Introduction

Insecurity in Nigeria is a recurring phenomenon that threatens the well-being of its citizens. The multipronged occurrence constitutes a bane to development and leads to the proliferation of crime. As a multifaceted quandary, insecurity assumes varying dimensions in different geopolitical zones. The South West is plagued by a surge in cybercrime, armed robbery, kidnapping, domestic crime, extrajudicial killings, herder-farmer conflicts, ritual killings, and banditry. The South East is a haven for ritual killings, commercial crime, secessionist agitation, kidnapping, herder-farmer clashes, attacks by unknown gunmen, and banditry. The South remains threatened by militancy, kidnapping, and environmental agitation. The North East has been subject to a humanitarian crisis lasting over a decade and caused by the Boko Haram insurgency and the Islamic State in West Africa Province. Meanwhile, the North West is enmeshed in illegal mining, ethnoreligious killings, and banditry. It is, therefore, an axiom that insecurity in Nigeria has assumed a disproportionate geopolitical stance and that it has claimed thousands of lives and extensive damage and loss of property.

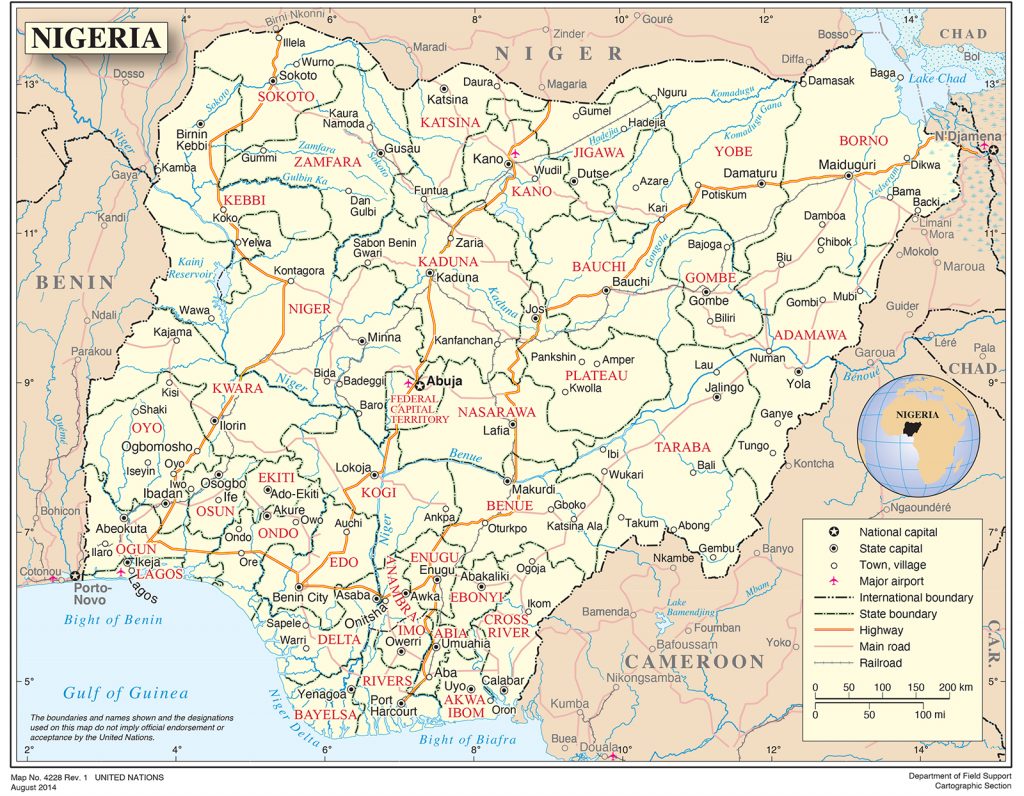

In the context of the aforementioned security problems, banditry has recently come to the fore with increased activities in the northwest region of the country, particularly in Zamfara, Kaduna, Niger, Sokoto, Kebbi, and Katsina states. Banditry refers to ‘a type of organized crime that includes kidnapping, armed robbery, murder, rape, cattle-rustling, and the exploitation of environmental resources’.[1] Some of the factors that have led to the rise and persistence of banditry in Nigeria are under-governed spaces, a weak security apparatus, the proliferation of small arms and light weapons, socioeconomic conditions such as poverty and unemployment, cattle rustling, and illegal mining activities in the North West.

Even though the incidence of banditry in Nigeria is beginning to attract scholarship, the theoretical expositions remain embryonic. This article fills the gap by offering explanations for the occurrence of banditry in Nigeria through Situational Action Theory (SAT). This is done bearing in mind that an understanding of the motivating factors of crime provides insights and potential solutions. Furthermore, the available literature largely fails to characterise the phenomenon adequately and tends to offer vague solutions. The article thus proposes practical solutions through the strategies of Situational Crime Prevention (SCP). The article presents an overview of banditry in Nigeria and SAT, as well as discussing mitigating the challenge of banditry through SCP.

An Overview of Banditry in Nigeria

Banditry is a serious crime that poses a security challenge to democratic governance and peaceful coexistence in Nigeria. Bandits often terrorise communities in the North West region. Their activities include kidnapping, arson, shooting, rape, cattle rustling, killing, and looting.[2]

The prevalence of under-governed spaces where the government’s control is ineffective and limited is a major factor giving rise to banditry.[3] Such areas are characterised by bad governance, weak legitimacy, protracted conflict, and poor leadership, which makes citizens vulnerable to exploitation by terrorist groups, traffickers, and other criminal elements. Such areas are not generally entirely devoid of the government’s control but are governed poorly and differently from larger communities. These poorly governed territories are plagued by bandits and other criminal gangs due to their remoteness, which allows for the perpetuation of an array of illegal business activities. It is not uncommon to find human trafficking, piracy, cattle rustling, and illegal mining in such areas. These areas are used to promote and sustain an illegal, informal economy. Examples of such include large forests in Rumah/Kukar Jangarai, Kamuku, Balmo, Katsina, Kaduna, Bauchi, and Kano states. Meanwhile, the Nigerian police are generally understaffed and poorly equipped, leaving them incapable of promoting security in under-governed spaces, a major factor that encourages criminality in these areas.

Under-governed spaces coupled with the country’s porous borders have increased the influx of small arms and light weapons from the Sahel region – thus increasing the opportunities for crime. This is facilitated by vast forests which allow the illegal arms trade to fester. It is further complicated by the socioeconomic conditions prevalent in the North West, which leave the youth vulnerable to recruitment for criminal activities. The socioeconomic realities that exist include multidimensional poverty, widespread unemployment, deprivation, inequality, marginalisation, exclusion and lack of access to basic amenities. Even though this is a national challenge, the North is particularly affected. For example, Zamfara, Jigawa, and Sokoto states have poverty levels of 74%, 87%, and 87.7%, respectively.[4] These conditions make the region even more susceptible to crime, including as a result of the activities of Boko Haram and now, banditry.

Another major factor that has increased the incidence of banditry is the complex relationship between pastoralists and farmers. Desertification, drought, climate change, cattle rustling, insurgency, and population growth have led to the ongoing migration of pastoralists or herdsmen. This migration has seen pastoralists clash with farmers over the encroachment of farmland and destruction of crops. In extreme cases, these conflicts have led to the wanton destruction of life and property of both the farmers and pastoralists, thus contributing in no small degree to the level of insecurity in the country.[5]

Another cause of banditry in Nigeria is the illegal mining activities in the North West region of the country. Illegal mining is prominent in Niger, Kebbi, Katsina and Zamfara states, has triggered violent conflict over the control of minefields, and has led to the deaths of thousands of people.[6] Due to the displacement caused by the conflict, the people of the region engage in banditry as an alternate means of survival.[7] Meanwhile, the increase in illegal activities has been attributed to poor governance, poor service delivery, the prevalence of poverty, and widespread unemployment in the geopolitical zone, which makes the youth susceptible to involvement in crime.

The effect of banditry is extensive. In addition to complicating the security crisis in the country, it has also increased the incidence of forced migration, food insecurity, cattle rustling, destruction of property, health challenges, displacement, humanitarian crises, and death. For example, between 2018 and 2020, an estimated 4900 people lost their lives to bandit attacks, while 309 000 internally displaced persons and 60 000 refugees have been recorded.[8]

Situational Action Theory and Banditry in Nigeria

SAT is a theory of crime developed in 2004 by Per-Olof Wikström. It attempts to explain what moves people to action such as crime by incorporating ecological, criminological, sociological, and behavioural sciences. Crime is an action that violates the law and is a result of the interplay between an individual’s exposure to criminogenic settings and the propensity for criminality, that is, an individual’s time in an unsupervised or poorly governed space and level of self-control determine the occurrence of crime. SAT posits that crime is motivated by an individual’s morality and the prevailing situation. People are responsible for their actions, but the causes of their actions are situational. Therefore, an act of crime is the product of a choice made after considering various alternative scenarios and stimuli presented by a particular situation. Thus, crime is committed when it is perceived as a worthwhile and suitable alternative, given the prevailing situation, and/or when a person fails to apply moral restraint.[9]

The situational stance advanced by SAT rests on four major elements: the person (psychological make-up, experience, and so on), the setting (the environment an individual is exposed to), the situation (choices resulting from interaction with the setting), and action (the person’s behaviour). SAT explicates the notion that factors that induce crime are the same for all people, regardless of their age and criminal career stage. The theory argues that people’s propensity to commit a crime is different, just as environments also vary. The setting an individual finds themself in determines whether a crime will be committed or not. For example, an individual who struggles as a result of multidimensional poverty and finds themself in an environment without guardianship, but with certain escape options and resources, is likely to commit crime. Crime occurrence, therefore, is the interaction between an individual’s crime propensity and the setting’s criminogenic incentive. A person with a low crime propensity – due to a strong moral rectitude and/or the presence of government authority – will be less susceptible to criminogenic incentives, while a person with a high crime propensity is less likely to resist crime inducement.[10]

SAT proposes the following key basic assumptions:

- People are essentially rule-guided creatures. They express their desires and respond to friction within the context of rule-guided choices;

- Social order is based on shared rules of conduct. Patterns in human behaviour are based on rule-guided routines;

- People are the source of their actions. People perceive, choose, and execute their actions;

- The causes of action are situational. An individual’s particular perception of action alternatives, the process of choice, and execution of the action are triggered and guided by the relevant input from the person-environment interaction;

- Crimes are moral actions. Crimes are actions that break rules of conduct (stated in law) about what is the right or wrong thing to do in a particular circumstance.[11]

SAT explains different crimes ranging from theft to terrorism. In explaining radicalisation and terror, SAT highlights the key problems of vulnerability, exposure, and emergence. To develop crime propensity, the individual has to be exposed to crime-supportive moral contexts; a setting that induces crime must be present and the person in regular contact with it; and the individual has to be sensitive to the influence of the crime-supportive setting that they come into contact with.[12]

When applied to banditry in Nigeria, SAT expounds on the interaction between the person, setting, situation, and action. The individual (especially with a low crime propensity) is motivated by the situation to consider crime as a worthwhile alternate to realise the desired outcome. Because the individual is a product of the society they live in, they are likely to subscribe to society’s norms. Following Wikström’s postulations, crime results from an interaction between a person and the environment.[13] Therefore, in a society characterised by criminogenic inducement, the individual becomes vulnerable to crime. The situation and settings thus motivate an individual’s action. The psychological experience resulting from multidimensional poverty, exclusion, unemployment, marginalisation, inequality, and displacement coupled with the prevailing circumstance in the setting, such as under-governed spaces, illegal mining activities, the influx of small arms and light weapons and a poorly equipped security apparatus, engenders a negative situation which encourages deleterious action (banditry). Put differently, the increase in banditry in Nigeria is attributable to the interactions among people who are victims of adverse socioeconomic conditions in the setting. The setting is characterised by recurring social malaise. Negative choices result from interaction with the setting, which leads to criminal action.

Mitigating the Challenge of Banditry through Situational Crime Prevention

As SAT argues, to change people’s criminal behaviour, we must change people, change environments, and change people’s exposure to environments. This will help reduce crime propensity and external criminogenic incitement and interaction. SCP is applicable in addressing situations that increase the propensity for crime. SCP was developed by Ronald Victor Clarke in the 1970s as a means to reduce the opportunity for crime in an action setting by carefully manipulating the situational factors that engender crime.[14] It calls for the elimination of situational opportunities that motivate crime through intervention. Appropriate strategies to remove crime opportunities and prevent crime can thus be devised. The SCP model includes five strategies incorporating 25 techniques for crime reduction. This intervention strategy involves making crime less likely by deterring offenders and/or reducing situational actions that motivate crime.[15] The situational prevention technique includes:

- Increasing the effort;

- Increasing the risks;

- Reducing the rewards;

- Reducing provocation; and

- Removing excuses.[16]

This model is relevant in addressing banditry in Nigeria. It stresses the need to remove the situational factors that warrant crime, such as poorly governed spaces, transhumance, the proliferation of arms, illegal mining activities, and other poor socioeconomic conditions. To adequately prevent banditry will require increasing anti-crime efforts. This includes making the target more difficult to exploit by encouraging community policing; managing access to facilities through controlling transhumance activities; deflecting offenders by reducing the porousness of borders; and controlling tools or weapons by reducing the proliferation of small arms and light weapons, as well as implementing laws to punish illicit arms dealers.

Another technique presented by SCP is to increase the risk for offenders when committing a crime. To achieve this, emphasis should be placed on extending guardianship through increased government presence in vast under-governed spaces; assisting natural surveillance through improved security; and reducing anonymity through identifying offenders and sponsors of banditry. SCP also proposes the use of messaging that communicates the government’s intolerance for crime and reward for community vigilance. This should be accompanied by the strengthening of formal surveillance, for example, through the deployment of forest guards and the use of drones to monitor activities in forests.

SCP further suggests the reduction of rewards that motivate crime. This involves discouraging illicit gold mining; converting the vast forests for government use; identifying property, for example, by branding cattle to reduce cattle rustling; disrupting markets by monitoring illicit trade hotspots; and denying benefits by desisting from paying ransoms to bandits for the release of kidnapping victims.

Provocation must also be reduced. This involves the reduction of frustration through policies that reduce poverty, marginalisation and unemployment; the control of violent attacks and management of disputes, particularly between pastoralists and farmers; discouraging imitation by arresting and prosecuting offenders; and responding swiftly to distress calls.

SCP also advocates for the removal of excuses for crime by implementing reasonable measures, such as granting licenses for mining activities; appealing to individuals’ conscience through messages such as ‘crime does not pay’; and discouraging drug abuse among youths.

Conclusion

The incidence of banditry in Nigeria is a growing phenomenon that gravely threatens human security. It is prevalent in the North West geopolitical region of the country but has the potential to expand into transnational crime. Thus, it is imperative to pay close attention to the threat. This article presented the theoretical underpinnings of SAT and SCP in relation to this threat. It established that banditry is a situational crime necessitated by the interplay of the person, setting, situation, and action. As such, banditry in Nigeria is sustained by the interaction between a person’s experience and prevailing economic realities, such as poverty and unemployment (environment or setting). It is encouraged by a weak security apparatus in large under-governed spaces, which is part of the setting, and characterised by illegal mining and cattle rustling (action).As banditry is conceived of as a situational crime, a situational solution is proposed. SCP emphasises changing the criminogenic setting that necessitates crime and reducing the situational factors for crime propensity. The government should adopt social risk management techniques to reduce poverty and vulnerability, particularly in the North. The government should also reform the security apparatus with an emphasis on increasing the size, funding, training, intelligence, support, and communication equipment of security forces. It is also recommended that the government establish its presence and make use of effective leadership in poorly governed spaces in the country. This will reduce the situational factors that compel crime and encourage the adoption of a situation-based prevention strategy.

Tope Shola Akinyetun teaches Political Science at Adeniran Ogunsanya College of Education, Lagos State, Nigeria.

Endnotes

[1] Brenner, Clair (2021) ‘Combating Banditry in Northwest Nigeria’, Available at: <https://www.americansecurityproject.org/combating-banditry-in-northwest-nigeria> [Accessed 29 July 2021].

[2] ACAPS (2020) ‘Nigeria: Banditry and Displacement in the Northwest’, Available at: <https://www.acaps.org/sites/acaps/files/products/files/20200723_acaps_short_note_northwest_banditry_crisis_nwbc_nigeria.pdf> [Accessed 23 July 2021].

[3] Ojo, John Sunday (2020) ‘Governing “Ungoverned Spaces” in the Foliage of Conspiracy: Toward (Re)Ordering Terrorism, from Boko Haram Insurgency, Fulani Militancy to Banditry in Northern Nigeria’, African Security, 13(1), 77–110.

[4] Abdulrasheed, Abdulyakeen (2020) ‘Armed Banditry and Human Security in North Western Nigeria: The Impacts and the Way Forward’, Journal of Humanities Social and Management Sciences, 1(1), 89–107.

[5] Uche, Jasper and Iwuamadi, Chijioke (2018) ‘Nigeria: Rural Banditry and Community Resilience in the Nimbo Community’, Conflict Studies Quarterly, 24, 71–82.

[6] International Crisis Group (2020) ‘Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem’, Available at: <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/288-violence-in-nigerias-north-west.pdf> [Accessed 24 July 2021].

[7] Ogbonnaya, Maurice (2020) ‘How Illegal Mining is Driving Local Conflicts in Nigeria’, Institute for Security Studies, Available at: <https://issafrica.org/iss-today/how-illegal-mining-is-driving-local-conflicts-in-nigeria> [Accessed 28 July 2021].

[8] ACAPS (2020) op. cit.

[9] Wikström, Per-Olof (2019) ‘Explaining Crime and Criminal Careers: The DEA Model of Situational Action Theory’, Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 6, 188–203.

[10] Ibid, p. 193.

[11] Centre for Analytic Criminology (2019) ‘Situational Action Theory (SAT)’, Available at: <https://www.cac.crim.cam.ac.uk/resou/sat> [Accessed 30 July 2021].

[12] Bouhana, Noémie and Wikström, Per-Olof (2011). Al-Qa’ida-Influenced Radicalisation: A Rapid Evidence Assessment Guided by Situational Action Theory. London: UK Home Office, pp. 21–22.

[13] Wikström, Per-Olof (2019) op. cit.

[14] Clarke, Ronald Victor (2005) ‘Seven Misconceptions of Situational Crime Prevention’, In Tilley, Nick (ed.), Handbook of Crime Prevention and Community Safety. Abingdon: Routledge, p. 39.

[15] Freilich, Joshua and Newman, Graeme (2017) ‘Situational Crime Prevention’, Available at: <https://oxfordre.com/criminology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264079-e-3> [Accessed 27 July 2021].

[16] Ibid, p. 8–9.