Two of the goals set by the African Union (AU) were to promote peace, security and stability for socioeconomic development and to draft an agenda to tackle African problems. The aspiration of African Solutions for African Problems, under the norms of the responsibility to protect (R2P), prompted the AU to take up this responsibility in Somalia. Since the collapse of the state in 1991, Somalia has perpetually failed to secure its territory and protect its populace from self-destruction. It has also failed to respond to disasters, such as famine caused by drought. Somalia is suffering instability caused by Islamist groups who can easily operate in the country due to the absence of state institutions. When the United Nations (UN) Security Council is unwilling to act in a situation crying out for intervention, such as in Somalia, it authorises regional or sub-regional organisations under Chapter VIII of the UN Charter to intervene.1Evans, G. and Sahnoun, M. (2002) ‘The Responsibility to Protect’, Foreign Affairs, 81(6), 99-110, Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/20033347, p. 107. The Security Council passed Resolution 1744 (2007) under this clause, mandating the AU to deploy troops to Somalia in 2007.2UN Security Council (2007) ‘Resolution 1744 (2007)’, S/RES/1744, Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n07/245/31/pdf/n0724531.pdf [Date accessed: 30 December 2024]. The initial mandate to stabilise the country and pave the way for a UN Peace Operation was six months long.3AU (2008) ‘Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Situation in Somalia’, 18 January, Available at: https://archives.au.int/bitstream/handle/123456789/2203/2008_105_R1E.pdf?sequence=1\&isAllowed=y [Date accessed: 30 December 2024]. Regarding interventions, Article 4(h) of the AU Constitutive Act clearly states: ‘the AU has the right to intervene in a Member State according to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.’4AU (2000) ‘Constitutive Act of the African Union’, Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/34873-file-constitutiveact_en.pdf [Date accessed: 30 December 2024], p. 7. As such, the protection of the fundamental rights of citizens is not a purely domestic concern and sovereignty cannot shield repressive states from intervention by the AU. This article in the AU Constitutive Act was invoked after the reluctance of the international community to intervene in Somalia.

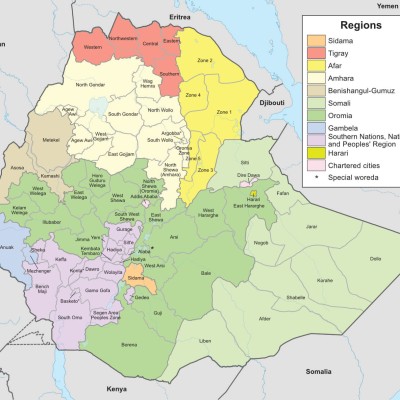

Figure 1: Map of Somalia

The AU Mission to Somalia (AMISOM) continued evolving until it was converted into the AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) in 2022. ATMIS is also expected to transition into a new AU-led Mission in December 2024. The AU conflict resolution efforts in Somalia have gone through several phases: i) establishment and early years (2007-2011); ii) expansion and intensification of operations (2011-2014); iii) expansion of the Mission Area of Operations (AoR); iv) stabilisation and political progress (2015-2017); v) transition, drawdown and end of mandate for AMISOM (2018-2022); and vi) the ATMIS phase (2022-2024).

Beyond 2024, a new AU-led mission is planned with a strong political mandate to respond to Somalia’s security and political realities. Despite the earlier expectation that the Somali National Security Forces (SNSF) would take over the security responsibilities, the reality is that this may not be possible in the near future. In addition, a hasty withdrawal of all the AU peacekeeping troops would reverse the achievements made since 2007 and enable al-Shabaab to regain control over areas it had initially lost to the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) with the support of AU forces.5Gábor, S. and Besenyő, J. (2023) ‘Comparison of the Secret Service of Al-Shabaab, the Amniyat, and the National Intelligence and Security Agency (Somalia)’, International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 36(1), 220-240, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2021.1987143 The FGS continues to experience infighting between political elites, unending terrorist attacks from al-Shabaab, and the inability of the SNSF to take control of the Somali Security Sector.

The AU Peace and Security Council and its role in conflict resolution in Somalia

The AU Peace and Security Council (PSC) is, as per Article 2 of the Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council (2002):

a standing decision-making organ for the prevention, management and resolution of conflicts. The Peace and Security Council shall be a collective security and early-warning arrangement to facilitate timely and efficient response to conflict and crisis situations in Africa.6AU (2002) ‘Protocol Relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union’, Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/37293-treaty-0024_-_protocol_relating_to_the_establishment_of_the_peace_and_security_council_of_the_african_union_e.pdf [Date accessed: 30 December 2024], p. 5.

The deployment of AU troops coincided with the transition from the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) to the AU when its institutions were inward-looking and trying to find their feet, but trying to demonstrate commitment to resolving crises on the continent. Thus, the AU approached the Somalia case with zeal and energy, but lacked the capacity and resources to support a mission of the size required in Somalia.7Interview, with a Somali Analyst, Addis Ababa, 13 November 2023. Acknowledging the challenges, Alpha Oumar Konare, the then AU Commission Chairperson, stated:

I am fully aware of the challenges facing our Organisation, unlike the United Nations, the AU does not have a system of assessed contributions to fund its peace support operations but largely depends on the support of our partners. Thus, rendering the funding of our operations precarious. I am also aware of the limitations of the Commission for its management capacity to oversee large-scale peace support operations, as clearly demonstrated by the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS) operation. Finally, the challenges of an operation in Somalia, a country that has been without a central Government for the past 16 years and where security remains precarious, cannot be underestimated. Yet, the African Union cannot abdicate its responsibilities vis-à-vis Somalia and fail its people. The African Union is the only Organisation the Somali people could readily turn to as they strive to recover from decades of violence and untold suffering. We have a duty and an obligation of solidarity towards Somalia. Furthermore, enhancing the prospects for lasting peace and reconciliation in Somalia will have a tremendous positive impact on the Horn of Africa as a whole, a region that has been and is still plagued by the scourge of conflict and instability.8Konare, A. O. (2007), quoted in: Ani, N. C. (2016) African Solutions to African Problems: Assessing the African Union’s Application of Endogenous Conflict Resolution Approaches, PhD thesis, UKZN, Available at: https://www.academia.edu/31240137/African_Solutions_to_African_Problems_Assessing_the_African_Unions_Application_of_Endogenous_Conflict_Resolution_Approaches [Date accessed: 30 December 2024], pp. 212-213.

The PSC had no working methods nor the autonomy it needed. In the initial years of AMISOM, the PSC was overwhelmed and made numerous requests to the UN to take over the Mission, but the UN refused. AMISOM was also operating against the background of the OAU, which eschewed interventions in the affairs of Member States.9Interview, with a Political Analyst ta the AU, Addis Ababa, 6 September 2023.

The first visit by the PSC to AMISOM was in 2012, approximately five years after the Mission was launched. In the lifespan of AMISOM, the PSC agenda dealt regularly with Somalia and the Mission. All the partners involved in Somalia, including the host nation, were invited to PSC meetings dealing with Somalia and AMISOM. The absence, however, of concrete resource support and the perceived lack of a clear political agenda provided by the PSC to AMISOM affected the AU’s role in Somalian politics. In the evolution of AMISOM, there was a deliberate decision to separate the military track from the overall political process. For quite some time, international partners handled the political track without the security or military dimension. When the military dimension was eventually brought in, the view was that the political process needed to wait while the military dealt with security issues. Unfortunately, this situation, where the military track was dealt with by one organisation and the political track dealt with by another, did not come together at all. The PSC, which had the authority to mandate AMISOM, did not fuse these. There were instances where the PSC pronounced itself on key political issues, like the 2022 elections, but these were few and far between. In 2022, there was infighting among the Somali players, including between the President and the Prime Minister, and the PSC was key in forming the quartet composed of the AU, UN, European Union (EU) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), whose decisions brought about a resolution of the crisis. That event was one of the few instances when the PSC announced its political role and that of AMISOM. The PSC was, unfortunately, inconsistent and not forceful on political matters. It is no surprise then that the FGS does not see any political role for ATMIS.10Interview, with ATMIS Staff, Addis Ababa, 10 November 2023.

Challenges and limitations

The next section delves into the challenges the AU PSC encountered in its efforts to resolve the insurgency in Somalia.

Security challenges

The security situation in which the AU deployed troops is very difficult. There are multiple international stakeholders, including the AU, UN, United States of America (USA), EU and other entities, all involved in efforts to resolve the Somali conflict by supporting the FGS to achieve stability. The multiple players frequently denied the AU the necessary autonomy over its activities11Williams, P. D. (2018). Joining AMISOM: why six African states contributed troops to the African Union Mission in Somalia. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 12(1), 172-192.. Yet, within the security and defence domain, contemporary combat has undergone significant transformation. A significant global challenge confronting governments and security agencies is the increasing prevalence of insurgencies employing non-traditional strategies to disrupt areas, especially in urban areas. Measures against the security issues presented by al-Shabaab include strategies to safeguard metropolitan centres and manage rural areas.12Gaid, S. (2022). The 2022 Somali Offensive Against al-Shabaab: Making Enduring Gains Will Require Learning from Previous Failures. CTC Sentinel, 15, 11.

Al-Shabaab and other insurgencies pose a major security threat because they can operate secretly, hide among civilian populations, and use unconventional methods against regular military troops. These groups frequently employ strategies, including guerrilla warfare, terrorism and propaganda, to accomplish their goals, which can involve weakening governmental authority, instilling fear and instability, or advancing ideological agendas.13Maszka, J. (2017). Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram: guerrilla insurgency or strategic terrorism?. World Scientific. The ever-changing and adaptable nature of insurgency tactics poses a challenge to conventional military methods, thus requiring a holistic approach that integrates security, intelligence, diplomacy and community participation.14Hussein, A. S. M. (2022). International community interventions in Somalia’s conflicts to promote peace and security: Amisom case. Effectively addressing security challenges posed by insurgent tactics, securing urban centres, and managing rural communities necessitates comprehensive and flexible responses that target the root causes of conflict, enhance the resilience of civilian populations, and bolster the capabilities of security forces to counter ever-changing threats.

Operational and logistical challenges

The operational and logistical support provided to AMISOM was partner-heavy. Numerous partners provided support in a variety of areas. In some instances, the support was provided directly to the Troop and Police Contributing Countries (T/PCCs) at the behest of the AU, while in other instances, partners provided support to the same T/PCCs for their participation in AMISOM, albeit on a bilateral basis. However, there was persistent activity from al-Shabaab. The attacks and clashes carried out by al-Shabaab not only endangered the personnel of the operation but also impeded AMISOM’s capacity to establish stability and security in Somalia. The expansive and complex topography of Somalia posed an additional operational obstacle, hindering AMISOM’s ability to encompass and manage the area adequately. Coordination and cooperation among the nations providing troops to AMISOM presented a significant operational bottleneck. The collaboration of nations with diverse military plans and objectives necessitated the establishment of a single command structure. Allegations of human rights violations and misconduct by several AMISOM members further complicated the operational difficulties encountered by the troops.15Wilson, R. J., & Hurvitz, E. S. (2014). Human rights violations by peacekeeping forces in Somalia. Hum. Rts. Brief, 21, 2. AMISOM faced substantial logistical issues due to resource and financial constraints. The Mission functioned with severe financial limitations, which affected its capacity to maintain operations, offer essential assistance to its staff, and efficiently carry out strategic projects. The deficient infrastructure in Somalia, characterised by substandard roads, ports, and airstrips, posed logistical obstacles for AMISOM. The absence of dependable transportation networks posed a challenge in efficiently mobilising troops, supplies and equipment inside the country, affecting the Mission’s logistical capabilities.

Moreover, the distant and secluded characteristics of numerous regions in Somalia presented logistical obstacles for AMISOM. Providing necessary services, supplies, and support to troops stationed in these areas was extremely challenging due to the absence of infrastructure and security challenges. The Mission also faced logistical challenges in maintaining and repairing equipment and vehicles. The limited availability of spare parts and skilled personnel in the region posed significant difficulties in maintaining and sustaining the operational capabilities of AMISOM forces.

Even when international partners provided logistical support, there were challenges in the provision of support. In some instances, partners’ interests and goals did not work in tandem with AU objectives. Partners selected which areas to support, and these were not necessarily in harmony with AU objectives. Partners also often did not share information, which led to the duplication of efforts. The Mission encountered numerous operational and logistical difficulties throughout its deployment in Somalia.

Insurgent tactics, securing urban centres, and managing rural territories

The armed opposition group (AOG) that AMISOM encountered in the mission area most often was al-Shabaab. There were other groups, such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), in Somalia that emerged later and claimed to be linked to the Islamic State of Syria (ISIS). However, al-Shabaab remained a constant threat to AMISOM, the FGS and the broader international community. All AOGs used weapons indiscriminately, thus affecting both Somali civilians and the international community, including AMISOM. Al-Shabaab has used vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED), person-borne improvised explosive devices (PIED), and other types of improvised explosive devices (IED) in conducting attacks. IEDs were mostly used on the roadside and in markets. AMISOM had to secure the main supply routes (MSRs) by increasing the number of patrols conducted in conjunction with local security forces. In this context, AMISOM military personnel were stretched too thin and they could not be everywhere at the same time.

Political and governance challenges in Somalia

Somalia has encountered substantial political and governance obstacles arising from conflict, feeble institutions, and persistent power struggles. These issues are apparent in other areas, such as federalism, local politics, and the role of the AU in Somalia in bolstering government. The implementation of federalism in Somalia has been a source of conflict,16Dahir, A., & Sheikh Ali, A. Y. (2024). Federalism in post-conflict Somalia: A critical review of its reception and governance challenges. Regional & Federal Studies, 34(1), 87-106. as the country shifted from a centralised government to a federal structure. Although federalism has the capacity to facilitate power distribution, inclusiveness, and regional self-governance, it has also resulted in conflicts regarding the distribution of resources, political representation, and the delineation of authority between the central government and regional administrations. The absence of a well-defined structure for federalism intensified conflicts and impeded efficient governance, with the Somali political landscape dominated by the interplay of clan dynamics, patronage networks, and the pursuit of power and wealth. Clan allegiances frequently shape political connections and alliances, resulting in a fractured political environment and challenges in achieving consensus and unity among the many factions. Furthermore, the prevalence of privileged factions and the restricted involvement of marginalised populations have side-lined certain voices and impeded endeavours to foster inclusive governance at the grassroots level. The lack of visibility of an overall AU political strategy in Somalia also influenced AMISOM’s impact in locating itself in the political space in Somalia. This was compounded by the lack of capacity of the political office at Mission Headquarters. The presence of TCCs, whose objectives were not necessarily in harmony with those of the AU and AMISOM, did not help the situation with the host nation. This reinforced the view from the host nation that AMISOM was a purely military operation and had no role to play in the political scene.

The relationship between AMISOM and Somalia was further complicated by the levels of trust between AMISOM and the FGS. The first form of interaction between AMISOM and the SNSF was joint planning and operations in the fight against al-Shabaab. Notwithstanding the provisions in the concept of operations (CONOPs) and the assertion of some Somali respondents that the Somali National Army (SNA) constitutes the first line of offence in AMISOM’s military campaigns, most military operations are not always conducted in a joint manner. Several factors contributed to this, including the limited number of SNA soldiers sufficiently trained to fight, limited communications and military equipment for joint offensive operations, and a lack of trust between some of AMISOM’s TCCs and the SNA/SNSF.17Wondemegegnehu, D. Y. and Kebede, D. G. (2016) ‘AMISOM: Charting a new course for African Union Peace Missions’, Available at: https://worldpeacefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/6.-AMISOM-Yohannes-Kebede.pdf [Date accessed: 30 December 2024].

Funding and resource constraints

AMISOM received its funding from various sources, including the UN Assessed Peacekeeping Budget, UN Trust Fund for AMISOM, AU Peace Fund, AU/AMISOM partners, and most importantly,18Mahmood, O. S., & Ani, N. C. (2017). Impact of EU funding dynamics on AMISOM. Institute for Security Studies. the EU, which paid the allowances for AMISOM personnel totalling approximately €3.6 billion in 15 years. Financing of Peace Support Operations (PSOs) is the singular most important yardstick for measuring their success. Due to the complex nature of AMISOM, its funding mechanisms became highly politicised. The early TCCs, Uganda and Burundi, deployed troops with assistance from the USA, while the AU needed to have its own available resources for deploying the Mission. From 2009 to 2014, the UN allocated over US$1.5 billion to the UN Support Office for AMISOM (UNSOA), which was used to finance various operational expenses. International donors, particularly the USA and the EU, provided voluntary financial assistance and non-monetary resources to the AU and the TCCs. By mid-2015, some bilateral funding arrangements had come under pressure to change ‘owing to a variety of factors, including the longevity of the mission, circumstances in the global economy, and other international crises on the African continent and beyond.’19Hiiraan (2017) ‘Paying for AMISOM: Are Politics and Bureaucracy Undermining the AU’s Largest Peace Operation?’ 16 January, Available at: https://www.hiiraan.com/news4/2017/Jan/139871/paying_for_amisom_are_politics_and_bureaucracy_undermining_the_au_s_largest_peace_operation.aspx [Date accessed: 30 December 2024]. The Mission experienced several funding-related challenges because the AU Member States did not provide the resources required. Tensions arose over disparities in personnel allowances between the AU and UN troops stationed in the mission area and, unfortunately, there was late payment of allowances. Many interviewees indicated that, ‘There have been complaints by several TCCs over delayed payment of allowances to AMISOM peacekeepers in the field, with some claims of troops going without pay for over a year.’20Ibid. The ambiguity surrounding the allocation of funds for AMISOM poses a substantial obstacle arising from donor exhaustion and divergent perspectives on the Mission’s accomplishments in Somalia. The lack of clarity over finance triggered a discussion on foreign assistance and generated concerns about the AU’s accomplishments.

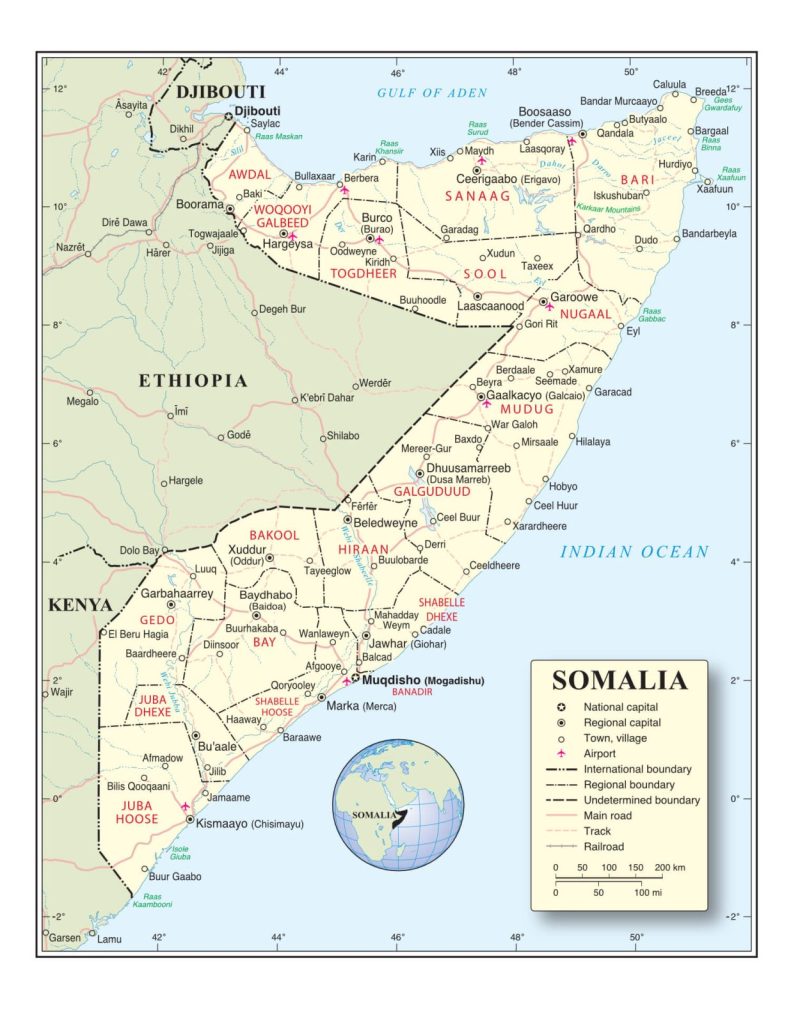

capital of Somalia’s Bay and Bakool Region to see first-hand the impact and progress of UK-funded projects. Baidoa, Somalia (October 2013). AU/UN IST Photo/Mahamud Hassan.

Coordination among AU Member States with international actors

There were various obstacles in coordinating the AU TCCs and the international partners arising from political divergences, conflicting interests, institutional deficiencies, and resource limitations. The AU comprises 55 Member States, each characterised by its own distinct history, culture and interests. The presence of diverse perspectives can provide challenges in reaching consensus on shared goals and approaches, particularly concerning complex matters such as peace and security, economic development, and human rights. The coordination of positions and actions within the AU is made more complex by divergent national interests and competing regional blocs, coupled with the absence of efficient systems for communication and decision-making within the AU.21Byiers, B., & Miyandazi, L. (2022). Balancing Power and Consensus: Opportunities and Challenges for Increased African Integration. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). The institutional architecture of the AU is frequently criticised for its sluggishness, bureaucracy and inefficiency, which can hinder prompt responses to crises and emerging difficulties. The AU’s ability to coordinate activities and engage with external partners effectively is limited by insufficient financial resources and technical capabilities.22Powell, K. (2005). African Union’s emerging peace and security regime: opportunities and challenges for delivering on the responsibility to protect. Institute for Security Studies, Pretoria, ZA. In addition, the collaboration between the AU and global stakeholders, including the UN, USA, EU, regional entities and donor nations, encountered distinct difficulties. The presence of varying mandates, priorities, and operating procedures among different actors can result in the duplication of resources, contradictory tactics, and inconsistent support for initiatives headed by the AU. The presence of competition for influence and resources in Africa adds complexity to establishing effective partnerships and promoting sustainable peace on the continent.

Conclusion

It is clear that despite its resolve to tackle the instability in Somalia, the AU PSC encountered numerous challenges that necessitate adopting a comprehensive approach to enhance institutional procedures, build trust among stakeholders, develop the capacities of national and regional entities, and promote a culture of solidarity and shared responsibility. Resolving financial issues is imperative for ensuring the AU’s efficacy in its efforts to find solutions to the continent’s problems, including peace and security initiatives in Somalia.