Introduction

Internet shutdowns – and especially social media disruptions – in Africa are becoming more frequent, mostly around election times and during national exams. A significant communications shutdown occurred in Cameroon in 2018 and lasted 249 days, costing the country US$38 853 122.1 In 2016, an internet shutdown in India cost US$968 080 702.2 Data shows that globally, India leads, with 70% of all known large-scale shutdowns.3 In Africa, Cameroon leads, with 249 days in 2018.4 Some of the reasons cited by governments for shutting down the internet and communications includes national security, political events and school exams.

A communications shutdown entails cutting people off from the rest of the world, creating ambiguity and frustration and preventing access to information, which triggers strikes or protests that may become violent. This article examines two case studies – Kashmir and Cameroon – where recent communications shutdowns have led to violent conflict.

The information for Kashmir was collected qualitatively – that is, observation and interviews were the key tools used, during a visit to Kashmir in 2019. Ten key informant interviews were conducted with different stakeholders who were affected by the crisis. The interviewees worked in local hospitals or small businesses. In the case of Cameroon, a desk review was undertaken to understand and analyse the conflict. Information was also gleaned from non-governmental organisations working in Kashmir and Cameroon.

The communications shutdowns in Cameroon and Kashmir involved disrupting telephone, internet and mobile networks. These recent events in the two countries, which hampered people’s ability to communicate with each other and be informed, and which also included detention of people without trial, especially in Kashmir, violated Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This states: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reasons and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” Also, Article 9 states: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrests and detention,”5 and calls for the right of political prisoners to have access to justice and get fair trials, which was apparently not the case.

There is a close link between conflict, human rights and the denial of rights, as they can lead to the frustration of needs related to identity, welfare, freedom and security, which are fundamental rights for survival. If rights are denied, needs are frustrated – which can lead to violent conflict as people seek ways to address their basic needs and violated rights.6 Everyone has the fundamental right to express their opinion, as indicated by the United Nations (UN): “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”7

The Kashmir Context

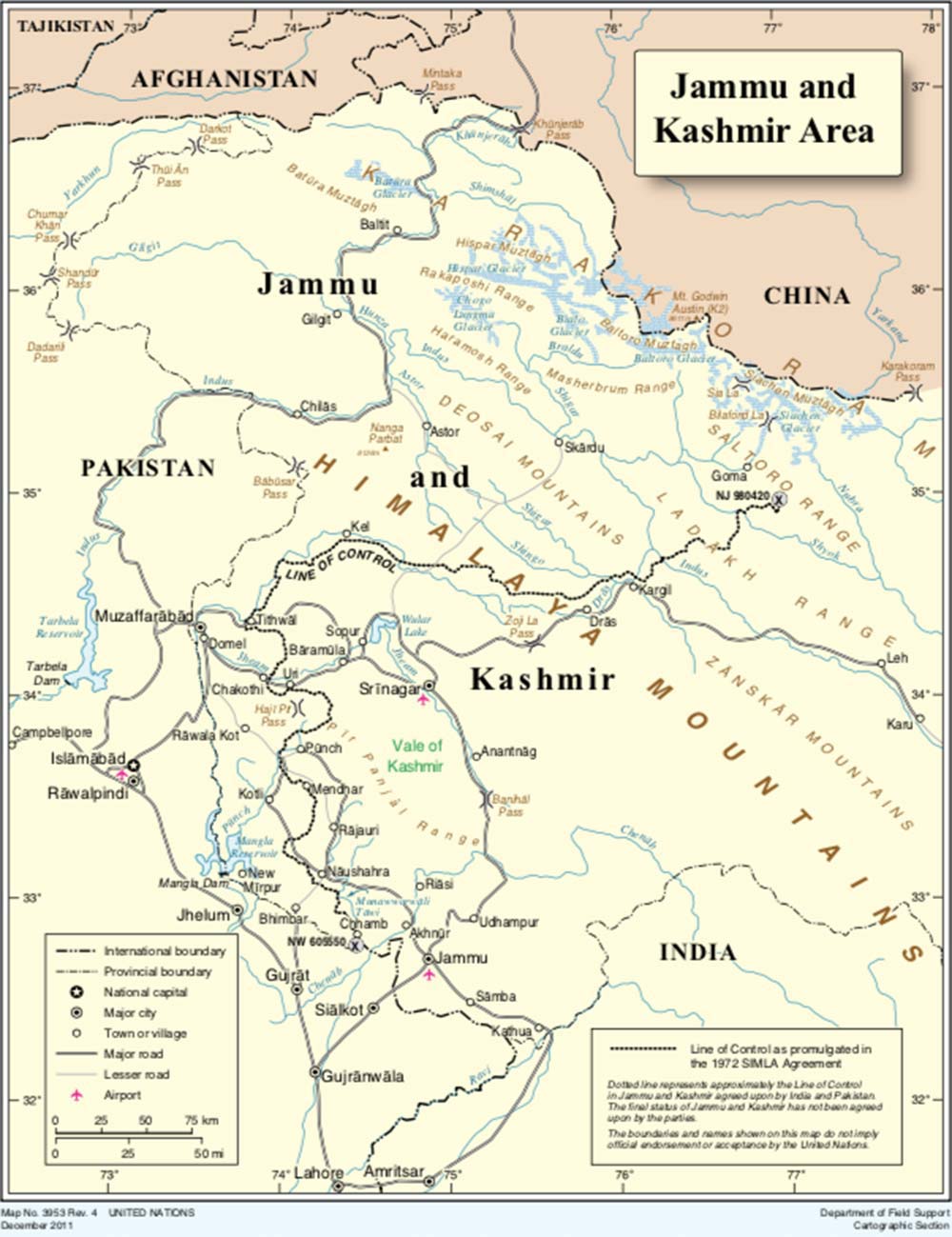

The Indian subcontinent in Asia has a population of 1.2 billion people and a total land area of 3 287 263 sq. km8 (including the disputed area of Kashmir). India is a very diverse country, with a large community of Hindus (80.5%). Hindi is the national language, spoken by 30% of the population.9

The Kashmir Valley lies within the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir in the north-eastern part of India, with the Line of Control (LoC) – that is, the border with Pakistan – along its northern and western borders. It covers a geographical area of 15 938 km, with a population of 6.9 million people, according to the Indian national population census of 2011.10

The state of Jammu and Kashmir has been the scene of a longstanding dispute between India, Pakistan, the Kashmiri population and, to a lesser extent, China since its accession to India on 26 October 1947.11 When Britain announced its plan to partition British India on 3 June 1947, it informed the princely states that Britain would not be able to recognise them as independent dominions, and expected them to ally with either India or Pakistan. Congress members informed Hari Singh, the Maharaja, that he should be ready to join either of the states. Given the fact that 77% of his subjects were Muslims, he would do well to entertain the wishes of his people of wanting to be with Muslim Pakistanis.12 At independence in 1949, the Maharaja had no agreement with either country and, in the following weeks, Pakistan exerted pressure on the Kashmir Valley to join Pakistan. This forced the Maharaja to ask for military support from India, which led to the Indian military occupation of the Valley.13 India sent troops to the Valley on 27 October 1947 to protect the Maharaja from any aggression from Pakistan.14 It is important to note that the state’s accession to India in 1947 was provisional. This understanding was formally acknowledged in the UN Security Council resolutions of 13 August 1948 and 5 January 1949. Both Pakistan and India agreed that accession would remain fully in force and could not be unilaterally discarded by either party until a referendum was held by the people. Since then, the Indian and Pakistani governments entrenched themselves in their positions and took a stand regarding the Kashmir issue and where it belongs. India’s position is that the entire Jammu and Kashmir was signed over to India, while Pakistan insists that a referendum should take place so that the people can decide whether they want to be part of India or Pakistan.

India and Pakistan have fought a number of wars, and India has clear military superiority over Pakistan. Pakistan also “donated” a part of Kashmir (the Korakoram Valley, which is part of Gilgit) to China, and China built a road between China and Pakistan.15 India fought a war with China and lost a large section of Ladakh.16 India also consolidated its position over Ladakh by integrating its territory into the Indian union. At this point, many Kashmiri youth chose violent recourse, and the militancy began.

In 1989, an armed insurgency started in the Kashmir Valley after local elections were allegedly rigged and the results were not accepted by most Kashmiri people. This armed struggle is explained differently, depending on whom you listen to. Most Kashmiris view it as a fight for freedom, India views it as a proxy war fought by Pakistan, Pakistan likes to portray it as a fight by Kashmiris to join Pakistan, and some extremist religious groups see it as part of the holy jihad for Islam. Since the early 2000s, the armed struggle has gradually evolved into a civil struggle. A ceasefire agreement along the LoC was signed in 2003 (however, it has been broken regularly) and, from 2008 onwards, the most commonly seen acts of resistance have been strikes – often called by the separatist leaders – and massive protest rallies by the general population.

On 4 August 2019, Article 370 (35A) of the Indian constitution, which gave Kashmir its special status, was scrapped in parliament. The state of Jammu and Kashmir was abolished in terms of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, and was divided into two union territories: Ladakh in the east and Jammu and Kashmir in the west. The people of Kashmir, in particular, fear that this was done to change the demographics of the state by making Muslims a minority group through eventually settling non-Kashmiris in the state.

It has been six months since August 2019 when the entire state was put under severe restrictions. At the time of writing, the Indian government made sure there was no access to internet and prepaid phones, including SMS, for all networks. The Indian government deployed an additional 150 000 troops in Kashmir before scrapping Article 370 of the Indian constitution that gave special autonomous status for the people of Jammu and Kashmir, to avoid incidents of violence and mass protests in the Valley. All communications means (mobile phones, internet, landlines, mail) have been suspended. The entire state remains completely cut off from the outside world, causing great despair to people, who are unable to contact their friends and family in, and outside, the state. All political leadership and their associates have been detained by house arrest or in hotels converted into prisons, most businesses and educational institutions are closed, and there is no public transport in operation. The Indian government claims that this is done to “keep the population safe” from being brainwashed by what it calls “anti-government militants”.

The Cameroon Context

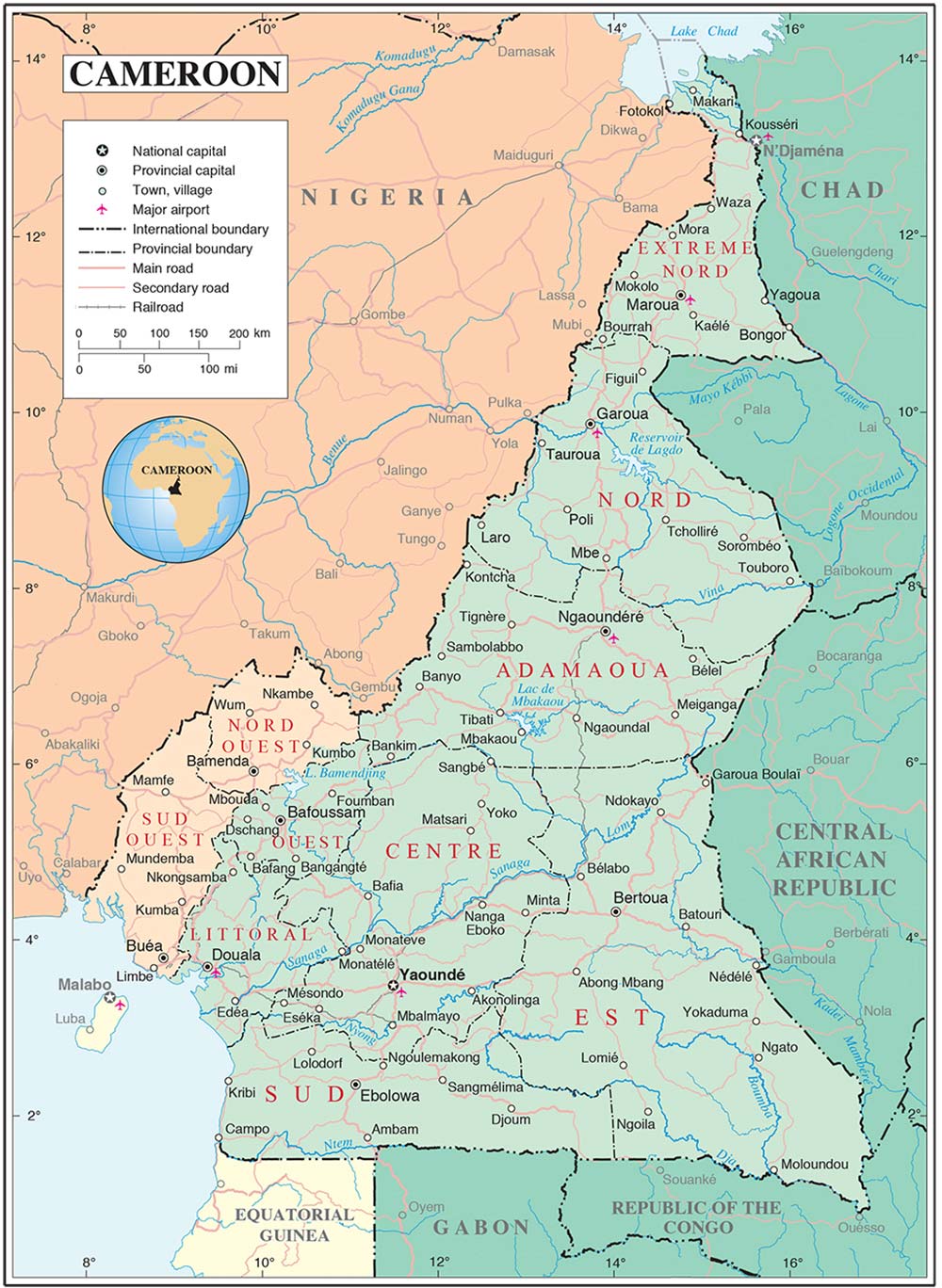

Cameroon, a coastal country located in Africa covering an area of 475 442 km, lies on the western side of Central Africa, on the Bight of Biafra, a bay on the eastern Atlantic Ocean. The country is bordered by Chad, Nigeria, the Central African Republic, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and Republic of the Congo. Cameroon’s 2019 population is estimated at 25.88 million citizens, with roughly 20% being anglophone.17

From 1884, Cameroon and parts of its neighbouring areas became the German colony of Kamerun, with the capital initially being Buea, and later Yaoundé. After World War II, this colony was partitioned between Britain and France under the 28 June 1919 League of Nations mandate. France gained the larger geographical area, transferring outlying regions to neighbouring French colonies, and ruled the rest from Yaoundé. Britain’s territory was a strip bordering Nigeria from the sea to Lake Chad, and was administered from Lagos.18

On 1 January 1960, French Cameroon gained independence and became La République du Cameroun (the Republic of Cameroon). The British-controlled southern Cameroon was then separated from Nigeria and was due to achieve full independence on 1 October 1961. However, the UN organised a referendum in which southern Cameroonians were asked to choose between joining the Republic of Cameroon or Nigeria. This vote was prompted by a British report that insisted its former territory would not survive economically on its own.

At this point, southern Cameroonians wanted nothing more to do with Nigeria. They had suffered enormously at the hands of the Igbo people, who had settled in their territory in previous decades. Therefore, they elected to unite in a new federation, becoming the Federal Republic of Cameroon. It was supposed to be a partnership of equals – a notion reinforced by bilateral negotiations that had started before the vote. These negotiations were concluded at the Foumban Conference in July 1961.19 The general view after the conference was that the delegation from the Republic of Cameroon, accompanied by French advisors, got virtually everything they wanted. The anglophones, who received none of the support promised by the British or the UN, felt sidelined.

As such, the new federation was born, but it was never a happy union. The region has been centrally governed, but neither of the two presidents since unification have been from the anglophone region – which led to the anglophones pushing for autonomy. This call was supported in a UN resolution, passed in April 1961, which defines the joining of the two former territories as a federation of two states, equal in status and autonomous.

Map of Cameroon showing the English-speaking area in the Northwest and Southwest regions20

The current tensions are between English-speaking Cameroonians and the government, dominated by French-speaking Cameroonians. The French-speaking government has ruled the country in an authoritarian way since the unification of the two former UN trusteeship territories in 1961.21 In 1972, the original federal structure, which was based on post-colonial unification, was abrogated. The English-speaking or Anglophone West Cameroon was annexed in a “United Republic”, and in 1984 the word “United” was scrapped. The country became Cameroon and the English-speaking region was assimilated into the French-speaking area. The statehood of the anglophones was slowly minimised – not by the French-speaking (francophone) community at large, but by the francophone-led and dominated government. This led to feelings of loss of identity and frustration among anglophone Cameroonians.

As frustrations grew, from 2016, protests became common in anglophone Cameroon. The youth took to the streets, and later, teachers and lawyers from the anglophone region demanded better treatment. Their discontent stemmed from the forced use of the French language, reduced opportunities for anglophone people and limited economic resources given to the anglophone region. It is important to note that the Cameroonian government provides all communication and documents only in the French language. French teachers with little English knowledge were sent to teach in anglophone schools, while French-educated civil law judges are sent to anglophone courts, which use the English common law system. Of the 36 ministers who are in charge of department budgets, only one is an anglophone.22 The budget allocated to the anglophone region is said to be disproportionally small. On 17 January 2017, the government ordered the suspension of internet services in the Northwest and Southwest anglophone regions of Cameroon following protests. Ironically, this was to avoid further protests and the spread of what they called “fake news”. The shutdown lasted 94 days and adversely affected the region’s 5 million residents. Since then, there have been further sporadic communications shutdowns, which have led to violent protests in the country.

Impact of Communications Shutdowns on Citizens

In Cameroon, the long period of internet blockage angered people and led to protests escalating into clashes with the police, during which at least four people were killed and many others injured.23 The internet blackout created “internet refugees”, as anglophone Cameroonians were forced to travel into francophone regions or Nigeria for internet access. “Silicon Mountain”, which is a nickname coined to represent the technology ecosystem (cluster) in the mountain area of Cameroon, was particularly crippled by the loss of internet. The blackout also adversely affected entrepreneurs, whose businesses collapsed as a result of the shutdown and they were unable to find work in the major French-speaking areas. After weeks of commuting from Buea to the commercial capital of Douala to access the internet, technology developers built an internet “refugee camp” in Bonako,24 a village near the tollgate separating anglophone Southwest from the francophone region of Littoral.

In Kashmir, the complete communications shutdown has also led to human suffering. It has impacted on everyone’s life in some way. Businesses, such as tourism (including the hotel industry), private hospitals, pharmacies and grocery shops have all been severely affected. An interview with hospital authorities in Srinagar confirmed that hospitals ran out of supplies due to the shutdown. Notably, because of its long history of conflict, Kashmir has high rates of mental health issues (45% of adults), according to a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Kashmir mental health survey in 2015.25 And a study by Action Aid in 2016 found that 58.69% of respondents have been exposed to traumatic experiences.26 In interviews conducted in several hospitals, psychiatrists reported a 50% increase in mental health patients, who are having difficulty coping with the situation during the shutdown. Doctors also reported cases of relapsing patients due to the recent happenings. One doctor said in an interview27 that due to the lack of cellular networks, medical teams at hospitals are facing difficulties in communicating with each other during medical emergencies.

Political leaders in Kashmir remain detained to ensure that there is no effective leadership to mobilise any potential response to the shutdown. Imams have been warned not to stray into politics or incite “the protesters”, with the threat of immediate arrest, and security forces have forbidden Muslim religious celebrations. There is an increased presence of Indian security forces around the mosques during times of prayer, particularly on Fridays, while both formal and informal gatherings are banned or monitored by security forces. Heavily armed checkpoints with razor wire, and random searches – both at checkpoints and other public areas – are commonplace and effective as a form of intimidation. People, particularly young men, are being randomly detained.

Shops and businesses remain closed, except for a short period in the morning or evening; schools remained closed in protest. In one interview,28 a participant explained: “The people are caught between the security forces, who want Kashmir to appear to be functioning normally, and the separatists/freedom fighters and the protestors, who want the shops to remain closed.”

At the time of writing, it was not clear what the Indian government planned to do to resolve the situation in the Kashmir Valley.

The Way Forward

The communications situation in Kashmir has not improved – the internet is still blocked in the Valley; landlines and post-paid phones are working, but not everyone can afford these lines. As a result, part of the population is still cut off from the rest of the world. In Cameroon, things have calmed down for some months, but the conflict is far from resolved. The tricky element of communications shutdowns is that they address the immediate need of governments to control information flow that could lead to protests and violence, which might be perceived as good on the one hand – but on the other hand, the lack of communication creates rumours and frustration, as most people start to depend on unverified information that could have further negative consequences. Thus, communications shutdowns are an ineffective way of controlling protests because the resultant anger and frustration further triggers conflicts, which can lead to escalated violence. Communications shutdowns seem to be a quick-fix solution for authorities in the short term, but in the long run, they are neither sustainable nor effective.

The communications shutdowns that led to conflict situations in Kashmir and Cameroon have different dynamics and need different responses. The Kashmir conflict is more complex, with both national and international dynamics. A single solution at one level will not work – there is need for multiple solutions at different levels. Organisations such as the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), with the support of the UN, could help resolve this conflict. The Cameroon case has regional dynamics affecting neighbouring countries. Therefore, regional organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), with support from the African Union (AU) peace and security component, could play a key role in resolving the conflict. Focusing on the Cameroon agreements that have not been respected – from the Foumban Conference to the UN’s resolution of 1961 regarding autonomy – the AU could act as a mediating party to ensure that these agreements are revisited and respected. The UN, as the custodian of these agreements, can also initiate forums to revisit these agreements.

Regional organisations can start by engaging the concerned governments and the leaders of the regions that are affected (anglophone Cameroon and Kashmir) in dialogue, as well as engaging community leaders at the grassroots level to understand the issues on the ground. Relaying information and experiences from people at the community level to the top levels of leadership is important. This could lead to meaningful dialogue and negotiations that include all relevant voices and stakeholders. Dialogue has unique and highly valuable properties. It can “strengthen relationships and trust, forge alliances, find truths that bind us together, and bring people into alignment on goals and strategies”.29 In other words, engagement through dialogue will provide an opportunity to people at different levels to have their voices heard. When people communicate, there is opportunity for feedback, interaction and relationship-building.

However, trust is not built overnight, and these conflicts have long histories that have affected many generations. Fostering trust will be a gradual process. In Kashmir, a major step in this direction can be gained by the government releasing all political leaders and youth who are in detention, and allowing them to access the justice system. The people of both Kashmir and Cameroon must be allowed to speak and express their feelings openly, without fear of being arrested and detained.

These communications shutdowns have created related conflicts that do not have quick-fix solutions because they are tied to other serious issues (marginalisation, exclusion of minority groups, inequality, underdevelopment, and so on). To fully address the needs of the people will not only be a matter of restoring communications. While people have suffered more directly recently as a result of the communications shutdowns, the governments of Cameroon and Kashmir must address all issues, including the root causes of these conflicts, such as identity group conflict. They must also address the generational trauma that has been caused by marginalisation. It is not in the interest of Yaoundé and New Delhi to keep silencing people. Instead, Cameroon and India need to open space for more communication and dialogue.

Endnotes

- CIPESA (n.d.) ‘A Framework for Calculating the Economic Impact of Internet Disruptions in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Available at: <www.cipesa.org> [Accessed 15 October 2019].

- Rajat, Kathuria, Mansi, Kedia, Gangesh, Varma, Kaushambi, Bagchi and Sekhani, Richa (2018) ‘The Anatomy of an Internet Blackout: Measuring the Economic Impact of Internet Shutdowns in India’, Available at: <https://icrier.org/publications/reports/> [Accessed on 17 October 2019], pp. 20–35.

- Rydzak, Jan (2016) Disconnected: A Human Rights-based Approach to Network Disruptions Impact. Global Network Initiative, p. 2.

- Access Now (2018) ‘The State of Internet Shutdowns Around the World Report: Data from the Shutdown Tracker Optimisation Project (STOP) 2016–2018’, #KeepItOn report, pp. 1–3, Available at: <https://www.accessnow.org/keepiton/> [Accessed 17 October 2019].

- United Nations General Assembly (1948) Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York: UN Press, pp. 3–4.

- Parlevliet, Michelle (2002) ‘Bridging the Divide: Exploring the Relationship between Human Rights and Conflict Management in Track 2’, pp. 8–43, Available at: <https://www.academia.edu/6027259/Bridging_the_Divide._Exploring_the_relationship_between_human_rights_and_conflict_management_2002> [Accessed 17 November 2019].

- UN General Assembly (1948) ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’, Article 19, Available at: <https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/> [Accessed 20 October 2019].

- Economist Intelligence Unit (2019) ‘India Country Report’, February, Available at: <www.eiu.com> [Accessed 6 September 2019].

- Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (2017) India Country Policy Paper. Médecins Sans Frontières, pp. 5–10.

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India (2011) ‘Provisional Population Tables: India: Census 2011’, Available at: <http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/prov_rep_tables.html> [Accessed 15 October 2019].

- Mattu, Abdul Majid (2002) The Kashmir Issues: A Historical Perspective. Srinagar: Ali Mohammad and Sons Publications, pp. v–vi.

- Jha, Prem Shankar (1996) Kashmir 1947: Rival Versions of History. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–10.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- This was a strategy used by Pakistan to gain diplomatic support from China. China is now a third party in the conflict, as it has part of Kashmir in its territory.

- This location in Ladakh remains strategically important for China as it connects Tibet and Xinjiang. The construction of this highway was one of the triggers for the Sino-Indian War of 1962.

- Worldmeters (2019) ‘Cameroon Population’, Available at: <https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/cameroon-population/> [Accessed 20 October 2019].

- US Department of State (2019) ‘Brief History of Cameroon’, Available at: <https://www.thoughtco.com/brief-history-of-cameroon-43616> [Accessed 15 November 2019].

- Achankeng, Fonkem (2015) The Foumban “Constitutional” Talks and Prior Intentions of Negotiating: A Historical Theoretical Analysis of a False Negotiation and the Ramifications for Political Developments in Cameroon. Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective, V. 9, article 11.

- The Economist (2017) ‘Cameroon Clamps Down on the Internet, and Anglophones’, map of Cameroon, Available at: <https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2017/03/09/cameroon-clamps-down-on-the-internet-and-anglophones> [Accessed 19 October 2019].

- Fanso, Verkijika G. (2017) ‘History Explains Why Cameroon is at War with Itself over Language and Culture’, Available at: <https://theconversation.com/history-explains-why-cameroon-is-at-war-with-itself-over-language-and-culture-85401> [Accessed 15 November 2019].

- Calis, Thijmen (2018) ‘Cameroon Shuts Down the Internet for 240 Days’, Available at: <https://techtribes.org/cameroon-shuts-down-the-internet-for-240-days/> [Accessed 20 November 2019].

- Ibid.

- Internet Sans Frontièrs (2017) ‘Submission to the UN Human Rights Committee on Concerns and Recommendations on Cameroon’, p. 5, Available at: <https://internetwithoutborders.org/> [Accessed 20 November 2019].

- Médecins Sans Frontières (2015) Kashmir Mental Health Survey. Médecins Sans Frontières, p. 9.

- Action Aid India, Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences Kashmir and Humanitarian and Civil protection (2016) Mental Health Illness in the Valley. A Community-based Prevalence Study of Mental Health Issues in Kashmir, pp. 10–12.

- Doctor in a hospital (2019) Interview with the author. Srinagar, India.

- Community leader (2019) Interview with the author. Srinagar, India.

- Paul Weller (2013) ‘The Dialogue Theories’, Available at: <www.DialogueSociety.org> [Accessed 8 December 2018].