Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) ‘refers to mining by individuals, groups, families or cooperatives with minimal or no mechanisation, often in the informal (illegal) sector of the market’.1Hentschel, Thomas; Hruschka, Felix; and Priester, Micheal (2003) Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining: Challenges and Opportunities, London: International Institute for Environment and Development, Available at: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/9268IIED.pdf [Date accessed: 5 September 2024], p. 5. A distinction can, however, be made between artisanal mining and small-scale mining. Artisanal and small-scale miners rely on basic tools and limited technology to mine gemstones and key minerals and metals such as gold, cobalt, tin, tungsten, and tantalum.2]PACT (nd) ‘Artisanal and small scale mining’, Available at: https://www.pactworld.org/our-expertise/mining [Date accessed: 9 January 2025]. These materials are vital to the global economy, supporting essential products such as computers, mobile phones, aircraft, medical devices, and rechargeable batteries.3]Ibid. A significant share of these metals is sourced through ASM. Driven by the steady demand for these goods, artisanal miners persist in their work, often facing dangerous and exploitative conditions, including child labour and other human rights violations.4]IIED (n.d), ‘Chapter 13: Artisanal and small scale mining’, Available at: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/G00905.pdf [Date accessed: 9 January 2025]. Due to limited resources, ASM activities are usually confined to surface and shallow underground mining, representing the simpler side of small-scale mining.5]Minerals Council South Africa (n.d) ‘Artisanal and small scale mining’, Available at: https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/ [Date accessed: 9 January 2025]. Historically, ASM is a traditional practice with roots stretching back centuries across various cultures. Since ancient times, artisanal mining has been a core economic activity, supplying materials for adornments, tools, and construction, and was the dominant form of mining until the Industrial Revolution.6PACT, and ARM (2018) ‘The Impact of Small-Scale Mining Operations on Economies and Livelihoods in Low- to Middle-Income Countries’ Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a3929b640f0b649cfaf86ce/Pact__DFID_EARF_Overarching_Synthesis_Jan2018VF.pdf [Date accessed: 9 January 2025].

In Africa, artisanal mining is particularly prevalent, contributing significantly to local economies and livelihoods. The livelihoods of 130 to 270 million people globally depend on artisanal mining.7Girard, Victoire; Molina-Millán, Teresa; and Guillaume, Vic (2024) ‘Artisanal mining in Africa’, Nova School of Business and Economics, Working Paper No. 2201, Available at: https://novafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2201.pdf [Date accessed: 3 August 2024]. Today, artisanal mining is a highly controversial activity. To some, it is dirty and dangerous, disturbing and destructive, and frequently on the wrong side of the law. To others, it is profitable, productive, and the only means of survival in an environment with few alternatives. In Zimbabwe, artisanal mining plays a vital role in the informal economy, offering jobs to thousands of people amid widespread unemployment. While the sector operates with minimal regulation, resulting in environmental harm and safety concerns, it remains an essential source of income for families facing economic challenges.

This paper explores the complex narrative of artisanal mining in Africa, with a specific focus on Zimbabwe. It examines the prevalence and impact of artisanal mining, highlighting both its positive contributions and its negative consequences, including the rise of violent gangs known as ‘maShurugwi.’

Prevalence of Artisanal Mining in Africa

Artisanal mining is widespread throughout Africa, involving millions of people across the continent. Research indicates that over eight million people in sub-Saharan Africa work directly in ASM, with more than 45 million relying on these miners for their livelihoods.8]Hilson, Gavin (2016) ‘Farming, small-scale mining and rural livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa: A critical overview’, The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(2), 547-563, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.02.003 In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), artisanal miners contribute around 20% of the country’s cobalt output, which is essential for global industries like electronics.9Amnesty International (2016) ‘This is what we die for: Human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo power the global trade in cobalt’, Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/AFR6231832016ENGLISH.pdf [Date accessed: 8 January 2025]. In Zimbabwe, the sector plays a significant role in the economy’s overall development, accounting for over 60% of export revenues, more than 13% of gross domestic product (GDP), and attracting substantial direct investment into the country.10Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (February 2021) ‘Harnessing Technological evolution in the ASM sector for increased productivity and sustainability’ Available at: https://zela.org/harnessing-technological-evolution-in-the-asm-sector-for-increased-productivity-and-sustainability/ [Date accessed: 9 January 2025].

Similarly, in Ghana, ASM is a significant economic driver, especially for gold production, employing about one million people and supporting 4.5 million dependents, accounting for around 30% of the nation’s gold output.11Ibid. Formalising the sector could enhance sustainability and financial access for miners. Tanzania also relies on ASM, with small-scale miners contributing about 30% of its gold revenue.12The Chanzo Initiative (2022) ‘Here is Why Small-Scale Miners are the Future of the Tanzania’s Mining Sector’, 30 December, Available at: https://thechanzo.com/2022/12/30/here-is-why-small-scale-miners-are-the-future-of-tanzanias-mining-sector/ [Date accessed: 8 January 2025]. The sector fosters local economic growth by supporting businesses in mining-related services and infrastructure. In South Africa, ASM is expanding, particularly in high-value resources like gold, becoming an important income source amid high poverty and unemployment rates.13Ledwaba, P.F (2017). The status of artisanal and small-scale mining sector in South Africa: tracking progress. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy, 117(1), 33-40. Available at: https://scielo.org.za/pdf/jsaimm/v117n1/10.pdf [Date accessed: 8 January 2025]. These countries’ reliance on ASM highlights its role in rural development, though the sector faces persistent challenges, such as environmental degradation and the need for formalisation.

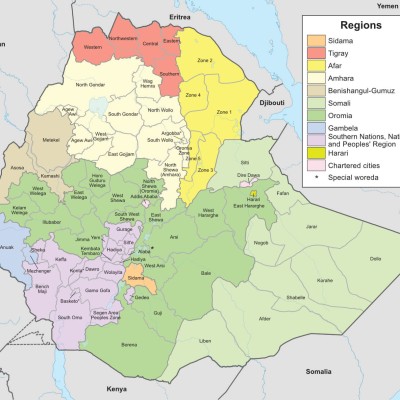

Artisanal Mining in Zimbabwe

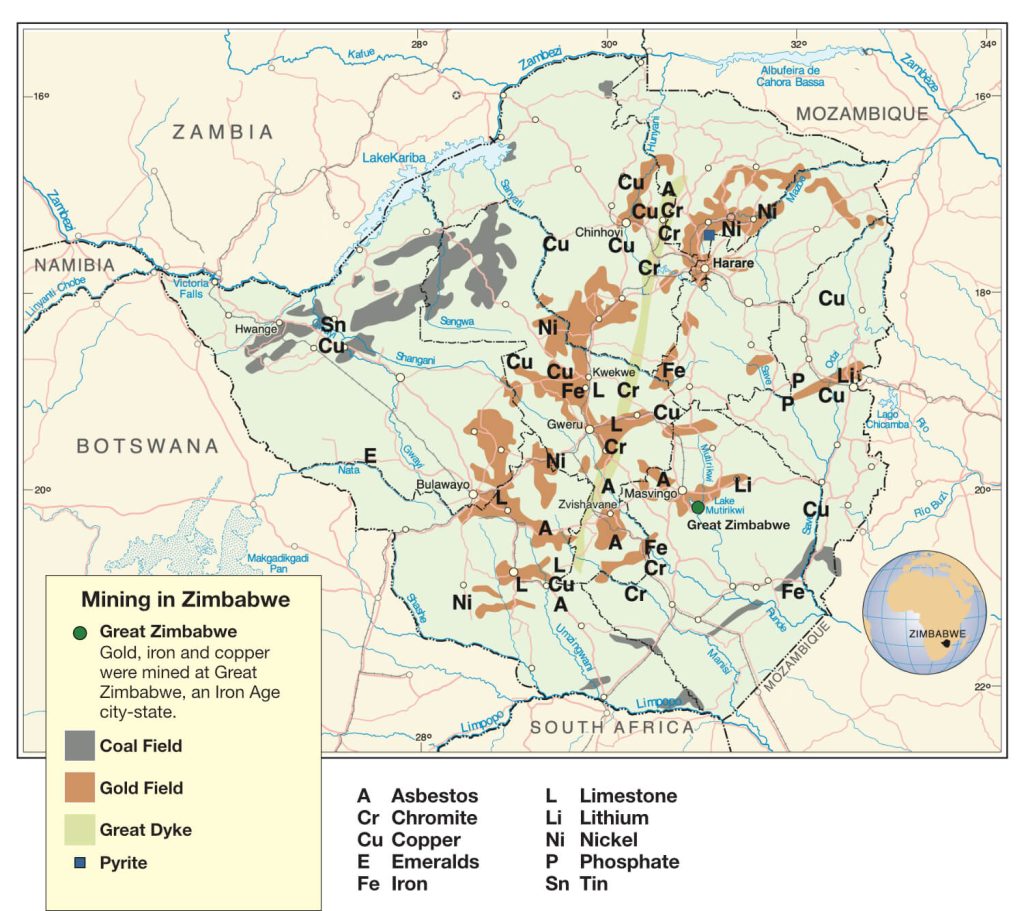

Artisanal mining in Zimbabwe has deep historical roots, with its practice stretching back to the pre-colonial period when local communities engaged in small-scale mining for gold, copper, and iron.14Pact Institute (2015) A golden opportunity: Scoping study of artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Zimbabwe, Available at: https://www.delvedatabase.org/uploads/resources/A-Golden-Opportunity-Opportunity-Scoping-Study-of-Artisanal-Scoping-Study-of-Artisanal-and-Small-Scale-Gold-Mining-in-Zimbabwe_190830_114528.pdf [Date accessed: 25 September 2024]. Over the years, the sector has adapted to changing socio-political and economic dynamics in the country. Today, artisanal miners, often called ‘makorokoza,’ play an essential role in Zimbabwe’s gold mining industry, contributing significantly to national gold production. This sector offers critical employment opportunities, particularly in rural areas where formal jobs are scarce, and it supports the economy through gold exports and local economic activity.

However, artisanal mining in Zimbabwe also brings challenges, including severe environmental pollution from mercury and other hazardous chemicals used in gold extraction. Miners face multiple health risks from toxic exposure and unsafe working conditions. Additionally, artisanal mining has been linked to violent groups known as maShurugwi. However, it is important to recognise that maShurugwi is often a pejorative term broadly applied to artisanal miners, reinforcing negative stereotypes and stigma.15Mkodzongi, Grasian (2020) ‘The rise of ‘Mashurugwi’ machete gangs and violent conflicts in Zimbabwe’s artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector’, The Extractive Industries and Society, 7(4), 1480-1489, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2020.10.001

The Rise of MaShurugwi

The term maShurugwi refers to groups of artisanal miners, particularly those involved in gold mining, originating in the Midlands towns of Shurugwi and Zvishavane, where they initially asserted control over illegal mining operations through violent means.16The Sunday Mail (2018) ‘MaShurugwi wreaks havoc’, 28 April, Available at: https://www.sundaymail.co.zw/mashurugwi-wreaks-havoc [Date accessed: 25 September 2024]. Over time, they extended their influence to other regions across Zimbabwe, expanding their dominance in unauthorised mining activities. This label is often associated with violent gangs who engage in unauthorised and frequently illegal mining practices. These groups have become a focal point of controversy and public concern due to the unregulated nature of their mining activities and the social issues surrounding them.

Figure 1: Map of Zimbabwe showing mineral deposits

MaShurugwi have developed a notorious reputation for violence nationwide, regularly intimidating other illegal miners through brutal tactics, including shooting, stabbing, and stoning anyone who resists them. Often armed with weapons such as guns, spears, knobkerries, and machetes, many of them are wanted by the police for allegedly committing serious crimes, including rape, kidnapping, and murder.

Negative Impact of MaShurugwi on Communities

MaShurugwi gangs have gained infamy for their brutal tactics and criminal behaviour. Their rise can be linked to economic hardships, high unemployment rates, and the profitability of gold mining. These gangs employ extreme violence to seize control of mining areas, intimidate local populations, and eliminate rivals. Their criminal activities include robbery, extortion, and murder, and they often engage in violent confrontations with competing groups, law enforcement, and formal mining companies over access to resources.17]Mkodzongi, Grasian (2020) ‘The rise of ‘Mashurugwi’ machete gangs’, op. cit. In gold-rich areas such as Kadoma and Kwekwe, they have been involved in violent clashes with local miners and residents, resulting in fatalities and widespread fear.

Similar conflicts have erupted in other gold-producing areas, further disturbing social and economic life. As a result, maShurugwi gangs have fostered an environment of fear and instability in mining regions. Their violent actions have led to numerous deaths and injuries, while their presence disrupts local communities, causing social breakdowns and economic instability.

Additionally, their illegal mining operations contribute to severe environmental damage, affecting local ecosystems and communities. Political connections and patronage have allegedly allowed maShurugwi gangs to operate with impunity.18Makichi, Tinashe (2022) ‘Powerful political and security interests manipulate mining law’, The Zimbabwe Independent, 23 December, Available at: https://www.newsday.co.zw/theindependent/opinion/article/200005372/powerful-political-and-security-interests-manipulate-mining-law [Date accessed: 25 September 2024].

Government Response to MaShurugwi

The Zimbabwean government has implemented several measures in response to maShurugwi gangs, though their effectiveness and consistency have varied:

- Enhanced security measures: The government has deployed police and military forces to areas affected by maShurugwi gangs, conducting raids and increasing patrols to curb violence and restore order.19The Herald (2020) ‘Parly, police up fight against machete gangs’, 9 January, Available at: https://www.herald.co.zw/parly-police-up-fight-against-machete-gangs/ [Date accessed: 9 January 2025].

- Legal action: Law enforcement has arrested and prosecuted maShurugwi members for crimes such as robbery, assault, and murder.20Ibid However, challenges persist due to the gangs’ influence and the informal nature of mining activities.21International Crisis Group (2020) ‘All That Glitters is Not Gold: Turmoil in Zimbabwe’s Mining Sector’, 24 November, Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/southern-africa/zimbabwe/294-all-glitters-not-gold-turmoil-zimbabwes-mining-sector [Date accessed: 9 January 2025]

- Regulation and licensing: Efforts to regulate artisanal mining have been stepped up, with initiatives such as issuing licenses and implementing stricter controls on mining operations. The goal is to formalise the sector and reduce illegal mining that often involves maShurugwi gangs.22Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit (2018) ‘Pathway to formalization of artisanal mining’, Available at: http://artisanalmining.org/InventoryData/lib/exe/fetch.php/biblio:zwe-2018a.pdf?cache\= [Date accessed: 9 January 2025]

- Community engagement: The government has also engaged with local communities to tackle the root causes of violence, promoting economic opportunities and alternatives to illegal mining. A key initiative in this effort is the training offered by the Zimbabwe School of Mines, which focuses on the fundamentals of mining management. This capacity-building programme has proven transformative, equipping individuals with essential skills and enabling a significant number of young miners to transition from informal and artisanal mining practices to more formalised and well-structured small-scale mining enterprises.23Chronicle (2023) ‘Miners capacity-building program a game changer’, 26 January, Available at: https://www.chronicle.co.zw/miners-capacity-building-program-a-game-changer/ [Date accessed: 9 January 2025]

- Anti-crime campaigns: Various anti-crime initiatives, such as Operation Chikorokoza Ngachipere (“No more Illegal Mining”),24Mining Zimbabwe (2021) ‘Over 25000 arrested under operation Chikorokoza Ngachipere’, 28 July, Available at: https://miningzimbabwe.com/over-25000-arrested-under-operation-chikorokoza-ngachipere/ [Date accessed: 9 January 2025] have been launched to combat illegal mining and organised crime, aimed at dismantling criminal networks and lessening their impact on local communities.

In 2020, the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) ramped up efforts to combat the gangs, leading to many arrests. In January of that year, the ZRP had apprehended 369 individuals involved in illegal mining and associated crimes.25]The Zimbabwe Mail (2020) ‘Police says it has disarmed most MaShurugwi terrorists’, 15 January, Available at: https://www.thezimbabwemail.com/law-crime/police-says-it-has-disarmed-most-mashurugwi-terrorists [Date accessed: 4 October 2024]. Furthermore, the government set up specialised courts to accelerate the prosecution of maShurugwi members in an effort to address the violence swiftly. However, despite these initiatives, significant challenges remain due to the entrenched nature of ASM and the financial motivations behind illegal mining.

Economic and Social Benefits and Drawbacks of Artisanal Mining

Artisanal mining offers both significant economic and social benefits as well as notable drawbacks. On the positive side, it provides direct employment to millions of people, particularly in rural areas where formal job opportunities are scarce.26World Bank (2020) ‘State of the Artisanal and Small Scale Mining Sector’, Available at: https://www.delvedatabase.org/uploads/resources/Delve-2020-State-of-the-Sector-Report-0504.pdf [Date accessed: 9 January 2025] It encourages entrepreneurship, fostering self-reliance and economic activity. Revenue from artisanal mining plays a vital role in driving local economic activities. It creates backward and forward linkages, such as the supply of tools, equipment, and services, alongside mineral processing, which benefits local businesses. In some countries, earnings from artisanal mining are sometimes used to fund development projects such as schools, healthcare centres, and infrastructure, directly enhancing living standards in mining communities.

In Tanzania, the ASM sector plays a crucial role in the economy by generating substantial revenue through taxes and royalties.27Njonde, Cyrus (2024) ‘Tanzania’s artisanal mining renaissance and its key enablers’, African Mining, 1 August, Available at: https://www.africanmining.co.za/2024/08/01/tanzanias-artisanal-mining-renaissance-and-its-key-enablers [Date accessed: 20 November 2024] These earnings have been invested in infrastructure development, particularly in the establishment of mineral processing centres such as the Katente and Itumbi stations. The development of these centres has not only enhanced the gold refining process but also contributed to the growth of local economies by providing jobs and supporting small businesses.28Willison Mutagwaba, John Bosco Tindyebwa, Veronica Makanta, Delphinus Kaballega and Graham Maeda, ‘Artisanal and small-scale mining in Tanzania – Evidence to inform an ‘action dialogue’’ Available at: https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/16641IIED.pdf [Date accesssed: 9 January 2025] In Ghana, although the government has faced challenges in fully formalising artisanal mining, there are instances where the income generated by miners is reinvested into the local economy.

Artisanal miners typically use their earnings to purchase assets or support local businesses, indirectly contributing to community development and infrastructure.29Ghana Minerals Commission (2020) Minerals Commission 2019 Annual Report, Available at: https://www.mincom.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2019-MINCOM-ANNUAL-REPORT.pdf [Date accessed: 20 November 2024]. Initiatives such as the Mineral Development Fund aim to direct mining revenues into projects that benefit local communities affected by mining activities, enhancing economic growth and sustainability.30Profile of MDF, Available at: https://www.mdf.gov.gh/profile-of-mdf/ [Date accessed: 9 January 2025] Additionally, in many countries, artisanal mining plays a key role in national economies by boosting mineral production and export revenues, particularly in sectors like gold and gemstones. However, the sector also poses serious challenges.

Environmental degradation is a major concern, with deforestation, soil erosion, and water pollution caused by the use of hazardous chemicals like mercury. Large forested areas are cleared to access minerals, destroying habitats and reducing biodiversity. Deforestation contributes to climate change by diminishing natural carbon sequestration. Soil erosion is another critical consequence resulting from vegetation removal, which destabilises land and strips it of fertile topsoil. This degradation compromises agricultural productivity, threatening food security for farming-dependent communities. The use of toxic chemicals, such as mercury and cyanide, in gold extraction exacerbates environmental harm. These substances frequently contaminate rivers and groundwater, posing risks to aquatic ecosystems and human health. Mercury, which accumulates in fish, introduces toxic elements into the food chain, leading to severe health issues, such as neurological damage.31World Health Organization (2024) ‘Mercury’, 24 October, Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mercury-and-health [Date accessed: 22 November 2024]. Abandoned mining sites often become hazards, with stagnant water in pits providing breeding grounds for mosquitoes and increasing the risk of diseases like malaria.

The lack of proper equipment, such as helmets, gloves, and masks, safety protocols and training in safe mining techniques leads to frequent accidents, resulting in health issues for miners. In January 2024, a shaft collapsed at an artisanal gold mine in Mali’s Koulikoro region, killing more than 70 people.32Al Jazeera (2024) ‘More than 70 dead in artisanal mine collapse in Mali’, 24 January, Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/1/24/more-than-70-dead-in-artisanal-mine-collapse-in-mali [Date accessed: 25 September 2024]. Harsh working conditions, marked by extreme heat, insufficient ventilation, and inadequate access to clean water and sanitation, heighten risks of dehydration, heat-related illnesses, and waterborne diseases. Women and children, who are often involved in mining activities, face distinct dangers, such as physical exhaustion and exposure to chemicals that may affect reproductive health. Women in mining areas are also particularly at risk of gender-based violence, harassment, and exploitation, challenges that are exacerbated in unregulated and informal mining settings. While they make up a significant portion of the workforce, their contributions are often relegated to roles that are physically demanding and less profitable,33US Agency for International Development (USAID) (2020) ‘Gender issues in the artisanal and small-scale mining sector’, LandLinks, May, Available at: https://www.land-links.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/USAID-ASM-and-Gender-Brief-1-June-20-Final.pdf [Date accessed: 22 November 2024]. such as carrying ore, processing minerals, or managing tailings. These positions typically pay less than the higher-paying roles, such as digging or supervisory tasks, which are predominantly held by men.

The informal nature of artisanal mining makes it difficult to regulate, contributing to issues such as tax evasion and illegal trade, as miners operate outside the scope of official taxation systems.34Ivanov, Boris (2024) ‘How to clean up artisanal mining’, Mine, 147, December, Available at: https://mine.nridigital.com/mine_dec24/how-to-clean-up-artisanal-mining [Date accessed: 18 September 2024]. Informal mining practices facilitate the illegal trade of minerals, which undermines national economies and fosters an environment where exploitation and poor working conditions persist. The lack of formal agreements or documentation weakens the enforcement of labour laws, contributing to challenges such as child labour and unfair wages.

In some regions, artisanal mining is linked to conflict, violence, and the financing of armed groups, exacerbating social instability. In the eastern DRC, artisanal mining operations involving minerals such as tin, tungsten, and tantalum are a key funding source for armed groups. Militias control many of these mining sites, profiting from the trade of these valuable minerals, often referred to as ‘conflict minerals.’35US Government Accountability Office (2024) Conflict Minerals: Peace and Security in Democratic Republic of the Congo Have Not Improved with SEC Disclosure Rule, Congressional Committee report, October, Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-25-107018.pdf [Date accessed: 6 September 2024]. This control enables armed groups to extort miners, leading to ongoing violence and instability, and significantly prolonging conflict in the region.

Conclusion

Despite their informal status, maShurugwi play a central role in Zimbabwe’s gold mining industry, contributing a considerable share of the country’s gold production. Operating primarily in impoverished and marginalised areas, their activities bring mixed social effects. On the one hand, they create jobs and generate income; on the other hand, they contribute to environmental damage, displacement, and incidents of violence. Concerns have been raised over human rights abuses linked to their operations, including excessive force by law enforcement and violence against civilians. In Zimbabwe, artisanal mining is a critical economic lifeline but comes with risks heightened by the violent actions of maShurugwi gangs. Addressing these issues calls for a multifaceted approach – one that involves regulation, community involvement, and alternative economic pathways to harness the benefits of artisanal mining while minimising its negative impacts.

Artisanal mining across Africa is a complex landscape, offering significant economic benefits, but also posing serious social, environmental, and health challenges. Despite the many challenges, adopting sustainable practices and enforcing stricter environmental regulations could mitigate many negative effects, promoting a balance between economic benefits and environmental stewardship. Collaborative interventions involving governments, nongovernmental organisations, and private entities are also essential to provide affordable safety equipment, specialised training, and healthcare support to mitigate health risks.