Introduction

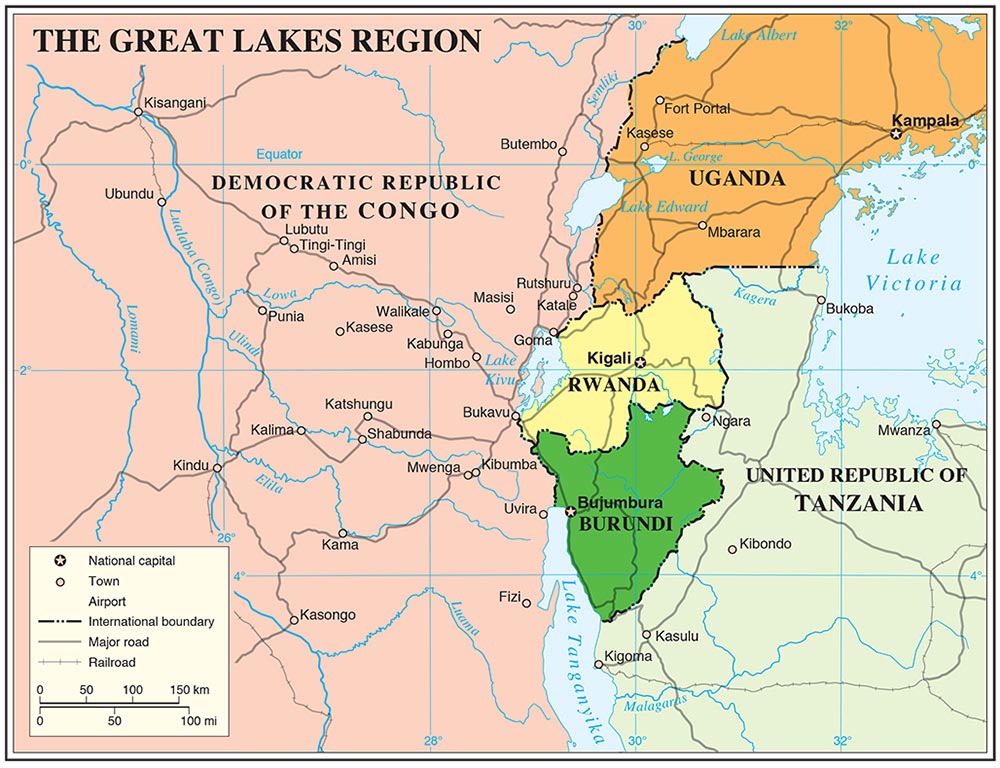

While the name ‘Great Lakes Region’ was derived from the freshwater lakes and river basins within the central and eastern part of Africa,1 for the purposes of this article the Great Lakes Region is defined within the context of the regional entity known as the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR).2 In the ICGLR context, the area of focus is therefore the countries located in the east and central Africa – namely Rwanda, Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, Republic of Congo, Central African Republic (CAR), South Sudan, Kenya and Sudan.3 Thus, the Great Lakes Region constitutes a complex network of political and economic interactions with significant implications for peace, security and governance. It is also a region with interlinked conflicts and common fundamental problems that emanate from post-colonial challenges to state-building and nation-building.

This article analyses the main conflict dynamics in the Great Lakes Region. The causes, dynamics and effects of conflicts are summarised, but the scope of the article does not allow for the exhaustive delineation of the conflict in each country. Rather, the purpose here is to provide an overview of the root causes of conflicts in Great Lakes Region countries, their maintenance factors, their interconnectivity and their consequences on people.

Characteristics of Conflicts in the Great Lakes Region

The classic categorisation of conflicts as interstate and intrastate in the Great Lakes Region seems inapplicable, since the conflicts tend to expand geographically and their epicentre shifts from one locus to another. Furthermore, conflicts in the Great Lakes Region are dynamic and complex, as they involve multiple and interlocking regional and international actors.4 However, these conflicts have common features relating to governance issues, identity division, structural violence, exploitation and equal access to natural resources, which are prominently present. The inability of the governments of the day to manage multi-ethnic societies by ensuring equitable access to natural resources, rule of law and political inclusion creates a ripe context for conflict, as social and political elites play on ethnic divisions and prevailing stereotypes. The difficulties in addressing basic needs for various ethnic groups equitably can be seen within the context of state policies that have been weakened by conflicts, and whose ability to guarantee security of the life and property of its citizens is diminished.5

In addition, conflicts in Great Lakes Region countries have always been interconnected. Although conflicts tend to be intrastate in the beginning, due to strong cross-border dimensions and transnational ethnic identities these conflicts have often spread to destabilise the whole region. Armed groups, including child soldiers, are coerced and driven across borders to fight. Exploitation and the illicit trade of natural resources fuel conflict at a regional level. Small arms and financial resources flow across borders, and people are forced to flee their homes and criss-cross the region to escape violence, starvation and injustice.

Roots Causes and Dynamics of Conflicts

The root causes and dynamics of conflict in the Great Lakes Region are multiple and complex. Inequitable access to state and natural resources, a lack of equal opportunities to access political power and the proliferation of small arms are just a few of the factors that perpetuate conflict in the region. Often, these issues underlie actual or perceived inequalities and grievances between identity groups, which can lead to, among other outcomes, the violent expression of these grievances.6 These factors also relate to structural problems of weak governance and economic mismanagement – such as an unaccountable security sector, debt burdens, unpopular macro-economic policies, the collapse of social services and poor terms of trade. This section will focus on the main causes that trigger conflict in a country, which results in a regional spillover such as ethnic divisions, lack of access to land and natural resources, and democracy and governance challenges.

Ethnic Divisions

Existing literature on conflict in the Great Lakes Region recognises ethnic dynamics as a strong conflict driver in these countries.7 However, it must be noted that the presence of diverse ethnic groups in a specific country, in and of itself, is not sufficient to trigger conflict. Therefore, multi-ethnic societies can prosper on their diversity – as such, ethnic heterogeneity does not breed war, and its absence does not ensure peace. Nevertheless, unlike other countries and regions, conflicts in Burundi, Rwanda, DRC and Uganda have been motivated not by ideology, but typically by ethnicity or by political leaders’ ability to arouse ethnic hostility for their own ends. To understand the regional dimension of ethnicity in the Great Lakes Region, one first has to understand that the ethnic distribution of Hutus and Tutsis is not confined within political boundaries. More than two million Hutus and Tutsis are located across the boundaries of Rwanda and Burundi in neighbouring states. Some trace their ancestry to either the DRC’s North Kivu province (Banyarwanda) or its South Kivu province (Banyamulenge).8 So, once a conflict with an ethnic factor erupts in Rwanda, Burundi or eastern DRC, it is very easy for politicians and other elites who have direct interests to manipulate and exploit these ethnic ties to create alliances, regardless of the boundaries of the three countries.

Inequitable Access to Land

Land use and land access are significant factors in a number of high-intensity conflicts in the Great Lakes Region. In Rwanda, unequal access to land is one of the structural causes of poverty that was exploited by the organisers of the genocide. Limited access to land, exacerbated by its inequitable distribution, and similarly insecurity (brought about by frequent episodes of population displacement and subsequent redistribution of land by the state), have been described as key aspects of the ‘structural conflict’ – patterns of economic domination and exclusion that create deprivation and social tension, and prepare the way for violence.9

Land claim and redistribution was one of the reasons for the failure of the Arusha Agreement (1993), which was supposed to end a four-year war between the government and Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels, and perhaps even prevent the 1994 genocide. Many researchers also consider land disputes to be at the heart of most conflicts in communities. It is estimated that in Rwanda, at district level, at least 80% of disputes reported to administrators are centred on land – and in certain areas, the figure is as high as 95%.10 The National Unity and Reconciliation Committee, which conducted consultations across the country, found that land disputes are “the greatest factor hindering sustainable peace”.11

Inequitable access to land has long been one of several structural causes of conflict in Burundi, and contributes to poverty and grievances against the government and elite groups. In 1993, land disputes related to the return of refugees significantly contributed to the deterioration of the political situation, which culminated in a coup d’état and the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye. Peace in Burundi is still being threatened by inadequate preparation to receive returning refugees and/or ineffective institutions for addressing land disputes, and the fact that grievances related to land are manipulated for political purposes.12

In the DRC, land remains important for several reasons. First, insecure or insufficient access to land in many parts of the east is a significant factor in the impoverishment of thousands of rural people, and is a ‘structural’ cause of conflict. Second, in the case of the Ituri territory, contested purchase and the expansion of agricultural and ranching concessions have been identified as some of the proximate causes of violence,13 and the same may be true in Masisi. Third, the present conflict has radically changed land access patterns through a number of mechanisms, including forced displacement and shifts in the level of authority enjoyed by different customary and administrative leaders. Conflict is producing new competition for land, as part of a wider renegotiation of the local economic space and redrawing of ethnic, class and other ‘boundaries’ between groups.14

Exploitation of Natural Resources

The link between natural resources and conflicts in the Great Lakes Region has been demonstrated by a large number of studies and specialists. According to Le Billon,15 two different types of conflicts in the region are due to natural resources. The first type of conflict is when two or more states engage in an open conflict over the exploitation of natural resources that are present along common borders. The second type of conflict is related to the illegal exploitation of natural resources, which are then used to finance conflicts in the region. Taking precedence has been the role of revenue-generating, non-renewable, lootable natural resources in the regionalisation of insecurity, proliferation of small arms, violent conflict and regional smuggling networks.16

The regional dynamics between natural resources and conflicts have created a security complex due to contextual challenges such as the multiplicity of actors and motivating factors; governance challenges due to a weak state presence, failed regulation enforcement and poor infrastructure; the state of the mining industry, which is largely informal and unregulated; and the prevalence of armed groups in the region, as well as their use of natural resources to finance conflicts.17 As a result, natural resources that should benefit the region – and its people – have been exploited to finance conflict in the absence of the rule of law. The regional dimensions of natural resources in conflict are exemplified by the cross-border activities of illegally armed groups, regional smuggling networks, trade in illegally exploited natural resources, and interstate conflicts over shared natural resources.

Transnational Links and the Diffusion of Violent Conflicts

Research and empirical studies demonstrate that countries surrounded by conflictual neighbours face a higher risk of instability, and even civil war, than those with peaceful neighbours. Studies have pointed out a certain number of factors that play a contaminating role when violence and conflict in one country spreads to its direct neighbouring country. These factors include the division of ethnic groups, refugee flows, transnational arms trafficking, the weakness of ‘infected’ neighbouring states and porous boundaries.18

Naturally, the strength of transnational links and the danger of spreading internal conflict can differ from one country to the next. However, ethnic ties related to strategic alliances are strongly evident in the Great Lakes Region. In fact, in this region the existence of transnational ethnic groups plays an important role in conflict diffusion or escalation.19 For example, Hutu and Tutsi groups that are part of the social structure in Burundi, Rwanda and the DRC were directly involved in the eastern DRC conflicts between 1996 and 2003. After the 1994 Tutsi genocide in Rwanda, Hutus fled en masse into the DRC provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu, where they disrupted an already-volatile situation. They formed alliances with DRC Hutus and Mai-Mai groups against the DRC Tutsis, and created various armed groups to defend themselves. Both parties in conflict could recruit combatants from their ethnic groups in Rwanda, Burundi and the DRC, making the conflict significantly more regional.20

(7 January 2016) (Photo: Gallo Images/AFP/Kudra Maliro)

Another factor that plays a crucial role in spreading conflict from one Great Lakes Region country to another is forced migration flows. At one time or another, every single Great Lakes Region country has received refugees from its neighbouring countries. For example, Burundi has received Rwandan and DRC refugees, the DRC has received Rwandan and Burundian refugees, and Rwanda has received Burundian and DRC refugees. As all these refugees fled conflicts with a strong ethnic background, it was very easy to see how these conflicts spread into the host countries, since there are similar ethnic groups and dynamics across borders. Once in the host country, refugees pose a threat to local stability by fuelling competition over resources such as food, land and jobs. However, the Great Lakes Region has experienced situations where refugees were able to trigger significantly more destabilising dynamics by impacting directly on ethnic relations in their host countries, or by building a base for rebel group mobilisation and operations.21 Some refugee situations have created new conflicts in host countries, while worsening the conflict in their country of origin through cross-border attacks. Once again, the 1994 Tutsi genocide in Rwanda can be used as an example. Following the genocide, Hutus fled to the DRC, and crossed the border with their arms. From refugee camps, they then perpetrated attacks in Rwanda and later on created an armed group, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), which has been destabilising the eastern DRC. FDLR activities have also been a source of tension and conflict between Rwanda and the DRC, and between Rwanda and Burundi.

Democratisation and Governance Issues

The Great Lakes Region has experienced a paradox of democracy and elections triggering violence, instead of entrenching good governance and contributing to stability. Extensive literature on democratic peace suggests that democracies are less likely than other regimes to experience violent conflicts.22 However, it is clear that the process of democratisation seems to be fraught with difficulties, and is often liable to produce violent conflicts in some Great Lakes Region countries. For almost five decades, the more regimes in the Great Lakes Region tried to open up the political arena and implement core democratic and good governance principles – such as freedom of speech, the right to demonstrations, a multiparty system, transparent and fair elections, and accountability – the more violence and conflict were likely to happen. Therefore, in Great Lakes Region countries there is a tendency to move to different forms of benign dictatorships, which are assumed to be more likely to build national unity and preclude ethnic violence than simple democracies. Democracy was imposed on African countries in the early 1990s and seems to have had unexpected results in Great Lakes Region countries. It has produced new tensions and highlighted old grievances relating to social injustices and ethnic differences, which has led to violence and conflicts at national and regional level.23 The question that must be raised is not about the value of democracy as such, but about the preparedness, readiness and ability of Great Lakes Region countries to embrace multiparty democracy in the form it was defined and in the way it has been applied in other parts of the world.

The current sociopolitical dynamics show that generally, political leaders in the Great Lakes Region have noticed that the application of universal democracy was passively correlated to violence and conflicts. They appear to have decided to define democracy in their own way, which is then adapted to the structure, history and development of their societies and people. Therefore, in Great Lakes Region countries, there is a tendency to restrict some democratic rights – such as the freedom of speech and free political activity – in the name of national security, peace and stability. Most importantly, there is also an increasing tendency to change the constitution and remove things such as term limits clauses.24 These moves seek to allow leaders another opportunity to compete and possibly stay in power, so as to sustain the relative security and peace their countries have been enjoying during their political mandate. In some cases, citizens are allowed to vote for or against the change of the constitution through a referendum. Though consultation with citizens before any constitutional change is always considered as the application of a core democratic principle, its validity depends on the context and conditions in which the referendum vote is organised. The remaining crucial question is whether the new way of defining democracy in Great Lakes Region countries will be another significant underlying cause of further conflict, either in the near future or in the long run.

Effects of Conflicts in the Great Lakes Region

Violent conflicts in Great Lakes Region countries – especially in the DRC, Rwanda and Burundi – have inflicted enormous cost at national and regional level. For example, in Burundi, following the attempted coup in 1993, the conflict claimed about 300 000 lives and more than 800 000 people had to flee their homes.25 Its current political crisis – relating to disputes over the 2015 election-related outcomes and respect of the constitution and the Arusha Agreement26 – has already claimed about 400 lives and resulted in 175 000 refugees.27 In Rwanda, the genocide claimed more than 800 000 victims and resulted in more than 2 000 000 refugees.28 And since 1996, the eastern part of the DRC has been the scene of violent conflicts perpetrated by internal and external armed groups, which claimed around 6 000 000 lives and forced more than 2 000 000 people to flee their homes.29 Not only have these conflicts in the Great Lakes Region impacted negatively and severely on civilians, they also have a huge emotional cost for survivors and perpetrators and further facilitate the perpetuation of the cycle of violence by provoking reprisals and counter-reprisals.

Conflicts in the Great Lakes Region have also caused extensive damage to public and private infrastructure. They constitute a massive burden on the economy, especially in Burundi, the DRC and Rwanda, where national economies are already too weak and fragile to meet production requirements and support the institutions of a modern state. Finally, the negative consequences of conflicts in the Great Lakes Region are not limited to the national level. Most of the time, a violent confrontation within a state or society has negative regional effects: criminalisation of the regional economy, drug and mineral trafficking, money laundering, arms flow, and the use of mercenaries and armed groups to destabilise neighbouring weak states with fragile institutions.30

Conclusion

Great Lakes Region countries – especially the DRC, Rwanda and Burundi – partly differ in terms of their history, extent of war and levels of development, but they have some similarities that may explain their interconnected endemic violent conflicts. In terms of democracy and governance, they have been struggling to establish a consensual electoral system which would, inter alia, guarantee a peaceful transfer of power. They also seem to have failed to establish inclusive political institutions, thus resulting in unequal representation in decision-making and access to land and natural resources. They are polarised along identity and ethnic dimensions that are regionalised and manifest in political violence.31 Transnational ethnic groups and porous boundaries facilitate the ‘inter-contamination’ of violent conflict. For example, the genocide in Rwanda increased cross-border ethnic affiliations between it, the DRC and regional ethnic-based rebel groups. It further resulted in a significant number of ‘warrior’ refugees, who destabilised Rwanda and the eastern part of the DRC at the same time. The instability in the eastern DRC then gave Burundian armed groups the opportunity and a rear base to attack their country. Furthermore, the availability of land and mineral resources in the DRC resulted in enormous economic interests for neighbouring and other countries, who benefit from the illegal trade of minerals during civil wars. Similarly, massive displacements and refugee flows across borders in each Great Lakes Region country also spreads the effects of the conflicts within and across neighbouring countries.

Finally, the analysis in this article is incomplete in explaining all possible root causes and dynamics of conflicts in the Great Lakes Region. Although the factors that have been identified as root causes of conflicts are important and tap into broader processes generally recognised in conflict literature to be conflict-generating, others factors such as extreme poverty, climate change and historical and colonial legacy would also be major sources of conflict in the Great Lakes Region.

Endnotes

- Khadiagala, G. (2006) Security Dynamics in Africa’s Great Lake Region. London: Lynne Rienner.

- The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) is an intergovernmental organisation of the countries in the African Great Lakes Region that seeks to promote sustainable peace and development.

- These countries are currently member states of the ICGLR.

- Ansorg, N. (2011) How Does Militant Violence Diffuse in Regions? Regional Conflict System in International Relations and Peace and Conflict Studies. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 5(1), pp. 173–187.

- Van Leeuwen, M. (2008) Imagining the Great Lakes Region: Discourses and Practices of Civil Society Regional Approaches for Peacebuilding in Rwanda, Burundi and DR Congo. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 46(3), pp. 393–426.

- Ewald, J., Nilsson, A., Närman, A. and Stí¥lgren, P. (2004) A Strategic Conflict Analysis for the Great Lakes Region. Stockholm: Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) (Department for Africa).

- Wimmer, A. (1997) Who Owns the State? Understanding Ethnic Conflict in Post-colonial Societies. Nations and Nationalism, 3(4), pp. 631–665.

- Amici, R. (1999) Conflict Resolution in the Great Lakes Region. Conference Report. London: The Council of the Democratic Federal Republic of Congo.

- Uvin, P. (1998) Aiding Violence: The Development Enterprise in Rwanda. West Hartford: Kumarian Press.

- Thompson, N. (2003) Access to Land in Post-conflict Situations: An Analytical Paper. Rome: FAO.

- De Lame, D. (1996) Une Colline entre Mille Ou le calme avant le tempete: Transformations et Blocages du Rwanda Rurale. Musee Royale de L’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren.

- Lind, J. and Sturman, K. (eds) (2002) Scarcity and Surfeit: The Ecology of Africa’s Conflicts. Nairobi/Pretoria: African Centre for Technology Studies/Institute of Security Studies.

- Lobho Lwa Djugudjugu, J.P. (2002) La problématique du conflit ethnique Hema-Lendu en Ituri. Mouvements et Enjeux Sociaux, 7, pp. 43–77.

- Le Billon, P. (2001) The Political Ecology of War: Natural Resources and Armed Conflict. Political Geography, 20, pp. 561–584.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Githaiga, N. (2011) Regional Dimensions of Conflict in the Great Lakes. Report of the ISS Workshop, held at the La Mada Hotel, Nairobi, on 12-13 September.

- Esty, D.C., Goldstone, J.A., Gurr, T.R., Surko, P. and Unger, A.N. (1995) State Failure Task Force Report. McLean, VA: Science Applications International Corporation.

- Lake, D.A. and Rothchild, D. (1998) Spreading Fear: The Genesis of Transnational Ethnic Conflict. In Lake, D.A. and Rothchild, D. (eds) The International Spread of Ethnic Conflict: Fear, Diffusion, and Escalation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, chapter 1, pp. 3–34.

- Weiss, H. (2000) War and Peace in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Current African Issues, 22.

- Lischer, S.K. (2005) Dangerous Sanctuaries: Refugee Camps, Civil War and the Dilemmas of Humanitarian Aid. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Bunce, V. (2005) Democracy and Diversity in the Developing World: The American Experience with Democracy Promotion. APSA Conference on Difference and Inequality in Developing Societies, held in Charlottesville, VA.

- Mansfield, E.D. and Snyder, J. (2005) Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- In Burundi, Rwanda, the DRC, Congo and Uganda, the constitution that was changed – or is in the process of being changed – has a two-term presidential limit.

- Brachet, J. and Wolpe, H. (2005) Conflict-sensitive Development Assistance: The Case of Burundi. The World Bank Social Development Papers: Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction, pp. 1–2.

- Another term of the current president obtained after the 2015 elections – considered by the opposition as a third term (unconstitutional and violating the 2000 Arusha Peace Agreement), and by the ruling party as a second term (legal and constitutional) – has triggered a violent conflict.

- IRIN (2016) ‘Uganda Feels the Strain of the Burundi Crisis’, Available at: <http://www.irinnews.org/report/102350/uganda-feels-the-strain-of-the-burundi-crisis>.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2001) State of the World’s Refugees 2000. Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action. Oxford: Oxford University, p. 246.

- William, B.H. (2015) The Colour of Grace: How One Woman’s Brokenness Brought Healing and Hope to Child Survivors of War. New York: Howard Books, pp. 285–286.

- Ould-Abdallah, A. (1997) Burundi on the Brink 1993–1995. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- Van Leeuwen, M. (2008) op. cit., pp. 430–432.