Introduction

In late 2013, the Ebola virus was diagnosed in the forest region of Guinea. By mid-2014, it had spread alarmingly in the countries of the Mano River Basin – Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. By the time it was declared a global health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) in August 2014, at least 1 711 people were infected and 932 people had died from the virus.1 The Ebola virus was an alien phenomenon among both healthcare workers and ordinary people, and the affected countries lacked the capacity to respond effectively. The lack of proper response mechanisms at the beginning of the outbreak enabled the virus to spread rapidly, with a 90% fatality rate among the population, leaving citizens – mostly those in densely populated slum communities – in despair and desperation. What became further at risk was the stability of the three countries, two of which – Liberia and Sierra Leone – were still recovering from civil conflicts that had ended a decade earlier. While the crisis was largely health-based, it gravely affected political and security situations, leading observers to predict collapse, violence and a possible return to war.

Under what prevailing socio-economic conditions did the epidemic spread, and how did it pose political and security threats to the affected countries? How did the governments and their international partners respond to the crisis? How did the epidemic and response mechanisms lead to political and social tensions? With evidence from Liberia, this article explores these questions and advances some recommendations for promoting stability, with a focus on human security.

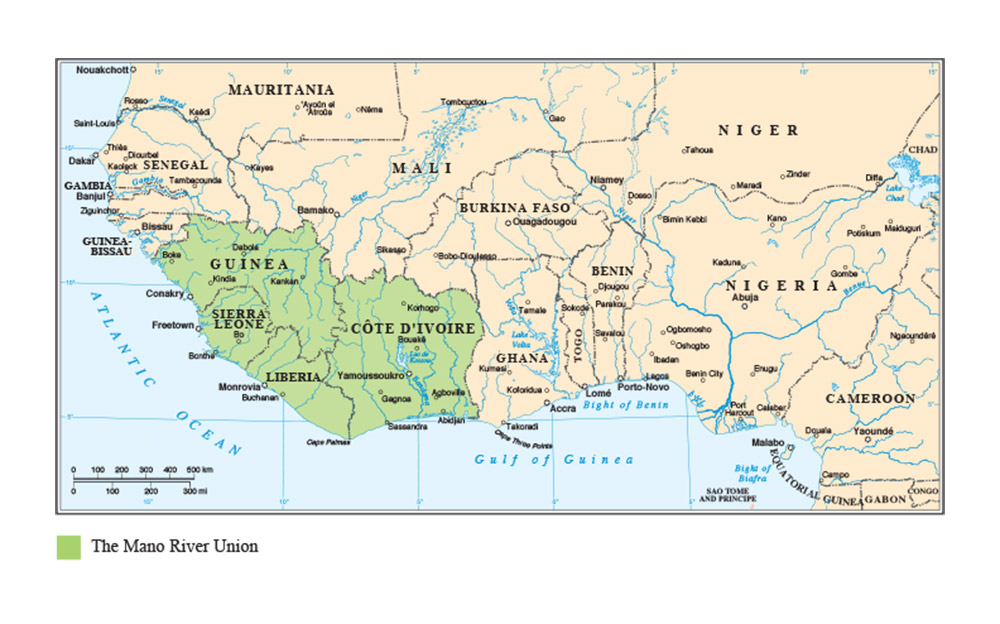

The Mano River Basin: A Region in Perpetual Fragility?

The countries in the Mano River Basin have been governed under mostly autocratic rule since independence. Strongman politics and one-party rule dominated the region and led to political uprisings and, ultimately, violent civil crises in the 1990s. Liberia and Sierra Leone experienced 14 years and 10 years respectively of wars, causing death, destruction of properties and mass displacements.2 In Guinea, strongman politics and military dictatorship led to continuous civil unrests and pockets of insurgencies. With the exit of Liberian president Charles Taylor in 2003, the countries in the region began transitioning from war to peace, with the aid of international organisations. The United Nations (UN) has kept a strong military and civil presence in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Côte d’Ivoire, which borders Liberia and Guinea, experienced instability and intermittent violent conflict during the same period. Both Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia currently have active UN missions facilitating peacebuilding.

At the time of the Ebola outbreak in 2013, all the countries in the Mano River Basin had reached some level of political stability, with no major outbreaks of violence for about 10 years and with democratic elections being held periodically to facilitate constitutional transitions of power. Liberia and Sierra Leone had two successful post-war elections, and Guinea held its first multiparty elections in 2010. The rise of civil society movements and massive international aid to support development programmes provided hope for building a sustainable democratic culture across the region and promoting socio-economic development. However, reports on these countries regarding human development, public integrity, corruption perception and fragility were appalling. In 2013, for example, Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone were at the bottom of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index, appearing in the category of Low Human Development. At the same time, Liberia and Sierra Leone were ranked among the countries with the highest poverty headcount percentages, based on the UNDP Multidimensional Poverty Index, at 85% and 77% respectively.3 In the same year, the three countries were declared among the world’s most fragile countries, with Liberia and Sierra Leone being put on alert, and Guinea on high alert.4 The countries in the region were perceived to be very corrupt, as shown by their respective scores in the Corruption Perception Index.5 Table 1 highlights the severity of the political and socio-economic conditions in the three countries at the time of the outbreak of the virus in 2013.

Table 1: Poverty, Corruption and State Fragility6

| Country | Human Development Index | Corruption Perception Index | Failed States Index |

| Liberia | 0.388 | 38 | 95.1 (alert) |

| Guinea | 0.355 | 24 | 101.3 (high alert) |

| Sierra Leone | 0.359 | 30 | 91.2 (alert) |

Massive poverty and weak state institutions – underpinned by official corruption and patronage politics – are symptoms of state fragility, and have been the case for a long time in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. No wonder, therefore, that the governments in these most-affected countries lacked the capacity to respond adequately to the epidemic and prevent its spread among the already-destitute population. But this lack of response speaks to the larger issue of the absence of state institutions in areas far from the capital city. The overly centralised governance systems in the region have not provided for effective and sustainable service delivery at a local level. It is the prevalence of such governance arrangements – in which local officials have to take orders from the capital city before acting – that rendered local officials and healthcare workers incapable of responding to the Ebola outbreak when it started in the rural areas of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The Human Toll of the Ebola Epidemic

The lack of adequate healthcare systems, particularly at local levels (rural areas), resulted in the Ebola virus spreading from a remote forest community in Guinea to densely populated urban communities in Liberia and Sierra Leone. In Liberia, fear of the virus led to the closure of regular health centres, compelling people mostly to self-treat. This likely led to more deaths from curable diseases such as malaria and typhoid fever, which are also prevalent in the country. Actual figures show that the active transmission of Ebola in the Mano River Basin in 2013–2015 resulted in more infections and deaths than the total death toll across all outbreaks since the virus was first discovered in Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire) in 1976.7 Liberia alone accounted for nearly half of the total deaths across the three countries. Table 2 shows the human toll of the epidemic in the three countries, as of September 2015.

Table 2: Human Toll of the Ebola Epidemic8

| Country | Cumulative Cases | Deaths |

| Liberia | 10 672 | 4 808 |

| Guinea | 3 805 | 2 533 |

| Sierra Leone | 13 911 | 3 955 |

| Total (Mano River Basin) | 28 388 | 11 296 |

How did the Governments Respond?

The rapid spread of the Ebola virus and the consequent death and chaos outweighed the capacity of the three governments to respond. By August 2014, the death rate had increased alarmingly and the population was frustrated. Hospitals were flooded with patients, health workers and medicines were in short supply, and health centres in Liberia rejected patients, while in Sierra Leone, strikes among healthcare workers worsened the situation. The population grew weary of the weak and inefficient response and retaliated in frustration – for example, in Guinea, villagers attacked and killed public health workers on allegations of spreading the virus. The governments resorted to security and political methods to contain the outbreak. A state of emergency was declared and all three countries closed their respective borders to prevent the movement of people, in an attempt to contain the Ebola virus. The International Crisis Group (ICG) warned that the spread of the virus and the military response by the three governments threatened stability, and could return the region to chaos.9 This claim was validated by the Liberian government when it declared that it no longer had the capacity to deal with the outbreak, warning further that the epidemic could lead to war in the country.10 Passionate pleas were made to the international community for assistance, which led to the United States (US), France and Britain setting up military hospitals and logistical support units in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone respectively. The military response by the governments in the affected countries exacerbated fear and panic among citizens – but, as the ICG suggested, the governments had more soldiers than doctors, thus they deployed their military strength, even though it was a health crisis. Like the governments in the affected countries, the three foreign powers responded through their militaries, in addition to other channels of support, to end the epidemic.

These responses heightened tensions between the sitting governments and opposition parties in Guinea and Sierra Leone, both of which were preparing for major elections. In Guinea, longstanding differences between the government and the opposition on scheduling local elections intensified when the government announced that it could only organise the presidential election in 2015 and that local elections would be postponed until 2016, due to the outbreak of the Ebola virus.11 In Sierra Leone, the national census – which is significantly linked to elections – was postponed, and opposition parties accused the government of the intent to extend its rule by postponing the general elections, using the Ebola epidemic as a cause célèbre.12 The Liberian government’s response to the outbreak led to mixed results. The evidence of security threats became even more conspicuous when measures such as night-time curfews and the heavy deployment of security forces at checkpoints were taken by government.

Ultimately, the mobilisation of communities by the government and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as key stakeholders in the fight against the virus became the most successful response mechanism to end the human-to-human transmission of the disease.

Political Instability and Insecurity in Liberia

The news of deployment of US military personnel in Liberia heightened fear in the population as rumours of coups and instability spread. Consequently, the Liberian government announced a curfew and restricted movements – including the quarantining of some communities suspected of harbouring Ebola patients. Those measures fell short of containing the spread of the virus effectively and stabilising the growing tensions. The postponement of the senate elections with the linked constitutional challenge, as well as the announcement of extra-emergency powers coupled with resistance in some communities, further exposed the fragile country to internal shocks. The reaction from the government, which led to political tension to the point of threatening stability in Liberia, is the focus of the following subsections.

Emergency Powers and Social and Political Tensions in Liberia

At the beginning of the outbreak of the Ebola virus, many Liberians denied the existence of the virus and accused the government of orchestrating a ploy to attract foreign aid. In their denial, people refused to comply with public health regulations, continued traditional burial rites and resorted to traditional healing methods. This is understandable in a country with a massive illiteracy rate, and with a history of broken trust between the state and its citizens. On 6 August 2014, a state of emergency was declared in Liberia, along with a night-time curfew. This gave the government the authority to enforce extra-constitutional measures. One of the casualties of these emergency powers was press freedom, marked by the arrest of journalists and the lock-down of a newspaper.13 West Point, a densely populated slum in the city of Monrovia, was quarantined when residents ransacked and looted an Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU), accusing the government of not consulting them and threatening their health by the establishment of the ETU. Local residents resisted the quarantine, and they were not allowed to protest due to the state of emergency. The government then enforced the quarantine by deploying armed security personnel and blocking all entries into the slum community. This was met by strong resistance from local residents, leading to clashes during which security forces fired live bullets, killing at least one teenager and wounding several others.

The use of emergency powers during the Ebola crisis was perceived by many as an attempt to suppress dissent from the opposition and civil society, many of whom criticised the government for managing the situation poorly and squandering international aid money intended to fight the epidemic. In October 2014, a request by the president to extend the state of emergency and to curtail certain fundamental rights was condemned by the opposition and the civil society movement, and subsequently rejected by the legislature. In response, the president issued Executive Order Number 65, banning mass movements of people, particularly in relation to the senate elections campaign. According to the government, the objective of the executive order was “to strengthen the efforts of the Government of Liberia to contain the spread of Ebola, protect the security of the State, maintain law and order, and promote peace and stability in the country”.14

This brought to the fore important questions on the use of emergency powers in crisis situations in Liberia. The Constitution of Liberia provides in Article 86(b) that “[a] state of emergency may be declared only where there is a threat or outbreak of war or where there is civil unrest affecting the existence, security or well-being of the Republic amounting to a clear and present danger”. The key issues during the contention between the government and the opposition were the curtailment of fundamental rights such as free movement and free expression, and freedom of association and religion. Many thought these were excessive and untenable in relation to the fight against Ebola.

Constitutional Crisis on Senate Elections

Senate elections, set to be held on 14 October 2014 in line with the constitution, could not be held in Liberia due to the state of emergency put in place to contain the spread of the Ebola virus. All election-related activities – including mass rallies and queuing to vote – were against the public health measures needed to stop the human-to-human transmission of the virus. With a marked decrease in the number of Ebola cases by November 2014, stakeholders – including the National Election Commission (NEC), political parties and civil society organisations – held consultations and rescheduled the elections for 16 December 2014. However, some political actors challenged the constitutionality of this move in the Supreme Court, which led to a stay order. Their contention was that since the date set by the constitution for the elections had passed without the elections being held, no institution (not even the government) had the authority to set a date for elections under the constitution; thus, they demanded what they called a “sovereign national conference” of the citizens.15 The Supreme Court subsequently ruled in favour of the NEC, and the senate elections were finally held on 20 December 2014.

Liberia was headed for an unprecedented constitutional crisis if the senate elections were not held before the constitutional tenure of the incumbent senators expired in January 2015. Considering the mounting political and social tensions during the height of the epidemic – occasioned by street protests, excessive use of force by security forces and bickering among politicians – it could easily be predicted that this could have led to prolonged political instability, if not a violent crisis, in Liberia.

Conclusion

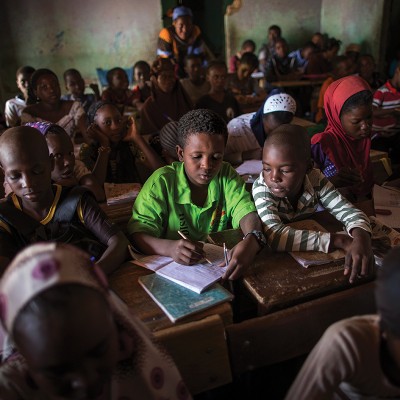

The Ebola epidemic of 2013–2015 has been the most devastating tragedy to have hit the three countries of the Mano River Basin since the civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone. As mentioned, the disease not only infected and killed people in the Mano River Basin, but had the greater impact of affecting peace and stability in the subregion, as was seen in Liberia. Both the Ebola epidemic and the attendant political crises are symptomatic of continued state fragility and weak capacity in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. Billions of dollars of aid money have been spent in the name of supporting state-building in the three countries for over a decade. Unfortunately, the Ebola epidemic revealed that the massive investment of international aid money and national expenditures from government budgets have done little to support functional state institutions. With a focus on physical security – police and military – the international community and the national governments paid little attention to human security issues such as investing in healthcare, education and youth empowerment, in the last decade of peacebuilding in the region.

The Liberian experience of the Ebola epidemic is highly illustrative of the inability of the states in the region to deliver on their constitutional promises and to maintain political and social stability while responding to non-military or non-security threats. Post-Ebola recovery measures in the subregion must pay keen attention to key sectors of the state and society. Practical actions are needed beyond the promises of economic growth and development through the much-vaunted models of “trigger-down” economic policies that restrict governments to certain policies.

Liberia, the hardest hit of the three affected countries, has the opportunity to recreate itself through its ongoing constitutional reform exercise. It is important that its current reform focuses on building a democratic and decentralised governance system with emphasis on devolving authorities and resources for local service delivery capacity, particularly in the social service sector: health, education and youth empowerment. While post-Ebola recovery efforts in Liberia need to focus more on improving the ravaged healthcare sector, democratic reforms to ensure political and financial accountability of state actors are critical to strengthen the capacity of the Liberian state in all areas, particularly in delivering basic social services and human security, which has received very little attention over the years of peacebuilding and state-building.

Endnotes

- Kelland, Kate (2014) ‘WHO Declares Ebola Epidemic as an International Health Emergency’, Available at: <http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/08/08/us-health-ebola-emergency-idUSKBN0G80M620140808> Accessed 21 September 2015.

- It has been reported that over 250 000 people were killed in Liberia and 70 000 in Sierra Leone. See Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Liberia (2009), Available at: <http://trcofliberia.org/reports/final-report> Accessed September 2015; See also Kaldor, Mary and Vincent, James (2006) Evaluation of UNDP Assistance to Conflict-affected States; Case Study Sierra Leone. New York: UNDP Evaluation Office.

- United Nations Development Programme (2013) The Rise of the Global South: Human Development Report 2013. New York: UNDP.

- Fund for Peace (2013) ‘Failed States Index 2013’, Available at: <http://library.fundforpeace.org/library/cfsir1306-failedstatesindex2013-06l.pdf> Accessed 25 September 2015.

- Transparency International (2013) ‘Corruption Perception Index 2013’, Available at: <https://www.transparency.org/cpi2013/results> Accessed 25 September 2015.

- The author assembled this table with data from the Human Development Report 2013 Available at: <http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/14/hdr2013_en_complete.pdf> Accessed 25 September 2015 , Corruption Perceptions Index 2013 Available at: <http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-Transparency-International-Corruption-Perceptions-Index-2013/$FILE/EY-Transparency-International-Corruption-Perceptions-Index-2013.pdf> Accessed 25 September 2015, and Failed States Index 2013 Available at: <http://library.fundforpeace.org/library/cfsir1306-failedstatesindex2013-06l.pdf.> Accessed 25 September 2015.

- Author unknown (2014) ‘Ebola: Mapping the Outbreak’, BBC News, 14 January, Available at: <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-28755033> Accessed 31 May 2016.

- The author assembled this table from data from World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) ‘Ebola Data and Statistics: Situation Summary, Data Published on 30 September’, Available at: <http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.ebola-sitrep.ebola-summary-20150930?lang=en> Accessed 20 September 2015.

- International Crisis Group (2014) ‘Statement on Ebola and Conflict in West Africa’, Available at: <http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/publication-type/media-releases/2014/africa/statement-on-ebola-and-conflict-in-west-africa.aspx> Accessed 21 September 2015.

- Author unknown (2014) ‘Liberia Fears Ebola Crisis will Spark War’, Al Jazeera News, 24 September, Available at: <http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2014/09/ebola-liberia-war-201492485447852773.html> Accessed 27 September 2015.

- Camara, Karim (2015) ‘Political Tensions in Guinea Heating Up’, Voice of America, 22 April, Available at: <http://www.voanews.com/content/political-tensions-in-guinea-heat-up/2730184.html> Accessed 1 October 2015.

- Author unknown (2015) ‘Sierra Leone News: SLPP Insists on Elections to be Held as Expected’, Awoko, 26 May, Available at: <http://awoko.org/2015/05/26/sierra-leone-news-slpp-insists-on-elections-to-be-held-as-expected> Accessed 1 October 2015.

- On 14 August 2014, officers of the Liberia National Police forcibly entered the offices of the National Chronicle newspaper, arrested and detained two journalists and shut down the paper. The publisher resisted arrest. See Center for Media Studies & Peace Building (CEMESP) (2014) ‘Liberia: Offices of Independent Newspaper Shut Down, Staff Arbitrarily Arrested’, Ifex, 18 August, Available at: <https://www.ifex.org/liberia/2014/08/18/shutdown_arrest> Accessed 31 May 2015.

- Executive Mansion (2014) ‘President Sirleaf Issues Executive Order No. 65; Prohibits Mass Movements of People Including Rallies, Parades and Demonstrations’, Press Release, 4 December, Available at: http://www.emansion.gov.lr/2press.php?news_id=3151&related=7&pg=sp#sthash.9MlrmUbs.dpuf Accessed 3 October 2015.

- For a deeper analysis of this constitutional crisis, see Nyei, Ibrahim Al-bakri (2014) ‘Election or No Election: Another Hard Test for the Liberian Constitution’, Available at: <http://www.ibrahimnyei.blogspot.com/2014/12/election-or-no-election-another-hard.html> Accessed 4 October 2015.