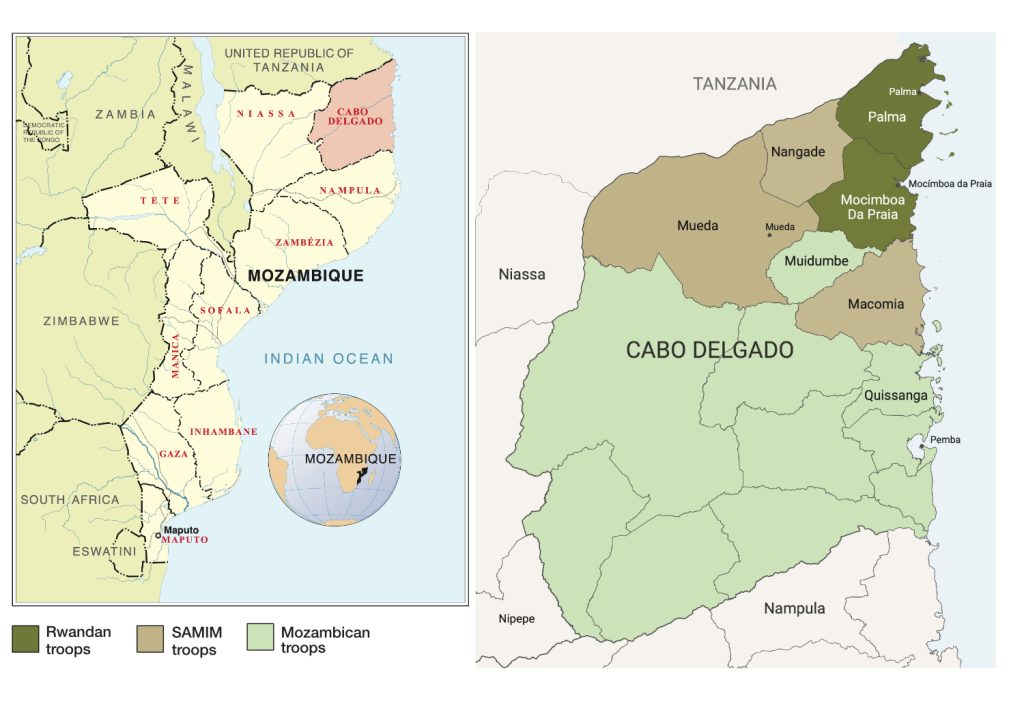

This article is situated in the broader context of the challenges that peacekeeping, peace enforcement and counterinsurgency (COIN) missions are facing in executing their mandates. Although these challenges have been discussed mainly within the United Nations (UN) peacekeeping contexts, they have extended to the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) context. These challenges are noticeable in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, where the Southern African Development Community (SADC) deployed a mission, the SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM), with a counterterrorism mandate. This piece reflects on the lessons from the intervention for both SADC and its member states. The lessons focus on the host state’s consent and cooperation, self-funding, coordination with partners and lastly, host state ownership and responsibility for citizen protection. Both at the macro and micro level, the SAMIM intervention provides critical insights into the emerging ad hoc model for RECs as they assume responsibility for security sector governance architecture following gridlocks in the UN Security Council (UNSC) and the crisis of multilateralism.

Following the UN General Assembly in 2024, which will be remembered for its overarching theme ‘Pact for the Future,’ the piece focuses on how SADC should navigate the aforementioned lessons to enhance sustainable peace and security in the region. Not many studies have focused on how host state consent, self-funding, coordination with partners, and host state ownership and responsibility can affect REC missions like SAMIM. The key question is the commitment of member states to the use of multilateral regional institutions and how these institutions promote the use of their frameworks to tackle common regional security issues while maintaining local agency. Broadly, some questions are: How can SADC and its member states work towards closer cooperation with consistency and in an adaptive manner without compromising the overall mandate of SADC as a regional body? At the same time, how can SADC member states stop viewing SADC as an afterthought in the peace and security sector?

Navigating Host State Consent and Cooperation

When the insurgency in Cabo Delgado broke out in 2017, the Mozambican government resisted SADC involvement and avoided appropriately labelling the situation. Despite a number of Troikas from April 2020, where heads of state suggested the tabling of the situation in Cabo Delgado on the agenda, there was no enthusiasm from Mozambique for the issue to be discussed. Instead, Mozambique turned to alternative actors, such as Russia’s Wagner Group (2019) and the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG), for aid in resolving the security challenge. The militants’ lethal March 2021 Palma attack provided another opportunity for SADC to push for involvement. The Extraordinary Double Troika Summit on 8 April 2021 finally deliberated on an Organ Troika report about escalating terrorism in Cabo Delgado and declared the need for a proportionate regional response.1Dzinesa, G. (2023) ‘The Southern African Development Community’s Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM): Policymaking and Effectiveness’, International Peacekeeping, 30(2), 198-229.

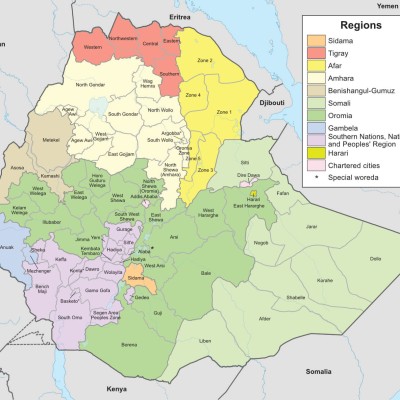

Fig 1: Territorial deployment of Mozambican, SAMIM and Rwandan troops (March 2022)

Eventually, SAMIM was deployed in terms of the SADC Mutual Defence Pact and at the invitation of the Government of Mozambique.2SADC (2021) ‘Experts agree that Foreign Intervention will help Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado to Curb Insurgency’, 11 November, Available at: https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/experts-agree-foreign-intervention-will-help-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-curb-insurgency accessed on 09/07/24 (Date accessed: 12 October 2024). The delayed invitation to SADC came after the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) had already deployed to Mozambique. This demonstrated that Mozambique was disinclined and indisposed to engage SADC, as the regional multilateral body, as the first port of call to deal with the challenges in Cabo Delgado. SADC was considered only after other options had already been deployed. Regarding the principle of sovereignty, there was nothing SADC could have done without the invitation and consent of the Mozambican government. This is enshrined in Article 7 of SADC’s Mutual Defence Pact, which stresses ‘non-interference’ and that the regional body can only act ‘at the State Party’s own request or with its consent.’3SADC (2003) ‘SADC Mutual Defence Pact 2003’, Available at: https://www.sadc.int/document/sadc-mutual-defence-pact-2003 (Date accessed: 12 October 2024).

In addition to the delayed invitation and consent, SADC could not conduct a pre-deployment field assessment (FA) in Cabo Delgado. An FA was critical as, among other things, it would have allowed SADC to gain a deeper understanding of how locals would perceive a multinational force, particularly as such a deployment would come after Rwanda had already deployed. In the first place, and without alleging possible mistrust, such a move reflects a poor willingness of the host state to accommodate a regional force.

SAMIM’s relationship with the host state was not only affected by the delayed invitation and consent, but also by the way it was deployed. SAMIM was deployed to the peripherals of strategic areas of Cabo Delgado. This affected perceptions and the impact of its operations as it saw less action compared to Rwanda, skewing the narrative against its effectiveness. SAMIM was deployed mainly in the Nangande, Macomia and Mueda districts, where its activities were limited. Meanwhile, the Rwandan security forces were assigned to the strategic districts of Palma, the home of Africa’s fourth-largest natural gas reserve, and Mocímboa da Praia, a hub for liquified natural gas development where France’s oil giant Total Energies secured a deal with the Mozambique government. There was nothing SAMIM could do about the situation. As one member of SAMIM’s civilian department stated, ‘What can we do when the host country doesn’t want our help?’4Williams, P. (2024) ‘Multilateral counterinsurgency in East Africa’, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 1-30, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2024.2372712

Was the invitation and consent compromised by the presence of other actors? The host state’s invitation and consent are critical features of any peace operation. It has been noted that limited cooperation fundamentally undermines the ability of missions to deliver on their mandates.5Gregory, J. and Sharland, L. (2023) ‘Host-Country Consent in UN Peacekeeping’, The Stimson Center, Washington DC. The issue is a growing concern, not only for RECs, but for the UN as well. In the stabilisation context, host states use their state sovereignty to push back against the political authority of the UNSC and peacekeeping missions, as they strive for greater oversight of missions.6Ibid. Peacekeeping and peace operations are fundamentally a host state cooperation and partnership endeavour. Their success hinges on the level of cooperation and support received from the host country, as well as the extent to which members of the international community rally behind them.7UNSC (2023) ‘Internal review of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali’, S/2023/36, 16 January.

SAMIM funding: Towards the Self-Help Option?

SAMIM was a self-funded mission with contributions from member states. This was described as a show ‘of the commitment to peace and security, and for using its own resources in addressing and combating terrorism in Cabo Delgado, which is a unique precedent on the African continent.’8SADC (2021) ‘Experts agree that Foreign Intervention will help Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado’, op. cit. Self-funding gave the mission agency to decide on its mandate, when it should start and end, and the overall influence of the mission.

However, SAMIM did face financial challenges, with a number of scholars attributing its withdrawal to a constrained budget. Some scholars and policymakers have opined that predictable funding could have complemented member states’ contributions. Since the passing of UN Resolution 2719 on predictable funding, there has been debate on whether the predictable funding should extend to RECs. However, it should be noted that predictable funding depends on the liquidity of the UN and the cooperation of the United States. The presidential victory of Donald Trump brings much uncertainty to the liquidity of the UN peacekeeping budget. During his last tenure, Trump refused to pay more than 25% of its annual contribution towards peacekeeping. This is one reason why SADC should be careful when receiving external funding. The question lies in the terms and conditions for RECs and SADC when receiving predictable funding as well as who will shape the mandate. If there should be any sort of external funding, SADC should be in control of the content, ideology and doctrine of the mission. SADC should not cede its agency. It should protect itself from external changes in funding structures. The more SADC accepts foreign funding, the more it becomes subject to external ideas about what terrorism is, and the more funders determine the content, ideology and doctrine of the mission. As seen in Afghanistan, Mali and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, money does not guarantee the success of a mission, but rather success comes from focusing on the right problems.

Uncoordinated Parallel Mandates and Plurality of Actors

One of the factors, among others, that contributes to souring the relationship between the host state and multilateral regional bodies is the availability of alternative partners and approaches to peace operations. It has been noted that host states are in a position to choose from a variety of approaches that are beneficial to their interests and ambitions.9Levorato, G. and Donelli, F. (2024) ‘Chronicles of African Engagement: Beyond a Dualist Reading of Foreign Intervention’, African Solutions, 5(1), 1-25. As witnessed in Cabo Delgado, the plurality of the actors present in Mozambique without a coordinated, coherent strategy made things difficult for SAMIM. There are questions about the effects of alternative players on multilateral institutions like SADC in conducting peace operations. SADC was not the only stakeholder in Mozambique. The host state made bilateral agreements with Rwanda and invited the European Union (EU) to train its soldiers. On paper, this would appear as a formidable team that could complement one another’s mandate. However, in reality, there was no coordination and cooperation between Rwanda and SAMIM. It was not known if each actor was familiar with the mandate of the other, as they operated in parallel orbits. The lack of proper coordination resulted in multiple fault lines.

Photo Credit: U.S. government works.

Such situations foster unnecessary suspicions and tension. There existed parallel structures with no shared responsibilities or collective outlook. The general outlook was that of wastefulness and confusion. For example, although deployed in the same province, there was no proper coordination or sharing of strategic information between the Rwandan, SAMIM and host country forces, which resulted in several friendly fire incidents.10Nhamirre, B. (2024) ‘Are Rwandan troops becoming Cabo Delgado’s main security provider?’ ISS Today, 26 September, Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/are-rwandan-troops-becoming-cabo-delgado-s-main-security-provider (Date accessed: 12 October 2024). Failure to coordinate all intervening parties with a shared vision has worked to the disadvantage of the host country as, in the end, it has been left with unresolved problems after the withdrawal of SAMIM.

Ownership and Viable Political and Peace Processes

SAMIM operations lasted three years. It was expected that the Mozambique Defence Armed Forces (FADM) would take over the areas liberated by SAMIM forces upon its withdrawal. FADM received counterterrorism training from the EU Military Assistance Mission Mozambique (EUMAM Mozambique), formerly known as the EU Training Mission in Mozambique (EUTM-Mozambique). The training and support have been in place since 2021, with a focus on protecting civilians and restoring safety and security in the Cabo Delgado province. However, instead of Mozambique assuming greater responsibility and ownership as SAMIM withdrew, Rwanda was requested to deploy an additional 2 000 troops.

Despite the security operations, there were no visible political or peace processes on the ground to address the drivers of conflict by the host state. SAMIM’s counterinsurgency operations only managed to address certain symptoms rather than resolving the deep-rooted causes of the insurgency. Military intervention is just one counterterrorism tool. The withdrawal of SAMIM, although heavily criticised, was commendable. At that point, the host state should have assumed ownership in the context of the peace and stability SAMIM created by addressing the underlying political issues. SAMIM’s shift from an emphasis on military operations (known as Scenario Six) to a multidimensional mission with military, civilian, police and correctional services components (Scenario Five) created an opportunity for the host government to explore political solutions to address the underlying drivers of the conflict.11SADC (2022) ‘SAMIM shifting from Scenario Six to Scenario Five’, 15 September, Available at: https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/samim-shifting-scenario-six-scenario-five (Date accessed: 3 February 2025).

The state has the primary responsibility to provide security to its citizens. That role cannot be handed over to bilateral or multilateral partners permanently. The stabilisation provided by SAMIM was an opportunity to start peacebuilding initiatives by the host country with civil society organisations. SAMIM’s objective was to provide the stability and space needed for the Mozambican government and its partners to address the underlying drivers and causes of the conflict. Was there sufficient interest and recognition for the Mozambican government to address this? SAMIM created moments of stability and improved security, allowing the Mozambican government to provide governance and services and address the underlying causes of the conflict. The inherent challenge for SAMIM was the stabilisation dilemma. The more effective SAMIM was in providing stability in Cabo Delgado, the less incentive there was for the government to address the underlying causes because it viewed the problem as solved.

Recommendations

SADC

- SADC should apply a proactive template in its security sector governance to enshrine the spirit of collective self-defence and collective action. Without it, it risks being side-lined. SADC should recognise that member states cannot effectively address transnational security threats without coordination with the regional body. SADC provides that platform for a collective security outlook.

- There is a cumulative appetite for security-focused and regionally led approaches. As the world oscillates towards RECs as the hub of peace operations, SADC should be ready to herald this new reality by boosting its capacity for delivery and exploring viable partnerships without losing its agency and character. Despite alternative avenues available for member states to deal with peace and security challenges, SADC remains the most viable option. This is because its collective peace mechanisms focus on the region as well as due to its positionality, accrued institutional experience, collective outlook, and political capital in its multilateral disposition. Indeed, its missions have faced tactical and operational challenges, but it remains steadfast in addressing regional security issues.

- SADC’s response to Mozambique’s security challenges exhibited African agency. SADC should work on building mutual trust among member states. The apparent trust deficit exhibited by Mozambique towards SADC should serve as a lesson to avoid complacency and work towards continuous engagement in matters of regional security affecting its members. The situation in Cabo Delgado is an expression of the growing desire of these states to make their own security arrangements, regardless of the existing regional body’s defence and security framework. At the same time, it also represents an increasing recognition of the use of private military companies (PMCs) as part of their security framework.

- SADC should exert greater agency. It should harness the momentum from the SAMIM operations to navigate innovative responses for a peaceful region. SADC needs to be proactive and in sync with conflict curves to avoid creating vacuums that member states fill with alternative actors. SADC has primacy with regards to regional peace and it needs to act as such.

- Military intervention is just one instrument in SADC’s toolbox. There is a need for these efforts to be aligned with preventive and peacebuilding initiatives. SAMIM’s intervention fell short of peacebuilding. Not every problem needs a hammer. SADC should focus on the right problems. In Cabo Delgado, the key was addressing the core drivers of the conflict.

Member states

- The success of SADC’s security framework hinges on the support and cooperation of its members. Member states should prioritise internal peace prevention investments with collective outlook practices. Collective action, collaboration and a renewed commitment to fostering peace in the region are needed. Sustained investments are required for conflict prevention to protect the youth and women and for climate change mitigation and early-warning systems.

- Member states should trust each other and work towards addressing collective security issues, instead of invoking their rights to sovereignty. Tapping into a collective outcome mindset to navigate challenges will develop a sense of ownership and agency in dealing with peace and security challenges. Member states should recommit to the principles and values of collective security enshrined in SADC’s defence protocol. Concomitant security pressures on the European continent make the idea of each region being responsible for its own peacekeeping more attractive.

- Member states should recognise that while alternative bilateral arrangements have specific ulterior motives, SADC’s interests are not narrow and are inspired by broader collective concerns. While member states have the luxury of options, for SADC, it is a duty borne from the broader collective outlook. Thus, delayed consent will affect the effectiveness of the mission and the overall security of the region.

- In cases with spillover potential and a transnational character, the invocation of sovereignty has the potential to prolong the conflict and hinder collective problem-solving. Member states, through SADC, should cultivate mutual trust. Sovereignty should not be used as a deflection and insulation tool to keep the regional body away from the growing crisis.

- Member states should realise that as long as they are members, SADC is a permanent actor in regional affairs. SADC does not have to scramble to find a seat at the table with new security actors in the region. Circumventing the regional framework should not become a norm.

Conclusion

The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, argued in favour of robust regional frameworks and organisations, particularly in regions where long-standing security architectures are collapsing or have never been built. What does this mean for SADC? It should seize the call to foster deeper cooperation with its members in the areas of peace and security. As the world will accelerate towards RECs being dependent in solving their security challenges, SADC should be ready to absorb the coming changes. SAMIM has provided critical lessons for SADC’s future missions. SAMIM was not a secluded outpost as it was viewed in the main peace and security debates. Prevailing scholarly accounts tend to paint it as an inconsequential mission, and many would see it as a footnote in the larger landscape of peace and security. Regardless of these perspectives, this piece has shed light on other perspectives of the mission. The challenges that SAMIM faced should help SADC in planning and future-proofing itself from similar challenges. More importantly, SADC has a major role to play in the regional peace and security sector.