Introduction

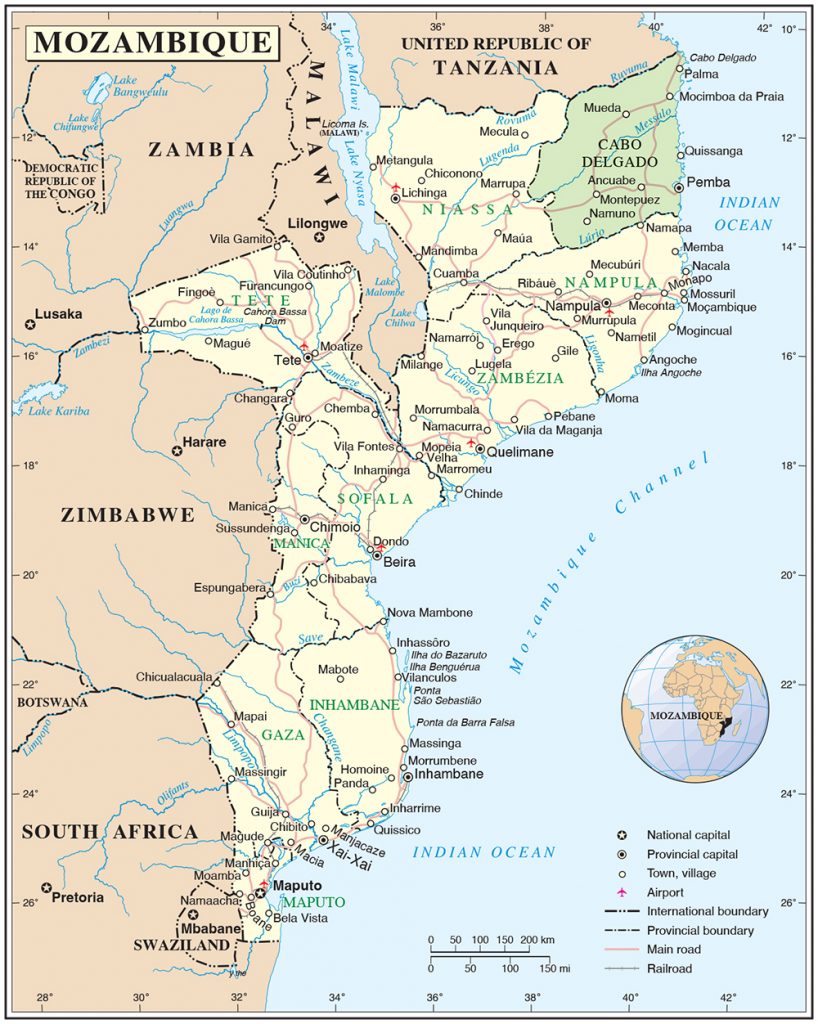

The ongoing militant insurgency and conflict in the upper north-eastern Cabo Delgado province in Mozambique has been brewing since 2017. However, it only gained the attention of the international community in mid-August 2020 when the Islamist extremist movement, Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah (or Ansar al-Sunna), captured the port town of Mocimboa da Praia in the north-eastern part of the country. This was not the first capturing of the town, as the insurgents – many of whom reportedly are originally from Mocimboa da Praia – earlier also briefly took control of the town in March 2020. At the same time, the town of Quissanga, approximately 180 km further south, then became the most targeted area in 2020, although the insurgents focused attacks on several other towns and districts. The insurgents further specifically targeted military and police forces, while the population in Cabo Delgado experienced horrific brutality in the form of killings, including beheadings, and other forms of violence that led to internal displacements and food shortages in the affected areas.[1]

What followed were harsh security responses from the Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique (Mozambican Defence and Security Forces) (FDS),[2] similar to indiscriminate responses elsewhere in conflict zones in Somalia, the Lake Chad Basin, the Sahel, and the Maghreb. The escalating attacks and heavy-handed responses have only heightened distrust among local residents and are alleged to have enhanced recruitment by the insurgents.[3] Currently, Cabo Delgado province is caught up in a security challenge with national, regional and international implications. The situation not only endangers the lives of tens of thousands of Mozambicans, but is also destabilising the upper north-eastern parts of Mozambique and certainly poses a threat to foreign direct investment pertaining to large-scale infrastructure, mining, exploration (especially natural gas), and other projects in Mozambique and the region.[4]

The Geopolitical Context

The conflict dynamics in Mozambique is playing out against the backdrop of a historically north–south divide in the country, which is rooted in the colonial history of Portuguese Mozambique. Pre-colonial and colonial Mozambique effectively developed as two separate entities, divided by the Zambezi River, until the first bridge over the river was constructed in 1934. Historically and pre-colonially, the south was ruled by successive large kingdoms, which based their economy on gold trade, while the north developed an economy largely based on cash-crop farming. Unlike the southern parts, the north-eastern parts – and especially the north-eastern coastal areas – were strongly influenced by the Swahili culture of east Africa and also home to a sizable Muslim population[5] linked to the historical Arab Muslim trade of several centuries between the Middle East and East African coastal communities.

Today, the different historical trajectories of the north and the south are still prevalent in the country’s geopolitical landscape. The capital city, Maputo, is located in the extreme south, while Pemba, the capital of conflict-ridden Cabo Delgado is located in the north-eastern parts and 1 666 km away from the capital city. The north–south divide was entrenched when the original colonial capital, Ilha de Moçambique in the Nampula province, was relocated to Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) in 1889. Since independence in 1975, the country’s top political leaders were mainly from the south, although the current president, Filipe Nyusi, is the first president with a northern background and originally from Cabo Delgado. The location of Maputo and the strong political focus on the south is, according to Vines, the ‘single most important cause of the imbalances in the social and economic development of Mozambique’.[6] This north–south divide is arguably the most important factor to consider in any understanding of the current conflict dynamics in Mozambique and will be under review in the sections that follow.

Areas of Limited Statehood

From the previous discussion, the question arises: which scholarly explanations help to understand or explain the conflict in north-eastern Mozambique? Researchers can certainly take more than one approach to study the insurgency, but this article argues that the scholarly notion of limited statehood, or specifically areas of limited statehood, is of particular significance and relevance to the case of Mozambique and the conflict in Cabo Delgado.[7]

In brief, areas of limited statehood are areas where the ability of the state in question to implement or enforce political decisions and/or to maintain a monopoly on the use of force is simply incomplete. Put differently, areas of limited statehood apply to countries and parts thereof where the central authority (or government) lacks the ability to implement rules and decisions. This means that the central authority falls short of exercising a legitimate monopoly over the means of violence, sometimes temporarily. Limited statehood further applies to a part or parts of a country, such as a province far away from the national capital, but can also pertain to policy implementation limitations, specifically an inability on the part of the central authority to enforce laws.[8]

In the Cabo Delgado province, the exercise of state authority is obviously problematic and a pressing political issue involving numerous governance challenges, not only at the national level, but also on a wider regional or trans-border level. After all, Mozambique clearly suffers from weak State institutions and is, therefore, a country that lacks strong and effective governance, largely due to a lack of institutional capacity and related gaps in legitimacy. Matsinhe and Valoistrikingly refer to the problem of authority or control in Mozambique as ‘half-mast sovereignty’.[9] In practical terms, Cabo Delgado is an area that the central government in Maputo in the south is unable to control or govern effectively. The central government is thus incapable of exercising its authority across the lengths and within the bounds of the country.

Implications of Limited Statehood

Limited statehood (or ‘half-mast sovereignty’) in Mozambique has a negative effect on the north-eastern parts in more than one way. First, the wellbeing of the population is badly affected. From a socioeconomic perspective, feelings of marginalisation and exclusion are prevalent in Cabo Delgado. The poorest health and sanitation facilities and the poorest schools are found in Cabo Delgado, while unemployment is rife, notably among youths. According to most social and economic indicators, this forgotten province fares very poorly, often ranking at the bottom of the Mozambican provinces.[10] In view of this, some observers argue that the conditions or roots of the insurgency and conflict in Cabo Delgo should be linked to endemic unemployment in the province, which became worse with the devastating effects of natural disasters in recent years.[11] Against this background, it is no coincidence that many members and supporters of Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah are socioeconomically marginalised young people, among whom a lack of proper education and formal employment has facilitated insurgent recruitment.[12]

Second, limited statehood applies to countries where state actors are not always visible and functional, and this results in non-state actors often moving into such spaces and becoming self-regulating private actors and even de facto governments or rulers.[13] In the case of Mozambique, limited statehood created opportunities for Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah as a non-state actor to enter the political landscape, which has resulted in many deaths, destruction of property and infrastructure, and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Mozambicans from Cabo Delgado. Although it is difficult to verify the death toll and number of human displacements in Cabo Delgado, reports indicate that insurgent attacks resulted in the deaths of about 1 500 locals towards the end of 2020, while about two million Mozambicans have been uprooted or negatively affected by the conflict dynamics.[14]

It could be argued that the Islamist insurgency in Cabo Delgado is driven by both international and domestic factors. Campbell rightly argues that Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah draws inspiration and legitimisation from international Islamist forces, which is evident in the fact that the movement has pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, with its ideal of establishing a caliphate. At the same time, the insurgency was unquestionably facilitated by issues related to limited statehood, specifically in relation to the domestic factors of marginalisation, neglect, exploitation, and government corruption.[15]

Weak Security Forces

As mentioned previously, limited statehood relates to countries where central authorities lack a legitimate monopoly over the means of violence. This is relevant in north-eastern Mozambique, where Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah attacked police and army installations. The FDS have experienced decades of neglect and the grave consequences of long-term underfunding, leaving them, especially the military, without the required capacity and competency to conduct operations that would sufficiently counter the threat posed by Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah. There are even reports of persistent leaks of information from inside the military by unmotivated soldiers on operational matters relating to logistics and conditions on the ground,[16] thus casting a shadow over the professionalism of the military.

The FDS – of which the special police forces, specifically the Rapid Intervention Unit and the Special Operations Group, have largely been deployed against the insurgents – are simply not up to the task of countering the insurgents on their own.[17] Until 2020, the Mozambican government thus increasingly relied on foreign security contractors,[18] mainly in the form of the South African-based Dyck Advisory Group and the Russian Wagner Group, to counter militant attacks. The inability of the FDS to protect communities in Cabo Delgado also coincided with reports of serious human rights violations in Cabo Delgado’s communities committed by the FDS,[19] casting a further shadow over the professionalism of both police and army officers.[20]

The use of mercenaries in support of the Mozambican armed forces has, however, not stopped attacks from Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah in north-eastern Mozambique. In fact, in November 2020, many locals were reportedly beheaded by the insurgents, which urged the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR), Michelle Bachelet, to appeal for urgent measures to protect civilians in what observers described as an increasingly dangerous and chaotic situation.[21] Appeals by various actors have also been made for intervention by the Southern African Development Community (SADC), specifically involving a multinational military force, as well as regional intelligence gathering and border management.[22] On 23 June 2021, a decision was made by SADC Heads of State and the government in Maputoto deploy a regional force to Cabo Delgado, while forces from Rwanda were deployed a few weeks prior to the arrival of the SADC force in July 2021.

Organised Crime Networks

The dilemma of limited statehood and related loss of control over parts of Mozambique is also linked to the prevalence of organised crime and criminal networks that are economically and politically entrenched in the Cabo Delgado region.[23]Cabo Delgado and nearby provinces have become a major conduit for the smuggling of drugs and other contraband. High-ranking figures in the ruling party, the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO), are reportedly involved, and drug cartels have profited from insecurity and instability in the province, even more so than the Islamist insurgents. Heroin trafficking has flourished in Cabo Delgado since the end of the Mozambican Civil War in 1974. In the past decade or even longer, many other illicit activities in the region, such as the smuggling of drugs, timber, ivory, rubies and other gemstones, and human trafficking, have also become commonplace.[24] These illicit activities play out in a political landscape where insecurity and violent extremism are the main markers in the absence of law enforcement and good governance.

It should be specifically noted that large volumes of heroin are produced in Afghanistan and then transported from there along international shipping routes to East and Southern Africa, including Mozambique. The bulk of these shipments are destined for western markets, but portions are also smuggled into Mozambique and South Africa.[25] Thus, the insurgency and related conflict dynamics in Cabo Delgado make law enforcement in the province and the policing of illicit activities even more challenging and complex.

As previously stated, neglect and a lack of funding have left the military without the capacity and competency to counter the threat posed by insurgents. From a coastal perspective, the Mozambican Navy is not in a position to prevent insurgents from entering the country by sea and plundering the districts along the coastal areas of the province.[26] Moreover, there are many allegations that elements of the State, including some police, are involved in illegal trafficking.[27] This supports the argument that corruption may be entrenched in the activities of the FRELIMO government.[28] Cabo Delgado is an important drug corridor in East Africa, especially since authorities in Tanzania and Kenya clamped down on trafficking networks in their territories, which effectively channelled the networks towards Mozambique. As such, there are numerous entry points into Mozambique and also many warehouses that link the producers to consumers.[29]

Conclusion

As a country of limited statehood, Mozambique suffers from weak State institutions, poor governance, and resultant insecurity. Cabo Delgado, as the most northern province, is an area that the central government in Maputo is unable to control or govern effectively. To put it differently, Cabo Delgado is under-governed, misgoverned, contested, and exploitable. Cabo Delgado is also a province where economic and related social exclusion exists with high unemployment as a main marker, notably youth unemployment. Cabo Delgado is thus often referred to as a ‘forgotten province’, one that that fares very poorly socioeconomically, and which is often ranked at the bottom of Mozambican provinces from a comparative perspective.

As explained previously, limited statehood applies to countries where state actors are not always visible and functional. This often results in non-state actors moving into political spaces and becoming the de facto rulers. In Cabo Delgado, where poverty and unemployment are prevalent, Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah has been able to recruit members and press forward as a non-state actor since 2017 and until it was capable of attacking the FDS. This was followed by acts of brutality against the local population in major parts of the province, the destruction of property, and displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah even gained the attention of the international community when it managed to capture and occupy the north-eastern strategic town of Mocimboa de Praia briefly.

There is little doubt that the Mozambican government lacks full control of the entire geographical territory that constitutes the country. The ability to control and govern fully is arguably a basic element of territorial sovereignty. This reality underlies the many challenges that have been outlined in this analysis, specifically Islamic militancy, a weak FDS and poor security responses to the militant threats, high levels of insecurity, and criminal networks. It also underlies the landscape of poverty, low socioeconomic development, and deprivation – conditions that facilitated Al Sunnah wa Jama’ah becoming a force in pursuit of a caliphate in a part of the country. Any long-term solution in north-eastern Mozambique will, among other things, have to address the problem of limited statehood and good governance, specifically relating to the imperative of controling the Mozambican territory fully and developing the required institutional capacity to rule and govern the entire country.

Dr Theo Neethling is a Professor in the Department of Political Studies and Governance at the University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa.

Endnotes

[1] Bukarti, Audu Bulama and Munasinghe, Sandun (2020) ‘The Mozambique Conflict and Deteriorating Security Situation’, Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, 19 June. Available at: https://institute.global/policy/mozambique-conflict-and-deteriorating-security-situation [Accessed 8 August 2020].

[2] Beula, Emídio (2021) ‘Armed Forces Begin to Gain Visibility in the Operational Command in Cabo Delgado’, Centro Para Democracia E Decenvolvimento, Guardião Da Democrcia, 10 January. Available at: https://cddmoz.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/NEW-APPROACH-TO-THE-CONFLICT_-Armed-Forces-begin-to-gain-visibility-in-the-operational-command-in-Cabo-Delgado.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2021].

[3] Pirio, Gregory; Pittelli, Robert; and Adam, Yussuf (2019) ‘The Many Drivers Enabling Violent Extremism in Northern Mozambique’, African Centre for Strategic Studies: Spotlight, 20 May. Available at: https://africacenter.org/spotlight/the-many-drivers-enabling-violent-extremism-in-northern-mozambique [Accessed 5 November 2020].

[4] Cilliers, Jakkie; Louw-Vaudran, Liesl; Walker, Timothy; Els, Willem; and Ewi, Martin (2021) ‘What Would it Take to Stabilise Cabo Delgado?’ ISS Today, 27 June. Available at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/what-would-it-take-to-stabilise-cabo-delgado [Accessed 17 January 2021].

[5] Vines, Alex (2020) ‘As Conflict in Cabo Delgado Increases, Will Frelimo Learn From its Mistakes?’ Mail & Guardian, 24 June. Available at: https://mg.co.za/africa/2020-06-24-as-conflict-in-cabo-delgado-increases-will-frelimo-learn-from-its-mistakes [Accessed 19 June 2020].

[6] Ibid.

[7] Börzel, Tanja; Risse, Thomas; and Draude, Anke (2018) The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood. Oxford: Oxford Handbooks Online. Available at: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198797203.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198797203-e-1 [Accessed 5 November 2020].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Matsinhe, David and Valoi, Estacio (2019) ‘The Genesis of Insurgency in Northern Mozambique’, ISS Southern Africa Report, 27, October, p. 16.

[10] Ibid, p. 12.

[11] Alden, Chris and Chichava, Sergio (2020) ‘Cabo Delgado and the Rise of Militant Islam: Another Niger Delta in the Making?’ SAAIA Policy Briefing, October. Available at: https://saiia.org.za/research/cabo-delgado-and-the-rise-of-militant-islam-another-niger-delta-in-the-making [Accessed 9 November 2020].

[12] Matsinhe, David and Valoi, Estacio (2019) op. cit., p. 13.

[13] Perera, Suda (2015) ‘Political Engagement with Non-State Actors in Areas of Limited Statehood’, The ‘State of the Art Paper’ Series, June. Available at: https://res.cloudinary.com/dlprog/image/upload/FEwXLX62TMIfCE4TmbVqRtti8ee1dG0F3ASmJYG7.pdf [Accessed 10 December 2020].

[14] ReliefWeb (2020) ‘Mozambique: Deteriorating Humanitarian Situation in Cabo Delgado Province’, Short Note, 8 April. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/mozambique-deteriorating-humanitarian-situation-cabo-delgado-province-short-note [Accessed 9 October 2020].

[15] Campbell, Rebecca (2020) ‘Maputo Refuses to Face Reality in Cabo Delgado, but SA Must Prepare for Conflict’, Engineering News, 11 December. Available at: https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/maputo-refuses-to-face-reality-in-cabo-delgado-but-south-africa-must-prepare-for-conflict-2020-12-11 [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[16] Alden, Chris and Chichava, Sergio (2020) op. cit.

[17] Beula, Emídio (2021) op. cit.

[18] Hamming, Tore Refslund (2021) ‘The Islamic State in Mozambique’, Lawfare, 24 January. Available at: https://www.lawfareblog.com/islamic-state-mozambique [Accessed 17 April 2021].

[19] Schlein, Lisa (2020) ‘Anarchy Reigns in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado as Conflict Escalates’, VOA News, 13 November. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/africa/anarchy-reigns-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-conflict-escalates [Accessed 18 November 2020].

[20] Bowker, Tom (2020) ‘Mozambique Accused of Abuses in its Fight Against Extremists’, AP News, 9 September. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/islamic-state-group-tanzania-africa-mozambique-crime-14b086ff3413bdb09802d12cc50aa3c8 [Accessed 5 April 2021].

[21] Ibid.

[22] Cilliers, Jakkie et al. (2021) op. cit.

[23] Centro para Democracie e Desenvolvimento (2020) ‘The Hidden Face of War in Cabo Delgado’, Maritime Security News, 4 August. Available at: https://maritimesecurity.news.blog/2020/08/05/the-hidden-face-of-the-war-in-cabo-delgado [Accessed 13 February 2021].

[24] Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (2020) ‘Are Mozambique’s Insurgents Closing in on Illicit Trafficking Profits?’ Daily Maverick, 8 May. Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2020-05-08-are-mozambiques-insurgents-closing-in-on-illicit-trafficking-profits [Accessed 15 November 2020].

[25] Haysom, Simone; Gastrow, Peter; and Shaw, Mark (2018) ‘The Heroin Coast. A Political Economy Along the Eastern African Seaboard’, ENACT Research Paper, 4, June. Available at: https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/2018-06-27-research-paper-heroin-coast-pdf.pdf [Accessed 18 July 2020].

[26] Centro para Democracie e Desenvolvimento (2020) op. cit.

[27] Pirio, Gregory et al. (2019) op. cit.

[28] Cilliers, Jakkie et al. (2021) op. cit.

[29] Centro para Democracie e Desenvolvimento (2020) op. cit.