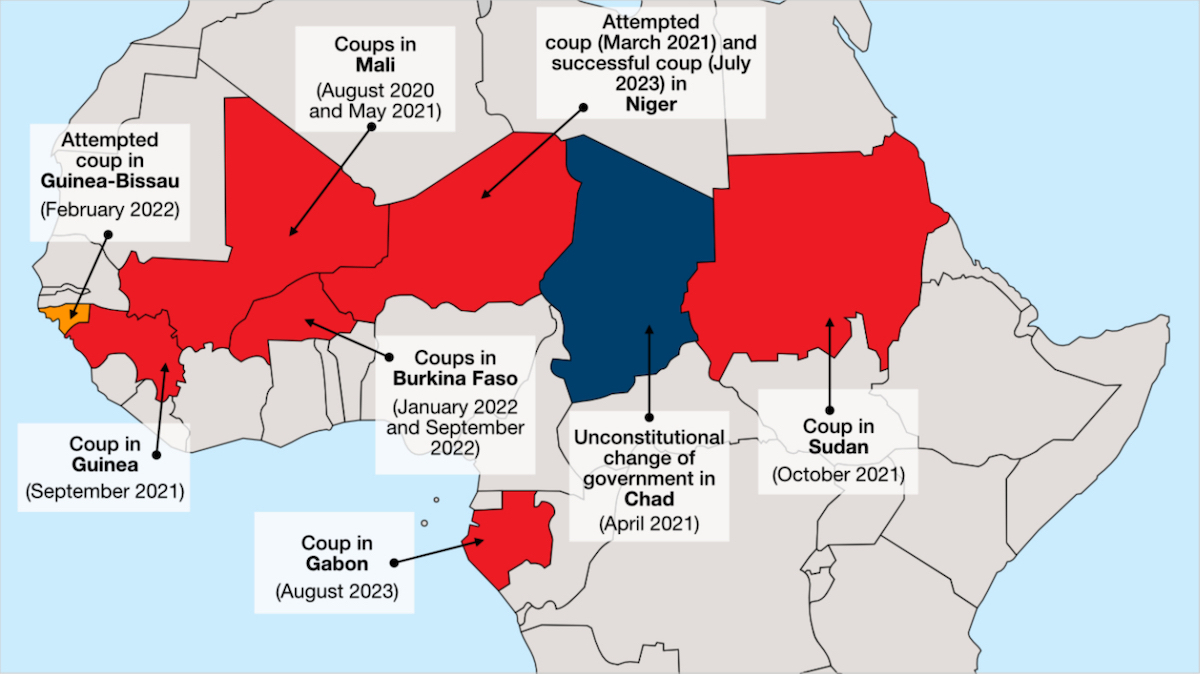

According to the Secretary General of the United Nations (UN), Antonio Guterres, 2021 was a year marked by ‘an epidemic’ of coups.1Michelle Nichols (2012) ‘“An epidemic” of coups, U.N. chief laments, urging Security Council to act’, Reuters, 26 October, Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/an-epidemic-coups-un-chief-laments-urging-security-council-act-2021-10-26 (Accessed 3 May 2022). The Economist noted that 2021 saw more coups than the previous five years combined.2The Economist (2021) ‘As Sudan’s Government Wobbles, Coups are Making a Comeback’, 25 October, Available at: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2021/10/25/as-sudans-government-wobbles-coups-are-making-a-comeback (Accessed 3 May 2022). Scrutinising the data further reveals that the West African region experienced the largest number of military coups, both successful and failed, during 2021 and 2022. There were four successful coups d’état in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso, and failed coup attempts and mutiny in Niger and Guinea Bissau between March 2021 to January 2022. This democratic reversal portends political instability, and its attendant economic consequences for the ECOWAS are concerning considering the developmental agenda of the region.3Mubin Adewumi B. (2021) ‘Political Reforms and Implications for Democracy and Instability in West Africa: The Way Forward for ECOWAS and Member States’, Conflict Trends, Available at: https://www.accord.org.za/conflict-trends/political-reforms-and-implications-for-democracy-and-instability-in-west-africa-the-way-forward-for-ecowas-and-member-states (Accessed 23 April 2022).

The focus of this article is examining measures for strengthening democratic transitions in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso by analysing responses at the national, regional and international levels to ensure rapid restoration of constitutional order. It begins by reviewing the experience of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in supporting democratic transition in the region, while stressing and recognising the interlinkages between defence, development and peacebuilding in laying the foundation for democratisation, peace and sustainable development. The article will advance certain policy prescriptions that entail long-term investments by the international community, and regional and civil society actors in West Africa in the areas of defence, development and peacebuilding, as part of a comprehensive support towards successful democratic transition in the affected countries.

Background

Following the coups in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso, the juntas set up the Charter of the Transition and transitional governments, respectively, and communicated their desire to organise presidential or general elections as soon as possible for a return of civilians to power. But in some countries, respecting the initial schedule seems to be a problem. This was the case in Mali, where another coup struck in May 2021, which saw Colonel Assim Goita being sworn in to lead the transitional government. Analysts have advanced various reasons behind the duration and non-respect of the agenda of the transition after coups in Africa. They have linked this concern to the political ambition of the military in power and to the complex political and security context of the states concerned. Once in power after the coup, the putschists used various means to delay the transition as long as possible.4Delmas Tsafack (2022) ‘The Endless Transitions After Coups in Africa: Democracy in Turmoil’, On Policy Magazine, 27 April, Available at: https://onpolicy.org/the-endless-transitions-after-coups-in-africa-democracy-in-turmoil (Accessed 23 March 2022).

Consequently, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Authority of Heads of States and Government and the African Union Peace and Security Council (AU-PSC) suspended the membership of Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso from their respective institutions and activities, and called, separately, for a restoration of constitutional order within the shortest possible transition period. Furthermore, ECOWAS imposed strict sanctions on Mali, including the closure of land and air borders. However, experience has shown that the use of sanctions stands little chance of leading to sustainable democracy and durable development in the absence of popular support and political and security strategies that address the underlying conditions and drivers of coups. Tensions between ECOWAS and transitional authorities in the aforementioned Member States have not subsided.

While the outcomes of coups d’état in the aforementioned countries are still unfolding, ECOWAS has provided technical support for the transition, particularly in Mali. ECOWAS, working with other actors, supported the Malian authority to develop a workable transition chronogram which can be implemented within an acceptable timeframe. This support was undertaken against the backdrop of the extensive experience of ECOWAS in managing political transitions. ECOWAS’ support for political transitions in Mali after the Captain Amadou Sanogo-led coup in 2012 is instructive. Similarly, ECOWAS supported democratic transition in other Member States, such as Niger (2010), following the military’s seizure of power after President Mahmadou Tandjah attempted an extension of his term limit, and Burkina Faso (2014), after the forced departure of Blaise Compaore. Due to the breakdown of constitutional order in less than a decade, analysts have questioned how effective ECOWAS’ support is.

The circumstances prevailing under the current transitions in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso are debilitating and highly complex. While the three countries suffer entrenched, complex political governance challenges, the situation worsened in Mali and Burkina Faso as these two countries have been confronted with violent extremism and other associated criminal activities. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) figures show that 610 violent incidents took place, mainly involving violent extremist groups, between 25 January and 8 April 2022, in which 567 people in Burkina Faso were killed.5Fahiraman Rodrigue K. (2022) ‘Burkina Faso’s junta under pressure to deliver on security promises’, Institute for Security Studies, Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/burkina-fasos-junta-under-pressure-to-deliver-on-security-promises (Accessed 3 May 2022). Similarly, looking at the 2021 Fragile State Index, affected ECOWAS Member States – notably Mali and Guinea – were categorised as alert countries, while Burkina Faso is characterised as a High Warning country.6Fragile States Index (2021) ‘Fragile States Index Annual Report’, Available at: https://fragilestatesindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/fsi2021-report.pdf (Accessed 2 April 2022). The 2020 Peace Index estimates that the economic cost of violence as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in affected ECOWAS Member States are: Mali (16%), Burkina Faso (14%), and Guinea (4%).7Statista (2020) ‘Economic cost of violence as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in Africa in 2020’, Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1244077/economic-cost-of-violence-as-share-of-gdp-in-africa-by-country (Accessed 3 April 2022). The economic and financial sanctions imposed by ECOWAS and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) on 9 January 2022 considerably clouded the economic outlook for Mali in 2022. Similarly, the rising humanitarian problems in the affected Member States are deplorable. In Mali, the number of internally displaced people (IDPs) increased significantly, bringing the total to over 380 000 people.8World Bank (2022) ‘Internally displaced persons, total displaced by conflict and violence (number of people) – Mali’, Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/VC.IDP.TOCV?locations=ML (Accessed 22 September 2023). Burkina Faso faced the largest forced displacement crisis in the Sahel, accounting for 64% of all displaced people in the region.9Fahiraman Rodrigue K. (2022) op. cit. In West and Central Africa, there were 58 million people in a state of food insecurity.10AU Commission (2022) ‘Statement by H.E Moussa Faki Mahamat Chairperson of the African Union Commission at the Opening of the Extraordinary Humanitarian Summit and Pledging Conference’, Available at: https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20220527/statement-chairperson-african-union-commission (Accessed 20 June 2022).

With violence persisting, the initial euphoria of the coups has subsided, making way for criticism of the new transitional authorities’ inability to restore security.11Fahiraman Rodrigue K. (2022) op. cit. The military as an institution is less capacitated to steer governance in a democratic setting due to its entrenched autocratic institutional tendencies. For instance, many doubted that transitional authorities in Mali would have enough time or legitimacy to undertake extensive reforms.12International Crisis Group (2021) ‘Saving Momentum for Change in Mali’s Transition’, Report No. 304, Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/304-transition-au-mali-preserver-laspiration-au-changement(Accessed 5 May 2022). More importantly, supporting a military-led transition can be challenging as the armed forces can interfere with or exploit emergency situations to further extend their hold of power. For example, the future of political transition is bleak in Guinea. The Transition Charter adopted by Colonel Doumbouya makes the duration of the transition indefinite to the benefit of the ruling military authorities. Article 77 of the Charter indicates that the duration of the transition will be determined by mutual agreement with the national community.

It is noteworthy that managing transitions towards a sustainable democracy is a fundamentally endogenous process, meaning that internal efforts and initiatives should drive the ultimate outcomes. However, the role of international actors such as ECOWAS, the AU and the UN in supporting affected countries is essential in ensuring a successful democratic transition. However, the present focus of these international partners on respecting the transitional timeframe at the expense of long-term efforts aimed at strengthening the state through the interlinkages of defence, development and peacebuilding is likely to achieve marginal results. The crises in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso are an opportunity for the international community to demonstrate their strong political will and commitment to the ideals of collective self-help, democratisation and sustainable development.

ECOWAS, the AU and the UN have a long history of useful and supportive collaboration in conflict prevention, management and resolution activities. This can be further enhanced to support the management of democratic transition. The UN Charter, the Memorandum of Understanding between the AU and RECs on Peace and Security, the ECOWAS Conflict Prevention Framework, and other relevant international instruments recognise the imperatives of coherence, subsidiarity, comparative advantage and complementarity among the UN-AU-ECOWAS peace and security efforts. This approach is necessary for a constructive engagement with the transitional governments in laying the foundation for long-term development by promoting respect for democratic tenets and justice, reinforcing democratic institutions, and helping stable democracy to take hold in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso.

Political transition in West Africa: The context and dynamics

West Africa is home to some of Africa’s stable countries, such as Ghana and Senegal, and several countries have successfully transitioned from war to peace, including Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Sierra Leone. ECOWAS embraces a traditional liberal peace approach to the management of political transition, whereby elections are a necessary step to effective transition. In addition, the regional body prioritised civilian-led transitions guided by an ethos of inclusivity, consensus, justice, dialogue and promptness. However, there have been occasions where ECOWAS has followed a blended method, combining a traditional liberal peace approach with hard military intervention, especially when the affected country has a complex security situation alongside the breakdown of constitutional order. This was the case of the ECOWAS intervention in the political transition in Mali after the Captain Amadou Sanogo-led coup in 2012.

ECOWAS’ intervention in Mali in 2012 is instructive in the regional body’s experience of managing political transition. ECOWAS was the driving force behind the restoration of constitutional order in Mali. It was involved from the Framework Agreement through to the establishment of the Dialogue and Reconciliation Commission and the Preliminary Agreement towards Elections and National Dialogue, which paved the way for the holding of Presidential and Legislative elections in Mali. Also, the ECOWAS-facilitated Transitional Roadmap and the ECOWAS Concept of Operations (CONOPS) served as the basis for the Strategic and Operational frameworks for the international military intervention in Mali in 2012. Notwithstanding these efforts, the request for authorisation of the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) and provision of voluntary and UN-funded logistics support packages to AFISMA, including equipment and services for an initial period of one year, was not heeded by the UN Security Council (UNSC). Nickels argues that the ‘UN and some Western governments declined to back and finance the AU and ECOWAS’ intervention proposals due to concerns about planning and a keenness for non-military options’.13Benjamin Nickels (2013) ‘Analysing the Crisis in the Sahel’, Geneva Centre for Security Policy Paper 2013/3, p. 4. However, others have argued that the UN’s refusal to support ECOWAS and its subsequent takeover mission through MINUSMA demonstrated a lack of acknowledgement of ongoing regional counterterrorism efforts in Mali. In fact, the then US Assistant Secretary for African Affairs, Susan Rice, pointedly queried ECOWAS for referring the matter to the UN when the Region had initially confronted similar challenges in the Mano River Basin on its own.14ECOWAS Commission (2013) ‘The Mali After-Action Review-ECOWAS Initiatives and Responses to the Multidimensional Crises in Mali: Report of the Internal Debriefing Exercise’, Lagos, 28-30 November, ECOWAS Commission. Nevertheless, ECOWAS’ support in other Member States like Niger (2010) and Burkina Faso (2014) enabled a swift return to constitutional order orchestrated under a civilian-led transition.

Reviewing external responses to political transitions in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso

ECOWAS’ diplomatic engagements with transition authorities were critical in reaching some degree of compromise with national stakeholders to facilitate democratic transitions in Burkina Faso, Guinea and Mali. Up to the period of writing this article, ECOWAS has held six Extraordinary Summits and deployed four mediation and follow-up missions to Burkina Faso, Guinea and Mali.

Mali

ECOWAS’ support to engender democratic transition in Mali was underpinned at three levels: diplomatic, technical and political. At the diplomatic level, the ECOWAS Authority appointed H.E. Dr Goodluck Ebele Jonathan, former President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, as Mediator to Mali. Jonathan engaged with the protesters under the aegis of M5-RFP, which insisted on the departure of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. However, the inability of the ECOWAS mediation to strike a comprise between the Keita government and the M5-RFP led to the coup d’état of 18 August 2020. However, through ECOWAS’ mediation efforts, an 18-month transitional government was set up with a civilian prime minister and the transitional authorities agreed to an electoral calendar to restore democracy in January 2022. A coup within a coup occurred in May 2021, which impacted the timeframe for elections. The transitional authority presented a timetable to hold elections within a period of between six months and five years, which ECOWAS found ‘unacceptable’, and the regional body immediately imposed economic and financial sanctions on Mali, including the closure of land and air borders.15At the Extraordinary Summit on 9 January 2022, the ECOWAS Authority imposed tougher sanctions on Mali, including: Recall for consultations by ECOWAS Member States of their Ambassadors accredited to Mali; Closure of land and air borders between ECOWAS countries and Mali; Suspension of all commercial and financial transactions between ECOWAS Member States and Mali, except food products, pharmaceutical products, medical supplies and equipment, including materials for the control of COVID-19, petroleum products and electricity; Freeze of assets of the Republic of Mali in ECOWAS Central Banks; Freeze of assets of the Malian State and the State Enterprises and Parastatals in Commercial Banks; and Suspension of Mali from all financial assistance and transactions with all financial institutions, particularly, EBID and BOAD.

These developments attracted mixed reactions from other international partners. For instance, while the AU-PSC, France, the US, and the European Union (EU) supported and endorsed ECOWAS’ decision to impose additional strict sanctions on Mali, China and Russia blocked the adoption of ECOWAS’ decision at the UNSC. Neighbouring Guinea’s transitional authority recused itself from complying with ECOWAS’ sanction on Mali and declared that the air, land and sea borders of the Republic of Guinea always remain open to all allied countries, in accordance with its Pan-Africanist vision. Similarly, Mauritania, an erstwhile member of ECOWAS, signed a new trade agreement with Mali on 14 February 2022.

The UN Secretary-General and the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) for Mali maintained regular consultations with the transitional authorities to encourage the resumption of dialogue and the submission of a consensual electoral calendar, including through the local transition follow-up committee composed of representatives of ECOWAS, the AU and MINUSMA.16UNSC (2022) ‘Situation in Mali Report of the Secretary-General’, S/2022/278. The EU’s response to the political development in Mali was more severe. The EU imposed targeted sanctions on five individuals believed to be obstructing and undermining Mali’s transition, including Prime Minister Choguel Kokalla Maïga. Amid deteriorating relations with the Malian authorities and the reported deployment in December 2021 of personnel from the Wagner Group, a Russian private security company, France, other European countries and Canada announced the exit of their forces from Operation Barkhane and Task Force Takuba in Mali within six months.

As the security situation in Mali kept deteriorating, the withdrawal of Operation Barkhane and Task Force Takuba created a vacuum in the securitisation of Mali and the Sahel at large. The withdrawal of Mali from the G5 Sahel portended a possible explosion in the regional counter-terrorism collective security arrangement. The commitment of external actors to salvage the Malian situation has been affected by uncertainties as the global political, security, environmental and post-COVID-19 recovery situations have occupied the centre stage of international diplomacy. Specifically, the Russia-Ukraine crisis and its impacts are expected to continue for a considerable time. Although ECOWAS announced the activation of the ECOWAS Standby Force, the regional body would have to rise to its responsibility in providing leadership, as exemplified in the 1990s during the Liberian civil war in mitigating further threats to democratic transition.

Burkina Faso

Since 2015, Burkina Faso has been caught up in a spiral of violence attributed to armed jihadist movements affiliated with Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group, which has left more than 2 000 people dead and 1.8 million displaced. The Damiba-led military authority justified the 24 January 2022 coup d’état by citing the inability of former President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré’s government to provide security in Burkina Faso, although three months after the coup, the military had not been able to reverse the growing insecurity, and incidents of violence occurred almost daily.17Fahiraman Rodrigue K. (2022) op. cit. The fast-declining security and humanitarian situations attracted significant attention from Burkina Faso’s major international partners. In order to facilitate dialogue among all stakeholders, the ECOWAS Authority appointed H.E. Mahamadou Issoufou, former President of the Republic of Niger, as ECOWAS Mediator for Burkina Faso to engage various stakeholders, including the transitional authorities, towards a successful democratic transition in Burkina Faso. In this regard, ECOWAS, in conjunction with the AU and the UN Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), deployed several technical missions to facilitate dialogue between ECOWAS and the transition authorities and to assess the progress made in the process of restoring constitutional order. Consequently, former President Roch Marc Christian Kabore gained partial freedom from detention. Similarly, the ECOWAS Commission provided humanitarian and food aid to IDPs in Burkina Faso. On the other hand, UNOWAS provided support to ECOWAS efforts in assisting the transitional government in Burkina Faso, which is currently facing a difficult security and humanitarian situation.

Guinea

Following a March 2020 constitutional referendum that allowed Alpha Condé to run for a third term and the October 2020 presidential election, which were marred by violence, a coup was staged and President Condé was arrested.18Mubin Adewumi B. (2021) op. cit. Expectedly, the ECOWAS Authority and the AU suspended Guinea from its activities and decision-making bodies. Similarly, ECOWAS imposed targeted sanctions, including travel bans and asset freezes, on the coup leaders and their families.19AU (2022) ‘Final Communiqué of the Extraordinary Summit of the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government on the political situation in Guinea, held on 3 February 2022’. ECOWAS’ negotiations with the transitional authority resulted in the release of President Condé.

While ECOWAS rejected the proposed 36-month transitional timeframe, the AU announced that, through the established Joint Monitoring Mechanism, it would ensure the provision of requisite technical support to the National Transition Council, especially in areas regarding elections support, social cohesion and constitutionalism, which are critical for the establishment of a sustainable post-transition order.20AU (2022) ‘Final Communiqué of the 1064th meeting of the African Union Peace and Security Council on the update on the situation in Guinea, 10 February 2022’. Working with ECOWAS, the AU committed to support the finalisation of an acceptable transition timetable.

Managing democratic transition: Combining defence, development and peacebuilding

As political transitions remain one of the main flashpoints for democratic reversals and the relapse of conflict and violence across the region, the transitions in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso need to be effectively managed and supported while the circumstances prevailing in these countries are complex and debilitating. The context in these countries has necessitated a response to transition settings that combines the predominance and sometimes necessary means of hard security interventions and soft security measures associated with peacebuilding and development responses. Experience has shown that frameworks, tools and investments that focus on the individual pillars of defence, development and peacebuilding concerns in silos are not sufficient to address the growing human security problems in affected countries. A holistic approach that aims at combining each pillar in an integrative manner to take advantage of synergies of the clearly interlinked pillars and avoid challenges is needed.

The current political transitions in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso have further opened the doors of opportunity for the adoption of a comprehensive ECOWAS regional transition and post-conflict/authoritarian reconstruction framework. This framework will incorporate mechanisms and supports to promote a swift return of constitutional order, reconstruction measures and sustainable development plans. These services are best implemented comprehensively at strategic and operational levels, involving actors at all levels – national, regional, continental and global.

Defence

The ECOWAS Member States undergoing political transition continue to suffer from terrorist attacks, with the exception of Guinea. As mentioned previously, the ACLED figures show that 610 violent incidents, mainly involving violent extremist groups, took place between 25 January and 8 April 2022, leading to 567 deaths in Burkina Faso.21Fahiraman Rodrigue K. (2022) op. cit. Despite the deployment of Operation Malico and Operation Kélétigui by the Malian transitional government, the security situation in the country continues to deteriorate.

Drawing lessons from previous ECOWAS’ interventions, deployment of the ECOWAS Standby Force for counterterrorism operations will have to meet certain minimum requirements to ensure a successful outcome. First is the understanding that counterterrorism operations are complex, long term and capital intensive, necessitating huge and sustainable resources to be mobilised for its effectiveness. ECOWAS Member States have to translate their expressed commitment to eradicate terrorism from the region into concrete efforts towards mobilising adequate resources.

The decision to establish a Counterterrorism Fund was a step in the right direction. The ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government arrived at a decision at the Extraordinary Summit on Terrorism held in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso on 14 September 2019 to commit US$2.3 billion to counterterrorism.22ECOWAS (2019) ‘Final Communiqué Extraordinary Summit of the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State and Government on Terrorism, held on 14 September 2019’. While it was agreed by Heads of State and Government that US$1 billion would be mobilised internally from voluntary contributions of US$200 million by each member, the remaining 55% of the funding was requested from external financial mechanisms. However, Member States’ efforts toward mobilising these funds have been marginal. Nigeria and Ghana have reportedly disbursed, respectively, US$80 million and US$20 million directly to support national counterterrorism operations, while only US$20 million and US$5 million were remitted to the regional basket. WAEMU has distributed US$100 million to support counterterrorism in its Member States. Considering that terrorism has increasingly become a threat to all 15 ECOWAS Member States, the mobilisation of this funding is urgent.

The second minimum requirement for the success of ECOWAS’ counterterrorism operations is Member States’ commitment, readiness and capacity to deploy troops. Analysts have criticised ECOWAS troop-contributing countries (TCCs) for not fulfilling their pledge as and when due. However, it should be noted that during the 2012 crisis in Mali, despite logistical, financial and operational challenges, ECOWAS was able to mobilise and deploy over 4 000 troops in a record time of three months.23ECOWAS Commission (2013) op. cit.

Despite a multiplicity of strategies developed by national governments and partners for several years, violence and insecurity linked to terrorism in the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin regions persist and, in some cases, have worsened.24Sampson Kwarkye (2021) ‘Slow progress for West Africa’s latest counter-terrorism plan’, Institute for Security Studies, Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/slow-progress-for-west-africas-latest-counter-terrorism-plan (Accessed 8 June 2022). Therefore, the third minimum requirement is that the deployment of the Emergency Support Function (ESF) for counterterrorism operations be hinged on a functional counterterrorism strategy, which combines both soft and hard approaches to counterterrorism. ECOWAS should leverage the recently adopted ECOWAS Counterterrorism Strategy and its Plan of Actions to complement current initiatives aimed at combatting terrorism in Mali, Burkina Faso and the ECOWAS region at large.

Most importantly, there should be international consensus and support from external actors for the deployment of ECOWAS counterterrorism operations in Mali and Burkina Faso. To attain this, ECOWAS needs to demonstrate effective diplomatic capacity to rally international support around its collective security mission to the affected countries. In this regard, ECOWAS should facilitate a Standing Committee Regional Contact Group to acquire a better understanding of international support, ensure improved coordination among international stakeholders, monitor and follow up on the implementation of decisions, and ensure coherence and consistency.

Development

Many states in the ECOWAS region face severe security problems linked to extreme poverty, economic fragility and inflation – issues compounded by climate security risks.25World Bank (2022) ‘G5 Sahel Region Country Climate and Development Report’, CCDR Series, Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37620 (Accessed 22 September 2023). A cursory look at various coups d’état in the affected countries reveals a direct link between the degradation of governance, the rule of law and human rights, and military takeover. The current transition periods present opportunities at regional and national levels for the adoption of a developmental model that is relevant, appropriate and responsive to address the remote causes and triggers of coups d’état. Regionally, it offers the chance for ECOWAS and other actors involved in the region’s development to synchronise ECOWAS’ Vision 2050, the AU Vision 2063, and the Global Agenda for Development (2030 Agenda) in an integrative, coherent manner, while paying due attention of the realities in Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso and other fragile West African countries. All these agendas should be broken down into simple metrics which resonate with national policymakers and local realities, particularly in Mali, Burkina Faso and Guinea.

At the national level, national development priorities should be inspired by local perceptions, needs, aspirations and priorities to inform policymakers’ understanding and the policy direction of national development. Efforts by transitional authorities to renew the social contract between states and their populations, especially the youth, women and other marginalised groups, should be prioritised. These include the provision of basic social infrastructure and the implementation of development programmes.

Peacebuilding

According to Boutros Boutros-Ghali in his Agenda for Peace, the concept of peacebuilding is to complement the other three important processes of conflict management: preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, and peacekeeping.26Boutros Boutros-Ghali (1992) ‘An Agenda for Peace, Preventive Diplomacy, Peacemaking and Peacekeeping’, Report of the Secretary-General, Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/145749?ln=en (Accessed 8 June 2022). The core objectives of peacebuilding have since been elaborated to include support to political processes; the provision of basic social, health, and educational health services, including the return and reintegration of internally displaced persons and victims of war; restoring core government functions; and economic revitalisation and the rehabilitation of basic infrastructure.27UN (2009) ‘Report of the Secretary-General on Peacebuilding in the Immediate Aftermath of Conflict’, Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/burundi/report-un-sg-peacebuilding-immediate-aftermath-conflict-a63881-s2009304 (Accessed 13 May 2022).

There is a need for ECOWAS, in collaboration with the AU, UN and other development partners, to enhance peacebuilding initiatives in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso. Such initiatives should contribute to enhancing broad participation in transition, promoting institutional reforms, providing technical assistance in conducting credible elections, and promoting social justice, the rule of law, social cohesion, humanitarian support, mediation and dialogue. In implementing these initiatives, development actors need to map out their areas of comparative advantages, while promoting complementarity and subsidiarity in their engagement.

Similarly, in line with the 2012 Secretary-General’s Report on Peacebuilding, the Secretary-General asserts that a successful peacebuilding process requires a wider set of actors — including, but not limited to: representatives of women, young people, victims and marginalized communities; community and religious leaders; civil society actors; and refugees and internally displaced persons — to participate in public decision-making on all aspects of post-conflict governance and recovery.28UN (2012) ‘Peacebuilding in the Aftermath of Conflict: Report of the Secretary-General’, Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/740644?ln=en (Accessed 3 May 2022), p. 11.

Women, youths and victims groups need to be engaged and carried along in the conceptualisation, implementation and review of peacebuilding initiatives in the affected countries.

Conclusion

ECOWAS is confronted with challenges in managing democratic transition in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso. While the regional body does not have a comprehensive regional framework on post-conflict reconstruction to guide its actions towards post-conflict stability, the affected Member States are threatened by an array of issues ranging from poor political governance to underdevelopment and terrorism, particularly in Mali and Burkina Faso. Against this backdrop, it is argued that ECOWAS leadership should act decisively and collectively to address the impending challenge facing these political transitions, in line with established principles of subsidiarity, comparative advantage and complementarity in the coordination of efforts, and collaborate with foreign actors and civil society groups. To this end, policy directions have been discussed around the broad agenda of defence, development and peacebuilding to enhance democratic transition in Mali, Guinea and Burkina Faso.

Mubin Adewumi Bakare