Introduction

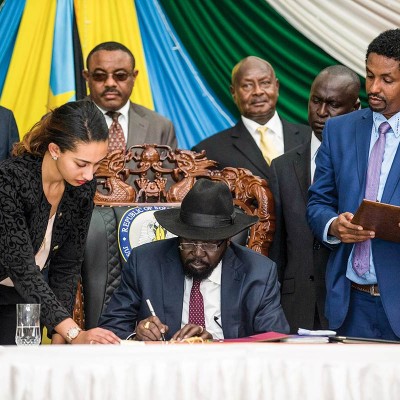

The hope for peace and stability in South Sudan was restored when a peace pact – the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (ARCSS) – was signed between the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement and Army in Government (SPLM/A-IG) and SPLM/A in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO), as represented by President Salva Kiir Mayardit and First Vice President Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon respectively. The agreement, which was signed on 17 August 2015 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and on 26 August 2015 in Juba, South Sudan, was ratified by the South Sudan National Legislative Assembly on 10 September 2015. The agreement sought to end the deadly civil war that had broken out in South Sudan in December 2013, following power struggles between Kiir and Machar and the allegations of an attempted coup made by the former against the latter.

ARCSS culminated in the formation of a Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) on 29 April 2016 with the return of Machar, who had fled Juba following the outbreak of the civil war. However, events on the night of 7 July 2016, less than 48 hours before the celebration of the country’s fifth anniversary of independence, were characterised by violent confrontations in Juba between the SPLM/A-IG and SPLM/A-IO and spread to many parts of the city, resulting in the deaths of many soldiers and civilians as well as the destruction of property and displacement of people. This quick return to violence provoked analysts of conflict and peace studies to rethink and reflect on the processes leading to the signing of the ARCSS. This article analyses the events leading to the conclusion of the ARCSS and the extent to which they undermine the ownership, buy-in and commitment of stakeholders in the South Sudan peace process. It further recommends critical interventions to address identified gaps for securing lasting peace in South Sudan.

Contextualising the 2015 ARCSS

The civil war that broke out in December 2013 came after South Sudan attained its independence in July 2011, as a result of an affirmative secession vote in January 2011. The build-up to the civil war can be traced back to the difficult, strained and uneasy political relationship between Kiir and Machar, both in government and within the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). During the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) interim period from 2005 to 2011, the two political leaders were said to have supported different candidates in the run-up to the envisaged 2010 elections.1

Further factional political struggles within SPLM became rife in 2013 as South Sudan approached its first general elections after independence, which were scheduled for 2015. Machar, together with Pagan Amum Okiech (SPLM secretary-general) and Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior (a fellow member of the SPLM Political Bureau and widow of the late SPLM leader, General John Garang de Mabior), openly criticised the SPLM chairman and announced that they would contest the presidency against Kiir.2 The non-cooperative relations between the Office of the President and that of the Vice President, and contestations over skewed and irregular army recruitments in 2013, were also factors in the civil war, which was triggered by disagreements within the presidential guard over alleged orders to disarm Machar-aligned Nuer members as a result of an alleged coup.3

The conflict was mediated by the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an East African regional integration-inspired organisation premised on Chapter VII of the United Nations (UN) Charter, which provides for regional initiatives in conflict mediation and resolution. The peace talks commenced on 4 January 2015 in Addis Ababa. They were fraught with missed deadlines, although they eventually delivered the ARCSS in August 2015, and this subsequently resulted in the formation of a TGoNU in April 2016. The TGoNU also includes James Wani Igga as second vice president of South Sudan, although he is not a signatory to the ARCSS.

Just prior to the signing of ARCSS, the continued fighting in South Sudan had resulted in a deteriorating humanitarian situation in the country. As an example, the United Nations (UN) reported: “South Sudan faced the worst levels of food insecurity in its history” with “4,6 million people projected to face severe food insecurity during the months of May-July 2015” and “[m]ore than 4,1 million people [were] in critical need of water sanitation and hygiene services”.4 It is against this background that the ARCSS had been negotiated and signed.

It should not be ignored, however, that Kiir reluctantly signed the ARCSS with reservations, amid apparent pressure from the UN Security Council Resolution 2206 (2015) that had “created a system to impose sanctions” on those engaging in, inter alia, “[a]ctions or policies that have the purpose or effect of expanding or extending the conflict in South Sudan or obstructing reconciliation or peace talks or processes, including breaches of Hostilities Agreement”.5 Among other issues, Kiir’s reservations related to the scope of the permanent ceasefire and transitional security arrangements; functions of the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC); amendment procedures for the ARCSS; transitional justice, accountability, reconciliation and healing mechanisms; powers and status of the vice presidents in the TGoNU; the structure and composition of state governorships; power-sharing in the executive; control of the humanitarian and reconstruction initiatives; resource, economic and financial management; and timelines for the reconstitution of the Constituent Assembly within the parameters of drafting the permanent Constitution.6

Kiir’s statement upon the signing of the ARCSS should have sent warning signals to the mediators in Addis Ababa and stakeholders in the South Sudanese peace process about the level of commitment in the future implementation of the agreement. Kiir stated:

With all those reservations that we have, we will sign this [ARCSS] document… some features of the document are not in the interest of just and lasting peace. We had only one of the two options, the option of an imposed peace or the option of a continued war.7

Further, whilst assuring the South Sudanese people that he had “fully committed the government to the faithful implementation” of the ARCSS, Kiir declared in his Public Statement to the Nation with regard to the ARCSS on 15 September 2015:

This IGA [Inter-Governmental Authority] prescribed peace document on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, is the most divisive and unprecedented peace deal ever seen in the history of our country and the African continent at large… This agreement has also attacked the sovereignty of our country… There were many messages of intimidations and threats for me in the last few weeks, to just sign the Agreement silently without any changes or reservations… There is no doubt in my mind that the implementation of some of the provisions of the Agreement will be confronted by practical difficulties that will make it inevitable to review or amend such provisions.8

This statement, when scrutinised thoroughly, would lead one to the inescapable conclusion that the events leading to the conclusion of the ARCSS may have largely undermined ownership, buy-in and commitment of the SPLM/A-IG and other aligned stakeholders to the South Sudanese peace process. His assurances of “full commitment” may be read as political rhetoric in front of an expectant nation and hopeful regional peace brokers.

What further complicates the peace equation are the perceptions and positions in Machar’s political camp. It is instructive to note that even Machar’s SPLM/A-IO had its own reservations about the ARCSS:

We dropped our reservations in favour of peace and he [Kiir] should also drop his reservations in favour of peace. If he [Kiir] has reservations he should keep them to himself like we kept ours to ourselves.9

In reality, Machar’s proposition to Kiir is easier said than done. Whilst the reservations appear to have more to do with competition for power, influence and control by both SPLM/A-IG and SPLM/A-IO, and less to do with how sustainable peace can be secured and how the welfare of the South Sudanese will be transformed, it will be a disservice to the peace process to ignore the respective positions of these key players in the conflict, especially given their influence on the conflict dynamics.

Kiir’s Reservations: Power Politics or Nation-building?

The 16 reservations held by Kiir have largely been swept aside by many analysts and those involved in the South Sudanese conflict. The danger is that they quickly forget how this erodes the SPLM/A-IG’s political will and ownership of the ARCSS. Even in the ARCSS preamble, the parties to the agreement (were expected to) acknowledge “the need to promote inclusivity and popular ownership of this Agreement”, so as to ensure effective implementation.10

One of Kiir’s substantive reservations was on the scope of the permanent ceasefire and transitional security arrangements. Article 5.5 of ARCSS provides for the redeployment of military forces within Juba and outside a 25 km radius from the capital city. Kiir interprets this as the de facto demilitarisation of Juba – yet, according to him, “the army has the responsibility to protect the nation, its people and leadership,” which is a “matter of sovereignty”; hence, it should remain stationed in the capital.11 He adds that the army “protected the capital during a failed coup”.12 His reservations may appear unreasonable, especially given that the ARCSS Article 5 (5.1) has exceptions on presidential guards; guard forces to protect military barracks, bases and warehouses; and Joint Integrated Police – which are enough to defend the sovereignty of South Sudan. Kiir’s insistence that the army protected the capital during a failed coup in December 2013 is against the spirit of reconciliation. This follows revelations in the African Union (AU) Final Report of the AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan that there was not any available evidence to suggest an attempted coup in South Sudan.13 Kiir’s references to the “failed coup” is a signal that mistrust and suspicion will still characterise his working relationship with Machar in the TGoNU.

The SPLM/A-IG also objected to the transition of the monitoring and verification mechanism (MVM), which is responsible for reporting implementation progress of the permanent ceasefire and transitional security arrangements (PCTSA) to the ceasefire and transitional security arrangement monitoring mechanism (CTSAMM). Kiir objected to the MVM role, arguing that its current performance was unsatisfactory as its reports were based on unofficial information, further suggesting that the MVM transition to CTSAMM should only be based on government approval. Whilst the over-reliance on unofficial information or statistics in security reporting can be detrimental to peace efforts – as such information is often over-exaggerated and manipulated in pursuit of narrow sectional interests – there is no justification to eliminate whatever can be useful and positive. Apparently, the work of CTSAMM will be overseen by a more independent and representative Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC), as provided under Chapter VII (2.7) of the ARCSS. Hence, progressive and constructive discussions should be centred on strengthening the JMEC’s capacity to execute its oversight role, instead of contemplating government interference into the transition of MVM. This can be potentially destructive, considering the extent of political polarisation occurring in South Sudan.

Kiir also had reservations on the roles and functions of the JMEC – which, according to Chapter VII (3) of the ARCSS, is responsible for “monitoring and overseeing the implementation of the Agreement and the mandate and tasks of the TGoNU, including the adherence of the parties to the agreed timelines and implementation schedule”.14 He objected to the “overseeing” function – according to him, this would make the JMEC “the governing authority of the Republic of South Sudan”, leaving the government and national legislature uninvolved.15 Further, Kiir commented that the provisions under Chapter VII (5) of the ARCSS – which mandates the JMEC to report regularly in writing to the TGoNU Council of Ministers and the Transitional National Assembly as well as IGAD, the AU Commission, the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) and the UN Security Council (UNSC) on the status of implementation of the Agreement – makes the JMEC “the actual ruling body in South Sudan”.16 Whilst Kiir’s reservations on the JMEC are reasonable, it must be noted that all political parties in South Sudan will be represented in the JMEC and will be part of the deliberations. Moreover, Chapter VII (9) clearly provides that the JMEC quorum “be eighteen (18), of which at least 10 of the members shall be from South Sudan and the other 8 from regional and international groups”.17 This makes the JMEC agenda, proceedings and outcomes national and/or regional in outlook, dispelling sovereignty threats and fears. If the government is made to oversee the functions of the JMEC – an institution that the mediators attempted to make independent and impartial, with minimum interference from the implementers of the ARCSS – it will be tantamount to having the government (SPLM/A-IG and SPLM/A-IO) monitoring and evaluating itself. This would make the JMEC vulnerable and pliant to elite manipulation.

The amendment procedure for the ARCSS, as stipulated under Chapter VIII (Article 4), provides that the agreement can only be amended with at least two-thirds majority in the Council of Ministers and at least two-thirds majority votes of the JMEC. Kiir strongly objects to this, considering this arrangement as “effectively neo-colonialism” and confirming “the supremacy of the JMEC over the TGoNU and national legislature”.18 Here, the SPLM/A-IG’s objections may be motivated by the reality that unilaterally amending the ARCSS may be technically impossible, given that the SPLM/A-IG – just as the SPLM/A-IO – only has two out of 18 members who make up the JMEC quorum. The SPLM/A-IG has 16 ministers out of the total of 30 ministers prescribed by Chapter 1 (Article 10) of the ARCSS to make up the Council of Ministers. The amendment procedure, involving two well-balanced institutions (in terms of composition and structure) in the form of the Council of Ministers and the JMEC, appears to be appropriate as a check and balance mechanism against politically motivated unilateral amendments to the ARCSS. If there are well thought-out and progressive amendments, there is no doubt that the provided procedures will not be a stumbling block.

Kiir also had reservations on the Compensation and Reparation Authority (CRA) provided under Chapter 5 (4), whose role is to manage the Compensation and Reparation Fund for the compensation and reparation of crime victims. He argued that this will be prone to abuse and that instead, the funds should be channelled to “the reconstruction of the infrastructure and rebuilding of livelihoods of communities in the states most affected by the conflict”.19 He cites impracticalities of the same model in Sierra Leone, South Africa, Liberia and Rwanda. Kiir’s fears are understandably justified, given the sensitivities and complexities that are associated with any national healing and transitional justice mechanism. It requires much caution. However, the mere fact that a policy initiative failed elsewhere is not sufficient to justify policy dismissal. Circumstances and contexts differ. In fact, the cited cases of Sierra Leone, South Africa, Liberia and Rwanda should present a golden opportunity for South Sudan to draw lessons and develop a unique model that can be successful. The success of such initiatives is largely dependent upon the political will of the leadership.

Moreover, the idea to compensate victims of war atrocities appears progressive in light of international law obligations derived from declarations such as the Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power (1985); the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984); and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948). This would assist in building the legitimacy of the newest state within the international community. Nevertheless, Kiir’s prioritisation of infrastructure reconstruction and rebuilding the livelihoods of the South Sudanese people should be welcome, unless it is being used as a diversionary tactic to underplay and discount the merits of the compensation and reparation scheme. Generally, compensation and reparation should be seriously considered as essential elements of transitional justice, national healing and reconciliation, and key aspects in any post-conflict situation.

There is also a reservation voiced about having two vice presidents with different statuses. Kiir preferred having two vice presidents with equal status, arguing that having a first vice president and a second vice president would be “a reward for rebellion” and “a humiliation to the [Second] Vice President and his constituency and has the potential to cause more problems in the entire South Sudan”.20 He further objected to power-sharing ratios proposed for the State Council of Ministers in Unity, Jonglei and Upper Nile states, as well as the nomination of governors from Kiir’s Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS), Machar’s South Sudan Armed Opposition (SSAO), Amum’s Former Detainees (FDs) and other political parties – which are collectively referred to as “rebels” by Kiir in his reservations. Kiir’s continued use of the term “rebels” in reference to individuals who will be his partners in government may be interpreted as being against the spirit of accommodation and reconciliation, and this attitude may create sour relations within the TGoNU.

Whether Kiir’s reservations are reasonable and valid, only mediation dialogue and further engagement can establish. Such a dialogue would assist to discern reservations motivated by the desire to gain and retain power, from substantive and genuine reservations driven by nationalist desires to protect the “sovereignty and territorial integrity” of South Sudan, as claimed by Kiir.21

The Status of Implementation of the ARCSS

Since the signing of the ARCSS, there have been calls from both the regional and international community questioning the slow pace at which the peace deal is being implemented. There has been a lack of implementation progress and a violation of prior agreements – notably the Cessation of Hostilities (CoH) Agreement, signed on 23 January 2014; the Agreement to Resolve the Crisis in South Sudan of 9 May 2014; and the Areas of Agreement on the Establishment of the Transitional Government of National Unity in the Republic of South Sudan, signed on 1 February 2015.

In terms of implementation progress, leaders in South Sudan have not been moving as fast as expected when their progress is measured against the milestones stipulated in the ARCSS. The leaders in Juba should be credited for managing to form the TGoNU, as well as constituting the Council of Ministers in April 2016, as provided for in the ARCSS. They have started establishing the necessary institutions of governance provided for in the ARCSS. However, the implementation of other provisions of the ARCSS has been slow.

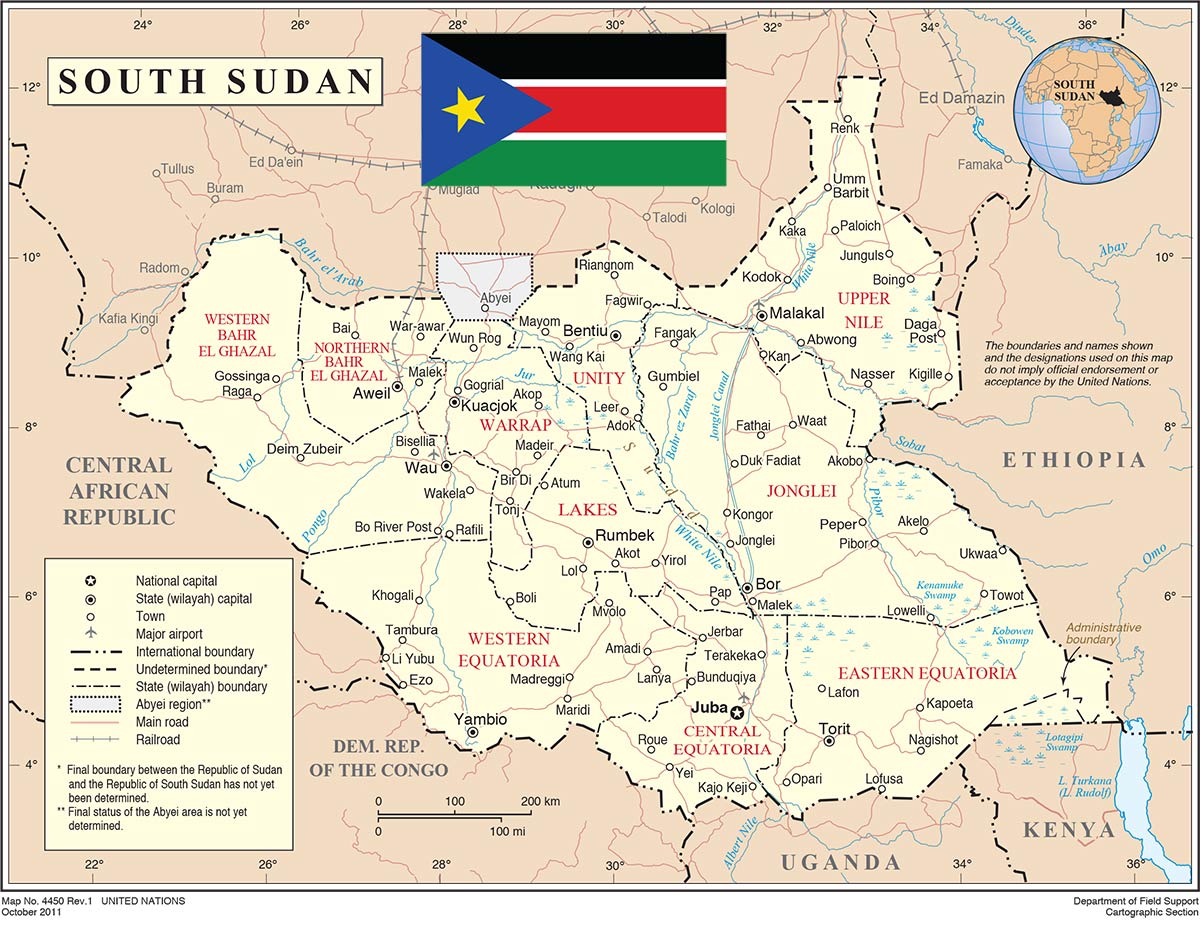

There has been a lack of progress on the formation of the Transitional National Legislative Assembly (TNLA) through the expansion of the existing 300-member National Legislative Assembly by an additional 68 members – comprising 50 members from the SSAO, one member from the FDs and 17 members from other political parties – as provided for under Chapter 1 (11) of the ARCSS. The JMEC also reported that there are disagreements in the selection of the speaker of the TNLA, lack of consensus over the appointment of presidential advisors, and lack of movement with regard to reviewing the 28 states.22 The 28 states were unilaterally created by Kiir after he dissolved the 10 regional states in South Sudan through the issuance of Order 6/2015 on 2 October 2015, with the aim of “devolving power and bringing resources closer to the people, reducing government expenditure and promoting development”.23 However, the decision to create more states has been criticised as a veiled attempt by the SPLM/A-IG “to grab other communities’ land in Upper Nile and Bahr el Ghazal and annex them to the Dinka lands”.24

The CTSAMM – with the mandate, provided for under Chapter II (4) of the ARCSS, of monitoring compliance and reporting to the JMEC on the implementation progress of the PCTSA – is reported to be facing restrictions in doing its work, whilst humanitarian deliveries were reportedly being obstructed in Western Equatoria and Northern Bahr el Ghazal.25 There were reports that CTSAMM monitoring and verification teams in areas such as Yambio, Torit and Juba were being intimidated and restricted in terms of carrying out their operations, with some local authorities demanding to see presidential authority before any access is granted.26

Government departments and offices within the TGoNU appear to be disjointed and lack collaboration. Of course, this is one of the serious challenges any government of national unity faces as interparty trust, consultation, communication, cooperation, dialogue and consensus are difficult to forge. For example, Machar and Igga issued a joint press statement on 1 June 2016 to the effect that the South Sudan presidency – comprising Kiir, Machar and Igga – had agreed to review the 28 states of South Sudan through a 15-member committee, constituted by 10 South Sudanese and five representatives from international partners.27 However, on 3 June 2016, Tor Deng Mawien, a senior presidential advisor to Kiir on decentralisation and intergovernmental linkages, dismissed the press statement whilst denying that consensus had been reached to review the 28 states.28 Such actions may affect the continued effective implementation of the ARCSS.

The slow implementation of the ARCSS is also evidenced by the delays in the formation and reconstitution of transitional institutions and mechanisms, provided for under Chapter 1 (14.1) of the agreement and including, inter alia, the Peace Commission (PC); Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC); Refugees Commission (RC) and other institutions such as the Commission for Truth, Reconciliation and Healing (CTRH); Hybrid Court for South Sudan (HCSS); CRA; and the Board of the Special Reconstruction Fund (BSRF). All these have not yet been established – yet most were supposed to be in place within the first month of the TGoNU, as provided in the ARCSS.

With respect to the National Architecture and Joint Military Ceasefire Commission, the JMEC has also reported that the Joint Military Ceasefire Commission (JMCC), whose mandate under Chapter 1 (3.3) is to oversee and coordinate forces in cantonments and barracks, is not fully operational as its chair is distracted by other commitments. In addition, the Strategic Defence and Security Review Board (SDSRB) is not carrying out its work, as it is failing to reach a quorum with other security institutions such as the Joint Integrated Police (JIP), Joint Operations Centre (JOC) and the Joint Military Ceasefire Team (JMCT). The SDSRB is also failing to perform its functions due to a shortage of working space, and lack of transport and communication essentials.29 However, Festus Mogae, chair of the JMEC, dismissed the explanation that these institutions were failing to operate due to funding shortages, arguing that there was no political will.30

Mogae also noted that the JMCC’s failure to meet and work as a team “impeded the integration of forces”, resulting in widespread violence committed by members of the Shilluk and Dinka communities in Malakal, which culminated in the death of 18 people and injuries to 50 people, as reported in February 2016.31 Again, in March 2016, there was reported violence in Western Equatoria, Central Equatoria, Western Bahr el Ghazal, Malakal and Upper Nile states around March 2016.32 UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon expressed his concern over the fighting between the SPLM/A-IG and SPLM/A-IO in Juba, Wau and Bentiu, as well as reported attacks on the UN and humanitarian operations.33

Due to the reported violence and hostilities in most parts of South Sudan, in March 2016 Ban Ki-moon urged the warring parties to “rebuild mutual trust and confidence from the people and the international community to set the country on a path to stability”. He further implored the South Sudanese leaders to “[p]ut peace above politics” through compromise, so as to bring stability.34

More recently, Ban Ki-moon made remarks at the IGAD Extra-Ordinary Summit in Kigali, Rwanda on 16 July 2016, after reports of renewed fighting in Juba, attacks at UN compounds and the pillaging of UN humanitarian food stocks:

We are all appalled by the magnitude of the violence, the indiscriminate attacks on civilians and peacekeepers, and the immense loss of lives and suffering this crisis has inflicted on the people of South Sudan. The renewed fighting is horrendous and totally unacceptable.35

At the AU Summit in Kigali on 13 July 2016, the AU’s outgoing chairperson, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, also condemned the fighting in Juba:

[O]ver the past few days we see the resurgence of the conflict in South Sudan, after more than two years of talks. Hardly two months after the formation of the Government of National Unity, the belligerents seem to be back in the trenches, and the people of South Sudan, instead of celebrating five years of independence, once again are barricaded in their homes or must flee like sheep before the wolves.36

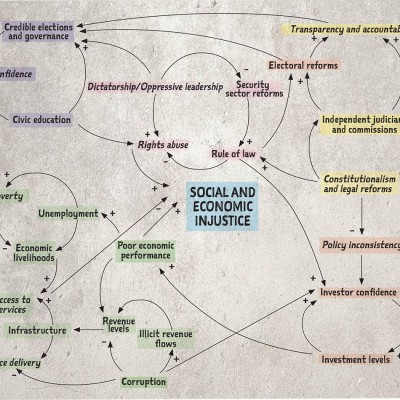

The slow progress recorded in implementing the ARCSS is one of the main causes of this return to violence. Political will has also been singled out by the JMEC as one of the key factors behind this limited implementation progress. The fact that key signatories to the peace deal – specifically Kiir – signed the peace pact with many reservations, obviously has a bearing on his will and commitment to the agreement. This, however, does not in any way downplay the other factors contributing to the limited progress in implementing the ARCSS – notably the struggle for power and control between SPLM/A-IG and SPLM/A-IO leaders Kiir and Machar; the exclusion of other stakeholders to the conflict in the ARCSS negotiation process; and nation-building complexities that naturally face the South Sudanese, as the state is still in its formative stages with very little institutional infrastructure to anchor governance and other systems.

Revisiting the ARCSS: The Way Forward

What any peacebuilding practitioner involved in the peace process in Sudan needs to understand clearly is that South Sudan as a state is still in its infancy. While the country’s politicians have been exposed to numerous peace negotiations and have signed several peace pacts in years dating back to the pre-secession era, it is imperative to note that their exposure to nation-building and governance has been very limited. It is such particularities and nuances of which mediators involved in the South Sudan peace process should be cognisant.

South Sudan has no sound foundational institutions of governance to build on, unlike other African countries that inherited such institutions and simply re-engineered or reconfigured them to suit their new normal. South Sudan is building from an almost clean slate. The institutional infrastructure is weak and its governance culture is new and fragile.

Granted, peace accords do not automatically deliver peace. Particularly in circumstances where the protagonists in the conflict have a history of engaging in confrontational politics, peace agreements will likely be preceded by tensions, suspicions and mistrust. This usually results in selective implementation of the agreement and the violation of certain provisions, which results in the resurgence of conflict. The South Sudanese case fits this scenario, as both Kiir and Machar engage in zero-sum strategies for the purposes of shifting the balance of power in their respective favour. But a defective or controversial peace deal like the ARCSS will compound the situation further and make it difficult for signatories to invest their political will.

UNSC resolution 2206 (2015), which threatened the imposition of sanctions on those obstructing the peace process in South Sudan, may be understandable – especially considering the civilian and uniformed force casualties recorded as protagonists pondered and contemplated signing the proposed peace deal. However, the non-consideration of the 16 reservations made by Kiir, and those held by Machar, are not without any future implications.

It is recommended that the mediators to the conflict and guarantors to the agreement reopen dialogue on the outstanding issues that present as obstacles to the peace process. In addition, in the spirit of inclusivity, local self-defence groups and rebel groups – such as the Arrow Boys in Central Equatoria State and the Tiger Faction New Forces – should be part of the ARCSS as they, together with other community rebels, have been contributing to intercommunal violence.37 Key issues that should be renegotiated with due diligence include security arrangements, power-sharing modalities, and national healing and reconciliation mechanisms. These hold the key to a sustainable peace settlement.

Such negotiations should consider the reservations expressed by both Kiir and Machar. Although some South Sudanese may be losing patience, faith and trust in the two leaders after witnessing episodes of conflicts in the post-independence era, it should be acknowledged that any attempts to exclude these two from any peace process may even worsen the situation. The most important step for mediators, therefore, is to understand the political differences as well as the grievances between Kiir and Machar. These, together with their respective reservations, should be high on the peace agenda, and mediators need to develop a strategy to incorporate their respective issues into the agreement. This will ensure that mutual trust is restored, so that the warring parties are able to work together peacefully.

Conclusion

The durability of peace agreements usually depends on the extent to which the key parties to the conflict exhibit ownership of the peace pact. The imposition of deadlines to force conflicting parties to sign agreements – even in circumstances when the end justifies the means – succeeds in getting signatures on papers but largely fails to secure much-needed peace, as parties are usually reluctant and unwilling to implement actions. As Rudolph Rummel points out, “[T]o make peace is to achieve a balance of powers, an interlocking of mutual interests, capabilities and wills.”38 Thus, negotiating peace agreements requires patience, persistence and determination. Mediators to the ARCSS should engage all the parties to the agreement, and dialogue on the reservations of either side, in such a way that the functioning of the TGoNU in South Sudan is not affected. At the same time, they need to put measures in place to ensure that what has been achieved so far by the South Sudanese TGoNU is not reversed. This is achievable through dialogue and well-negotiated compromises by all the conflicting parties.

Endnotes

- African Union (2014) Final Report of the African Union Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan, 15 October, p. 21.

- Rolandsen, í˜.H., Glomnes, H.M., Manoeli, S. and Nicolaisen, F. (2015). A Year of South Sudan’s Third Civil War. International Area Studies Review, 18 (1), p. 89.

- African Union (2014), op. cit., pp. 21–22.

- African Union (2015) Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Situation in South Sudan. Peace and Security Council 515th Meeting at the Level of Heads of State and Government. Johannesburg, South Africa, PSC/AGH/2(DXV),13 June, p. 3.

- United Nations (2015) UN Security Council Resolution 2206 (2015) [on sanctions compliance and the situation in South Sudan], 3 March, S/RES/2206 (2015), p. 5.

- Government of the Republic of South Sudan (2015) ‘The Reservations of the Government of the Republic of South Sudan on the “Compromise Peace Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan”. Juba, 26th of August 2015′, pp. 4–12, Available at:< http://carleton.ca/africanstudies/wp-content/uploads/GRSS-reservations.pdf> [Accessed 19 June 2016].

- Tekle, Tesfa-Alem (2015) Machar Calls on Kiir to Drop His “Reservations” in Favour of Peace in South Sudan. Sudan Tribune, 28 August, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?iframe&page=imprimable&id_article=56207> [Accessed 1 July 2016].

- Republic of South Sudan (2015) Statement of H.E. President Salva Kiir Mayardit to the Nation on the Agreement of the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan. The Sudan Tribune, 15 September, pp. 2–5, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/IMG/pdf/20150915_statement_of_h._e._presidentsalva_kiir_mayardit.pdf> [Accessed 1 July 2016].

- Tekle, Tesfa-Alem (2015) op. cit.

- Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) (2015) Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan. Addis Ababa, 17 August, p. 3.

- Government of the Republic of South Sudan (2015), op. cit., p. 4.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- African Union (2014) op. cit., p. 27.

- IGAD (2015), op. cit., Chapter VII (3), p. 49.

- Government of the Republic of South Sudan (2015), op. cit., p. 6.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- IGAD (2015), op. cit., Chapter VII (9), p. 49.

- Government of the Republic of South Sudan (2015), op. cit., p. 7.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- Republic of South Sudan (2015) op. cit., p. 3.

- Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission of South Sudan (JMEC) (2016a) ‘Opening Statement as Delivered by H.E. Festus Mogae Chairperson of JMEC During the Plenary Meeting of the Joint Monitoring & Evaluation Commission’, 23 June, Juba, pp. 2–10, Available at: <http://jmecsouthsudan.org/uploads/Chair%20Opening%20Statement%20%2023%20June%2016%20as%20delivered%20-%20web.pdf> [Accessed 28 June 2016].

- United Nations Security Council (UNSC) (2015) Report of the Secretary General on South Sudan (Covering the Period from 20 August to 9 November 2015), 23 November, p. 2.

- Author unknown (2016a) ‘President Kiir’s Advisor Says No Consensus to Review 28 States’, The Sudan Tribune, 3 June, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article59166> [Accessed 29 June 2016].

- JMEC (2016b) ‘Minutes of the 6th Meeting of the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission’, 9 March, p. 2, Available at: <http://www.jmecsouthsudan.com/uploads/minutes9Mar2016.pdf> [Accessed 28 June 2016]; see also JMEC (2016c) ‘Minutes of the 7th Meeting of the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission’, 24 March, p. 2, Available at: <http://www.jmecsouthsudan.com/uploads/Meeting%20Record%20-%2024%20Mar%202016.pdf> [Accessed 28 June 2016].

- JMEC (2016a) op. cit., p. 4.

- Author unknown (2016b) ‘South Sudan Presidency Agrees to Review 28 States’, The Sudan Tribune, 2 June, Available at: <http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article59161> [Accessed 29 June 2016].

- Author unknown (2016a) The Sudan Tribune, op. cit.

- JMEC (2016a), op. cit., p. 6.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- UNSC (2016a) ‘Security Council Press Statement on Malakal, South Sudan’, SC/12252-AFR/3325-PKO/564, 19 February, Available at: <http://www.un.org/press/en/2016/sc12252.doc.htm> [Accessed 26 June 2016].

- United States Security Council Report (2016) ‘Briefing and Consultations on Implementation of South Sudan Peace Agreement’, 30 March, Available at: <http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/south-sudan/> [Accessed 25 June 2016].

- UNSC (2016b) ‘Statement by the Secretary General on South Sudan’, 8 July, Available at: <https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2016-07-08/statement-secretary-general-south-sudan> [Accessed 12 July 2016].

- UN News Centre (2016) ‘Alarmed Over Violence in South Sudan, Security Council Sets Out Steps for Implementation of Peace Deal’, 17 March, Available at: <http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=53475#.V7NORlt97cs> [Accessed 29 June 2016].

- UNSC (2016c) ‘Secretary General’s Remarks at IGAD Extra-Ordinary Summit [as Prepared]’, Kigali, 16 July, Available at: <https://unmiss.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/unsg_kigali_16_07_2016.pdf> [Accessed 17 July 2016].

- African Union (2016) ‘Welcome Remarks of the Chairperson of the African Union Commission, HE Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, 29th Ordinary Session of the Executive Council of the African Union’, Kigali, 13 July, Available at:< http://au.int/en/sites/default/files/speeches/31115-sp-ec_statement_auc_ndz_executive_council13_july_2016.pdf >[Accessed 14 July 2016].

- UNSC (2015) op. cit., p. 2.

- Rummel, Rudoph Joseph (1991) The Conflict Helix: Principles and Practices of Interpersonal, Social and International Conflict and Cooperation. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, p. 221.